January 23, 2017

CR Holiday Interview #7—Joe Casey

CR Holiday Interview #7—Joe Casey

*****

I'd like to thank the endlessly patient

Joe Casey for the amount of time he's waited to see this interview come out. I hope that a mid-week placement, the last in this year's abortive Holiday series, and the piece's afterlife will make up for my delay.

Casey is the comics professional I've interviewed most for publication, and is right up there with people like

Seth in terms of cartoonists I've talked to for people to read and for people to see at shows. Like most of my favorite comics-makers, Casey creates I think in great part out of an abiding love for seeing his work make its way into the world. He may play it off better than most, but I still feel that thrill is there. Casey works quickly enough and at a high enough volume there's an unspoken weight provided recurring subjects, a hangover of comics' commercial roots that's one of my favorite things about the medium. Casey is cognizant of comics history and holds himself to high standards he's fashioned from the works he admires most.

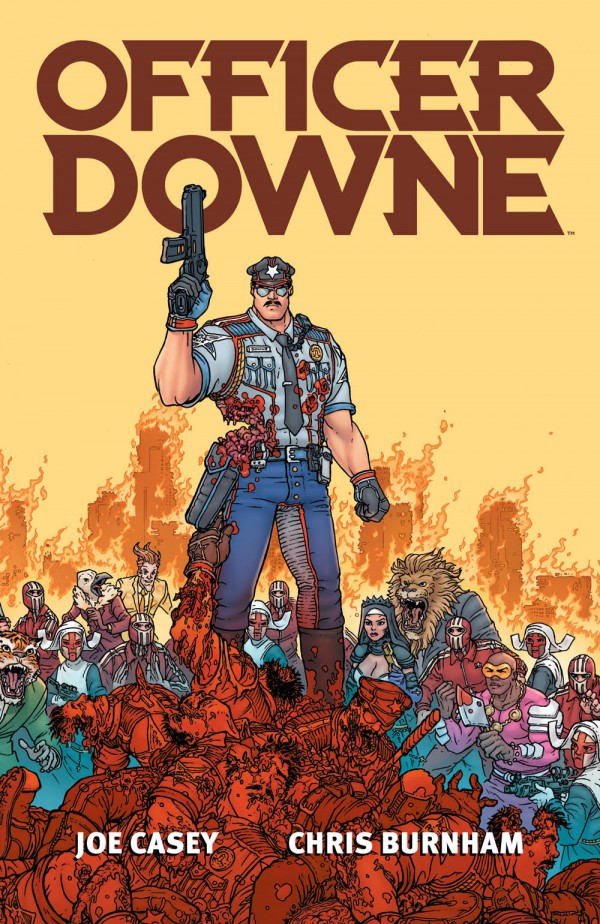

Casey had an interesting 2016, climaxing near year's end with the premiere of a movie based on his hyper-violent satirical work with

Chris Burnham,

Officer Downe. There's a new book version of the comic series just out; I enjoyed reading that comic and like a lot of the comics I enjoy most I find Casey's work just enough removed from what he's engaging to preserve its role as commentary without becoming arch or clinical.

Casey's comic with

Piotr Kowalski,

SEX, drips with menacing languor and is idiosyncratic to the creators' concerns in a way I wish every collaborative comic could be.

I always enjoy batting things around with Joe and admire his searching, seeking manner. I tweaked for flow. -- Tom Spurgeon

*****

TOM SPURGEON: So place me into what exactly you have going on right now with this movie. This is not just your property, but you were fully involved, like Daniel Clowes on his various sets. Can you give us an explicit idea of what your involvement encompassed and how it developed?

JOE CASEY: As weird as it is to say -- because I'm such a fan of his work -- I might've gone a step further than Clowes has on his films. While he's obviously worked on the screenplays of his adaptations, I'm not sure if he's ever been a full-blown

producer, where he was on set each and every day and was balls deep in every step of the process.

When the other producers approached me about the feature rights for the book, they had nothing. They had no money, nothing more than a vague plan of how to make it happen. And, of course, they had a certain enthusiasm that I obviously responded to. But we really started from square one. So I was there for all of it... from writing the screenplay to pitching to financiers to casting to pre-production to principal photography to editing to approving VFX to sound mixing to talking to distributors. And now we've been marketing the release. We'll do it again with the Blu-Ray release in February.

I've said this before, but it's very much been the "Image Comics" approach to filmmaking, where I've been responsible during every stage of the process. And, to be clear, it wasn't by happenstance... I

wanted the experience to be all-immersive. There was really no point in doing it if it wasn't going to be something of a life changer for me and my creative life.

SPURGEON: Do you feel like you're a natural movie guy, that you have stuff to say as a creative person through that medium? You've certainly worked in a way that's directed towards animation. But is there a comics-element to the way you're involved? That's not always a clean transition.

SPURGEON: Do you feel like you're a natural movie guy, that you have stuff to say as a creative person through that medium? You've certainly worked in a way that's directed towards animation. But is there a comics-element to the way you're involved? That's not always a clean transition.

CASEY: You never really know how comfortable something's going to be until you dive in and do it. For me, I'm an inveterate process junkie... but that doesn't just apply to comic books. It applies to music. It applies to cinema, too. So I had a pretty good idea going in what the gig entailed and how I might exist creatively in that space. Turns out my relentless, compulsive need for control works fairly well in the realm of filmmaking. At the same time, there was definitely a learning curve, but I was ready for that, too. Besides... clean transitions have never been something I've been particularly concerned with. I figure messy is always better. It's certainly more interesting.

SPURGEON: Can you give a specific example of something that was maybe a bit steeper than normal on the learning curve? What was messy? What was hardest for you?

CASEY: Well, I'd produced and directed another movie before, but this was on a much larger scale. So it's not like there was any one specific thing that was difficult... it was simply the

amount of stuff to keep track of. Being so near the top of the creative food chain on this thing, it was part of my responsibility to make sure everything got covered, that no details were lost in the chaos. And I think I did a decent job of it, but there were inevitably things that were happening on set that I simply couldn't be a part of.

Part of the filmmaking process -- a big part, in fact -- is trying to prevent circumstances that'll bite you in the ass later. Making sure you don't make mistakes in the heat of the moment that'll end up costing you down the line. For instance, getting enough coverage in a scene to be able to edit it into something later. If you don't have enough footage, enough choices, to build a good scene in the editing room, you're fucked and there's nothing you can do about it except get rid of the scene altogether. So it was the amount of concentration required that really impressed me.

SPURGEON: Are you comfortable describing this work as satire? Is that a mantle you find interesting or useful in your work more generally?

SPURGEON: Are you comfortable describing this work as satire? Is that a mantle you find interesting or useful in your work more generally?

CASEY: As you well know, my formative years were the 1980's, when comic books -- even superhero comic books -- were at their most satirical. A lot of my favorite creators at that time --

Moore,

Miller,

Chaykin and others -- were often satirists as well as storytellers. Or, at the very least, satire was always an element in their work. So I feel like it's part of my DNA. That, and a punk rock sensibility mixed with a measurable disdain for authority that I'm sure has undercut the level of

intelligent satire I'm capable of.

SPURGEON: [laughs] How do you mean?

CASEY: I feel like my heroes used satire with a surgeon's precision. I use it more like a bludgeon, much more ham-fisted about it. In other words, the kind of satire that shows up in my work is more of an absurdist laugh rather than biting political commentary. I think

Officer Downe -- the comic book -- proves that. It's definitely not subtle. Having said that, I'm not sure if I would describe the film version as much of a satire. I think the roller coaster ride aspects of it overshadow just about everything else. That was the idea, anyway.

SPURGEON: What is the value, then, do you think, of that approach, that howl, that kind of massive shove back that isn't precise? It seems to me there was a time when satire like that had a role in calling attention to things right in front of our faces, but we're all a bit more weary and cynical now. Is it a call to forego complacency? Is it that you get a range of effect by working at the volume of 11 that you don't get with a laser-focused approach?

CASEY: Y'know... it's about getting off your lazy ass and putting a shit-ton of distortion on your guitar and cranking it through a Marshall stack while screaming through a million-watt PA system... as opposed to simply strumming an acoustic and humming a folkie protest song. It's "Like A Rolling Stone" as opposed to "Blowin' In the Wind." It's a garage band aesthetic, all the way. Arena cock rock over quiet coffeehouse gigs. Speak sharply and carry a sledgehammer, right?

For me, it's an approach that feels the most comfortable. It's

how I deal with the weariness and cynicism -- both in the world and within myself. That "howl," as you refer to it... it's what the world feels like to me. Or maybe what I

want it to feel like. The thing is, as strange as this'll probably come across in a printed interview, I'm not trying to educate anyone or illuminate anything for anyone other than myself. I suppose I save any of my "laser-focused" approaches for things much more personal, not necessarily meant for public consumption.

SPURGEON: Do you worry about people not getting it, that whole "No, we see Rorschach as wholly admirable" trap where there's a disconnect between intent and the audience's appraisal of what's going on? Is there a fine line between getting a high-five from people who won't take that step with you but also making the object of your parody a legitimate expression of what you want to explore so that you can make the comment you'd like to make? Does it have to feel real for you to introduce a level of commentary?

CASEY: It feels like it's been a long time since I gave a shit about anyone "getting it." [Spurgeon laughs] So long, in fact, that it's tough to remember when I actually did. And, by having that attitude, I know I run the risk of missing out on certain connections that I'm sure other creators make with their readers. Anything that operates on a purely subtextual level in my work wouldn't be something that I would ever expect a reader to get. Again, those things are in there mainly for my own amusement. Even when the commentary runs deep, it's still personal to me and I have no expectations that anyone else is onboard. So, in terms of "fine lines..." there are none. Not for me, anyway.

But I'm okay with that. As you know me, I'm a guy that's not on any social networks, either. I prefer that distance, I guess. I think, in comic books especially, it's about the Art and not the Artist. And, listen, a high-five from someone over a piece of work you've done is nothing to sneeze at. A high-five is a perfectly acceptable critique. Even laudable.

SPURGEON: In general, then, do you think people always understand where you're coming from? You work in some unique spaces in terms of hard expectations and a sometimes-rigid genre structure or even specific storytelling demands. Do you recall an instance in your career when you felt you were understood and appreciated for exactly what it is you sent out to do? Is there a story that stands out, or a work that stands out where you felt it kind of slipped that appreciation?

CASEY: A lot of the work I've done that I've been most proud of hasn't been popular by any measurable -- or, to be more specific, commercial -- standards. Now, I'm painfully aware that this is a First World Problem of the most annoying-sounding kind. But you asked.

SPURGEON: I did.

CASEY:

CASEY: In the creator-owned area, there's things like

GØDLAND or

Butcher Baker the Righteous Maker or

The Bounce, where I felt like, for me, I'd moved the needle a little bit, in terms of using genre to make a personal artistic statement. And even in the WFH space, things like the

Captain Victory book I did -- with a host of all-star artists -- or the

Catalyst Comix series at Dark Horse. Same with the

Vengeance series I did at Marvel with Nick Dragotta and the

Zodiac book I did there with Nathan Fox. Those things were aesthetic creative victories for me that I would never take for granted.

But that's how it goes sometimes. Hell, these days you could probably find a handful of random readers who'll admit to having fond memories of my run on

Uncanny X-Men, which was pretty much universally reviled when it was coming out 15 years ago. Same with my last year -- the "pacifist" year -- on

Adventures of Superman. Same with my

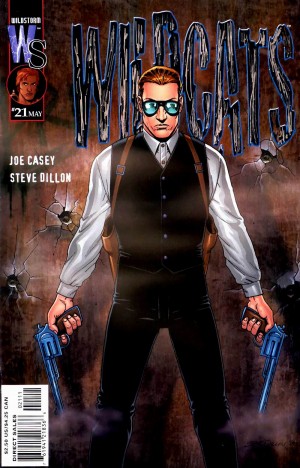

Wildcats run and especially

Automatic Kafka... books that some people now hold up specifically as high points in my career. But, y'know, I suppose I prefer that cult-level, artistic resonance over being a flash in the pan that hits big and is then completely forgotten. There's a lot of that in comic books, especially in the last 30 years.

SPURGEON: Did the election change the context for Officer Downe

?

CASEY: My knee jerk response to that question is, "God, I hope not," because I think that Entertainment -- and that's a separate thing from Art, by the way -- should remain as Entertainment no matter what the political climate. Is that shallow? Maybe so. But popcorn should taste the same no matter who's running the world. And

Officer Downe -- the book

or the film -- certainly isn't out to make any kind of heavy social statement. It's pure pulp pop and it's not meant to be anything more. I'm pretty sure the concept can't

carry anything more than that.

These days I feel like being able to genuinely tap into any kind of wider cultural zeitgeist is not a big part of my skill set. It might happen by accident on the rare occasion, but I'm not convinced that I have the talent to ever purposefully

make it happen.

SPURGEON: I wanted to ask a question about

SPURGEON: I wanted to ask a question about SEX

, which is a comic I enjoy a lot. The conventional wisdom amongst my friends that read it is that it's about 1980s world-building, which is something that's been discussed in terms of that work. But I wonder if what's really going on is if by recognizing the sexual nature of motivation you're forced into world-building, the same way that Steve Englehart had to do it that during his Avengers run where he allowed the personal narratives happen in overlapping ways. Do you have to create a world that encompasses the themes you're addressing?

CASEY: Okay... let me see if I can talk about this without bursting anyone's bubble. The "world-building" aspect of a lot of things I do involves a lot of improvisation. I'm a character-first kind of writer. And the rest of it all flows from character. Saturn City without Simon Cooke -- or Keenan Wade or anyone else who lives there -- is a pretty empty place. Character motives are everything. When you separate it from the obvious meta-commentary, the actual narrative is not so much about themes, I don't think. It's about behaviors. That's what I'm interested in depicting in the series. How do these characters react when thrust into certain situations, primarily situations they're not particularly built for? Taking characters out of their comfort zones is always fun to write. And, as I go along, I guess I do create the world -- or I'm "forced" to, as you suggest -- in order to contain those ideas, hopefully in an interesting manner. But it's to support a conceit more than it encompasses a theme.

Maybe I'm splitting hairs there. I just don't want to take too much credit for something that I know I'm not putting a great deal of effort towards. If

SEX has a theme, it's a pretty simple one: It's Time To Grow Up. The rest is window dressing.

SPURGEON: One thing I think is funny about SEX

is that once you add in these personal elements it makes the lives of your characters seem crowded, like if you're doing real-person stuff where the hell do people find time to do this kind of costumed crimefighting which informs what they're up to now. Do you feel as harried as the characters in that book? Do you feel time slipping away, professionally and personally?

CASEY: Jeezus... I do feel that. I feel it more and more, lately. That's probably why it's such a part of the series. I've been going at this full-on for twenty years now. My relationship to my work is the longest committed relationship I've ever had and probably will ever have. The only relationship that's gone on longer than that is my relationship with comic books themselves. That one's been going on at least twice as long...! So, yeah, I'm feeling the time passage.

I've always had a thing about mortality... how we're here now and at some point we'll be gone. But when I was younger it was nothing more than the neurosis of a high strung kid. Now it's more of a grim reality, staring me in the goddamn face, which is scary as fuck. And, of course, we've seen a lot of death in 2016. That never helps.

SPURGEON: That's a book with backmatter. You and maybe Ed [Brubaker] are the only people I know that do that effectively. John Porcellino, too. Does engaging in conversation about the culture of comics, the sweep of the art form, do you do that because you don't see it a lot of place? What do you think about the current state of our rhetoric about comics, how we discuss what we're reading and how we feel about it.

CASEY: It's ironic you bring that up, since I'm about to close down the

SEX letters page for the very reason you're implying. It's something I've possibly gotten adept enough at that I feel like there are times when it can overshadow the work, the comic book itself. And that's not how it's supposed to be. Granted, as a lifelong process junkie,

I'm certainly more interested in reading that type of analysis or discussion more than I am the actual

comics being discussed. And there are plenty of folks who do it a lot better than I ever will. You're one of them, Tom. But as far as being a

provider of that kind of entertainment as a profession, I think I have more of a responsibility to try and make good comics than I do to be able to talk about them intelligently.

SPURGEON: Can you tell me how as a working professional you've processed some of the deaths we've seen this year, or how you might do that generally. Is it solely personal or does part of you grieve the lost of the art, that specific avenue of expression that someone embodies. Has a comics industry passing ever hit you hard?

CASEY:

CASEY: I'm pretty sure I'm the kind of person who doesn't process death in general especially well. I tend to try and ignore it, really... mainly out of a fear that the sheer enormity of the concept will send me crawling back under my bedsheets, never to emerge. When creative people in particular leave us, you're suddenly adjusting to a new world, a world in which these people no longer exist. It can change you, often in subtle ways. But I've had close relatives die, so I know the difference very well.

Darwyn Cooke's passing came out of nowhere for me. I didn't know him personally at all, but he carried a particular torch that I think we needed in this industry, so there's a definite vacuum there. Steve Dillon, who I'm proud to say I worked with on two issues of

Wildcats, represented a certain artistic aesthetic to me, an approach to storytelling that was so singular and so... comfortable in its own skin. His art was like an old friend, and now that old friend is gone.

In my time as a professional, there have certainly been deaths that occurred over the years -- of people that I had a little more of a connection to -- that hit me in different ways. Ringo's death stunned me, because I'd worked with the guy and thought he was so good. But he had a certain personality that just seemed to me like he'd hang around to be a gloriously grouchy old man. There was Bill Oakley, a legendary letterer who worked on the first few years of my

Adventures of Superman run (with Ringo, coincidentally). Clément Sauvé, who was a fantastic artist I'd worked with a bit on some random superhero launch in the mid-2000's, was one who died way too young.

It's not that they hit me particularly hard... it's just a very confusing thing, all around. ComiC book creators are generally not the type of people that you predict will leave us so suddenly or so young. You think more of Kirby, who lived to a fairly ripe old age. Or Stan Lee, who may be ancient as fuck... but he's still out there kicking up dust.

SPURGEON: Do you ever regret working in a medium with such a utilitarian perspective on shared creative effort? Like you strike me as the kind of writer where younger creators will pick up on a specific element or two or eleven and then work those elements into their work. I know I've seen, for example, The Intimates waving at me from other people's comics, intentional or not. Does that annoy? Does that even register?

CASEY: It registers, because people occasionally point it out to me. I've seen it here and there, but y'know... I've worn

my various influences on my sleeve from time to time.

The Intimates came from somewhere, too. Its creative antecedents are

so obvious to me. But it's the Circle of Life, y'know? Maybe the difference is that I'm perfectly comfortable admitting it. I've never been embarrassed to say that a writer like David Michelinie was a big influence on me as a kid. Or Bob Fleming. Or Mike Baron. Or any number of comic book creators who weren't necessarily transcendent "superstars" at that Frank Miller/Alan Moore-level of rarified air, but who nonetheless hit me at the right time in my own development. They shaped my sensibilities in a very tangible way. They really meant something to me. The fact that they

weren't at the top of the charts just makes their influence that much more poignant for me.

So clearly I don't have that particular insecurity that keeps me from taking a certain pride in being a link in a longer creative chain. But I dunno... it could be that not everyone feels that way.

SPURGEON: Given the shifting realities of the industry, would it have been possible for you to have the same career were it to start right now? For instance, could you have been a creator that parlayed a big social media presence into opportunities? Could you have crowdfunded books?

CASEY: Not in a million years. That's just not me. For better or worse, I'm a product of my times. I grew up with the firm belief that the world didn't owe me a goddamn thing, that if you bet on yourself and were willing to work harder, push yourself further than the guy standing next to you... you could make it to that place you wanted to be. If anything, I would've published things online for free. Making comic books is practically a compulsion for me. I was doing it before I went pro so there's no scenario I could imagine where I'm

not doing it. I've spent the better part of my life learning this language, so to not speak it as often as possible seems ridiculous. Not to mention, I love doing it.

The "big social media presence" part of it all... that's a different subject altogether. I don't understand how someone could

have a big enough social media footprint without actually having

done anything to merit the attention. So to try and engineer one with the goal of getting paying work doesn't make a ton of sense to me. It wouldn't feel right. But I know people do it, I know it works for some people, both professionally and personally. I just know myself... I'd feel weird if I tried to do that. The equation for me has always seemed to be: Work First, Recognition Second. Never the other way around.

But who the hell knows? Maybe it

would be easier for me to break in now than it was when I actually did. I honestly haven't thought about it too much. I can tell you that in 1997 it was a million-to-one shot that I'd ever make a genuine run at being a professional comic book writer. And for Marvel and DC, to boot. To this day, I still look back and find it hard to believe it actually

worked out for me...! I was a Nobody from Nowhere with no formal training, no significant educational background to speak of, I'd never been to New York City... all of those things that, at the time, seemed to mean something to people. So, in many ways, the deck was stacked against me. And not only did it work out, it exceeded practically every dream I'd ever had when I was a kid about doing this for a living.

As you can tell... I've processed that just about as well as I have the concept of death...

SPURGEON: What do you feel about the state of the industry in general? A lot of people are happy with the opportunities they have, but I talk to a lot of comics professional that wonder what's in place to deliver their work to people who want to read, almost in foundational terms. Are you happy with the opportunities you have to place work in people's hands, to get work in front of folks' faces.

CASEY: I know there's a lot of nervousness right now about comic book retail stores closing. But haven't we

always been nervous about that sort of thing? There's always been the concern that this entire thing is built on quicksand. And maybe that's true. Maybe it is. But I know that comic books -- as a medium, as an art form -- are pretty goddamn resilient. They seem to survive, no matter

what the upheaval. So, based on history alone, I'm not particularly worried myself.

For me, and my own work, it's very simple: I want the work to

exist. That's my primary goal, that it's physically out there in the world. At this point in my career, it's the only thing I can completely control, y'know? Whether or not people read it or react to it, that's beyond me. My own satisfaction begins and often ends with knowing that something I've done is out and available for anyone who ends up finding it, picking it up, buying it, etc. So

creating it is the first priority. It's where I feel I should expend the most energy.

Having said that, I do recognize that it's an ever-shifting landscape. You have to be adaptable to the way it ebbs and flows. In my creator-owned work (my Image comics, basically), I'll be trying different formats for different projects, more diverse methods of delivering the material that might better match the current state of the Direct Market. I'm not talking about reinventing the wheel or anything groundbreaking like that... I'm just going to be more responsive instead of bullheaded when it comes to putting out product. It's really another avenue for creativity. That's how I choose to look at it, anyway...

SPURGEON: Now that we know comics can be for everybody, something for which people fought on a significant number of fronts by several players of different kinds in comics, what's the next battle for comics? What's the thing you'd like most to see go away or being put into place? For that matter, do you even think in terms like that anymore, and do you feel like comics pros have a responsibility to other creators?

CASEY: I'm not sure who's responsible for what anymore. The big publishers have become nothing less than Hollywood studios, both in theory and in practice. And that's kind of a shame. Then again, those kind of large corporate structures -- not just in the comic book industry -- are still a very closed system. They're still rife with all the problems, the social ills and prejudices they've always seemed to contain. So, I guess we can say that the comic book industry has, in many ways, caught up with the rest of the entertainment business. Hooray for us.

But, let's not forget, we

wanted this. All of this nonsense was our dream for the industry. We

wanted to be on the same level as the rest of pop culture. To be "taken seriously." I know, for myself, I relished the challenge of whether or not we could maintain our integrity -- as an artistic medium -- in the harsh light of "Hollywood" culture,

Entertainment Weekly and the endless levels of exploitation that comes along with it. Turns out, those forces were much more powerful than we could ever hope to be. We stepped right up to be exploited. Or we bent over, if that's the way you want to look at it.

The industry itself -- long before this shift -- has always suffered from the three "I's": Insensitivity, Ignorance and Ineptitude. It's suffered from an incredible

abundance of all three, actually. There's generally no real evil or malice involved. But those three things can still do a lot of damage... and have. So we've still got a lot of things to overcome, a lot of history to account for. A lot of bodies left bleeding in the street.

I think I just want even better comics. I want works of Art that are motherfucking

transcendent. And I target that desire squarely at myself, too. So it's a personal battle, as well as a hope for the industry. I still want to believe that if the quality of the work is high enough, we can survive

any of the extraneous bullshit that comes with where we've all collectively found ourselves.

So after all that, lemme try to answer your question as definitively as I can: Maybe the next battle for comics is simply the eternal struggle not to destroy ourselves...

SPURGEON: Did you receive any blowback for your recent criticism of diversity hires at mainstream comics companies having a marketing element and being tied into specific characters rather than these being opportunities to secure high-profile gigs across the board? Are you ever frustrated with the way comics processes issues more generally? Is there anything that worries you that you'd love to see addressed that isn't being discussed?

CASEY: No blowback whatsoever. At least, none that I'm aware of. And if there was -- so what? I do think I've earned the right to comment on just about any aspect of this business that I care to. That doesn't mean anyone has to pay any attention. But I've been in it twenty years now... which, by the way, is about nineteen more than I ever expected to be. It's been my life for so long, I've got my opinions and if I'm asked, I'll share 'em. And, let's be honest,

everything is about marketing when it comes to corporate publishing. Because marketing translates into money. Of course, it's certainly distasteful when corporations exploit identity as a way to make money, but I'm never surprised when they do it. So it's not like I'm blowing the lid off some hidden scandal. Anyone who hasn't already realized this is happening is, in my humble opinion, slightly naive as to how the world works.

But I'm a creator, I'm fully on the Art side of things, so I don't

have to be sympathetic to corporate needs. I think I see a bigger picture. First of all, let's pretend we actually

care about big, corporate superhero publishers and the product they provide...

A talented black writer writing a black franchise superhero character is certainly going to be affecting, but quite honestly, I'm much more interested in that same black writer's take on a character like Superman or Thor or Captain America. If there's going to be a push for "diverse" creators in the field, the real push should be to get them working on non-stereotypical material. Now, granted, if those are the only jobs being offered to non-white, non-male, non-straight creators then if you want to work, you take the gig and you cash your check and more power to you. Nothing wrong with getting paid. This is not on the creators... this is on the publishers and their hiring practices.

So a good female creator writing

Ms. Marvel or

Wonder Woman and doing it well? Not so much of a stretch. I get it. But I want to see a good female writer on

Batman -- a well-known white male power fantasy. Or a good female artist, for that matter. Or both. And not just as a one-off. A good long run, the same kind that creators like Grant Morrison or Scott Snyder or Greg Capullo are afforded.

That would be interesting to see, on any number of levels. Hell, it

might get me to actually

read a new

Batman comic book for the first time in over a decade...! It would excite me a lot more than the next Straight White Male working on the book. I've seen

that a whole bunch of times.

Things like that are

starting to happen, but mostly in awkward fits and spurts. But corporations are often reactive as opposed to proactive. So I wouldn't say I'm "worried,"

per se, but I do see that there are some editors who often "cast" the creatives on the books they edit in a very stereotypical way. They need to get over that shit and realize that talent is talent. Gender, race, sexual orientation, etc... all these things should be secondary to whether or not a creator has the talent, the skill and the experience to do the job. And, to be painfully honest, there's a vocal segment of the readership who are often guilty of having those same blind spots. But I'll give them a pass. An audience wants what it wants and they don't have to justify why.

SPURGEON: From your perspective as a creator, do you find that a lot of publishers right now understand what you need to function best a creative professional. Is that underlying contempt you once described to me, is that still there?

CASEY: Talk about First World problems...! Look... some get it, some don't. Some try to rig the game. Corporate publishers, as a rule, are not entities you should ascribe actual human feelings to... any more than you would to a bank or a supermarket. They're all corporations. But I get your question.

Yes, I think that underlying contempt is still there, but it's there for different reasons now. The general empowerment of the creator these days annoys the piss out of the bigger corporate publishers. This is something I know from personal experience. Generally, in the mainstream of the last ten or fifteen years, the paradigm was to use Marvel and/or DC to make a name for yourself, then go off and reap the benefits of that name recognition on work that you actually own. It's like going to a sleazy prostitute to lose your virginity and learn how to fuck and then take that carnal knowledge and find true love elsewhere. And if there's one thing corporate comic book publishers know about... it's prostitution. But I've seen folks within those corporations get very upset when creators display any sense of self-respect or "defect" to greener pastures (and, by "greener," I mean situations where they own their work and can potentially make more money doing it).

I'm not sure if that paradigm works anymore, since

Marvel and

DC seem to be unable to turn newer creators into "names" like they used to (even though they certainly operate as though that were the case). So that might limit where those creators can go later. But that just means those newer creators have to forge a new paradigm. I mean, they really have no choice. It's sink or swim.

SPURGEON: What's the best comic you read this year?

SPURGEON: What's the best comic you read this year?

CASEY: Oh shit... you finally stumped me, Tom. I've honestly had to rack my brain to come up with something current that really affected me. There are things that came out in '16 that I know are really good... but I'm having a hard time coming up with one that I can definitively say was the "best" that I read. Keep in mind, you're asking a guy who's hoping to re-read Steve Gerber's

Man-Thing run over the holidays. I can tell you I'm psyched for your book on the history of Fantagraphics. At the moment, I'm reading Coppola's

Godfather Notebook. I'm also reading

Thank You For Being Late by Thomas Friedman. So clearly, I have much different reading priorities than chasing down the latest Hot! New! Release!

I'm not a diehard Wednesday warrior anymore. I would love for there to be a quick, obvious answer to your question that springs to mind. Unfortunately, there wasn't anything like that in 2016 that got me really excited, there wasn't anything where it seemed like new ground was being broken. Maybe I'm not looking in the right places. That's entirely possible. But I'm still pretty good at keeping my ear to the ground... and simply put, lightning didn't strike. The things that people seem to be getting somewhat excited about all seem like retreads to me, like things I've seen before. Now, like I said, that doesn't mean they're not well-executed retreads done by talented creators. A lot of them are. But no retread is going to earn that "best" spot on any year-end list that I make. Maybe 2017 will be better. Let's hope so, anyway..

*****

*

Officer Downe, Shawn Crahan and Joe Casey, November 2016, 88 minutes.

*

Officer Downe, Joe Casey and Chris Burnham, Image Comics, January 2017, $19.99.

*

SEX, Joe Casey and Piotr Kowalski, Image Comic, series, comic book, $3.99.

*****

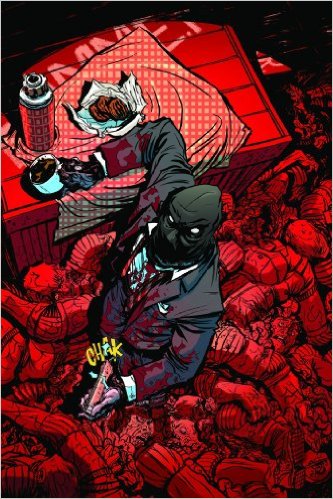

* image from the

Officer Downe movie

* photo of Joe Casey provided by the writer

* image from the

Officer Downe movie

* gorgeous cover to newest edition of the comics, with a lot of movie tie-in material

* the

Dark Reign: Zodiac project with Nathan Fox

* panel from

SEX

* cover to one of Casey's two comic-book collaborations with the late Steve Dillon

* the great Steve Gerber-era on

Man-Thing, a Casey re-read

* Chris Burnham's art on

Officer Downe [below]

*****

*****

*****

posted 5:00 pm PST |

Permalink

Daily Blog Archives

November 2019

October 2019

September 2019

August 2019

July 2019

Full Archives