Home > CR Interviews

Home > CR Interviews CR Holiday Interview #11—Chris Mautner

posted March 22, 2012

CR Holiday Interview #11—Chris Mautner

posted March 22, 2012

I've known Chris Mautner for several years now. We shared a comics shop for a couple of years before I headed out to Seattle to edit

The Comics Journal:

Joe Miller's The Comic Store, in Lancaster, Pennsylvania. If I remember correctly, at the time Mautner had applied for the News Editor job. He wrote for me on the criticism side of things instead.

Mautner has grown immensely as a writer since, both in comics -- he's a stalwart at

Robot 6 and the on-line iteration of

TCJ -- and outside of comics, where he's settled comfortably into a staff position at a major Pennsylvania newspaper. I actually contacted Chris looking for someone to do the mainstream comics interview for this year's series, but he pointed out that other than

the New 52 coverage he did he really wasn't reading those comics. I'm happy that he agreed to switch over to this year's overview of alternative and art comics. I think he's an ideal reader for those books. -- Tom Spurgeon

******

TOM SPURGEON: Chris, I don't know that much about your reading history, particularly when it comes to non-mainstream comics. You told me that what we call alt- and art-comics make up the majority of your reading now. Has that always been the case? How did your reading develop in that direction? What are some of the titles that were important to you along the way?

CHRIS MAUTNER: You know, I can't remember a time in my life when I wasn't reading comics of one kind or another. Maybe six months when I was in sixth grade, but that's about it. I pretty much learned to read via the Sunday funnies, especially

Peanuts. The thing is, I was always a very catholic reader and never really distinguished between different genres or styles of comics. I devoured collections of the

New Yorker cartoons with as much enthusiasm as I did

Superman Family or

Amazing Spider-Man or the coffee-table sized book of

Dick Tracy strips at my local library. If it involved comics or cartoons, I was interested in it.

As a result, when

Maus came out in 1986, and the

Read Yourself Raw collection in 1987, I took an immediate interest in both books. That was probably my first exposure to the alt-comics world, though I may have read about

R. Crumb or other artists via books like

Maurice Horn's oversize encyclopedia. I remember being wowed by both books, especially

Maus. I even wrote a paper on it and

Watchmen in high school, my own version of those "Pow! Zap! Comics aren't for kids" type stories that were everywhere back then.

Even so, with the exception of

the three chunky RAW anthologies that Penguin put out, I avoided most alt or indie comics that came out around in the late '80s and early '90s, preferring mostly to stick to pre-

Vertigo books like

Sandman and

Grant Morrison's run on Doom Patrol, though I'd occasionally pick up an oddity like

Krystine Kryttre's Death Warmed Over (or the first

American Splendor collection, which I borrowed from my college library).

It wasn't until I was out of college, living on my own and attempting with a friend to publish a comics anthology that I started tracking down authors I had heard about and seen in the comics shop but had avoided for one lame reason or another -- people like the

Hernandez Brothers,

Chester Brown,

Jim Woodring and

Peter Bagge. Books like

Poison River and

I Never Liked You gobsmacked me. I already knew that comics were an art form unto themselves, capable of creating profoundly affecting work. I just wasn't aware how much good stuff was already out there being made. I was stunned by the true breadth of material being produced.

The Comics Journal was a big help in this instance. I had picked up a copy at my local

Borders (the

Neil Gaiman issue) because I thought if I was going to try to publish my own comics I needed to know more about the industry. If nothing else,

TCJ convinced me that I had no business making comics. So the comics-reading world owes you a debt of gratitude in that regard, Tom.

SPURGEON: [laughs] I think Scott Nybakken gets credit for that one. Hey, one thing about which I was potentially curious is that you're at the age where you might have read a lot of what we sometimes call indy-comics, comics that are mostly genre comics but originate outside of the Big Two. There are still some of those comics left -- like RASL, and Casanova -- but do you think I'm right in my hunch that that's not as vital a category as it was 15 years ago? Why do you think that is?

MAUTNER: Well, that depends on what you mean by the word "vital," if I can get all Bill Clinton-y on you. I think you're right in that indy comics, or what we traditionally think of as indy comics, are not as predominant or as powerful a critical or marketing force as they were in the days of

Fish Police and

Boris the Bear (or later

Bone and

Too Much Coffee Man). Those books, even the most seemingly innocuous and slight, had a slight political aspect to them simply due to the fact that they were published by folks other than

DC and

Marvel. They, especially the self-published, hardscrabble titles, had a "rebelling against the status quo" aura to them that held a lot of appeal for readers looking for comics that were outside the norm, but not too different from the norm. That might have helped them garner more notice than perhaps some of them deserved. They don't have that sort of cheat anymore and I'm not entirely sure why. Perhaps it's the result of fallout from the distributor wars? I dunno. Or maybe it's just that the signal to noise ratio is so high right now it's harder for non-superhero genre comics to get noticed.

On the other hand,

Hellboy and

BPRD are still really popular.

Chew is one of the bigger success stories in comics lately. People still really like

Walking Dead and

Invincible.

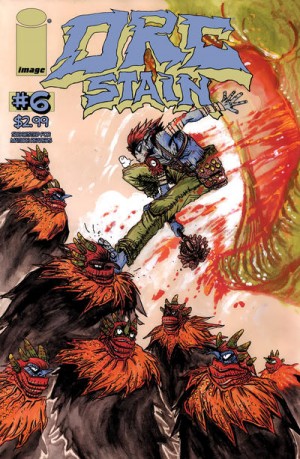

Orc Stain was pretty heavily acclaimed.

Dark Horse,

Oni and

Image don't seem to be in danger of not being able to pay their light bill, at least from my meager vantage point. I don't see as much diversity in these types of books -- they all seem to be horror or sci-fi/fantasy based and many rely on a clever hook of some kind which is useful for making a 30-second movie pitch. But a cursory glance seems to suggest there's still a steady and loyal audience for these kinds of genre comics -- titles that exist somewhere on the line between the mainstream superhero fare and

Color Engineering.

SPURGEON: I know that you're also one of the critics that currently has a family with younger -- not all the way young anymore -- children. Has that changed your orientation towards comics at all? Has seeing the comics through your kids' eyes, or maybe their lack of interest in them, altered at all the way you approach the form?

MAUTNER: That's an excellent question, because I've had both positive and negative comics experiences with my kids. My daughter Veronica, who is currently 10, is nuts about comics. She learned how to read by absconding with my copies of

Little Lulu. She's devoured

Asterix,

Tintin,

Bone (her favorite),

Peanuts,

Calvin and Hobbes, Raina Telgemeier's

Smile and most of First Second's all-ages line. She spends hours on the weekend making her own multi-chapter, epic comics and while she rarely finishes them, she blows me away with her command of visual storytelling. Obviously because I'm her dad I think anything she does is great, but I'm seriously in awe of her ability. She seems to understand the medium in an instinctive way I never did at her age. I'll have to show you some copies of her work if we get to meet up in Brooklyn.

My son, Liam, who's eight, on the other hand, couldn't care less about comics. He has repeatedly declared all comics to be "stupid." I think this is in part a reaction to his sister's love for the medium -- a way for him to differentiate himself from her. I also suspect he might have come across a panel or story that scared him at a young age and he's reluctant to dip his toe back in the water. Also, he's very stubborn and hates having anything foisted upon him, or even suggested to him. I've tried to think of ways around that -- books I could read with him or gently nudge in his direction. I know there's titles he'd love if he'd give them half a chance, but ultimately I'm not sure it's worth the battle.

I don't know if being a parent has changed my general attitude towards comics that much. I do have more of an appreciation for what makes a good children's or all-ages book as opposed to a lot of the treacly nonsense that's foisted on kids these days or (worse) the crass commercial spin-offs of material from other media. Before being a parent, I tended to critique a book solely on my own personal criteria -- i.e. what pleased me. Now I also find myself asking as I read if the book in question -- especially if it's designed for an all-ages audience -- has a broader appeal for children, probably because I'm always on the hunt for good books to pass on to Veronica.

On a practical level, having kids has made me even more acutely aware of the vulgar excesses found in most mainstream comics these days. My wife has frequently gotten mad at me for leaving certain comics that have excessively violent or sexually suggestive covers, usually from DC or Marvel, lying on a table or next to my bed. Frequently Veronica will come up to me while I'm reading, say, an issue of

Batgirl or

Justice League and ask if it's OK if she reads it, too, and it pisses me off to no end that I have to say sorry, no. It seems ridiculous that I can't share a simple superhero comic with her featuring characters that appear on the Cartoon Network, but I don't think I would be doing my job as a parent if I did. Why do I have to hide

Detective Comics from a 10-year-old?

I think I got a little off-topic there.

SPURGEON: That's okay. Can you talk a bit more about your current consumption of alt-comics? How many comics are you seeing, and where do you get them? For instance, how much of your consumption is due to freebies or being able to go to shows. How much of your consumption is handmade comics given that you live in the not-exactly-a-hotbed part of Central Pennsylvania?

SPURGEON: That's okay. Can you talk a bit more about your current consumption of alt-comics? How many comics are you seeing, and where do you get them? For instance, how much of your consumption is due to freebies or being able to go to shows. How much of your consumption is handmade comics given that you live in the not-exactly-a-hotbed part of Central Pennsylvania?

MAUTNER: My budget is really, really tight these days, so most of the comics I get are either review copies or bought at shows like

SPX or

MoCCA, where I'm allowed to go a little crazy with my cash. The rest of my comics -- let's say about 1/4 -- are bought via Amazon or my local comics store. Most of the serial comics I'm still reading --

Casanova,

The Boys -- I buy at a very small (and I mean very small) comics store that's located in my town. More and more, though, I find myself buying comics online, largely because of the discounts I can find through sites like Amazon. I frequently feel bad that I'm abandoning giving the brick and mortar stores in my area the cold shoulder, but like I said, money's tight.

As far as mini-comics or handmade comics go, you're right, I usually have to venture outside the central PA area to get them. (For some reason I rarely order them online. Am I allergic to PayPal?) Most of the shops -- and there are actually a surprisingly large number of comic shops in my area considering where I live -- are relatively indie-friendly -- especially The Comic Store in Lancaster and

Comix Connection in Camp Hill. But while they'll carry most Fanta/D&Q/Top Shelf/etc. books, mini-comics are a line they rarely cross. As a result, that's probably one of the (many) areas of comics I'm not as up on as I should be. I should note, however, that I have regularly picked up copies of

Mineshaft at Comix Connection, and they also carry back issues of

Chuck Forsman's Snake Oil, but that's mainly because he's from the area.

SPURGEON: I get to ask this every year there's an Optic Nerve. Do you miss the serial comic book? Are there talents out there that you encounter, or work that you encounter, that you wish was available to you in that form? With something like Retrofit extolling the unique virtues of that format, do you think there will ever be a revival?

MAUTNER: Do I miss the serial comic book? Honestly, not that much. Since I'm on a tight budget, I'm actually grateful that I don't have an excuse to go to the comic shop on a more regular basis. While I like the pamphlet format and think it has its benefits, I'm not wedded to it aesthetically. And there have been enough good comics coming out in recent years to keep me from mourning its passing too much. I'm happy to consume my favorite artists' work in whatever format they think best suits their material and keep them out of the ramen aisle of the supermarket. I don't really care if

Dan Clowes ever produces another issue of

Eightball again, so long as he keeps making comics.

That said, I do worry that many young cartoonists are pushing themselves straight into big-ass graphic novels (perhaps because they don't see another way of reaching an audience), before they've had the chance to develop their chops a little. There have been a number of ambitious books out in recent years that would have been great if the creators weren't so obviously unseasoned. Having a regular series -- even if it only comes out yearly -- can give you the chance to really hone your craft. I'd also like to see more creators trying their hands at short, concise stories.

I actually think we're beginning to see the start of a pamphlet revival. Not only did 2011 herald the release of a new

Optic Nerve (which, it should be noted, featured two stand-alone stories rather than the beginning of another ongoing storyline), there's also

the second issue of Ethan Rilly's Pope Hats, which was quite fabulous. More to the point, publishers like

Koyama Press,

Pigeon Press (assuming they're still around) and the aforementioned Retrofit seemed wowed by the pamphlet format and have been releasing stellar work by folks like

Michael DeForge and

Lisa Hanawalt. DeForge in particular is someone who bears watch, not only because he's such an amazing talent, but because he's someone who's garnered acclaim and attention simply by regularly publishing work in a pamphlet format, like they did back when you and I were kids.

SPURGEON: That's a great jumping-off point. If revival of the alternative pamphlet is one story for the year 2011, what are the others? Let me suggest two. When I asked you to list a certain number of alt-comics, you couldn't get anywhere near that number, you gave me a whole lot more. Is this an unprecedented period for very good comics of the non-mainstream variety? Why so many pretty good comics right now? And how many of them are actually great?

MAUTNER: Again, it depends upon what you mean by "unprecedented." I think we've been seeing excellent or at least above-average comics coming out on a consistent basis over the past decade or so. It's gotten so that while I haven't grown blase, I think I'd be more surprised by a year in which there were a paltry number of notable books than a plethora. We seem to continue to be in a growth period, at least aesthetically if not financially.

Looking in the long-view mirror, that certainly is different from how things have traditionally been. The only comparable periods might be the golden age of the comic strip in the 1920-1940s and the underground comix era of the late 1960s (though there was a lot of schlock produced in those times too). I'm not sure what why we're currently blessed with such riches. Certainly no one is getting rich off these comics. Many aren't making any money at all. While I'm no fan of the Team Comics "let's all be supportive of each other no matter what" mentality, It doesn't seem completely ridiculous to suggest there's something about the camaraderie of the small press community (found at shows like SPX for example) that creators may find encouraging and invigorating enough to continue plugging away and pushing themselves to make better comics.

We're also seeing a lot of small press publishing initiatives coming out of the woodwork. In addition to the publishers we already mentioned there's Austin English's

Domino Books,

Blaise Larimee's Gaze Books, the

Closed Caption Comics crew,

Conundrum Press,

La Mano and

Tom Kaczynski's Uncivilized Books. And let's not forget companies like

Secret Acres,

NoBrow,

Blank Slate,

Partyka. The list seems to go on and on. This sudden growth seems especially significant to me considering

the passing of Sparkplug Books founder Dylan Williams earlier this year. Obviously there's a more than good chance that some of these companies will fall by the wayside in the coming years, but I think all this shows how strong and dedicated the alt-comics and small press scene has become over the past few years. Look at how Anne Koyama has been able to nurture the careers of folks like

Dustin Harbin and Michael DeForge. Not that long ago I think there would have been doing a lot of the heavy publishing lifting themselves if they wanted to make comics.

The Internet has helped tremendously in this regard in that you no longer have to rely on your local comics shop or wait until the next big indie convention to get your hands on these comics. True, you had mail order back then, but it was still harder to find out about these comics and purchase them than it is now.

As to how many of these books are actually great, well, I think a lot of truly great work came out this year, but obviously certain books hold up better over time than others and changing cultures and just getting older can alter one's perception.

Pope Hats and

Lose #3 knocked my socks off, but my opinion of the two could easily change depending on my irascible moods or what Rilly and DeForge decide to produce next.

One thing I think we (and by we I mean readers and critics) should be careful of is confusing the subject matter with the aesthetic value of the work. Sometimes fans and critics get revved up about certain books because they deal with a "big" topic like war or illness or bad parenting and trumpet them as being exemplary merely for discussing such subjects. They aren't. A lot of them are boring in fact.

Daytripper is a good example of what I'm talking about. It clearly seeks to make some sort of grandiose statement on the fragility and wonder of life, but it's a very hollow, shallow work.

SPURGEON: A slight spin on the same subject, but I think one that ends up in an entirely different story. Jaime Hernandez's work in Love and Rockets: New Stories #4 is probably the most talked-about alt-comic story this year, which for me puts the spotlight on a bigger story -- the incredible percentage of good-to-great comics coming out from that specific generation of alt-comics cartoonists. Do you agree with me that it seems like there's an incredible number of great works out by that initial Fantagraphics/D+Q generation? Why is that generation defying the comics-history odds and staying productive and continuing to make challenging work?

SPURGEON: A slight spin on the same subject, but I think one that ends up in an entirely different story. Jaime Hernandez's work in Love and Rockets: New Stories #4 is probably the most talked-about alt-comic story this year, which for me puts the spotlight on a bigger story -- the incredible percentage of good-to-great comics coming out from that specific generation of alt-comics cartoonists. Do you agree with me that it seems like there's an incredible number of great works out by that initial Fantagraphics/D+Q generation? Why is that generation defying the comics-history odds and staying productive and continuing to make challenging work?

MAUTNER: This year in particular does seem to have resulted in an onslaught of books from that particular generation. In addition to

L&R Vol. 4, there was

Chester Brown's Paying for It, Daniel Clowes'

The Death Ray and

Mister Wonderful (older works in new packaging, but still),

The G.N.B.C.C. by Seth, the new

Optic Nerve from Tomine,

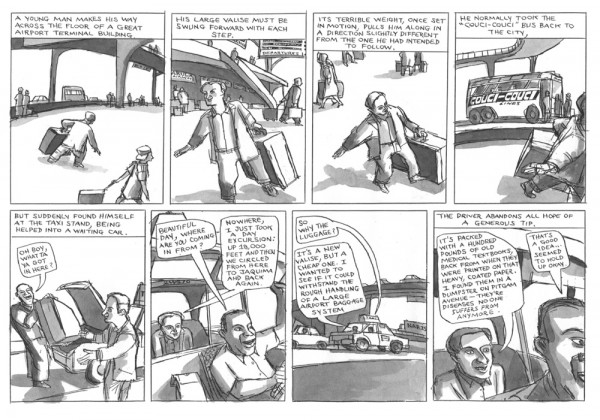

The Cardboard Valise by Ben Katchor,

Chimo,

Gilbert Hernandez's Love From the Shadows and

Jim Woodring's Congress of the Animals. I'm probably forgetting a few. Even though he's considerably younger, you could arguably throw

Craig Thompson's Habibi on that list and maybe even

Frank Miller's Holy Terror (but only if you're being extremely generous). I think one of the things that's drawing our attention is the fact that most of these authors have been laying low or working on various non-comics projects until recently. If

Joe Matt and

Chris Ware had books out this year, I think heads would have exploded.

Is it really against "comics-history odds" to be producing quality work in your middle age years? I'm not sure I agree with that idea. There are a number of underground cartoonists still out there producing great, challenging work, like

Kim Deitch, for example. Joyce Farmer's

Special Exits came out last year and she's no spring chicken. Whether you like it or hate it, Crumb's

Genesis was certainly an ambitious work.

Carol Tyler's finally getting her day in the sun and I'm really expecting Spain's upcoming

Cruisin' With the Hound collection to be pretty fantastic. More to the point, there are plenty of strip artists and other cartoonists that continued to make great work as old age approached.

Tintin in Tibet is arguably Herge's best work and that came pretty late in his life. And wasn't Barks well into middle age when he did those classic

Uncle Scrooge stories? Is it really that surprising that Jaime and his contemporaries are still making solid comics? Can you point to other cartoonists that for whatever reason haven't?

Also I think it's worth pointing out that Clowes, Woodring, Bagge and company are really the first generation of alt-cartoonists. I suppose the underground gang are technically their predecessors, but that generation was more a part of the larger counter-cultural movement of the 1960s. They didn't come out of the very narrow, specific comic shop scene the way Clowes, etc. did. So I don't think we really have a precedent for the sort of career the Hernandez Brothers and others -- creating generally non-genre, usually self-contained comics -- have built for themselves. The question to me seems to be does that group represent a very specific place and time the way the undergrounds do will we see careers like theirs reflected in the generations that have follow them? Does that make any sense? I feel like I'm being a bit vague here.

SPURGEON: Now that you've had a few months to take in those comics from Jaime, do you have a fresh perspective on what he accomplished there? I know that a lot of initial reactions, including my own, were sincere but reading them now they seem slightly -- to use a phrase from earlier in this chat -- gobsmacked. What about that work will be remembered 15-20 years from now, or will it at all? Are there any other works out this year you think are particularly built for the long-haul in terms of their overall reputation?

SPURGEON: Now that you've had a few months to take in those comics from Jaime, do you have a fresh perspective on what he accomplished there? I know that a lot of initial reactions, including my own, were sincere but reading them now they seem slightly -- to use a phrase from earlier in this chat -- gobsmacked. What about that work will be remembered 15-20 years from now, or will it at all? Are there any other works out this year you think are particularly built for the long-haul in terms of their overall reputation?

MAUTNER: Well, I actually only just read the fourth volume of

L&R the other week, so I don't know how fresh my perspective really is. I think it's pretty fantastic work of art -- gobsmacked is the absolutely correct term to use. For years now I've been thinking while perusing through my back L&R volumes or in the shower, "When will Maggie finally get a happy ending? Will she ever find some sort of peace in her life?" I really actually think these thoughts. That's how vivid a character she's become in my mind -- I think about her in the same manner I might an old college or high school friend. While certainly there's been a lot of breathless hyperbole about this book much of it seems deserved. I do think context does help in appreciating this particular story. I know I could give my wife the first half of "Love Bunglers" (i.e. Vol. 3) and she'd get it right away without any back story and think it was genius. If I gave her Vol. 4 first, I'd probably have to explain Ray and Maggie's relationship at some point, and who Letty is, etc. Whether that's a mitigating factor in evaluating the greatness of the comic is up for debate. Hernandez is very clearly in for the long haul here and has been some time and I'm not sure the fact that you might have to some familiarity with the previous stories to garner the whole "enrichment experience" is a detriment. At any rate, I'm curious to see how "Love Bunglers" will read when its two parts are collected into a whole.

But really, the comic is such a mastery of pacing, how can you not be in aw of it? Look at "Return to Me" and how Jaime completely suckers you in by having Letty talk in the present tense even though it's a flashback, just to ensure that you're completely devastated by those last two panels. And then how that incident allows one more puzzle piece of Maggie's personality to snap into place, and harkens back to her conversation with Angel. Look at Ray's facial expressions when he first sees Maggie. Look at how he's able to convey such a strong sense of place with such minimal backgrounds. If Xaime's work will be remembered at all 20 years from now -- and it seems perfectly reasonable that it will be -- they'll be talking about "Love Bunglers."

I think Jim Woodring's

Congress of the Animals makes a nice companion piece to Jaime's recent work in some respects. Both artists have spent a good deal of time building and enriching their unique universes and like "Bunglers,"

Congress is something of a game changer, as by the end Frank's world and his perception and appreciation of that world has changed considerably thanks to the arrival of a new character. In some respects I didn't like

Congress quite as much as

Weathercraft, his last graphic novel, perhaps because it didn't play up the big

Campbellian mythos as much as the latter did. All the same, it seems like a real touchstone book in the Frank oeuvre and will be discussed again and again whenever people talk about Woodring's work.

As far as other "long-haul" books, I think

Habibi is certainly the book that garnered the most anticipation and the biggest critical reception this year, most of it seemingly positive with some perhaps strong negative or at least questioning reactions. It certainly has an eye on being around in its desire to confront issues of sex, culture and religion. I think it's Thompson's strongest work to date which is not to say that I think it's entirely successful in grappling with those issues. I'm curious to see how it is regarded over time, if it becomes as influential and beloved as

Blankets has.

SPURGEON: Is there an alt-comic, or let's say up to three comics, that you don't think matched either the hype you saw upon their release or the expectations given the creator involved? What were your biggest disappointments this year as a reader and critic?

MAUTNER: I know I'm not alone in saying one of the biggest disappointments of the year was Chester Brown's

Paying for It. It had been so long since Brown's last book,

Louis Riel, that I was anxiously anticipating his new comic as I consider him to be one of the modern masters of the form, and was very much interested on his take on such a politically thorny and deeply personal issue. Sadly, the book turned out to be little more than a lengthy polemic, and polemics, even great ones, rarely make for great art. The book is hampered in so many ways -- the lengthy appendixes filled with straw-man arguments, the refusal to genuinely address certain issues, the insistence to take issues to illogical and even ridiculous ends (i.e. his "prostitution utopia"), the sudden third act revelation that comes along so curtly and quickly that the reader wonders if Brown isn't trying to sidestep the implications of that revelation, and perhaps most significantly, the manner in which he draws the women, an act of consideration and sympathy that inadvertently leads to effectively dehumanize them to little more than tits and ass. Brown's "girlfriend" may have wanted to be left out of this book as much as possible, but her omission only serves to hurtle book and Brown's argument. It doesn't help that

Paying For It has so many good scenes that remind us why Brown is such a significant author, most notably the sequences with Joe Matt and

Seth, which you highlighted in your own review.

I suppose in some respects

Habibi was a bit disappointing in only that it was ultimately unable to reconcile or provide some coherence for the thorny issues it raises, especially regarding Orientalism and sexuality. But the book is so ambitious and beautiful and has enough really successful moments that I find it hard to knock it too much.

SPURGEON: Can I draw you out a bit on how you think Craig fails in those two areas, and, if you have one, a theory as to why?

SPURGEON: Can I draw you out a bit on how you think Craig fails in those two areas, and, if you have one, a theory as to why?

MAUTNER: Ack, I knew you were going to call me out on that. I mentioned this in

the Habibi roundtable over at The Comics Journal, but the central plot of

Habibi is essentially that of a classic romance story: two lovers, joined together in youth, torn apart by fate, go through individual travails and troubles before being reunited. Seen from that angle, it's tempting to regard the ugly abuse Dodola and Zam face as simply melodramatic obstacles designed to be overcome rather than horrible, life-altering traumas (notice, for example, how all the villains are mustache-twirling types). The stark ugliness of the dangers they face -- slavery, rape, castration -- just raises the stakes and makes the reader long for the couple's eventual reconciliation all the more. Rob Clough in his review called it "overstocking the deck," which is accurate I think, and troubling, given the unsettling (to put it mildly) nature of the type of sexual abuse Dodola and Zam undergo.

Then there's the issue of Orientalist tropes and myths that Thompson utilizes it in the book. I don't think I can do a better job discussing it than Nadim Damluji did at the

Hooded Utilitarian so

I'll just refer you to that essay. To put it simply, Thompson consciously deals with a lot of loaded symbols and archetypes in

Habibi, and I'm not sure he ever fully confronts the dark, colonial, racist origins of these elements fully, lest they spoil the fantasy he is attempting to craft. I think he is very self-aware, mind you, he's not utilizing these tropes thoughtlessly, but I don't feel he's ever really satisfactorily comes to terms with them, either.

SPURGEON: In the 1980s, reprints and translations played a role in terms of the development of art comics by providing a continuity along which the new comics could be presented and enabled cartoonists to see and be inspired by work that had faded from view. I know that you're a fan of some of those books that came out this year. Can you talk about one or two such works that really hit you, and can you suggest how they fit into the overall arts/alt landscape. I know that one writer has suggested that reprints may seem more appropriate than ever right now because so many of the great cartoonists are working in those traditions.

SPURGEON: In the 1980s, reprints and translations played a role in terms of the development of art comics by providing a continuity along which the new comics could be presented and enabled cartoonists to see and be inspired by work that had faded from view. I know that you're a fan of some of those books that came out this year. Can you talk about one or two such works that really hit you, and can you suggest how they fit into the overall arts/alt landscape. I know that one writer has suggested that reprints may seem more appropriate than ever right now because so many of the great cartoonists are working in those traditions.

MAUTNER: Two of my favorite books of this year were

Garden and

Color Engineering by

Yuichi Yokoyama. One of the things that I really find striking about them is how far apart they stand from the current comics landscape, whether you're talking about the mainstream, small press or manga. Yokoyama's interest in pure motion and perception is almost clinical -- he removes all plot and character and in

Color Engineering he almost moves to abstract forms entirely -- but not only are his comics engaging, they're exciting! I seriously thrilled to see what new, odd structure lay over the next hill in

Garden and how the cast was going to traverse it. His work is all about navigation, which sounds utterly boring and befuddling, but it's surprisingly direct and easy to grasp.

Last Gasp put out

Winshluss' Pinocchio earlier this year, and I was pretty floored by that book as well. It's very old school in some respects, most notably the jokes about sex, drugs, poop, the clergy and the military/political establishment that keeps you down, man. The kind of stuff that have dominated indie and underground comics for seeming years now. Even the whole "lets ugly up a classic children's fable" seems a bit rote at this point. All that being said, the book is just so masterfully done -- Winshluss' timing is pitch perfect -- that none of that really bothered me. I just enjoyed the hell out of it.

It is interesting to me to see how contemporary artists are adopting and absorbing the styles of past generations based on the glut of reprint projects out now. Chris Ware and Joe Matt revere

Frank King, help get those D&Q books out and now we see tons of

Gasoline Alley-influence comics. It does amaze me that so many great cartoonists are being rediscovered. I seriously never thought I'd live to see the day when a decent

Carl Barks or

Floyd Gottfredson reprint project arrived. To get both those books this year, and also

Pogo,

Buz Sawyer and not one but two books about

Alex Toth and an

Incal collection makes my jaw slacken. And also worry I bit I suppose at how long this sort of reprint boom can sustain itself.

SPURGEON: What's the strongest work you read this year by a cartoonist younger than, say, Adrian?

MAUTNER: Is Tomine that young anymore? He's in his mid-30s at least by this point, right? (checks Wikipedia) Yeah he's 37. I think if we're talking "young cartoonists" we need to newer enplane than someone who's only four years younger than me.

Maybe [Kevin] Huizenga?

But if we are talking "young cartoonists," then Michael DeForge is the person that comes to mind first. I think Tucker Stone

hit the nail on the head the other day when he wrote that the most amazing thing about how DeForge is how you can't quite put your finger on his influence and that he seems capable of just about any type of narrative. The story that makes up the bulk of

Lose #3 is very different in tone from the creepy-skeevy-riffing-on-strips stuff he had done in previous comics or even from some of the other stories in the same issue. He seemed to come fully assured and producing stellar stuff right out of the gate and just keeps getting better with subsequent comics. The "Kid Mafia" and "Open Country" minis by him I picked up at BCGF suggest a restless, confident cartoonist eager to keep branching out and trying new genres. I continue to be amazed at how talented this guy is.

I get a similar vibe off of

Jonny Negron, an artist who I heard nothing about prior to this year, and mainly discovered thanks to the constant blogging of folks like

Sean Collins and

Ryan Sands. Negron was everywhere at BCGF this year -- the new Studygroup magazine, the

Thickness anthology and his own anthology,

Chameleon. Though his work tends to lean more towards erotica, like DeForge, Negron possesses the power to create disquieting, disturbing images. I was really taken with his piece in the second issue of

Chameleon, a "Final Fight"-style ode where he used ghost-like repeated figures to suggest motion and violence. He's probably the most striking new talent I've seen this year after DeForge.

SPURGEON: You mentioned Kim Deitch, who's an astonishing artist, and I wondered if like me you've given any thought to the age of the underground guys and what that means in terms of how you've grown to think about their overall legacy. My hunch is that we have a developed sense of their cultural contribution and a slightly undercooked impression of their artistic achievements. Can you talk for a little bit about who you think the greatest artists of that generation are -- just one or two of your favorites? Have they been given their full due?

MAUTNER: I'd have to go with the obvious choice and say the two greatest cartoonists of that generation are Robert Crumb and Art Spiegelman, both of whom, I think it's fair to say, have been given their full due. Both were game-changers in terms of altering how the public perceived the medium and being a profound influence on successive generations. It might seem a tad lazy for me to so willingly go along with the canon, but their works have had a profound influence on me. Certainly Crumb continues to be one of my all-time favorite artists and I find myself returning to his work again and again.

Getting into the larger point of your question, however, I think you're right about people tending to regard the underground generation as a whole lump sum and ignoring individual cartoonists. I think Deitch has a certain critical cachet, but you could make the case that Spain,

Gilbert Shelton and others don't. Once you get past the

Zap crew, there's a plethora of underground cartoonists that have been unfairly neglected. That's starting to change, however slightly as publishers and critics start to slowly re-evaluate the contributions of Crumb and

Spiegelman's peers. There was that

Rand Holmes book Fantagraphics put out in 2010, and their attempts to re-release

Jack Jackson's work, as well as

the upcoming complete Zap Comix collection. Even

Richard Corben is going through something of a re-appreciation with his recent work on

Hellboy.

But as far as my own personal favorites go, after Crumb and Spiegelman it's a bit harder to pin down. We already mentioned Deitch, but I'll pick up and read anything he puts out; he's a consummate world-builder. I love

Spain's work, especially his autobiographical stories; I like his clean, angular style and how well it seems to fit the tone of the odd young adult stories he relates. I've also got a fondness for

Skip Williamson, I think he's something of an underrated satirist. His targets tend to be obvious ones -- the military, the government, etc. -- but he goes all in with a savagery that a bit unique among his generation, I think. Some of those stories he did for

Zero Zero were phenomenal.

SPURGEON: I wanted to run a few impressions by you that I saw expressed vis-a-vis the Brooklyn comics festival. The first is a classic, that alt-comics has an arty, pretentious thrust that fails to appreciate its humor cartoonists and their more proletarian appeal. The second is that our social media culture has made us a community of artists and writers satisfied to receive the praise of a circle of friends, and that this has stunted a lot of artists' growth. The third is that despite the rapid growth in quality works, we still don't have enough excellent works, works that don't need to be specifically contextualized, to foster a greater appreciation of the medium. Do you agree with any of those thoughts? Disagree?

SPURGEON: I wanted to run a few impressions by you that I saw expressed vis-a-vis the Brooklyn comics festival. The first is a classic, that alt-comics has an arty, pretentious thrust that fails to appreciate its humor cartoonists and their more proletarian appeal. The second is that our social media culture has made us a community of artists and writers satisfied to receive the praise of a circle of friends, and that this has stunted a lot of artists' growth. The third is that despite the rapid growth in quality works, we still don't have enough excellent works, works that don't need to be specifically contextualized, to foster a greater appreciation of the medium. Do you agree with any of those thoughts? Disagree?

MAUTNER: Regarding the first: Well, I think we've talked about this before, it's the old "comedies never win an Oscar" thing and I think it remains true to an extent. Did

Johnny Ryan's critical cachet, for instance, go up once he started doing

Prison Pit because

Prison Pit was a considerable aesthetic step up for him (and it was) or because it's a more serious -- if heavily genre-based -- work? And has the series received less than its full due because it's so firmly entrenched in certain "low" genres? Certainly we do seem to have a lack of pure humor cartoonists at the moment.

Michael Kupperman and

Sam Henderson are the only ones that come to mind at the moment (Peter Bagge publishes too infrequently these days). The cartoonists that are appreciated and do use humor -- again, DeForge is a good example -- tend to combine it with horror or other elements to mitigate the laughter somewhat.

I think the general reading public tends to favor books that have serious, literary content. There's still a stigma attached to enjoying comics and readers that aren't serious comics fans don't want to be seen reading something "silly" or "edgy" anymore than Academy voters don't want to reward, say, a film like

Bridesmaids, regardless of how well crafted and satisfying an film it might be. It's a middle-class prejudice that's very tough to break. I think as you get closer to the serious alt-comics fans, you see less of a snobbery towards that sort of thing.

In fact, more than ever, I see cartoonists experimenting with traditionally low genres, like fantasy, horror and now sex. In addition to

the Thickness anthologies there were a couple of other recent comics that dealt exclusively with sex, like

Julia Gfrorer's Flesh and Bone. If alt-comics does have an arty, pretentious thrust, I don't think it's coming from the people making the comics.

As to your second point, well comics is a very small community -- a fraction of the population reads mainstream superhero comics and an even smaller fraction reads alt-comics, so it's not surprising that like-minded folks would seek each other out and want each other's approval. There is a danger with cartoonists forming a closed-off, self-congratulating circle and it's something I think artists and critics will to legitimately watch out for, though I'm not sure it poses a serious threat yet. I honestly can't think of any cartoonists whose work has been stunted because they're only seeking the praise of their small enclave of friends. If anything would stunt an artist's growth it's by solely draw upon comics for influences and inspiration and not seeking out other forms of art and literature. Is that what you meant?

As for your third question, it is one of the great tragedies of the medium that those who love it have to constantly mitigate their enjoyment of it, holding the superior, worthy elements close to our breast and forgiving or ignoring the less savory aspects. Did you read

that Setting the Standard Alex Toth book that Fantagraphics put out? Pages and pages of lovely, vibrant art, holding up dreadful schlock. Too much of comics -- whether you're talking superhero books, comic strips, Golden Age stuff or alt-comics -- has been like that, where you find yourself saying things like "well, the plot is hackneyed, but the art is amazing" or "the guy can't draw decent 3-point perspective, but the ideas the writer is expressing is great." We're too forgiving of the junk, myself included, in praising the worthy.

Having said all that, I do think there's been enough all-around quality comics in the past ten years that we really should stop worrying about whether we've built enough of a canon to garner respect from whomever we're trying to garner respect from. I guess that's the central question, who are we trying to foster his appreciation for? Academia? The general public? My mother-in-law? Those are very, very different audiences with their own set of prejudices. A mainstream audience is going to be more drawn to pap, "respectable" graphic novels that traffic in serious subject matters but are shallow in artistry and delivery than truly challenging material.

Comics is such a fractured audience it can often seem like there's not enough good stuff out there. If you pull back, however, and take in breadth of material that's been done in comic strips, editorial cartoons, manga, european comics, alt-comics, and even superheroes, you can see a healthy pile of A+ material.

SPURGEON: Has the rise of more cartooning schools and courses in same changed the way the art form is perceived and practiced?

SPURGEON: Has the rise of more cartooning schools and courses in same changed the way the art form is perceived and practiced?

MAUTNER: Yes. Certainly the rise of "comics lit" classes in liberal arts colleges have helped foster the sort of appreciation you were discussing in your last question.

I know a professor who teaches a comics as literature class at

Dickinson named

David Ball. He's been kind enough to let me sit in on a class or two and I've seen first-hand how classes like that have raised awareness and an appreciation in young students for the art form.

But you're probably talking more about schools like

CCS and

SCAD. I do think these programs are good in developing cartoonists in that they expose them to a wider breadth of work and ideas that would typically take a much longer period of time for them to absorb. In the old days an aspiring cartoonist would only have their own collection and whatever they could dig though the back boxes of their local store to learn from past masters. It think that's at least part of the reason why you're seeing creators like

Joe Lambert and

Chuck Forsman make such considerable strides in their work so quickly. I do worry for all these artist financially a bit, especially if the marketplace shrinks any further and they're all going to be competing against each other for the potential readers dollar even more than they already are.

SPURGEON: Finally, can you recommend one piece of criticism you wrote this year, and one piece that someone else wrote?

SPURGEON: Finally, can you recommend one piece of criticism you wrote this year, and one piece that someone else wrote?

MAUTNER: As much as I hate to toot my own horn (and I really do) I was rather happy with

a review I wrote of A Single Match by Oji Suzuki over at TCJ. It was a difficult book to describe, much less take apart, and I felt like I did a OK job explaining the style of the work and whether it was successful or not.

In a similar vein, I was fortunate enough to do a number of interviews with notable cartoonists this year, but

the one I did with Gilbert Hernandez may be my favorite, but only because he was so open and honest in talking about his feelings regarding his comics and the industry at large.

As far as something someone else wrote, it probably counts more as journalism than criticism, but I was really, really grateful for Matthias Wivel's

two-

part examination of what happened to

L'Association. He did a fantastic job breaking down the players, what happened when and why it matters. It's the kind of in-depth writing I'd like to see more of regarding various North American publishers.

But if that's not criticism-y enough I'll throw in

that great essay Tim Kreider did on Cerebus in The Comics Journal #301. That was a nice bit of writing.

*****

*

Chris Mautner at Robot 6

*

Chris Mautner at The Comics Journal

*****

* photo of Chris Mautner at BCGF 2011 by me

*

Death Warmed Over, an oddity for young Mr. Mautner

* people still like

Orc Stain

*

Casanova, one of the few titles Mautner follows as a serial comic book

*

Lose, perhaps part of a new interest in serial alt-comics

* Ben Katchor, one of the many veterans of Alt-Comics Generation One that had formidable work out this year

* Jaime Hernandez in

Love & Rockets: New Stories #4

* Jim Woodring's

Congress Of The Animals

* Craig Thompson's

Habibi

*

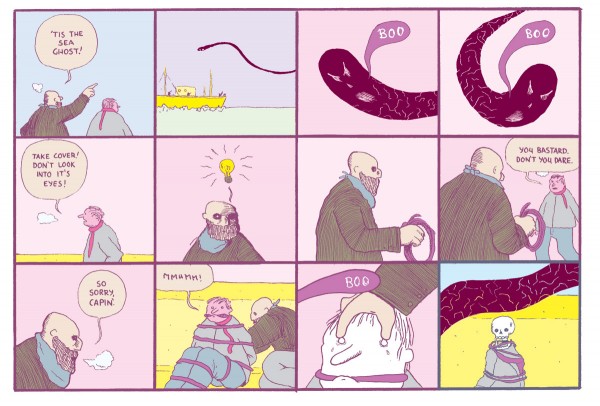

Color Engineering

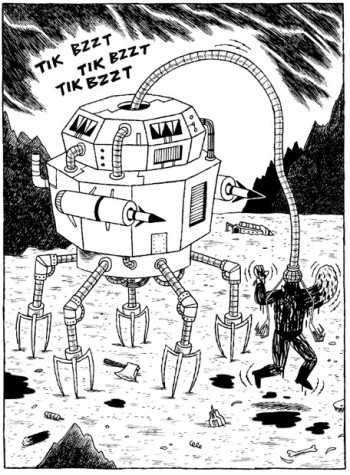

* work from Jonny Negron

* Jack Jackson, an under-appreciated underground comix cartoonist

* Johnny Ryan's

Prison Pit

* Chuck Forsman colored by Joseph Lambert

* from Oji Suzuki's

A Single Match

* Gilbert Hernandez work in 2011 (below)

*****

*****

*****