December 31, 2012

CR Holiday Interview #13—Jason Grimmer

CR Holiday Interview #13—Jason Grimmer

Jason Grimmer

Jason Grimmer is the manager of

Librairie Drawn And Quarterly, the bookstore run under the wider

Drawn And Quarterly umbrella. That a few publishers are running retail establishments is an intriguing story of the last several years in comics. There are all sorts of reasons why this might be a good idea for a publisher, not all of them vague buzzwords like "branding," and we get into a few of those below. I'm also generally happy to talk to members of the D+Q team because that's an important comics publisher with only a few, vital cogs.

Grimmer I don't know at all except as a presence in the comments threads of Facebook threads fostered by various other D+Q employees, alt-comics' go-to source for cheap, barely-penetrable, on-line entertainment. Google revealed very little other than he was once a prominent employee at Vancouver's

Zulu Records, a model indie music store. I got a bunch more information from fellow Drawn and Quarterly people, but I'm still unclear how much of what they told me is true. I tweaked the following a tiny bit for flow. -- Tom Spurgeon

*****

TOM SPURGEON: Jason, I know very little about your background. I'm told that you went to school for broadcasting, were one of the prominent employees at Zulu in Vancouver and that you even once called stock car races, but I'm not sure how much I'm being messed with. Can you talk about your background, how you ended up in retail? Was comics a part of your background?

JASON GRIMMER: Once I'd graduated from high school I figured I should go to school for something and so I chose radio broadcasting. I realized pretty soon it wasn't for me. I liked the news-gathering, copy-writing, and voice-over aspects of it but not the cultivating of a wacky on-air personality aspect -- which was encouraged. [Spurgeon laughs]

Though I barely remember finishing the two-year course -- indeed, I only discovered I'd actually graduated two years ago -- I did get to do my practicum at a radio station in

Calais, Maine and loved it. I was given free-reign to write copy, produce and voice commercials for local businesses, and it was a blast because I could create characters and use their library of sound-effect records anyway I wanted with absolutely no one over my head judging my work. When that ended and they couldn't hire me because of my Canadian citizenship, so did my broadcasting career. I knew it would never be better than that. After that, yes, I accepted a job as stock-car race announcer but I quit after one shift when I realized they weren't joking when they told me the pay was "all the hot dogs you can eat during your shift."

SPURGEON: Yeah, that's... [laughs]

GRIMMER: After a succession of short-lived bad jobs in various blue-collar towns: a bartender and DJ at a scummy biker/ dive bar (which I quit mid-shift one night after one particularly terrifying patron asked me "are you gonna play '

Witchy Woman' or do I have to take you out back and beat the shit out of you?"), at a car wash run by an ex-NHL player, and the overnight shift at a 24-hour video store, I picked up and moved across-country to Vancouver, B.C. where I eventually got a job as a manager at Zulu Records.

As far as comics go, yes, they were a very important part of my youth -- as important as movies and music were, anyway. I spent grades one through through as the sole

Anglophone in an

Acadian village and the

Peyo and Hergé I found in the tiny library at my school taught me how to read French. Also, my mother would bring me to used bookstores on a regular basis and I would stock up on whatever comics were there.

I remember liking

Conan the Barbarian,

Justice League,

Heroes for Hire.

Man-Thing, horror comics and

MAD magazines.

MAD was definitely a huge thing for me and I loved the weirdness of the humour and art -- which I found pretty subversive (Dave Berg creeped me out particularly). I kept thinking "I shouldn't be reading this," but was happy my mom let me. Loved Don Martin. I also read the comics in the

Playboy and

National Lampoon magazines my dad kept around.

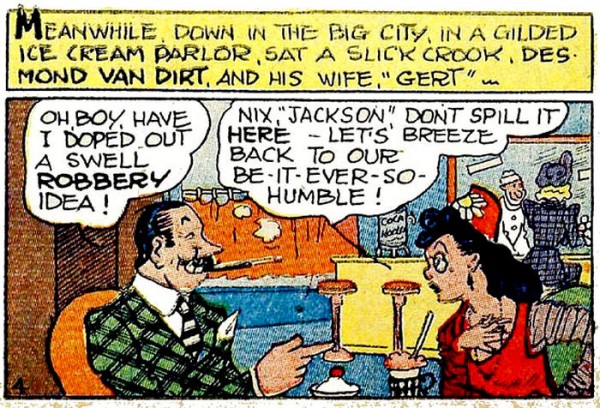

Dirty Duck kind of blew my mind and it was also where I first noticed

[Harvey] Kurtzman (I was happy to discover of his stuff through

MAD reprints, later).

A couple years later I got into the

Spider-Man [Steve] Ditko-era reprints but, even though I found

The Inhumans fascinating as a concept, I found Kirby's art to be too impenetrable for me, at the time. Later I discovered the difference between

DC and

Marvel and chose to make mine the latter (except

Legion of Super Heroes, which I found fascinatingly bad). I kept up with Marvel until

John Byrne's

Alpha Flight and then lost interest in super-hero comics completely.

I was always pretty aware of first-generation underground artists -- knew their names and some of their work -- but I didn't pay much attention to owning anything. Mostly read some stuff that my friends' pot-head, older siblings had laying around. Much later, a friend lent me some issues of

Eightball and I started to pay more attention to comics again. A couple of years before I started at the bookstore, I started reading all the D&Q books I could find at my local library and the two that stuck with me -- and remain two of my favourites -- were

Seth's

It's A Good Life and

Gabrielle Bell's

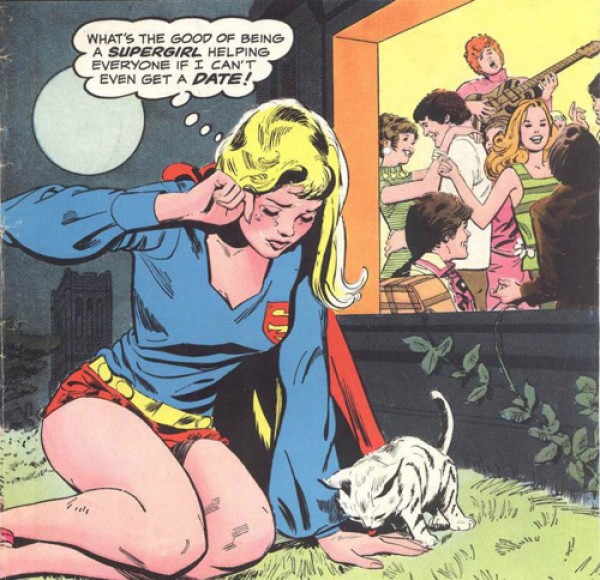

Cecil and Jordan. Those, along with

Chester Brown's

Louis Riel (which I read much earlier) were my real entry points into D&Q.

SPURGEON: The Zulu experience seems like it would directly relate. Do you still use anything you learned in those days in the management of the bookstore? How do you look back on those experiences now?

GRIMMER: I worked at Zulu for around seven years. It was there that I discovered that, even though I believed my taste to be discerning, that I also loved researching and immersing myself in stuff that I thought I should at least find some appreciation for, in the hope that it would take. You know indie-records stores (and I would imagine this goes for comic book shops as well) are not always considered places that hire open-minded people, but that's how it really is and should be. The people who work there and the patrons that support them have invested themselves in knowing what's good about everything. These types of shops are, in many ways, the most important places in any city and can help shape the cultural life of the city or town they are in, if handled correctly. You can spend days searching for things on the internet but if there's a place in town that narrows it down just enough so you can get a foothold, it can change your life.

We stock things we love and can get behind but we also bring in things that our clients consider important. Generally, if it's in the store, there's a reason for it and we should be able to explain why it's there. We have a chance to alter the cultural landscape of our city and we should recognize and embrace that responsibility. We need money to stay open, sure, so we need to sell books, but in that regard we are also incredibly fortunate. Our clientele likes and buys the books we bring in so we don't have to worry too much about stocking huge amounts of million-selling books that we don't care about. This is the difference between

Amazon and a Zulu, between Amazon and a Librairie D&Q. When I was a kid with hardly any cash, I depended on the clerks at certain record and book stores to steer me in the right direction. Not necessarily tell me, "You have to have this or you're not cool," but if they could explain to me what something was about, where it fit in and why it was crucial for me to at least know about it, I was sold. If you can do that, you can consider what you do is important, in my opinion anyway. A knowledgeable, interested and approachable staff is integral to the success of this kind of business.

SPURGEON: I know the store celebrated its five-year this Fall, and I understand what they were thinking when they started it, but I'm not sure when you became involved. In fact, I'm not even certain how you went from Vancouver to Montreal. How did you end up with the gig?

SPURGEON: I know the store celebrated its five-year this Fall, and I understand what they were thinking when they started it, but I'm not sure when you became involved. In fact, I'm not even certain how you went from Vancouver to Montreal. How did you end up with the gig?

GRIMMER: My girlfriend, Kathy, and I played in a succession of bands in Vancouver and none of them were really satisfying experiences for us -- besides the obvious camaraderie and drinking. I knew that I liked being creative and liked -- to an extent -- the business of music, but we just didn't find the hard work it took for such small returns to be worth our while -- especially now that we were in our thirties. We figured that if we stayed there, we would be stuck in the same rut forever -- forming a band, gigging, recording, and then suffering through yet another band break-up.

Once our daughter was born, it gave us a reason to look eastward, partially because we kind of disliked Vancouver and partially because all our family was back-east and our parents would have better access to their grand-child. A lot of our friends were talking about buying apartments and flipping them and, since we had no interest in that, we decided to visit our family for vacation and not return. A month later we were living in Montreal. We had neither jobs, nor substantial savings, but I was fortunate enough to, right-away, find a part-time job at a record and used bookstore that barely supported us while Kathy went to school for Early Childhood Education. It was a tough couple of years, I knew some French and Kathy none.

Our daughter, Addie, became friends with

Tom and

Peggy's daughter, Gigi, at pre-kindergarten (

Chris and Marina's son, Charles, also attended) and our resulting friendship with her parents led them to offer me the management job at the bookstore when the position presented itself a year or so later. Tom, Peg, Chris and Marina are amazing people and have been very good to my family. Gigi and Addie still hang out almost every weekend, Tom and I drink together at our monthly comic book club meetings, Peggy and Kathy are in book club together, and we have a lot of shared friends, so we're pretty close. I'm the only person in this city that Tom seems to know who he can have really deep discussions about the

Velvet Underground or

Pavement with, so I have a huge responsibility in that regard.

SPURGEON: You're in a comic book club with Tom Devlin? I think I need to know as much about this as you're willing to tell me. Is there anyone else in this club? How does it work?

GRIMMER: Yeah, it's me, Tom,

Joe Ollmann,

Pascal Girard, D&Q managing editor Tracy "Hamcups" Hurren, store staffer, Marie-Jade Menni (who, incidentally, did her thesis on the Hernandez Bros.), and our good friend Howard Mitnick.

Matt Forsythe used to be in the club as well, but recently moved to Hollywood, I believe. We meet in the store after it closes. We all get a chance to choose a book for each meeting. We've done

Death Ray,

Acme Novelty #19,

My Friend Dahmer,

Dungeon Quests

1 &

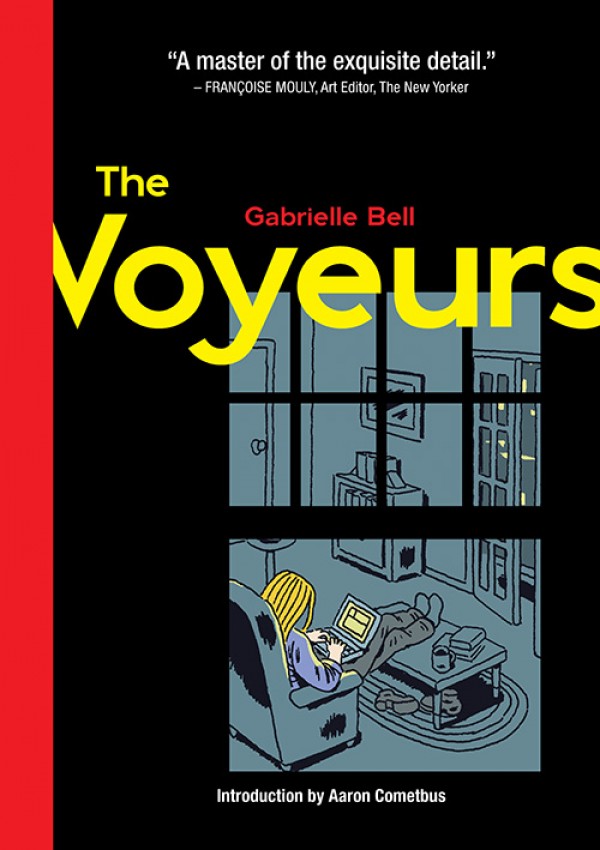

2,

The Voyeurs and maybe a few more that escape me right now. We don't all always like all the books but there's always someone in the group who does and so we end up reading stuff we never would usually. We try to keep the conversation focused on comics but that can be tough sometimes as there tends to be a lot of beer involved.

SPURGEON: You know, I'm not even sure I know the size and scope of the store. Can you break it down in terms of things like the size of the space, the size of any and all storage you might have, how many people work there, how many hours the store's open and what that means in terms of employee hours, how many events you run, that kind of thing?

SPURGEON: You know, I'm not even sure I know the size and scope of the store. Can you break it down in terms of things like the size of the space, the size of any and all storage you might have, how many people work there, how many hours the store's open and what that means in terms of employee hours, how many events you run, that kind of thing?

GRIMMER: The bookstore is somewhere around 800 square feet. There are two shelves near the back and by our stage where we store overstock and there's some space under the shelves for overstock as well. Honestly, everything we have is pretty much all on display, which is to say a lot. Right now, we have tons of boxes filled with

Building Stories all stacked neatly at the back waiting to be opened and shelved as the ones on the floor sell. The store is packed, but organized. It's a lot like my apartment in that way. As I mentioned there is a stage at the back and whenever we have an event we move all the tables to the side and put out chairs. This year we re-shelved the entire store so now we have wooden shelves that reach the ceiling and are better able to showcase some of our more beautiful and interesting books, whereas before they were all mostly spine out on black metal shelves. It's a beautiful space, really.

There are six staff members currently on the payroll. Myself and five others, but I'm the only full-time employee. The staff share most responsibilities but also has distinct duties as well -- French book buying, graphic novels etc. -- and I hire people based on their particular strengths. I'm fortunate because a lot of my hires come from a pool of the best former D&Q interns. If someone worked especially well in the office, Peggy will let me know and I interview them. The final decision is mine but if Peg and Tom and Chris have spent time with someone and suggest them, a lot of my work is done already. During regular season (that is, non-holiday season where we're open everyday from 10 AM until 9 PM) we open at 11 AM and close at 6 PM Sundays to Wednesdays and 11 until 9 the rest of the week. I'm there for two hours before we open so I can get ordering and other work done before we open. I don't have an office and am at the cash all day, so that time is necessary for me. I do a lot of researching books and booking events while having a coffee.

Events-wise, I'd say seven or eight events a month. More during the fall. One of my mandates when I took the job was to open the space up more for the Montreal literary community's use. We are constantly hosting launches by Concordia and McGill professors and students and I think this was the reason we were the only bookstore featured in

Time magazine's article on the Montreal Literary scene... Next fall I plan on starting the Librarie Drawn & Quarterly Reading Series where we'll host a few big-name authors off-site and then readings with other, lesser-known or emerging authors throughout two weeks in the store. I have a wish-list of big authors I'm always trying to get and I start really working on it in February so we'll see how it goes.

SPURGEON: How much of the store is D+Q-related material, how much is from other, similar publishers. How much is comics vs. prose?

SPURGEON: How much of the store is D+Q-related material, how much is from other, similar publishers. How much is comics vs. prose?

GRIMMER: One wall and shelf of the store is dedicated to D&Q, so -- and I'm really guessing here -- maybe 15%? People come from all over to see the "D&Q" store so we carry everything, of course. Besides that, the store is -- and please excuse the word, but it actually applies here -- curated, so we really only carry what we consider the best in almost all genres of literature. While we have lots of comics and graphic novels we also have a nicely maintained literature section. We have a small, but growing, poetry section, a theory section, art books, our favourite magazines, and probably the best English childrens' book section in town. We focus a lot on publishing houses that we consider to be D&Q kindred spirits:

McSweeney's,

Anansi,

La Pastèque,

Conundrum,

Nobrow,

Granta,

Toon Books,

New Directions,

Melville House,

Semiotext(e),

Koyama,

Fantagraphics, and more I'm forgetting right now. It all meshes pretty well with the D&Q aesthetic, so it works well.

SPURGEON: The anniversary article I read made a big deal about the exquisite way the store is curated. How much of the store's feel is you, do you think, maybe independently of a broader D+Q aesthetic?

GRIMMER: I inherited the shop so a lot of it was in place beforehand, and Tom and Peg and Chris' aesthetic is close to mine. I mean, I believe that was a big reason why the hired me and entrusted me with their store. What I've done is take what they started and kept moving in the right direction without having them feel like they always have to worry about it. They knew I had the right kind of buying experience and they knew what I liked, personally. We use

Book Manager as our POS and that's a massive help. They've been great and I do around 85% of my buying through that. I can track what sells and where and source out things from different suppliers pretty easily.

The office still plays a big part in the stocking of the store. They suggest stuff and the store staff does some buying as well… they all have great taste so if they consider something worthy, someone else is going to appreciate it as well. I don't question a lot of their choices, I learn from them. I could probably stock a whole store myself based on what I like and know about but you could also stock one based on what I don't know, so it's hugely advantageous to have this resource. There's also

Peter Birkmoe from The Beguiling whose brain I'll pick on a fairly regular basis. Besides buying, if any really big decisions are being made, we figure it out together and make things work. This is what makes the store as good as it is and the job so satisfying. I get to do what I like and enjoy a huge support system while I do it. I think it's working well.

SPURGEON: I will understand if you want avoid details, or maybe avoid the question entirely, but I hope you'll bear me out. Is the store profitable? You guys were quite up front in the anniversary article about grant money making it possible, and people in North America sometimes think everything in Canada is supported by the government forever.

GRIMMER: Oh yes, the great Canadian myth that everything here is funded by grants! Here's how I understand it: the office was able to secure a grant for the opening five years ago so they could fulfill the mission of providing comics, art and literary workshops and events to the public, which we still do. Tom does a graphic novel course and Pascal Girard does them in French. The amazing

Leyla Majeri does screenprinting workshops… I know this much: the store hasn't received any funding ever since, we are even unable to quality for library & institutional sales due to some bureaucratic red-tape. We are pretty much following the trajectory of any small business. I was told we were in the red for the first four years, and now, finally, we're in the black in our 5th year. Are we profitable? Well, it's an independent bookstore, so I think we all know the answer to that one. It's always a break-even affair. When you don't make any money the first four years, it's hard in the 5th when you come out a bit you hesitate to throw the word "profitable" around, as you can well imagine.

SPURGEON: I was wondering if you could talk about a couple of D+Q books, maybe a non-D+Q comics-related book, and a prose book with which you've done well. What are some of the distinguishing factors in terms of something that sells pretty well in the shop. How many would your best-seller for a year sell in a year?

SPURGEON: I was wondering if you could talk about a couple of D+Q books, maybe a non-D+Q comics-related book, and a prose book with which you've done well. What are some of the distinguishing factors in terms of something that sells pretty well in the shop. How many would your best-seller for a year sell in a year?

GRIMMER: Since I've been there I'd say the best-selling newer D&Q titles by a pretty wide margin were

Hark! A Vagrant,

The Death-Ray,

Paying For It and

Jerusalem. As far as non-D&Q goes, the

[Chris] Ware,

[Alison] Bechdel,

[Art] Spiegelman and Clowes back-catalogues in general are pretty huge and never stay on the shelves too long.

Otherwise, this year

Junot Diaz's This is How You Lose Her was big for us, which is a pretty cool for a hardcover fiction title as they can be hard to move in great quantities. It usually has to be a title that both the staff and our clientele embraces that makes a hard cover break out. Of course, we've had great success with local authors as well.

Rawi Hage,

Jonathan Goldstein… and this past year, mostly due to out very successful launch events with them, both

David Byrne's How Music Works and

Miranda July's It Chooses You were huge and we sold through hundreds of the books. What are great quantities in a year? I'd say a hundred or two, more in some cases. Quality of the title and the staff's love of the book definitely play a huge part in driving our sales.

SPURGEON: Does geography play a role in your store? I don't know where you are or anything about Montreal, but I know that bookstores can sometimes anchor a neighborhood. Are you a neighborhood store, too? Which neighborhood?

GRIMMER: We're located in the

Mile End, which has been a pretty hip area for the last decade. I guess the Arcade Fire hitting it big played a part in that. So did the cheap rent. The rent's gotten steeper now and as the younger students, artists, writers, and musicians all move north to the even-cheaper environs of

Parc Ex and

Petit Patrie, families are king. These families are mostly made up of

McGill and

Concordia professors and writers and artists and their children who are very invested in books and art (and mostly Anglophone) and so the store has become a kind of hub for them. The literature and children's section expansion is testament to that.

SPURGEON: Is there anything you wish you hadn't done, a step that maybe wasn't so fruitful, in the years you've been there? How do you feel you're still learning? Do you have room to try things and fail?

GRIMMER: Honestly, I've only been at the store for something like 18 months and I've been busy the entire time so I haven't had a lot of time to look back on anything I've done wrong. I don't think there's anything we've done yet that I would consider a failure. I put a lot of time into the store and I definitely have an amazing support system here so I have faith that any problem that may come up could be figured out. I'm a pretty careful person, generally, and everything I do with the store is worked out and thought through but I'm also aware that great things can't happen if you don't take chances. We would never let a great idea die on the vine.

SPURGEON: With the events, is there something that's key to making sure the events drive business to the store, as opposed to just being awesome events? I worked in a gallery once that threw amazing parties, but did so in a way that never led to people buying stuff off of the walls.

GRIMMER: Obviously, you can't sell 50 books at every event, but we always look at every event we book as potentially successful or we don't book it. There are a lot of considerations to take into account. A few months back, store staffer Julien Cecceldi did an amazing job when he decided he wanted to bring author

Chris Kraus to Montreal. Her books sell well enough for us and she's a store favourite, but we needed the resources to bring her here and book sales were not going to cover it so we partnered with Concordia University and did two events with her. One in the store and one at the school and they both did great. It was important to show people that we were willing to bring someone we thought was worthy. Sure it cost us a little but we knew it was culturally important. She had a great time and did two wonderful readings so that was, to me, as great a success as our 600-people sold out Byrne and Miranda July events. Yes, book sales at events are important, but future book sales are just as important and if you work hard and are trustworthy, people will support you.

SPURGEON: You mentioned people making a destination of the "D+Q store" -- do you get tourism attention? I know that was a factor in Subpop doing retail, that it's the kind of thing that gets listed as a city attraction and you get some business that way.

GRIMMER: Sure, especially in the summer. A lot of people think -- and hope -- that the publishing house is in the same building, but it's not. Soon after

Paying For It came out I had a young lady from California who told me she was a sex worker and that she just wanted someone at D&Q to know that she and her colleagues thought that Chester's book was tremendously important and that they really appreciated him for it. She knew we were a bookstore but she knew I'd pass it along. When authors are in town they generally always come by, and recently we had a customer get pretty excited when Peggy brought

Guy Delisle in. And Tom Devlin's usually by a couple times a week to drop off books or borrow my tape measure, so that can be a bit of a thrill. Kind of like if

Eddie Vedder stopped by the

Sub Pop shop to visit

Mark Arm and maybe borrow his guitar tuner while he was there.

SPURGEON: Is there a customer you think you should have more of you don't yet?

SPURGEON: Is there a customer you think you should have more of you don't yet?

GRIMMER: I think we could probably reach out more to the other Anglophone communities in Montreal as well. We've started to do that a bit and I think its working. I see more people from

Westmount and

the West Island than I did last year. We need to beef up our French content as well. There's a lot of great stuff out there and it would be nice to be able to showcase it. We've had more requests for French childrens' book recently as well. I think that would be nice. I hate to turn people away when they are looking for beautiful books we could carry.

SPURGEON: How do you fold in children's material into a wider-range bookstore? Is there any key to attracting that kind of business, or at least being able to serve that kind of customer?

GRIMMER: The children's books fit perfectly. It's seamless, really. We do a lot of research with them and I'm confident that we are on top of getting in the best of the best. Aesthetics and content guide us and the quality of the illustrations is as important as with our comics and graphic novels. Matt Forsythe,

Lilli Carré,

John Stanley,

Isabelle Arsenault,

Frank Viva,

Alain Grée,

Julie Morstad, their work adorns our walls and we love it. Like I mentioned before, the Mile End is home to a lot of families and so our kids section is well-perused. My daughter comes to work with me once in awhile if my girlfriend and my schedules don't work out and she just sits in one of the little chairs in amongst all those gorgeous books with a pile of books and reads for hours. Lots of kids from the neighbourhood drop by and just sit and read. I pay attention to what they like or what their parents like and I stock accordingly. Childrens' books are great fun to research and stock.

SPURGEON: Are you settled in, do you think? Do you imagine what the shop might be like in five, ten years? How ambitious are you, and what might happen that we might read about that tells us you're on your way to making those goals?

GRIMMER: I'd say, yes, we're settled in. Our significance is felt, I believe and my job is to make sure that continues. We're more able to get authors to Montreal then we were when we first started because we're not Toronto and I think that will only get easier. I'm working on it anyway and I feel positive about it. As far as the future, yeah that's hard to predict. On one hand I think the need for thirst for great, beautiful books you can hold in your and shelve in your home will never abate but who knows how the E Book biz will affect graphically driven literature? I mean, maybe someone knows, but not me. I worked in record stores for so many years, I saw when MP3s changed everything but yet, there a so many great little record stores still around, and them seem to be doing OK. I mean, they have my business, anyway, for what it's worth. I still buy books and records on a weekly basis and my daughter is growing up in an apartment surrounded by them, but how many of her friends have the same thing? A significant number of them probably won't feel a need to cultivate that kind of environment in their homes when they get older. Maybe my daughter won't either. In cases like that then our store and stores like ours are even more crucial as we represent something that people know in their hearts is important but may not think about all the time. I can tell you this, I deal with people on a daily basis who tell me how relieved they are we exist. It's symbiotic: they exist so we do too. Buy a kid a book, will you?

*****

*

Jason Grimmer on Twitter

*

Jason Grimmer on Tumblr

*

Librairie D+Q

*****

* photo of Grimmer and the store by Alexi Hobbs; rights secured for

CR by Drawn and Quarterly

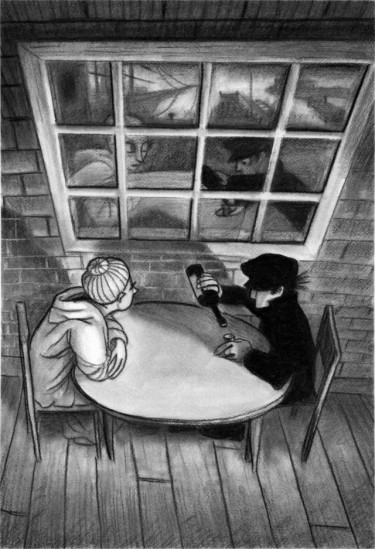

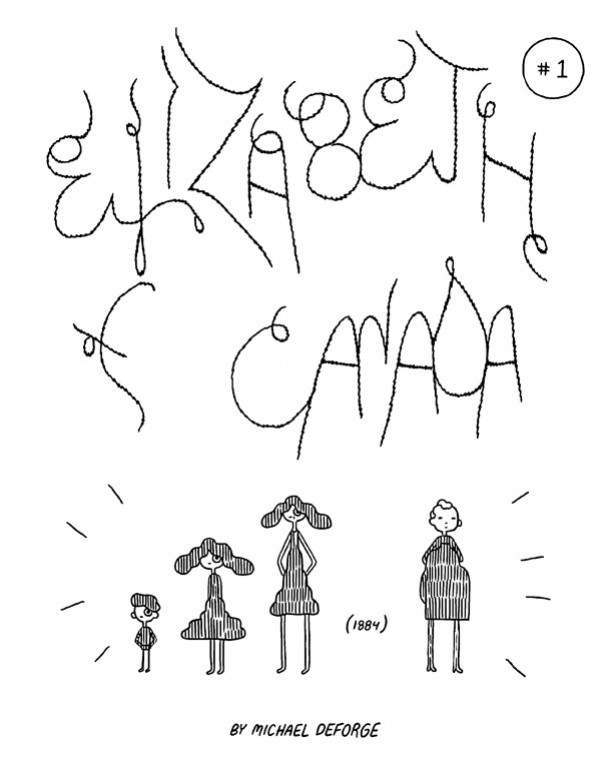

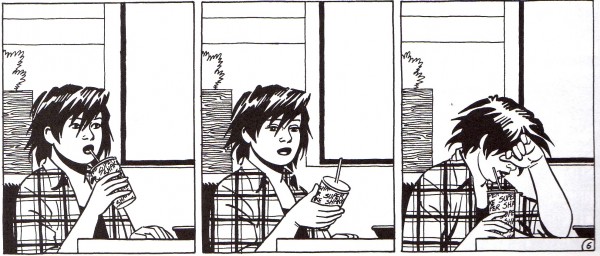

* Bobby London's Dirty Duck

* from

Cecil and Jordan

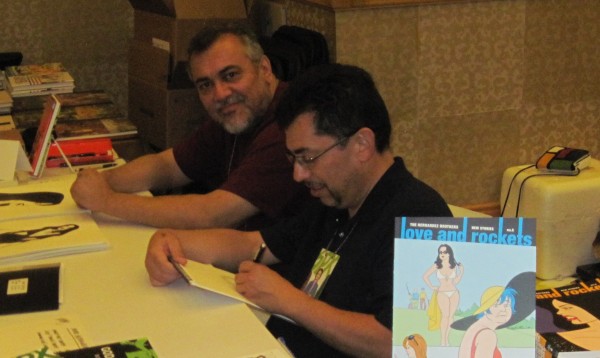

* photo of anniversary event by David Smith; rights secured for

CR by Drawn and Quarterly

* photo of store interior by Alexi Hobbs; rights secured for

CR by Drawn and Quarterly

* photo of books racked by Alexi Hobbs; rights secured for

CR by Drawn and Quarterly

* photo of David Byrne appearance by Richmond Lam; rights secured for

CR by Drawn and Quarterly

* a best-seller when it comes to prose at the store

* photo of window of store by Alexi Hobbs; rights secured for

CR by Drawn and Quarterly

* photo of Matt Forsythe's bookstore postcard by David Smith; rights secured for

CR by Drawn and Quarterly (below)

*****

*****

*****

posted 4:00 am PST |

Permalink

If I Were In Tokyo, I’d Go To This

posted 3:30 am PST

posted 3:30 am PST |

Permalink

Go, Look: Tommy Couldn’t See The Joy

posted 2:00 am PST

posted 2:00 am PST |

Permalink

Random Comics News Story Round-Up

* the writer Peter David

apparently had a stroke while on vacation. I wish him a full and speedy recovery, and further hope that he and his family have as much comfort and support as is possible during this trying time.

Update: Kathleen David has a lengthy update and fuller description of events

here.

* Rob Liefeld begins his

year in review.

* linking to Jordan Crane's

tumblr initiative isn't a new thing, but I sure like the look of some of the individual panels he puts up that way.

* you can catch up with a bunch of Dan Berry interviews

here.

* Scott Marshall on

Last Days Of An Immortal. Cory Doctorow on

Rise Of The Graphic Novel.

*

cartoonist/musician Nate Powell matches comics to albums.

*

Michael Cavna communicated birthday wishes to Stan Lee from various other august personalities.

*

these Christmas Day strip postings at the Library Of American Comics blog were a lot of fun.

*

here's a look at an image from a forthcoming Craig Thompson kids effort.

Here it is bigger. That should be fun.

*

wow.

* Jen Vaughn

reports on an Esther Pearl Watson show in Texas.

* I'm never quite sure how to cover

news of these juggernaut webcomics-culture based kickstarter campaigns, because mostly I just sit there with the Little Rascals shocked face, staring at them.

* hey,

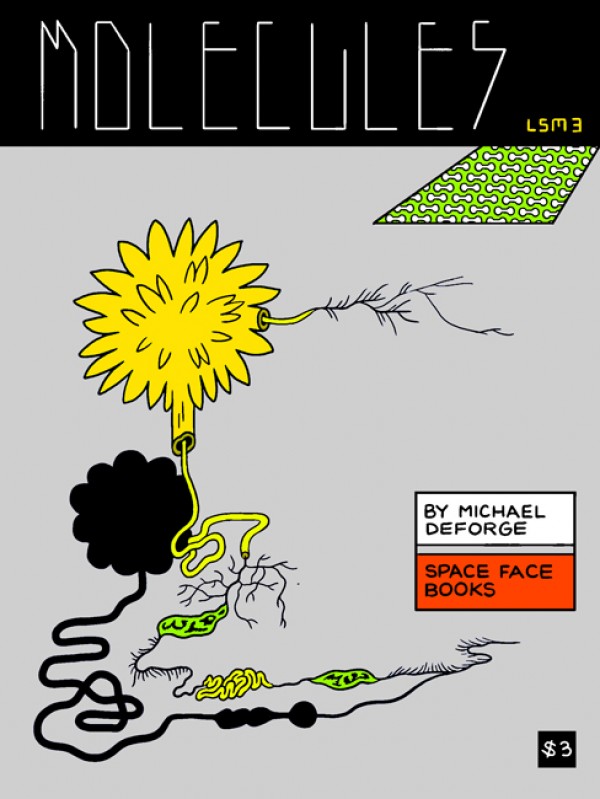

look at that CAKE ad. Lot of pressure on that show this year, lot of anticipation for it. Also found over there was

this Michael DeForge tribute to Leslie Stein.

* finally,

here are ten UK small-press comics you should own.

posted 1:00 am PST |

Permalink

December 30, 2012

CR Holiday Interview #12—Tom Kaczynski

CR Holiday Interview #12—Tom Kaczynski

*****

Tom Kaczynski

Tom Kaczynski had a very good 2012, escorting his line of Uncivilized Books to the trade and collections portion of the ongoing micro-publishing cotillion while seeing a fine book of his own out from

Fantagraphics.

Beta Testing The Apocalypse collects a number of Kaczynski's fine short stories from

the late MOME anthology and adds at least one major short story never published. His work reveals an inherent understanding of structures, of both the societal and formal/comics variety, which makes sense given his background in architecture. He is the only new publisher I've ever encountered in the alternative comics realm where people seem enthusiastically in his corner from the get-go, just sort of grateful he's arrived. Despite Kaczynski making comics for several years now, I have never been well-acquainted with him personally and as late as last year's

BCGF was openly mistaking his work for someone else's despite very much enjoying the individual comics as I came across them. I'm glad for this opportunity to have a better grasp on his significant presence in the world of comics, seeing as we should all benefit for years to come. -- Tom Spurgeon

*****

TOM SPURGEON: I want to apologize for the broad nature of some of these questions, but until I sat down and started looking at your work for this interview I'm not sure how familiar I am with your story. Let's talk about the publishing first. The initial impulse to publish: I know it's not unheard-of for a cartoonist that self-publishes and works with minis to go in that direction, but to make such a deliberate move the way you have with Uncivilized indicates there was some significant planning involved. Can you talk about the move into publishing?

TOM KACZYNSKI: Like you've said, I've self-published for a long time. Once I started working with

Gabrielle [Bell], working with her in mini-comics, we started getting a lot of good feedback in terms of what I was doing with her in designing her books, the quality of the little mini-comics being published. At some point, Gabrielle just sort of said, "Hey, do you want to do my next book?" [laughs] I wasn't a publisher at that point, really, I was just someone making mini-comics -- deliberately, but on a very small scale. So it took me a while to think about it. But once we sort of agreed I was going to do this, and I agreed to do it, I realized that for someone like Gabrielle, if that book was going to succeed, I needed to do something serious.

SPURGEON: How did the arrangement with Gabrielle come about with the mini-comics? I don't think I know that story, either.

KACZYNSKI: That was pretty simple. I'd known Gabrielle for a while. We were in the same drawing group in New York. We've known each other for years at this point. I started doing Uncivilized Books as a mini-comics imprint. She ended up coming to Minneapolis for a

Rain Taxi festival. We had talked about collaborating. Whether that was sort of a writer/artist collaboration, or something, we had talked about collaborating on

some level in the past. When she came for this

Rain Taxi festival in Minneapolis, I was like, "You ought to do something for the festival," because she was promoting -- I think it was

the Cecil and Jordan book. It would have been nice to make something for the festival.

So we talked about it and put together

LA Diary. The mini-comic. The collaboration was that she just gave me the comics, essentially, and I came up with the way I thought it should look, and designed it and everything. We got a lot of really good feedback on that, so we just kind of kept doing that. Part of this was also just --

Drawn And Quarterly had at that point canceled most of their pamphlet comics, and she was looking for another outlet in that vein: something small she could put out more frequently. It just kind of worked out. We kept working together, and at some point it seemed like it was a good idea to do the book, too.

SPURGEON: So you have this realization that you're going to do this book and that it's different than this other thing you've been doing. So what do you do then? Do you do research? Do you sit down and make a plan?

KACZYNSKI: All of those things. [laughs] I've always been a fan of publishing. I've admired what Drawn And Quarterly has been doing, what Fantagraphics has been doing, what

AdHouse has been doing,

Koyama Press... all of those people. You're always going to think -- well, not everyone, but I do -- I think, "Oh, that would make a good book." Or "I wish that book had been done a little bit differently." I have these little, nagging thoughts now and then about certain things.

When the opportunity came up to do this book with Gabrielle, once the decision was made, I was like, "I need to become a publisher, I need to research this thing, I need to find out what I do for distribution, I need to find out how to do this thing." I didn't want to be a publisher that stacks up a lot of books in their house. I wanted to have distribution from the get-go... I just wanted to. One of the things I looked at were a lot of smaller, literary presses, who seem to have a lot less harder time finding distribution than a comics press. It seems like the comics market is really still bound up with, although maybe not so much anymore, the

Diamond Direct Market. If you can't get into that, it's hard to get anywhere else. A lot of the larger distributors weren't, at least for a long time, interested in comics to distribute. Drawn And Quarterly and Fantagraphics and

Top Shelf and other publishers have sort of opened that door. I think there's a lot more interest in the smaller press.

SPURGEON: So who carries you? IPG or someone like that?

KACZYNSKI: I'm with

Consortium: Perseus, I think, owns them. They also do Nobrow. When I showed this stuff to them, they were basically interested in comics publishers, I think. I was also lucky in that they're based in Minneapolis. Maybe I had an easier time having access to them. [laughs]

SPURGEON: I remember one thing that was surprising to me when Fantagraphics and D+Q started teaming up with established distributors is how good a match they were for those companies -- they're oriented towards producing a lot of books, they have an established design aesthetic, they can do a catalog. Has that been a good relationship for you so far?

KACZYNSKI: I think so. They're very much focused on indie, literary presses. Some of the people they distribute are

Coffee House Press, people like that. The comics I'm interested in publishing tend to be on the literary spectrum of the comics world, and so I think we definitely fit in. So far, so good. I've only been there for one season so far. I can't speak to a longer relationship at this point. [laughter] But I've been very happy with it so far and I hope it continues that way.

SPURGEON: How has that first season gone, then? What's your learning curve been like in terms of getting a book out there? Where do you feel you've learned the most in terms of Gabrielle's book that you can now apply to this new wave of publications you're doing?

SPURGEON: How has that first season gone, then? What's your learning curve been like in terms of getting a book out there? Where do you feel you've learned the most in terms of Gabrielle's book that you can now apply to this new wave of publications you're doing?

KACZYNSKI: Promotion is hard. Although Gabrielle did a lot of heavy lifting on this. She has a lot of experience promoting her books in the past, and she was able to bring that over to this book. It helped a lot in getting the book out there. Learning about the whole... pre-publication stuff.

Publishers Weekly,

Kirkus Reviews and others, where you have to send them stuff early to get reviewed or even considered. Just sort of seeing the cycle. Where you start and how far ahead you need to be.

Before it was always, "Hey, we've got this thing. Let's put it out there. We'll worry about what happens to it later." Now it's sort of there's this book, and it's going to come out at a certain time, this is what we're going to do for it, this is how many copies we'll print, this is where we're going to print them, and here's the budget. Just making sure all that stuff happens was a pretty big learning curve. At least initially. Now I'm sort of settled into it, but Gabrielle's book was the test case. We did have a lot of extra time on that book, because we were working on it for more than a year before it hit the stores.

SPURGEON: You toured with her on it.

KACZYNSKI: We did a west coast tour. It was supposed to include my book from Fantagraphics, but I was late with the book [laughter] so my book didn't really make it until the very, very end where we did an event at

the Fantagraphics store and we had a copy to show -- not even sell. It was pretty fun. Gabrielle did a lot of heavy lifting in terms of organizing the tour, because she's done it before. She had some relationships with some of the stores that we did. Having Consortium back the book up helped a lot. There was a lot less stress about getting books to these places.

SPURGEON: It sounds like it naturally developed, but Gabrielle strikes me as a good choice for a first book, because she's not only talented but she's settled into what she does. Can you talk a bit about Gabrielle as a cartoonist? I think she's still a hard sell for certain comics readers. I know it took me a while to come around to what she does.

KACZYNSKI: Well, why is that? [laughs]

SPURGEON: I don't know. I'm not sure why. I needed to be immersed in her comics before I picked up on a lot of what she did. Her facility and talent is obvious right away, but the entirety of what she expresses took me some time. What do you

think makes her a special cartoonist? Can I ask you that broad of a question?

KACZYNSKI: [laughs] Sure. First of all, she's getting better and better, I think. I think she's very much, she has a very literary voice. Part of why there's been some resistance to her work in the comics world is the autobiographical thing. For a while there was a major backlash. I feel like there was a lot of that kind of work coming out in the '90s, and then in the early 2000s there was like, "We have to do something else. No more of this kind of work." I think she approaches it from a very different place than the 1990s autobiographical work. It's a lot more literary, more of a memoir. Her books do a lot better for me in bookstores than in comic book stores. Her voice is a lot broader in a way that may not latch on with comics fans -- that's not to say she isn't popular there, because she is to a certain extent. Just maybe not as much as she is in the general book world.

SPURGEON: The design work that you do... do you have a formal background in design?

SPURGEON: The design work that you do... do you have a formal background in design?

KACZYNSKI: It's kind of a formal background. I went to architecture school, which is sort of a design discipline, I guess. Not books, it's not graphic design, but it's a design discipline. I also spent a lot of time working... in college I worked for the college newspaper as a designer/art director. I never went into architecture professionally, but I went into design professionally after school. I've designed countless things. Web sites. Brochures. Anything you can think of. I hadn't done that much book design, because I wasn't in that world. It's something I always admired, and had friends that worked in that.

SPURGEON: Are there comics designers that you admire?

KACZYNSKI: Jonathan Bennett is an amazing designer. He's a great cartoonist and an amazing designer as well. I also like... he's not a cartoonist, but

Joel Speasmaker, he used to publish

The Drama. I admire his work. He has one eye on the comics world. He designed a bunch of stuff for the Brooklyn Festival this year, the Brooklyn Comics And Graphics Festival. I think

Jacob Covey at Fantagraphics really picked up the game for Fantagraphics' design.

SPURGEON: Enormously so.

KACZYNSKI: I feel like over the last decade or so the design of comics, graphic novels, has really taken a step forward.

SPURGEON: I'm pretty unsophisticated when it comes to design, but I like the overall look of your books. I like that you don't seem scared of type, working the titles into the overall visual effect. What do you think your strengths are as a designer?

KACZYNSKI: I don't know how exactly how to answer that. One thing that's frustrated me in the past about seeing certain books, like Gabrielle's work, is I've never really liked the way her books looked, to be honest. This isn't a big slam on anybody. We had a conversation where Gabrielle decided she wasn't a good typographer, essentially, so that was one of things we worked on together for her book. She's an amazing cartoonist, but there are a lot of amazing cartoonists that aren't good designers. There is this ethic in the comics world now that you have to do your own cover, do your own type. That's great if you're really good at that. But it doesn't serve everybody really well. That's something I wanted to address with what I was doing.

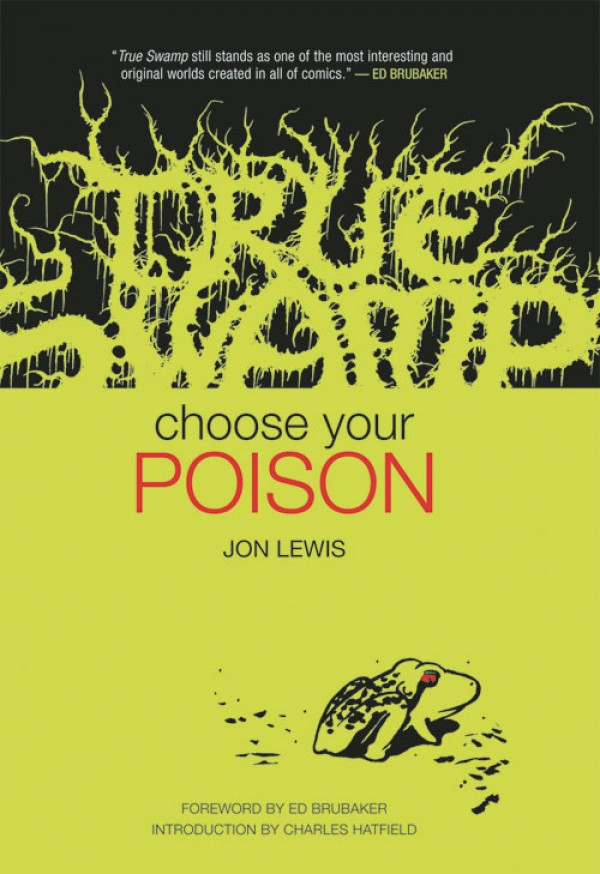

SPURGEON: Was bringing Aaron in to do the introduction your idea? I thought that was a great choice. Ed Brubaker wrote something for Jon [Lewis' book], and Charles was in there as well.

KACZYNSKI: Charles Hatfield. For Gabrielle's book, Aaron Cometbus, Gabrielle brought him -- it seemed like a no-brainer once I heard it. For Jon Lewis' book, Ed Brubaker -- I don't know if you read the actual foreword, he was basically the first reader for

True Swamp. It was kind of amazing to be able to loop that and have this book be introduced by him. Charles, I loved

his book on Jack Kirby, and he was a fan of

True Swamp. I feel like

True Swamp has been a bit of a lost book of the '90s. I wanted to have someone who was a fan of the book that could position it critically in terms of the recent history of the medium. He seemed like the perfect choice.

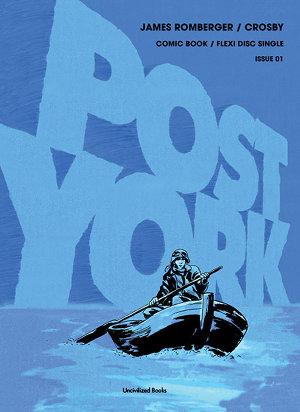

SPURGEON: Both Jon and James Romberger are kind of lost talents in a way. I don't mean that in a pejorative sense, but more that they haven't quite connected with a readership to match their talent.

SPURGEON: Both Jon and James Romberger are kind of lost talents in a way. I don't mean that in a pejorative sense, but more that they haven't quite connected with a readership to match their talent.

KACZYNSKI: I agree with you. I think James was a little bit... it seems like he was maybe in the wrong place. He's done some amazing work, but he's not very well known to the sort of audience that companies like Drawn And Quarterly or Fantagraphics or myself cultivate. He's been essentially a

DC/Vertigo kind of guy. He comes from that background a little bit. He has a pulp sensibility. But again, he's been recently converted to this, getting away from doing work for DC/Vertigo and trying out this stuff. I'm looking forward to

the Fantagraphics edition of 7 Miles A Second, which looks amazing. I just started talking to James last year at the Brooklyn Festival. He showed me this

Post York thing and it just kind of went from there. I loved

7 Miles A Second when it originally came out, and it's mystifying to me why some of these people aren't better known, or still published.

SPURGEON: Do you see a corrective impulse for your publishing, or is it fair to say that's something you like, that you can go find someone and present their work in a way that should be presented, to show their work to an audience you feel they deserve? Is that something that interests you?

KACZYNSKI: I guess that's part of the impulse. When I think back, I've always had a chip on my shoulder about comics generally. In high school I would write all sorts of essays for my English classes about comics, and trying to convince my teachers that comics are a legitimate literary medium. [laughs] There's always an impulse to redress a wrong, because they tended to dismiss this kind of work. I guess that's part of the impulse here. I'm definitely publishing other people that aren't forgotten or lost. [Spurgeon laughs] It's going to be a mix of things.

SPURGEON: Could you broadly outline your ambitions in terms of the structure of Uncivilized? Is there a certain number of books you want to do a year, a pattern you want to fall into?

KACZYNSKI: I don't want to over-extend, at least initially. There's no ambition to be a huge company. I would like to be a relatively successful small publisher -- maybe 8 to 10 books a year, maximum. Maybe some small things in between, pamphlet comics or minis. I still want to continue doing mini-comics. I feel like if I was going to sound corporate, that they're my R&D, research and development. You get to try out different techniques and different artists. It's a nice way to try out a specific aesthetic or a different artist without spending a lot of money.

SPURGEON: You mentioned talking to James at one of the Brooklyn shows; the 2012 version is where you and I talked to set up this interview. Certainly there's a lot of conventional wisdom out there that the shows and festivals have become increasingly important, that this year may be the best year of shows ever. From a publishing perspective -- or a cartoonist's perspective -- have the shows become more important, are they locking into a circuit?

KACZYNSKI: It feels that way to me. I feel like I have to be at a certain number of shows a year: to launch a book, to have something noticed or whatever. This is my first year as a publisher doing shows -- I think I did most of the shows this year.

SPURGEON: How many would that be?

KACZYNSKI: It's mostly from Fall onwards. From

CAKE, the Chicago show. Then

SPX, Brooklyn,

APE -- that's four shows for that half of the year. The first half of the year I didn't have any books. I was hunkered down, preparing for the rest of the year. I don't know. It's definitely been adding to the bottom line. The Brooklyn show was amazing. I had a really good SPX like a lot of people. Brooklyn basically matched the SPX numbers in one day for me. It was kind of amazing.

SPURGEON: What makes a good show for you, from a publishing perspective? Have you been able to figure out what the difference is now having done a few shows? Is it bottom-line sales, getting the word out, having a certain kind of book there, is there a formula for what works?

KACZYNSKI: It's still going to be a bit of trial and error with these shows. As I have more and more books, I'm going to have to figure out if I need two tables, how to bring people to shows, etc., etc. For the most part, the shows I enjoy the most, they make money at the very minimum. When the artists are around, and they're having a good time, and the show is vibrant in that I can walk around and see a lot of interesting stuff. I've been doing these shows for a very long time as a cartoonist, so all of those things you want in a show as an attendee works also for the publisher. If there's a lot of good work all around, everybody benefits. If there are a lot of new debuts, it brings in more people, and everyone benefits. Shows where it's a little bit thin on that, it's not so good.

SPURGEON: Going into 2012 there was talk that business on the alternative and arts end of comics was slowing down a bit, that we were entering solidly into a down period after a slightly crazy period of book contracts with major publishers and festival hits and the established publishers in that world -- Fantagraphics, D+Q, Top Shelf -- finding their stride in terms of exactly what it is they want to do. And now we're in a down period where it's going to be a bit more of a struggle. There's a real optimism to this wave of micro-publishing we're seeing with Uncivilized and some others. It's like you're collectively voting to stick by comics. Eight to ten books a year for a literary imprint is an ambitious plan. I assume you're optimistic about the way things are going to be three, five, ten years from now, although maybe not -- maybe you're throwing stuff against the wall. Are you optimistic generally?

SPURGEON: Going into 2012 there was talk that business on the alternative and arts end of comics was slowing down a bit, that we were entering solidly into a down period after a slightly crazy period of book contracts with major publishers and festival hits and the established publishers in that world -- Fantagraphics, D+Q, Top Shelf -- finding their stride in terms of exactly what it is they want to do. And now we're in a down period where it's going to be a bit more of a struggle. There's a real optimism to this wave of micro-publishing we're seeing with Uncivilized and some others. It's like you're collectively voting to stick by comics. Eight to ten books a year for a literary imprint is an ambitious plan. I assume you're optimistic about the way things are going to be three, five, ten years from now, although maybe not -- maybe you're throwing stuff against the wall. Are you optimistic generally?

KACZYNSKI: Yeah, I think so. [laughs] It's a mixed bag. Always. But yeah, I'm optimistic. The boom you talked about, it was a different kind of boom. Maybe Fantagraphics and Drawn And Quarterly locked into what they were doing, but it was also a boom for the big guys to get in on graphic novels. It was a weird time, because that was kind of the first time graphic novels made it into the book market and they seemed to be performing very well and everybody was like, "I need to have one" without knowing what they were doing with it. I think what's happening now is that a lot of those books didn't do well for those publishers. They did good numbers, like if you sell 20,000 of something and you're

Random House, that's peanuts, right? That's a book that's probably not making money back for them. But for a publisher like me, that's an amazing number.

So I think that space is being abandoned by the big guys, a little bit. I think there's a mid-level list of material that's good that's being abandoned on the high end of thing. I think that's why there's this surge of smaller publishers that are realizing that there are these artists that are good and are selling but there's no interest from the big guys because they kind of got burned. I think there's a little bit of an opening for the micro-publishers here. And also there is so much more good work out there. There's a lot more new talent that's actively producing work and trying to make it work for them. I don't know. There's

something going on. [laughter]

SPURGEON: One of the ways you described what you were doing was in terms of it being sustainable; it seems like there is a built-in modesty to your plans that emphasizes something achievable as opposed to shooting a rocket at the moon and seeing what happens. It sounds like you feel that what you're doing may have a longer life than tossing $140,000 advances at random books, that that probably wasn't a sustainable model.

KACZYNSKI: There is a certain amount of modesty about that. At the same time, I make sure that every project I do at least makes its money back. So there are no losses. I'm not the kind of organization where I can lose money on things. I try to design everything and promote everything that there's enough to do the next project. Maybe do something more ambitious next time. I'm trying to create a sustainable model for this thing. It's still a work in progress.

SPURGEON: I greatly enjoyed your new book. A lot of it was

SPURGEON: I greatly enjoyed your new book. A lot of it was MOME

stuff -- did everything appear in Beta-Testing

appear in MOME

?

KACZYNSKI: Pretty much all

MOME stuff except for the last story, which was brand new.

SPURGEON: I haven't talked to a lot of the cartoonists that worked for MOME

about that experience. I get the impression from people that for those cartoonists that published there, MOME

was really valuable in terms of keeping people productive and making comics and focused on producing work at a time when there wasn't a whole lot of structure out there.

KACZYNSKI: I agree with that.

MOME showed up kind of at a moment where both Drawn And Quarterly and Fantagraphics were abandoning the pamphlet model. This was the only place where a shorter piece could be published and seen by an audience, relatively quickly. There was no lag time for two or three years and working in complete obscurity for a long time. For me personally, it was amazingly valuable. I had a kick in the ass every four months to complete something. I didn't always succeed. The first four or five issues I tried to contribute something every time, and then it kind of slowed down for me a little bit.

SPURGEON: How were you drawn into that orbit? Were you recruited? Did Eric [Reynolds] track you down and talk to you? Do you know how you came to their attention?

SPURGEON: How were you drawn into that orbit? Were you recruited? Did Eric [Reynolds] track you down and talk to you? Do you know how you came to their attention?

KACZYNSKI: I'd been going to comics shows for a long time. My comics had been out there. Eric had seen my

Trans minis and liked them enough to e-mail me and say, "Hey, I like this. Whatever you do next, show them to me." I showed him a few things I did after that and at some point, he said, "Let's put that in

MOME." It kind of went from there. It wasn't like, "Do something for me." It was more like, "I like your stuff, keep sending me stuff and we'll see what happens."

SPURGEON: You said once in an interview that you got to a point where you returned to comics after being away for a while and a big chance is that you spent more time on every page, on the comics themselves, than maybe you had before. Was MOME

good for you in that you had some leeway in terms of what you could send in?

KACZYNSKI: Absolutely. You always knew you couldn't do more than 10-15 pages max, because it's an anthology. It was nice to think about comics in smaller chunks. You could focus on telling stories with a beginning and an end in 10 pages, 12 pages, and focus as much as you could on that story. You could spend a little more time with it because it was only 10 pages, or only 12 pages. It was a very valuable thing to have.

It helped me get more serious about everything, too. I was serious, but when you don't have a venue like

MOME, for whatever reason you don't think about getting better -- or it's a slower process. When you're offered that venue, you're suddenly like "People are going to see this, I need to do something more serious." I feel like for me at least that was an important motivator. I'd been doing comics for 10 years before that -- publishing mini-comics for 10 years before that, I'd been doing comics since I was eight years old. It was always a little bit like, "Yeah, I'm just self-publishing this." Race to the end so you could have a new mini-comics, cut corners a bit. For whatever reason you're not doing yourself a lot of good --

MOME gave me an opportunity to

not do that.

SPURGEON: Was appearing beside certain peers also a motivating factor, that you didn't want to be shown up?

KACZYNSKI: That was part of it. I was also in this drawing group in New York, Jon Bennett was in it and Gabrielle, Jon Lewis was in it. A few other people. That was the first time I'd seen other artists do work. That was very motivating. How much work goes into a page, how much work they did, showed me that maybe I wasn't spending enough time on my pages. You know? It kind of went from there. The first few issues of

MOME I tried to do the best pages I can, I wanted to be the most interesting story in this issue. There was a little bit of competitive impulse.

SPURGEON: A lot of the work in here is connected by the fact that they're societal critiques. You mentioned studying architecture, and the architects I know are very sensitive to the shapes of cities, city planning, infrastructure issues and the way things function and relate to one another. That's a lot of what your comics get at in terms of the quandaries they portray, this kind of fraying of societal structures. Is that an explicit interest of yours, this critique of society -- I know that you're well read, but I don't know how much of your reading is in that direction.

SPURGEON: A lot of the work in here is connected by the fact that they're societal critiques. You mentioned studying architecture, and the architects I know are very sensitive to the shapes of cities, city planning, infrastructure issues and the way things function and relate to one another. That's a lot of what your comics get at in terms of the quandaries they portray, this kind of fraying of societal structures. Is that an explicit interest of yours, this critique of society -- I know that you're well read, but I don't know how much of your reading is in that direction.

KACZYNSKI: It's a big interest. [laughs]

SPURGEON: Can you talk about how that developed? Did it come out of the interest in architecture?

KACZYNSKI: Architecture was something I got into mostly as a pragmatic major for somebody interested in art. I fell in love with the discipline, and as I got more into it I fell in love with all of the issues surrounding urban planning, infrastructure and how these things come about. Whenever you did a project of any kind, you had to do an archeology of a site. How did this site come about? Here's the original grid plan. Here's how it changed. Here's how this highway affected this area. Here's why this weird wedge of land exists. This and that. It kind of sucks you in, digging all of this stuff up about it. How there are very deliberate choices made at some point to create the situation on the ground. You just walk by it, you don't know it's something very deliberately created.

I've taken that to broader, philosophical kinds of things. The political systems that we have, the economic systems we have, someone at some point made decisions about policies that created the world we live. I want people to be aware they didn't happen willy-nilly, that a lot of these choices are deliberate and a lot of these choices can be changed. That gets reflected in the comics. With the

Trans books, they're more like philosophical tracts, whereas the

MOME stuff it's more fiction steeped in those ideas.

SPURGEON: There's an anxiety present in a lot of your stories. It seems like the kind of deliberate planning you talk about would be a comfort to a lot of people, that these things are planned. So I find the anxiousness curious. The fact that these thoughts are more arbitrary, or might reflect not-friendly impulses, is that maybe the source of the anxiety?

KACZYNSKI: I think the knowledge is comforting, but the anxiety... it's not even my anxiety but a general anxiety that in the US has been palpable since at least 9/11. There was an apocalyptic mindset. Things are falling apart. Things are coming to a head. There's a clash of civilizations going on. With the financial crisis, capitalism is cracking, and what does that all mean? I feel like I'm tapping into a little bit of that general anxiety.

Personally I'm interested in utopias as well. That's something I'm going to be more visible in my other book, the

Trans Terra book that's going to be coming out next year. There's all this anxiety, and it's very apocalyptic, and it feels like most people would prefer to see it all crumble as opposed to doing a few small things here and there to make things better. It's more of a frustration for me more than anxiety. It does come out in the comics as an anxiety. I think it's difficult to talk about. In the comics, especially the

MOME stuff, they're more literary in that I'm trying to get into the mindset of certain characters and people and how they would react to things where they don't know there's an underlying structure.

SPURGEON: Your comics are more focused on the mindset than the breakaway from the structured norm. There is a false apocalypse -- you're not as interested in seeing things fall down as exploring the mindset that believe that things are about to.

KACZYNSKI: Yeah, that's partly why the book is called

Beta-Testing The Apocalypse. [laughter] It's not the actual apocalypse. We're feeling it out. It's hard to say exactly. It's more like the anxiety of the apocalypse than the apocalypse itself. There's a whole post-apocalyptic genre, and that's something I used to be into, but I feel it's more interesting to find out how it came about. What happens before the apocalypse? Right before it. What needs to happen to society for that to happen. I don't know if you've read

Jared Diamond's work -- the scientist that wrote

Guns, Germs and Steel. He also wrote

a book about collapses of civilizations. That's another interest of mine -- ancient civilizations, and trying to imagine ourselves as a civilization that could end. How that could come about, and what mind set we'd need to get into to release and let go and let the whole thing crumble.

SPURGEON: Your work seems very rigidly structured for the most part. You stick to grids pretty strongly, two-across and three-across, and your work is rigorously captioned. What is it about the standard grid that appeals to you?

SPURGEON: Your work seems very rigidly structured for the most part. You stick to grids pretty strongly, two-across and three-across, and your work is rigorously captioned. What is it about the standard grid that appeals to you?

KACZYNSKI: I've been kind of getting away from it -- especially in the last story. But yes, I do like the grid, I think it's one of the things, one of these sort of grammatical rules of comic that just works.

Kirby used the grid religiously, occasionally breaking out into big splash pages. The grid is the sentence. Each page has a certain amount of panels, and that's how you tell a chunk of that story, in those panels. It's this invisible thing. Sometimes you can question it, but for the most part it's just the next sentence. This modular thing that follows the other. I think it's important to break out of it every now and then. The kind of thing I do doesn't question the medium of comics so much; it's more about trying to create certain rhythms in a story, and I think the grid does that well. You can switch from three to two across, sometimes you just have a two-page spread or you break out of it altogether. Sometimes you have complicated grids like in the "Cozy Apocalypse" story. It's almost the default you go back to so that all the weird stuff you do stands out. You can't be that way all the time, otherwise it becomes incoherent. It creates a rhythm and it creates a structure. It creates a flow.

SPURGEON: Are you a confident creator? Are you still feeling your way through your stories, or are you empowered when you see a blank page?

KACZYNSKI: I'm still feeling it out a little bit. There's a lot of convoluted work that goes into these things. Occasionally, like the condo building story, that came together very smoothly. It was scripted, I drew it and and I inked it and it was done. "Wow, I'm getting this." Since then it's been a lot of back and forth. I rewrite whole chunks, and rearrange pages. It gets more difficult. Now that this book is done and I'm almost done with the

Trans book, my next project is to work with process more, and come up with a way of working that a little bit more comfortable. It's more like the grid -- a structure that moves me along more efficiently.

SPURGEON: As you said, you do use formal effects, but you employ them very judiciously: a visual element that goes from panel to panel, or a sound effect that crosses a page. Are you

SPURGEON: As you said, you do use formal effects, but you employ them very judiciously: a visual element that goes from panel to panel, or a sound effect that crosses a page. Are you consciously

judicious in their employment?

KACZYNSKI: Yeah. I think the formal tricks are nice, but they almost work better when there are less of them. That's kind of my take on them. I tend to be deliberate with them. If something crosses a panel border, I want you to notice it and think about it. I've done more comics that explore the medium, that play more with formal tricks, in the past. It's more part of the repertoire now than something I'm deliberately going for.

SPURGEON: You've been making comics for a long time now. You've talked here and some other places about moments that were key in your development, like getting to be around other comics-makers and see how they approach a page. The idea of being more deliberate with individual pages -- eye-opening moments you've had along the way. Are you settled in now, or are you still sensitive to these experiences? Are you the cartoonist you're going to be for a while now? How important is it for you to consider new ways of doing things?

KACZYNSKI: I think I'm still pretty open. I just mentioned I'm looking for a new process. I really like

Dash Shaw's work. I've had a chance to peak at his process and it's really different from what I'm doing. We collaborated once on a story, and seeing how he works... it's very different than how Jon Bennett works. He's slower, he takes longer to put a page together, whereas Dash lunges forward and produces work more quickly, and he's able to come back in and rework certain things. There's an editing process that he has that I really admire. It's something that's difficult to do in comics. I'd like to work on that for myself, a process where I can able to produce work at a constant clip and also be able to edit.

When I was doing a lot of the

MOME work, what was great about it was being able to do these things, and they were so short I was able to wing it. If I had to redraw something, it was just one page. With more pages, you might not be able to do that. Having a process where you can edit is important, and I feel like that's something I've neglected. With longer pieces you need a process that will leave you alone, and feel like you're not falling backwards several steps.

*****

*

Tom Kaczynski

*

Uncivilized Books

*

Beta Testing The Apocalypse

*****

* cover to the new work from Fantagraphics

* photo by me at some show or another

* the

LA Diary mini-comic

* covers to the current works, showing off Kaczynski's praised art direction on those books

* a future book from Uncivilized

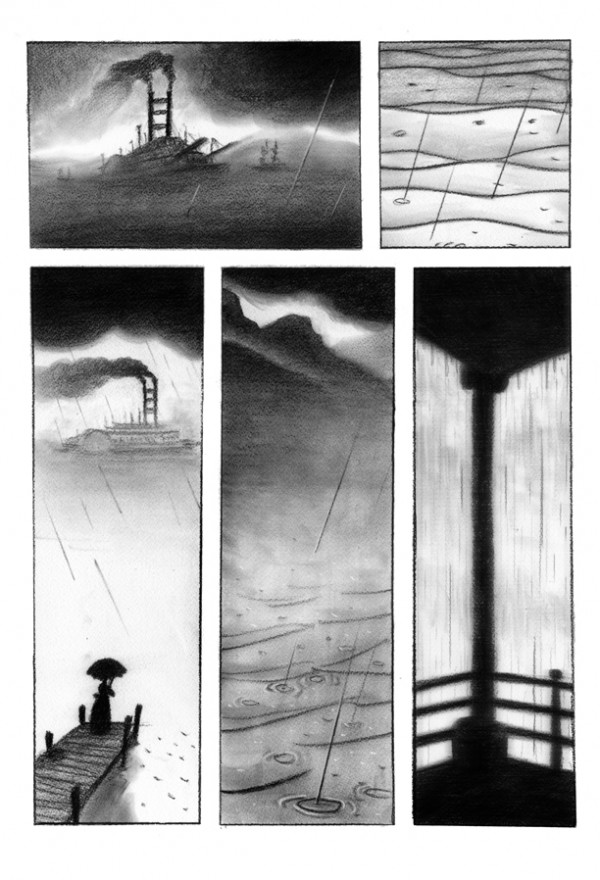

* a page from the current collection, showing society fraying if only needlessly

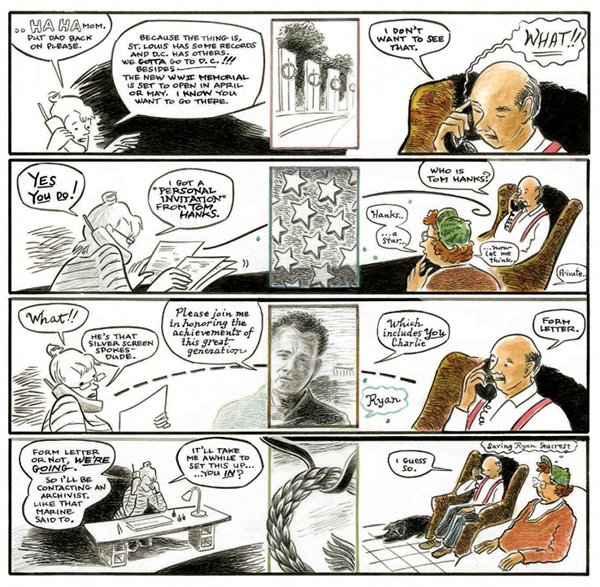

* a page from the more utopian-centered future work, provided by the artist, encompassing some of the themes discussed

* the

Trans Terra book, forthcoming

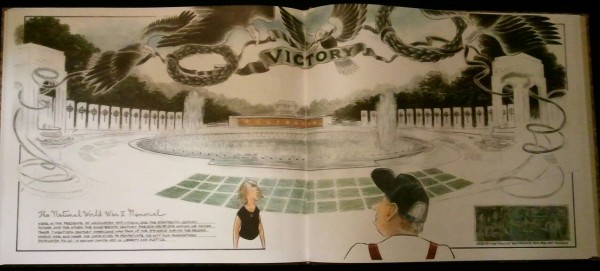

* a page with a rigid grid

* a panel that uses some formal trickery

* a snippet I liked (bottom)

*****

*****

*****

posted 4:00 am PST |

Permalink

If I Were In Tokyo, I’d Go To This

posted 3:30 am PST

posted 3:30 am PST |

Permalink

If I Were In Seattle, I’d Go To This

posted 3:30 am PST

posted 3:30 am PST |

Permalink

Go, Look: Saturday With The Seals

posted 2:00 am PST

posted 2:00 am PST |

Permalink

Random Comics News Story Round-Up

* somehow I totally missed that

a Staten Island comics shop closed in the wake of that Sandy storm from late October/early November. I know that a lot of businesses suffer this kind of thing, but I think it's a reminder that small businesses like comics shops are sort of uniquely fragile in terms of taking on too many blows like that storm caused.

* Filip Kolek talks to

Baru.

* I always appreciate that some comics entities take some time off from the incessant hype and content production at this time of year, like

D+Q and

TCJ.com. I think that kind of downtime can be important. I know that I launched the holiday interview series against a much more grand backdrop of the comics industry and the culture that surrounds it taking a break from serious discussions of

Spider-Man story content or whatever. It's something I'll consider in future years.

* not comics:

another one for the "we're old now and will be dead soon" files.

* I also missed news of

new owners for JHU, and, from even longer ago,

closure of a second location for St. Mark's.

* not comics:

kiss your bookseller.

* not comics:

Jason has been running scans of pulp covers recently.

* not comics:

an atypical image for this artist.

* finally,

Natalie Nourigat went there and back again.

posted 1:00 am PST |

Permalink

December 29, 2012

CR Holiday Interview #11—Rob Clough

CR Holiday Interview #11—Rob Clough

*****

<

posted 4:00 am PST |

Permalink

If I Were In Tokyo, I’d Go To This

posted 3:30 am PST

posted 3:30 am PST |

Permalink

Go, Look: More Billy Bounce

posted 2:00 am PST

posted 2:00 am PST |

Permalink

Random Comics News Story Round-Up

* David Brothers remembers

Barefoot Gen.

* so I guess

this is the last issue of

Moose, with extra pages and everything.

* Michael Dirda on

A Duckburg Holiday. John Kane on

a whole bunch of comics. Rob Clough on

Elfworld. Bob Temuka on

Footrot Flats. Johanna Draper Carlson on

A Wrinkle In Time. Sean Gaffney on

Blood Lad Vol. 1. J. Caleb Mozzocco on

Demon Knights Vol. 1. Paul O'Brien on

a bunch of different X-Men comics.

*

Johanna Draper Carlson picks her best of 2012.

*

it's been a long time since I've seen a post on Scott McCloud and terminology.

* Pamela Polston talks to

James Kochalka.

*

here's a list of books and comics read in 2012: always fun to see how comics folds into someone's wider reading life.

* finally, Darryl Cunningham

provides excerpts from a piece on Ayn Rand.

posted 1:00 am PST |

Permalink

December 28, 2012

CR Holiday Interview #10—Mark Siegel

CR Holiday Interview #10—Mark Siegel

Mark Siegel

Mark Siegel is the editorial director of

First Second Books, the graphic novel imprint of

Roaring Brook Press. He is also an author and illustrator whose most ambitious work to date,

Sailor Twain, came out in October of this year following an ambitious, two-year, on-line serialization. First Second creators have included

Eddie Campbell,

Lewis Trondheim,

Gene Luen Yang and a significant number of authors oriented towards all-ages graphic novels, many of whom, as we discuss below, confuse me. I always enjoy talking to Siegel at the various funnybook shows we both attend, and this year at

San Diego's Comic-Con International he seemed almost blissful about the direction of his company. I also always wanted to talk to someone who works both side of the creator/editor divide in the same calendar year. Mark indulged my curiosity about all of this and more mid-December. -- Tom Spurgeon

*****

TOM SPURGEON: I have a question for you, a potential first question, that I wanted to put up front because if it sucks I could easily fast-forward past it. [Siegel laughs] You just came off of an author's tour, an extensive one, and I have to imagine that can be a pretty strenuous thing. You also have a ton of professional responsibilities at First Second. One of the things I'm fascinated by in comics right now is how people our age -- we're near the same age -- stay in shape. Comics people aren't always known for taking care of themselves.

MARK SIEGEL: Yeah.

SPURGEON: It seems there's a mini-trend of people reinvesting in that kind of healthy living. And I wondered if that's ever been important to you, the physical fitness thing, or at least finding a way to do everything you do and maintain a healthy lifestyle.

SIEGEL: I had my own health scare about 10-12 years ago. It forced me to really devote some time to setting up a lifestyle as opposed to just wining it on whatever. As you know, that's a tough time in your life, but it's also a blessing. You basically pay some bills on how you've been living. I do try to have some sense of that. A big part of it for me, a big part of the balance of health, is having certain patterns and routines. Including creatively. I think your creative health is kind of inseparable from your physical health. For that, being able to set routines, my early morning studio stuff, and my work time, and then of course when you hit the road and do the author thing that's definitely a source of imbalance and I'm feeling, I'm definitely feeling some burnout from having scrambled some finely-tuned patterns in my life. [laughs] I'm hoping to find my way back to a certain kind of balance.

SPURGEON: Just getting the amount of work done that you get done seems to me it would take a considerable amount of thought. It's not unprecedented in comics, your kind of split responsibilities. A lot of publishing figures have also been creators. A lot of folks have found their own way into that kind of balance. Was it more difficult for you when you first started?

SIEGEL: Not really, because in a way it predated First Second. First Second came along, before that I had jobs in publishing that really were more like day jobs. First Second came along, and it's more... there's a part of it that's really dayjob in terms of the admin work, the managing side of it all. But First Second is also a baby in a creative sense? It's a project. It's a project, so it has a different kind of nourishment than just clocking in for a paycheck.

Before First Second started, I knew... when I was just a designer at