November 16, 2013

CR Sunday Interview: Gene Luen Yang

CR Sunday Interview: Gene Luen Yang

*****

Gene Luen Yang

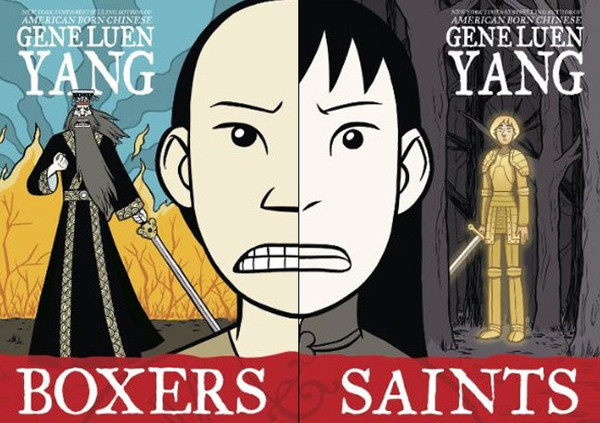

Gene Luen Yang is the award-winning author of

American Born Chinese and one of the nicest men in a field stuffed with nice men. His latest work is two books:

Boxers and Saints, which may be read separately or apart. Each book unpacks events of

the Boxer Rebellion from a radically different perspective. One view is that of a young Christian woman who dreams of becoming a warrior maiden without really understanding even the basics of what that might entail; the other is that of a young male villager who confronts Western visitors to his country with a force of arms. Their lives overlap briefly, although only one of them can even remember meeting the other.

Boxers and

Saints are historically informed without being lashed directly to history. For one thing, there are several supernatural elements in each story. While Yang isn't all the way forthcoming how much those moments are "real" within the framework of the saga, they certainly reflect the worldview of the two stories' young, naive protagonists. Yang's sympathy for these characters -- based on their age and lack of experience and even the limitations of their education -- shines through on every page.

I had the hardest time getting my act together in order to talk to Gene, and I'm grateful to both the cartoonist and to the publicist Gina Gagliano at First Second for finally setting something up. -- Tom Spurgeon

*****

TOM SPURGEON: So did I read these things in the right order? I went Saints

/Boxers

, and I realized when I was looking at some on-line information about the book that the two books are sold as Boxers

/Saints

. Did you care how people read them?

GENE YANG: I was hoping you could read them in either order. From a few comments I've received back from people it sounds like -- for most people at least -- it works better if you read the bigger one first, if you read

Boxers first.

SPURGEON: Do you think it changes the reading experience to read them in a different order?

YANG: I don't know. One book kind of spoils the ending of the other one, so it... [pause] I don't know. From a few of my friends who have read them, they say

Boxers gives you more of an overall picture, and tells you what the Boxer Rebellion is about, and Saints gives you more detail with its focus on one small community. Not everybody felt that way.

SPURGEON: Now did you create

them in a specific order? Did one come before the other?

YANG: I outlined them together. I ended up drawing

Boxers first.

SPURGEON: Did you feel a lot of pressure doing these books? Because while you have done work since American Born Chinese

, I have seen these two books presented as the official, major-release follow-up. Did you feel pressure because of that?

YANG: Yes. [laughter] Yes to all of those questions.

When I started in comics, I never had expected to make any sort of real money at it. I started in the mid- to late-'90s, and I think most of the people that started then... this is when we'd go to

Comic-Con and there would be nobody there so we'd walk up to the front and buy a ticket. I remember listening to -- I don't remember who it was -- one of the big publishers predict that comics in America would go the way of poetry. That it would become this very niche market, produced and read by a very small market in America. I always just expected for this to be something I do on the side.

So when

American Born Chinese came out, it really turned things around for me. It was unexpected. It was really, really unexpected. I started making money at comics for the first time, and it was kind of crazy. I was really thankful that the book that came out right after that was a book with Derek Kirk Kim called

The Eternal Smile, which was a collection of short stories we did together. I was really grateful that I got to do a book with a friend I deeply admire for the follow-up project -- the immediate follow-up project. I felt that took some of the pressure off.

For this book, I definitely felt... I remember thinking that the industry is such a crazy place. It's hard to get in, but it's almost harder to stay in the game. I remember thinking that if this doesn't do well I don't know what's going to happen next. [laughs]

SPURGEON: At the same time, Gene, this new work is very ambitious, it's not like you did a sequel, or even something that adhered close to American Born Chinese

. It seems like you wanted to use that accrued capital on something you'd thought about for quite some time. Is that a fair assessment?

YANG: Yeah, I think so. I think so. I teach as part of

Hamline University's MFA program in creative writing. When I talk to my students about what they should write, I always tell them to tackle the project that scares them a little bit. That's what I did with

Boxers and

Saints and with

American Born Chinese. But especially with

Boxers and

Saints. I didn't know very much about the Boxer Rebellion. I'd never done anything that was research intensive. It was a little bit scary for me going in. I thought, "If I'm going to fail, I want to fail big. I want to fail in a big way." [laughter] That got me to jump in.

SPURGEON: So was any of that fear justified? Were there elements to making this book that were more difficult for you than some others?

YANG: Yeah, I think

Boxers and Saints was... well, first, I'm not an historian. This was the very first time I'd ever done any sort of research. All the way through I had this fear that when I was finished with the book that pieces of it would just be inaccurate. And it's true. Even now, it's true, right? There are pieces of it that aren't historically accurate. I was constantly worried that I just didn't know enough about the period.

In the end, the way I got myself to stop researching was to realize that even with

American Born Chinese and the other books I've set in modern suburbia, I'm not trying to replicate modern suburbia, I'm trying to create to this cartoon world that's based on modern suburbia. So with

Boxers and Saints, I was basically trying to do the same thing but with turn of the century China. I wasn't trying to replicate turn of the century China, I was trying to create a cartoon world that was based on turn of the century China.

SPURGEON: In a couple of your other interviews, you said you went into this project hoping to find the answers to a couple of questions. I assume that that encompasses the history you're dealing with, but that also there are thematic questions, like about the nature of religious experience, or the dualities that are represented in the book that might have resonance for you as someone as Catholic. So I assumed multiple questions. What I wonder is how effective art is for you in answering those questions? Did you get to some answers, do you think?

YANG: I think so. I did get some answers. I think in a lot of ways this was me wrestling with things on paper. Doing a book gives me time to think through questions I wouldn't normally have time to think through.

SPURGEON: Can you identify something where you might have a different opinion now as opposed to where you were when you started the book?

SPURGEON: Can you identify something where you might have a different opinion now as opposed to where you were when you started the book?

YANG: I was really surprised by how at the time the Europeans and the Japanese had this really horrible relationship with the Chinese. It was a classic oppressor/oppressed relationship. I was also very surprised by the commonalities I found on the two sides. Even though they had this horrible relationship with one another, each of the cultures contained reflections of the other. I think I was very impressed by this common humanity.

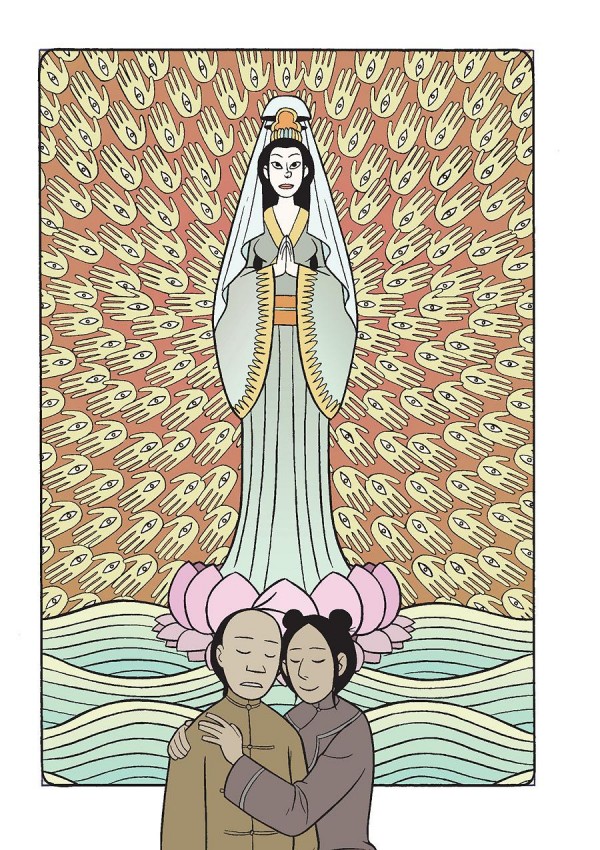

One of the things that I really wanted to work into the project, even before it was formed in my head, was this image of

Guanyin, the Goddess Of Mercy, the Chinese Goddess Of Mercy. Years ago at an Asian art museum I saw an image of Guanyin, and she was surrounded by this halo of hands. Within each hand was an eye. I'd seen images like that before, but normally when the eye in the hand is drawn the eye is drawn horizontally. But in this case, in this particular painting, the eye was drawn vertically. So it looked like a crucifixion wound. I was struck by that, the familiarity in iconography. In Chinese medicine, the eye is considered one the seven holes of the head. So this eye in the hand, this hole in the hand, bridged western/eastern religion.

Later -- these are things I wasn't able to work in the book -- I learned that the hand with the eye in middle, can be found in Jewish tradition, where it's known as the

Hand Of Miriam. It's also found in Islam. So there's something universal about this iconography around compassion. Within Buddhism, the hand is the symbol of compassion. The eye represents that she wants to constantly look for suffering, and the hand represents that she constantly wants to relieve it. And in the western tradition the hand with the hole in it is seen as a symbol of self-sacrifice and of compassion. It really struck me that there was something universal about not just the iconography but also the concept that the iconography presented.

SPURGEON: I would assume you have to be very attentive to working with iconography in any book, but with these two books you might have to be more focused than usual. Was that a specific challenge to that book, finding opportunities to find and use motifs and images to make a binding element between the two works.

YANG: Yeah. I think so. Whenever I'm doing a comic, always in the back of my mind I'm thinking about why does this story have to be told. Why is it a comic? Why does it have be told in panels? Why can't this be prose? I do try to leverage that a bit in my books. I do try to have a visual element that ties things together. In terms of the iconography, I guess some of it comes from growing up within the Catholic Church. At my home church, I was surrounded by visual symbols and icons.

When I was in my early adulthood I did this retreat that was led by an icon painter. That was a very profound experience for me, to see how symbols are weaved into spirituality. I think in a lot of ways, America is a very protestant place. The protestantism is woven into the fabric of who we are. It was interesting to be at that retreat and really talk through the visuals of spirituality. I think for the most part... I don't have a universal experience for this at all, but my experience of American spirituality is that it's very much tied into music, and it's tied into sound and it's tied into preaching and words. Right? Whereas I think for certain expressions of Catholicism, especially as you go East from Europe, the visual has a lot of importance. I think there ties between that and Eastern forms of spirituality as well, that the visual is very important.

SPURGEON: You have a very set style, a very recognizable style. We know what your work looks like and these new books are very recognizable as yours. I think that we have an appetite for stories in any number of styles now. We have a broader range of acceptance for style.

YANG: Yes.

SPURGEON: So how comfortable are you in your style, and do you ever strain against its limitations? Do you ever wonder when you're working on a story if it might work better drawn in a different way? Or is this just the way you think now, where you know without thinking about it that this is the way you depict these cartoon worlds?

YANG: I feel like my style is really... limited. [laughter] That's actually something that's always bugged me, especially after working with Derek. Some of us are illustrators, artists, and I am definitely not one of them. Derek has a very, very flexible style. He's able to tailor his art style in service to a story. I don't feel like I can do the same thing. I don't feel I have the chops to do that. I feel like I've been trying to push my art style, but it's just in sketchbooks. When I get to doing work that I know is going to get published, maybe something freezes inside of me and I default to this style that I'm used to and that I'm comfortable with. It isn't necessarily the most... I wish I could vary it up a little bit more.

SPURGEON: Do you write around your style at all, do you think?

YANG: I am thankful that like you said that the reading appetite has expanded, and that there's less... I think part of it is shows like

The Simpsons and

Family Guy, right? You can't just think that because something is drawn a certain way it's going to deal with certain topics and it's not going to cross certain lines. I'm thankful for that. I've been a beneficiary of that, because I have this limited, slightly cartoony style. I can tackle more serious topics.

I definitely want to push it different directions. [laughs] One of my big wishes is that I wish I had gone to art school.

SPURGEON: You said you work in a sketchbook. Do you get time to sketch? You're obviously working at it all the time, right?

YANG: I don't know if I sketch. I find time to doodle. I still have a part-time day job. I usually keep a piece of paper by my desk and when I'm waiting for stuff to load... I'll do some doodling.

SPURGEON: How right-side-of-the-brain are you when it comes to page structure? I think that's a strength of your work, that the physical construction of your pages allows for natural variation in pace. You have a nice sense of rhythm on the page. I wondered if that comes naturally to you, or if you have to break it down in explicit fashion while you're writing.

YANG: The way I do scenes is I'll write on a piece of napkin or on a piece of scrap paper the dialogue and the action beats that will happen and maybe do a few sketches here and there. From that, I'll try to figure out how to use the page turn, the pacing, and what belongs within each panel. I try to be really careful about that. I don't think I've yet explored how to change scenes in the middle of a page. That's something that Adrian Tomine does very well, it really amazes me. I'm very reliant on the break between pages, that natural shift that happens in a reader's mind. I'm still reliant on that for my scene breaks. But that is something I think about consciously. The beats and how many panels on a page and how the panels will flow one from the other.

SPURGEON: Did the supernatural elements of both books require specific thought and planning on your part? I wonder about the "reality" of those moments in comparison to the non-fantastic moments depicted. You seem to favor the side of these supernatural moments having a reality to them, that there's a consistent logic to them that can't really be explained. And yet there's still enough of a hedging against it to leave open the possibility that these are subjective experiences poorly understood and articulated.

YANG: I remember with

American Born Chinese really struggling with this transformation where the main character becomes white. Right? I really struggled with whether that was an actual, physical transformation or whether it was just in the character's head. In the end I couldn't decide. So I tried to write that book in a way where either interpretation would work. As I was working on

Boxers and Saints I don't know that I ever explicitly made that same choice. I think it just kind of came out this way. I think in a lot of ways it flowed from those choices I had already established with

American Born Chinese.

I felt very comfortable in the magic realism, in this in-between space of not knowing whether the spirituality is real or not. Maybe that comes from my own life as well. I think even though I'm part of a faith tradition now, I feel like I've always struggled with doubt. I don't think that's just me, either. I think most of us who are adults who are part of a faith tradition struggle with doubt. Not to get too religious, but one of the passages in the Bible I really like is one where Jesus goes into this rich man's house and heals his daughter. Before he gets to the house the daughter is dead. They tell Jesus to go away, because he's to late. He says to the people that are mourning, "She's not dead. She's just sleeping." And they laugh at him. Then he goes in and has her get off the bed and ask for something for her to eat. This statement that she's not dead, that she's just sleeping, there's a lot of debate about that in Christian circles. The interpretation that I like the most is that introduces and element of doubt. That even within a faith tradition there's room for different interpretations. There's even space for doubt. He doesn't impose belief on you, he allows you the out of believing that she's just asleep.

So this question as to how much of it is real, and how much of it is in your head, I think I always feel most comfortable in the gray spot in between.

SPURGEON: A connection between two leads is that they both exhibit a certain amount of naivete, partly because each operates from limited information. They're barely educated. It seems like you have sympathy for your protagonists. What's it like to deal with characters that have a limited amount of information, that are still piecing together as they go their reality? You can track the story in terms of how they interpret the events -- in addition to tracking it through the events themselves. I wonder if that was intentional, to provide two characters that see the world in that way.

SPURGEON: A connection between two leads is that they both exhibit a certain amount of naivete, partly because each operates from limited information. They're barely educated. It seems like you have sympathy for your protagonists. What's it like to deal with characters that have a limited amount of information, that are still piecing together as they go their reality? You can track the story in terms of how they interpret the events -- in addition to tracking it through the events themselves. I wonder if that was intentional, to provide two characters that see the world in that way.

YANG: Part of that was the historical record, particularly on the

Boxers side. A lot of the

Boxers were poor, uneducated peasants who lived really, really difficult lives. So I wanted to stay true to the historical record. On the other side, too, with Four Girl, I think that naivete, that lack of knowledge about the other, I think that was a part of early convergence. Growing up in that Chinese church, a lot of the folks didn't have a complete view of what this faith tradition was before they came into it. They had to learn. I wanted to stay true to that as well. I think that's true of a lot of us when we take on another piece of identity, whether it's religion or a political affiliation, usually we don't have full knowledge. Maybe even some of what we know is wrong. And in a lot of ways we find ourselves, we find our identity as we learn about this tradition we joined with only partial knowledge.

SPURGEON: It occurs to me that both of your leads have an identity through story. They have a sense of themselves as part of a heroic narrative, even if they don't fully understand what the entails -- that ignorance is particularly relevant to the case of Four Girl. She interprets reality in terms of the stories she has to do so.

[pause]

There's no question there, Gene. I'm just talking now. [laughter]

YANG: I think that's part of how I grew up. I think that's both a Chinese thing and a Catholic thing. In Chinese culture, you sometimes talk about your present in terms of the past. I read about how generals on both sides of the communist revolution would examine current plights in terms of historical Chinese battles. I think that's a really common way of talking about things. My parents talked that way. When we talked about choices we had to make at school, they would bring up these stories from the past. Or old stories from their own life histories.

SPURGEON: There are two scenes, one in each book, that I wanted to ask you about. They were both moving scenes. The first is I wondered after the nature of the religious experiences Four Girl has at the end of her life. She ends up in a very different place than her narrative would have you believe she's going -- I'm talking about those last moments of her life where she prays. I thought that was moving, and I wondered if you could provide some insight as to the exact nature of what happened to that character.

YANG: I'm really attracted to the spirituality of -- I don't know if you know Henri Nouwen. He was a Dutch priest that spent much of his life working with the mentally handicapped. There's another saint named St. Theresa of Luzere. Thomas Merton as well. Their spiritual understanding is that the small things matter, and the small kindnesses really matter. I think when I was in my early 20s, my friend and I would have these talks about our calling in life, where we might fit in the world, how we could change the world. Normal post-adolescent idealism. There are a lot of feelings about that, and how you find your calling.

Now I'm 40. And I still hang out with a lot of those same guys. And we're still asking those same questions about our place in the world, and what we should be doing with our lives. I think that the spirituality of a Henry Nouwen, what they point to is that even if you never get answers to the big questions, the small kindnesses still matter. The small interactions you have with human beings on a daily basis, those are still important.

So I think the scene I wrote at the end of

Saints was sort of built around that. Four Girl never got answer to the question of where she fit. She wanted to be like Joan Of Arc. Did that mean she was supposed to join the Boxers, or that did mean she was supposed to defend this Catholic faith? She never gets an answer to that. Even though she doesn't get that answer, and her life ends in a tragic way, her small kindness still matters.

SPURGEON: The scene that struck me in Boxers

wasn't the actual end but near it. You introduced a story element of a library where certain treasures of Chinese culture were kept. I don't if that was an historical element you wanted to fold into your narrative proper, but you spend some time there and you spend time on the specific value of that place. You then move very strongly into the tragedy of destroying that specific place in order to see to a certain military goal. I wondered if you might tell us how to engage this specific story element, this place upon which you dwell a bit so near the end.

YANG: That was historical. That was an historical event. There really was a library and the Europeans thought the Chinese would touch it so they didn't guard where the library was. In the end, the Boxers burnt it down -- although I just spoke to this scholar from China, and there is some uncertainty about that. There are certain interpretations that say the Boxers didn't mean to burn it down, and that the wind shifted and it caught on fire.

The library was really full of these treasures that were irreplaceable. These scrolls and these stories that are now lost. It was a real tragedy.

SPURGEON: It must have hit you that way, because you so strongly emphasize it. It's not like you toss the information off in a graph of text. You spend some time there, and have your characters visit.

YANG: I feel sad about it. [laughter] I feel really sad about it. I also thought there was this irony. The Boxers believed they were embodiments of story. They were inspired by Chinese stories, and at the very end, that's what they burned down. It seemed like there was something very, very tragic there. And of course in that interpretation they

mean to burn it down. That was the one I used in my narrative. I think that's a human thing. Sometimes when you try to save something you destroy it. It's part of the tragedy of who we are as a species.

SPURGEON: You mentioned choosing a specific interpretation, and if I remember correctly the story from the Bible you told earlier, that's one of those stories that appears in multiple Gospels but it's different telling to telling. Dead in Mark, alive in Luke.

YANG: That might be true.

SPURGEON: One thing I know that happens when people deal with history for the first time in service to art is that they're stunned by the level of interpretive issues involved.

YANG: Yeah.

SPURGEON: Was that something you encountered? Did that have an effect on the choices you made? Were you perhaps more conscious of the choices you make in our work now that you realize there are so many ways you can go? That has to be maddening, in a way.

YANG: I think that's true. One of the things I encountered early on is that no one is really sure how the Boxer Rebellion got started. It was started among these poor communities in China, and because it was among the poor it wasn't well-recorded. The beginnings of the movement weren't well-recorded. We don't have a lot of historical record about the Boxers until they got into the main cities and interacted with the Chinese in power and with the Europeans.

In a way, this gave me a lot of creative leeway. There are a lot of places missing in the historical record that I could fill in. Just with things out of my imagination. But I do feel weird about it, I try to be really clear that this is historical fiction. This is a piece of fiction set in that historical time period. There are times when I did deviate from the historical record. Like for instance, there's a character in my book named Baron von Ketteler, who's the German ambassador to China. His death in the book is not the way he actually died in history. That was a dramatic choice that I made.

SPURGEON: Do you have an ideal reader?

YANG: I don't know. My Mom, maybe? [laughter] Maybe Derek.

I think I fit pretty well into YA. That wasn't a category I chose for myself. That was something First Second chose for me. Now that they've chosen that for me I do feel like that's a pretty comfortable place.

SPURGEON: You've mentioned Derek a few times in this interview... do you have a peer group? Are there cartoonists you think of as your peers, people with whom you have a lot of commonalities, and a shared professional experience?

YANG: Oh, yeah. Absolutely. Derek is one of them.

Jason Shiga. I feel like I started with a crew of Bay Area cartoonists. Most of us are still at it.

Jesse Hamm is part of Periscope now.

Jesse Reklaw was part of that.

Thien Pham and

Lark Pien. Most of us are still at it. I feel like those are my peers. That was my art school, hanging out with those guys.

SPURGEON: You mentioned your insecurity earlier... can you see more books in your future now? Is it easier for you to see the next 15-20 years of you doing comics as surprised as you were by the last 15 to 20?

YANG: Fifteen to 20 is a very long time.

I do want to keep making comics. I don't think there's a question in my mind about that. The question is more about scale and how much of my I am able to devote it. And that depends on all of these practical things. That depends on how much money I can make doing comics. How much money I'll need to support my family. I feel hopeful. I'm really thankful for all of the opportunities that work with First Second has given me. So yeah, I feel hopeful. I feel hopeful about my future as a cartoonist.

*****

*

Boxers, Gene Luen Yang, Color By Lark Pien, First Second Books.

*

Saints, Gene Luen Yang, Color By Lark Pien, First Second Books.

*

Boxers And SaintsGene Luen Yang, Color By Lark Pien, First Second Books.

*****

* cover to the new work

* photo by my brother Whit Spurgeon, maybe

* art from

Boxers and Saints hopefully well-explained by contextual placement, except for the final image below, which is just from a scene I like

*****

*****

*****

posted 8:00 pm PST |

Permalink

Daily Blog Archives

November 2019

October 2019

September 2019

August 2019

July 2019

Full Archives