Home > CR Interviews

Home > CR Interviews CR Holiday Interview #12—Todd DePastino

posted March 22, 2012

CR Holiday Interview #12—Todd DePastino

posted March 22, 2012

I've been dying to interview

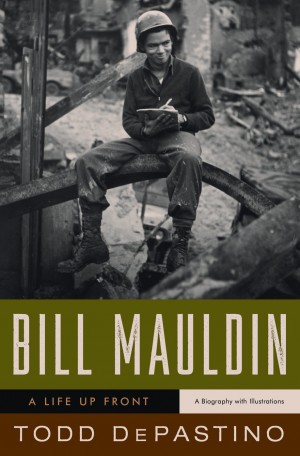

Todd DePastino since the publication of his Bill Mauldin biography

Bill Mauldin: A Life Up Front and Fantagraphics' release -- with the writer's involvement -- of the complete wartime Willie and Joe cartoons in

Willie & Joe: The WWII Years. I think

Bill Mauldin, while a deeply flawed man, was not just an important figure in comics and 20th Century American history, but about as good a role model as there's ever been for a cartoonist -- a role-model for an artist of any kind, really. Mauldin valued his craft, he told the truth as he saw it, and he aimed that truth against those that exploited the common good -- no matter what it cost him.

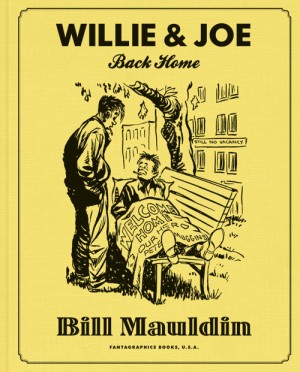

This year's publication of

Willie & Joe: Back Home details Mauldin's astonishing post-World War II run as a nationally syndicated cartoonist. As DePastino describes, Mauldin suffered greatly the effects of the War. This made the young, legitimately famous cartoonist even more sensitive than usual to the various injustices and acts of political acting out that riddled U.S. society in a time of long-awaited peace and relative prosperity. Mauldin refused to be silent about what he felt was happening all around him, despite everything to gain by making a comic strip more in tune with the ebullient parts of the national mood. The overall effect is watching someone slowly set himself on fire. It's one of my three favorite comics-related books from 2011, and, I think, one of the year's best. -- Tom Spurgeon

*****

TOM SPURGEON: Todd, I don't know the exact provenance of the Bill Maudlin work you've been doing, and it doesn't all the way connect with the other writing you've done. Do you have a personal history with Mauldin? What was your entry point into Maudlin in his life -- was he a cultural figure for you, a cartoonist, a celebrity, a veteran for you first and foremost?

TODD DePASTINO: I had only the dimmest awareness of Bill Mauldin until about a year before I started writing his biography. Someone mentioned his work to me as I was working on my first book on the history of homelessness (

Citizen Hobo: How a Century of Homelessness Shaped America). That book focused on the huge counterculture of homeless men (tramps and hoboes) that thrived in this country between the end of the Civil War and World War II. Government officials and social workers wrung their hands over this counterculture because hoboes were non-domestic men who seemed to live without the nurturing presence of women and families. During WWII, I discovered, those same officials began worrying that GIs going into the army would become non-domestic like hoboes. Bill Mauldin's

Willie and Joe were as non-domestic as could be, and they illustrated perfectly the connections between the hobo jungle and the GI bivouac of WWII. In fact, I saw that Mauldin pretty much copied the ubiquitous "Weary Willie" of the funny papers and put him in olive drab. So, I came to Mauldin as a scholar of American cultural history, not a WWII buff or comics aficionado or a fan. My interest in Mauldin was strictly business. Nothing personal.

Then, I read Mauldin's

Up Front. I borrowed an old yellowed copy from 1945. I was stunned by what I saw: edgy cartoons, rendered in exquisite detail. The humor was fresh and the draftsmanship rough-hewn in a way that you could almost feel the mud sucking at the soles of the characters' boots. Mauldin's work revealed a whole side to World War II with which I hadn't been familiar: the everyday lives of army infantry combat soldiers, not men who had volunteered for elite units -- the paratroopers, Marines, flyboys, and the like -- but the drafted warriors from hard-scrabble backgrounds with no enthusiasm for the fight, nor reverence for authority.

I tried to find some scholarly study -- or any study -- of Mauldin and came up with virtually nothing but passing mentions of him in histories of WWII. Why hadn't anyone really studied him? These WWII cartoons seemed to me to represent some of the most important popular art of 20th Century America. It was a nice discovery, untilled soil, and I thought I would write a scholarly article about Mauldin's wartime work and career. But the more I learned about Mauldin -- his adventurous and charismatic life, his mercurial character and tendency to crash and burn before rising again from the ashes -- the more fascinated I became with him. He deserved his own full-scale biography. I felt it important to get his story out and to satisfy my own fascination and curiosity. That decision to write Mauldin's biography changed my life in ways I never could have imagined.

SPURGEON: Can you talk about entering into your work with Mauldin from the standpoint of a writer preparing to do a biography? I know that for a lot of writers, doing a biography depends on there being some sort of angle not explore, or resource untapped, or someone willing to speak that wasn't before. What was your expectation going in in terms of what you could add to the broader understanding of the man and his times? How challenging was the archival work you had to do in order to write about Mauldin? What was the shape and status of what existed out there with his name on it?

SPURGEON: Can you talk about entering into your work with Mauldin from the standpoint of a writer preparing to do a biography? I know that for a lot of writers, doing a biography depends on there being some sort of angle not explore, or resource untapped, or someone willing to speak that wasn't before. What was your expectation going in in terms of what you could add to the broader understanding of the man and his times? How challenging was the archival work you had to do in order to write about Mauldin? What was the shape and status of what existed out there with his name on it?

DePASTINO: I had a relatively easy time of it as a biographer. It was a first biography, so I wasn't competing against an established interpretation. There were ample archival sources in the Library of Congress and elsewhere. The family was extremely cooperative and helpful. And I had a set of fascinating questions, beginning with these two: what drove Mauldin and his work and why did they fade into relative obscurity in the decades after WWII? Those questions inspired the early stages of my research especially.

Having said that, there were challenges. Mauldin wrote about himself a lot, but he didn't address his demons. They needed to be teased out of the material. A biographer requires an intimate understanding of the subject, but the subject always resists it. I had a recurring dream while I was working on the book. I'd be sitting in a room with Bill -- always a 1950s Bill Mauldin -- asking him questions. He'd smoke a cigarette and say nothing. And he always had a smirk on his face. He enjoyed seeing me struggle to understand him. In the end, who can define a life? You can only render it as faithfully as you can.

SPURGEON: Do you think you've succeeded in altering the perception that people have of the man? Despite the lack of a quality biography, he's not exactly an unknown figure. Is there something you hope more than others that people take away in terms of what he's about, what he accomplished?

DePASTINO: Mauldin had a 50-year career, but he'll always be remembered his WWII cartoons. Those cartoons changed the way we viewed war and the men who fight it. They utterly transformed what historian

Andrew J. Huebner calls the "Warrior Image" in America. That image involves a certain nobility, but also a touch of victimhood. Willie and Joe are victims of brutalizing forces beyond their control, yet they endure with dignity and humor. The reason the War Department allowed this new image was because the old romantic image of brave warriors eagerly inviting combat had become untenable in the pulverizing and dehumanizing warfare of the era. Americans had a barely articulated yearning for some flash of truth, some public acknowledgement of the searing horrors of modern warfare. Mauldin gave them that flash with a redemptive touch of Willie and Joe's enduring humanity. He gave Americans what

John Steinbeck and

Woody Guthrie gave them in the Great Depression: a redemptive national story about characters surviving in an unforgiving environment.

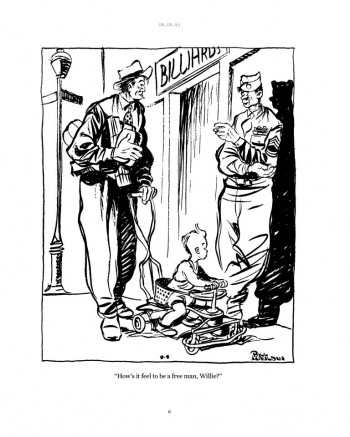

I would also urge readers to appreciate Mauldin's brilliant postwar cartoons, especially those he did between 1945-1948. One critic of my biography said that Mauldin's only great work was his wartime stuff, and therefore only two-thirds of my book is really worthwhile. Mauldin's immediate postwar work is to me just as compelling. This work -- captured in the recent

Willie & Joe: Back Home, which I edited -- is full of that

film noir and

film gris sense of isolation and confusion, betrayal and disillusion.

Going through Mauldin's cartoons from June 1945 to January 1949 (when he retired -- for the first time -- from cartooning) is like watching a wonderful

film noir serial with a hero (the older and wiser Willie appears more often than Joe after the war) who stands in the shadows, not knowing whom to trust, longing for understanding and sympathy. These cartoons reflect Mauldin's own postwar frustrations and troubles, his disillusionment and vulnerability. They also trace the nation's descent from the idealism brought about by Victory to the fear and paranoia of an emerging Cold War. World War II had radicalized Mauldin, thrusting him into the struggle to raise a better world out of the catastrophe to which he had been witness. He campaigned for civil rights especially. But these efforts only brought him grief. His syndicate censored his cartoons, and the FBI started investigating him, even trailing him on some of his trips to military bases. His growing paranoia was in many ways well-founded, and the drama of his life -- his divorce, his fall from popularity -- is all captured in the wonderful body of work he did before his first retirement.

SPURGEON: Do you have any perception of what the audience has been for the work you've been doing with Mauldin? He was a well-known figure to a lot of people of my father's generation, and of course to those that fought in World War 2. I don't know that the same folks that bought Mauldin's books are buying this one, just from the viewpoint that I'm not sure there are as many of those folks left around. What do you think a younger reader takes away from learning about Mauldin?

DePASTINO: The audience for my Mauldin biography skews older, for sure. My agent got a dozen rejections from young editors, which all said the same thing: "What a fascinating life and work. But I've never heard of Mauldin, and our readers won't have heard of him either. We'll pass." Finally, we found an editor in his 70s at

W.W. Norton who all but exclaimed, "I can't believe there hasn't been a bio of this guy."

The morning my book came out -- that very morning -- I got a call from a man named Sol Gross. He was a GI in WWII who'd been captured during the Battle of the Bulge. He called to thank me for writing the book. He hadn't read it yet, but he was calling me to thank me. As he was thanking me, he began sobbing. His wife took the phone. Mrs. Gross told me that after arriving at Stalag 7B, Sol watched as German guards began selecting Jewish-American prisoners for transport to

Berga, a subcamp of

Buchenwald. Sol quaked as a nasty-looking guard approached him and roughly pulled out his dogtags, which had an "H" stamped on them for "Hebrew." The German lifted the tags over Sol's head and replaced them with those of a GI who had died in Sol's barracks the night before. The guard left without saying a word. Sol looked down at the new tags inscribed with the dead man's name and, at the bottom right, a "P" for Protestant. He never saw that guard again.

I would go out and give book talks. Most of the people who showed were WWII veterans. They'd bring their scrapbooks and tell me their stories. They were the real Willies and Joes. They would shake my hand and tell me how much Mauldin meant to them and thank me for writing the book. One man shook with his left hand because he had no right arm. It had been blown off at Anzio.

I can't tell you how transforming this experience was for me. Before writing the biography, I hadn't really understood what military service, much less combat, was all about. I knew intellectually that combat was scary and life-threatening. But I didn't really understand just how brutalizing, degrading, humiliating, terrifying, and dehumanizing it was. I'm ashamed to say I didn't appreciate what these men really went through at such a young age and then somehow lived the rest of their lives with that trauma.

I eventually quit academia and started a non-profit called the Veterans Breakfast Club which creates public forums for veterans to share their stories of service with the public. Our storytelling breakfast last week drew 200 people, and we heard from World War II, Vietnam, and Afghanistan veterans. I want non-veterans like me to understand what it means to live through that trauma and endure the rest of life with the kind of dignity and nobility that Willie and Joe embodied. Mauldin really got it right. I'm reminded of that daily with the men and women of the Veterans Breakfast Club.

Here's a recent article I wrote about the Veterans Breakfast Club.

SPURGEON: Todd, I'd like to talk a bit more about those late 1940s cartoons, because I was blown away by how smart and cynical and insightful they were. I was also struck by the self-immolation that was going on, that fact that he was taking a sledgehammer to the kneecap of a potentially lucrative career. How much do you think what Mauldin was doing was coming from a position of absolute clarity and how much do you think what he was doing was an emotional response from all that he saw that distressed him? Is it even possible to separate those things?

SPURGEON: Todd, I'd like to talk a bit more about those late 1940s cartoons, because I was blown away by how smart and cynical and insightful they were. I was also struck by the self-immolation that was going on, that fact that he was taking a sledgehammer to the kneecap of a potentially lucrative career. How much do you think what Mauldin was doing was coming from a position of absolute clarity and how much do you think what he was doing was an emotional response from all that he saw that distressed him? Is it even possible to separate those things?

DePASTINO: I've always seen Mauldin's late 1940s cartoons as masterpieces on the level of his World War II work. One might even make the argument that they're more impressive in some ways because they cover such a wide swath of events and experiences, whereas the World War II work focuses on the infantry's frontlines.

When I look at these cartoons, I think of literary critic

Dominic LaCapra's claim that some books are good to think about and a very few are good to think with. Mauldin's postwar cartoons are good to think with. They not only provide a window to the times, like, say, good photographs or reporting might, but they also raise fundamental questions and issues that are with us still. How much privacy should we give up in exchange for security? What does democracy really mean in a society riddled with inequality? Can we really claim to be free if we shut our golden door to immigrants? Is it justified to support a dictator abroad if it furthers our national interests? These are just some of the questions that Mauldin raised time and again between 1945-1948. His cartoons operated on a level that no one else's did, with the possible exception of

Herblock.

As for whether Mauldin was given some kind of clarity at age 23 or simply reacted emotionally to the world around him, I'm fairly certain these two qualities weren't mutually exclusive in his case. Mauldin was an emotional thinker. He had strong and clear opinions, but even when he was uncertain about his position on an issue, he could lay out the opposing sides in such a way as to clarify the debate and bring it back to the real stakes.

There are two things about Mauldin in 1945-1946 that few people know and should be remembered. First, World War II was traumatizing for him. He saw a lot of combat. He saw a lot of fine young men killed and whole towns and cities leveled. He came home unsure if the catastrophe was worth it, was justifiable. But he didn't have any time off. He kept on cartooning even as he was dealing with his readjustment to civilian life. The second thing to keep in mind was his brief flirtation with the Left. He spoke out in several venues and for several causes, like Civil Rights, where the leading activists involved were Communists. This was a formative experience for him, and it brought him a lot of grief from his editors and readers.

SPURGEON: Some of Mauldin's fans and peers had to figure out what he was doing, even if they thought what he was doing was wrongheaded. Newspaper cartoonists can be very small-c conservative in terms of how other cartoonists treat their business. Do you have any sense of what the reaction was to what Mauldin did in that late '40s run? Did he have other cartoonist friends?

DePASTINO: This is a wonderful question, Tom, and I wish I could answer it, but I just don't know enough about what other cartoonists thought about his work in 1945-1946 to answer it.

SPURGEON: How easy was it to find those comics? You ran some of the comics that looked like they had been worked on.

SPURGEON: How easy was it to find those comics? You ran some of the comics that looked like they had been worked on.

DePASTINO: It wasn't easy to find all the comics. Mauldin collected some of them for his 1947 book

Back Home, and the book contains good copies of those. Others came from the original drawings in the Library of Congress's Print and Photographs Division. I know

Gary Groth at

Fantagraphics somehow got his hands on

United Features coated-stock proofs for many of the cartoons. A handful of others had to come from microfilm copies of newspapers. Microfilm was intended to preserve the words, not the images, so there's often a deterioration of quality when you grab images from microfilm. But I'm astounded that Fantagraphics was able to reproduce the cartoons as beautifully as they did.

SPURGEON: You mentioned his retirement. How serious was the congressional campaign? When I was doing his obituary for The Comics Journal

, I remember thinking that there was a bit of bluster to how he approached that run at office, like he wanted to convey this confident personality, but I have no idea what he wanted to do.

DePASTINO: Mauldin retired from daily cartooning in April 1948 (a tumultuous period we'll cover in the next volume), and one of the things he did during this 10-year leave from cartooning was run for Congress in 1956. It's tempting during this year of vanity campaigns to think that Mauldin was somehow trying to remain relevant or make a statement by running for Congress as a Democrat in Rockland County, NY. There was certainly some of this, but Mauldin really had only one speed: full throttle. He ran hard against a formidable candidate and wanted very much to win. By this time, he was a

Truman Democrat advocating a strong national defense, support for small farmers and businesses, and a Fair Deal for labor. He had a platform and gave somewhat wonky speeches on policy. He was no newcomer to politics and had campaigned hard for

Adlai Stevenson in 1952 and had served as head of the

Americans Veterans Committee. He knew what he was doing. But he ran in a very conservative Republican district that hadn't elected a Democrat since 1936.

His opponent,

Katharine St. George, was

Franklin Roosevelt's cousin on his mother's conservative Delano side. She got hold of Mauldin's raw FBI file, which had grown during the late 1940s, and used the information in it to smear him as a Communist sympathizer. Mauldin's campaign never recovered from that, and he lost by a fair margin, though scored better than any Democrat had in 20 years. He learned a lot during that campaign about politics and himself. One big lesson, he said, was learning that politicians lie to get elected. He himself had told small farmers that he would help them if he were elected, even though he knew there was really nothing a Congressman could do to ease their plight. "I don't trust any of them," he said of politicians afterwards, "but I can't bring myself to hate them either."

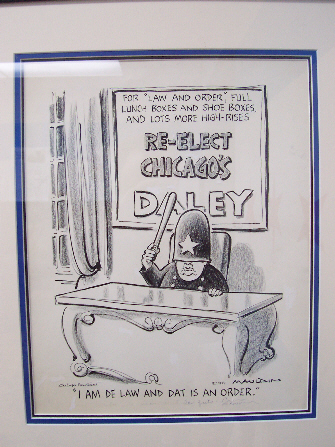

SPURGEON: How happy was he at the Sun-Times? I've talked to a couple of people that worked with him, and what they remember mostly is that he was very devoted and very much a drinker. Was there something about 1960s Chicago and its Daley Family hegemony that was conducive to what he wanted to do in the way post-War America wasn't, or had he changed by then?

SPURGEON: How happy was he at the Sun-Times? I've talked to a couple of people that worked with him, and what they remember mostly is that he was very devoted and very much a drinker. Was there something about 1960s Chicago and its Daley Family hegemony that was conducive to what he wanted to do in the way post-War America wasn't, or had he changed by then?

DePASTINO: Mauldin changed mightily several times in his career. When he arrived at the

Chicago Sun-Times in 1962, he was still a Cold War liberal in the vain of his 1956 campaign. His cartoons were very smart, incisive, and witty, but they didn't have the counter-cultural punch that his earlier and later work would have.

Marshall Field gave Mauldin great latitude at the

Sun-Times. He wasn't edited or given boundaries like he had been at the

St. Louis Post-Dispatch, and he warmed to his newfound freedom. He did his best work, as his son recently told me, when he was surrounded by smart, interesting people. He wasn't an intellectual. He couldn't create elaborate and fascinating work in solitude (something he had tried to do during his 10-year hiatus from cartooning). he needed to be out in the mix, on the streets, up front, participating in events and receiving stimuli from outside in order to create. He worked best on a regular schedule, every day at the drawing board and out covering stories, keeping himself at the top of his game. He had to be completely devoted or the well went dry. He was a very high-functioning alcoholic so long as he was surrounded by stimulating people and events.

Mauldin changed utterly in 1968 after the

Democratic National Convention in Chicago. I don't know if he took on Daley a whole lot before 1968 -- I'll have to go back and check -- but Daley became one of his favorite targets afterward. Mauldin dropped his Cold War liberal attitudes and embraced the counter-culture. He grew long hair and a beard, the whole bit. It really seemed to free him up to be more outspoken in his work. Few men his age found such freedoms in the counter-culture as Mauldin.

SPURGEON: I know that Bill Mauldin's meaning to veterans has been pretty well established. What do you think he has to say to cartoonists? As a writer yourself, what do you take away from his professional example?

DePASTINO: Mauldin talked a lot about what went into a perfect cartoon. A perfect cartoon doesn't need words. It doesn't need stock symbols. It hits you where you live -- in the gut -- sparks a reaction and leaves a mark. Like so many 20th century artists, Mauldin adhered to architect

Mies van der Rohe's "less is more" ideal. Make your point, achieve your effect as simply as possible. This isn't just a parlor trick to see how crafty you can be. It's also a way of compelling your audience to do some work, to fill in the space with their imagination and judgment, and to focus on the simple truths. It's a way of engaging your audience with the moment. Think of Mauldin's

cavalry sergeant shooting the jeep, or

his grieving Lincoln Memorial, drawn on November 22, 1963, or

Willie and Joe in an apocalyptic landscape out of which grows a single flower on a shattered tree limb. Willie beholds the flower and says, "Spring is here!" What an expression of hope, a recognition of beauty amidst the carnage. So simple, yet so profound and eternal. It makes one realize the beauty and depth of experience that is all around us, if only we would take the time to notice it, to breath it in. The most important truths are simple ones. Mauldin's best cartoons, and our own best work, whatever the field, reminds us of that.

*****

*

Todd DePastino

*

A Life Up Front

*

Willie & Joe: The WWII Years

*

Willie & Joe: Back Home

*****

* cover to the new collection of Bill Mauldin's post-WWII cartoons

* cover to DePastino's biography of Mauldin

* three of the astonishingly sour but brilliant cartoons in the new collection

* a photo by me of a Mauldin original mocking Mayor Daley

* a kick-ass cartoon from the post-War period; my goodness (below)

*****

*****

*****