Home > CR Interviews

Home > CR Interviews CR Holiday Interview #15—Rina Piccolo

posted March 22, 2012

CR Holiday Interview #15—Rina Piccolo

posted March 22, 2012

Rina Piccolo

Rina Piccolo is one of the more prolific cartoonists working. She has a daily syndicated strip,

Tina's Groove, has anchored the Wednesday slot of the

Six Chix feature for more than a decade, makes a multiple-installments-per-week webcomic

Velia, Dear and produces any number of

gag panels for a series of clients. Any one of those could conceivably take up a cartoonist's entire drawing-table workweek. Piccolo's comics are consistently well-crafted. It's a consistent delight how fundamentally good-looking

Velia, Dear remains episode to episode, for example, given Piccolo's overall workload. I was happy this daughter of Toronto (currently living in New York City) was able to make time for an interview despite all that she has on her plate, and greatly enjoyed our conversation. – Tom Spurgeon

*****

TOM SPURGEON: I was wondering how you arrange your work week. Given how prolific you are, I assume you're one of those disciplined, regimented cartoonists that everyone else hates.

RINA PICCOLO: That everyone else

hates? [laughs] Why do they hate us?

SPURGEON: You're too organized; you're too on the ball, Rina.

PICCOLO: Well, you know what? Here's the thing. This is what I believe. If you want to put out a lot of work, it has to in some way be organized. There's gotta be some kind of rhythm to it. Because without it, nothing gets done. The way I look at it, my schedule is like a guide. I don't have to think of what I'm doing next, because I've got a schedule that tells me that. So I just jump right in, without wondering, "Now what do I do?" It saves a lot of time. It kind of gets you -- I hate to use this word -- but it kind of gets you into a groove [Spurgeon laughs] and it really helps. It helps. Especially if you've got a lot on your plate. It's kind of like making a list. Are you a list-maker?

SPURGEON: I am sort of a list-maker, yeah.

PICCOLO: Doesn't it organize your mind a bit?

SPURGEON: I... think so. At the point it's so ingrained I don't know what it does to me. I know I'd be lost without one.

PICCOLO: Right. Exactly. So in some ways it not only makes things tidy in your head, it makes things easier to do.

SPURGEON: So I'm guessing you're a bloc of time cartoonist.

PICCOLO: That means…

SPURGEON: "Monday afternoon, I do this."

PICCOLO: Yes. Absolutely.

SPURGEON: Can you break down a week for me?

PICCOLO:

PICCOLO: I do more of a bi-weekly thing because of my gag cartooning, so sometimes I'll have a little change here and there. But Mondays... Mondays are my hardest day. I try to complete six

Tina's Groove dailies on Monday. Not the writing -- just the penciling and the inking. It takes me all day. It's the kind of day I don't want to do anything else, because that would get me out of it and I wouldn't have that rhythm where I just get it done. Mondays are just the artwork. On Tuesdays, I sit down and write

Tina's Groove for the following week. The reason I do it for the following week is because if there are any problems with the writing I can iron them out. I have time. I don't have to stress over, "Oh no, that one's not going to work." I give myself a whole day to do that, and I usually pump them out -- I get my quota done. Wednesdays I write for

Velia, Dear, and then Thursdays I draw it. I draw three

Velia, Dear strips. It takes me another whole day to do that. And then Friday is an open day. I can either tie up loose ends if I didn't get something done during the week, like the story on

Velia, Dear if there's a problem with it and it needs tightening up, I'll do that. Or anything still to do with

Tina's Groove, I'll do. Friday I use to write gag panels. The drawing of the gag panels I'll do a week later. [laughs] This is where it gets dicey, because I have to use one of my days -- or at least half a day -- to draw up sketches for gag panels. Which I then submit to a number of places.

I forgot Saturday! [laughs] Saturday is basically a shorter day. I do a

Tina's Groove Sunday, pencil and ink. And my one

Six Chix. That's when I get

my Six Chix done. On Saturday. It takes no time at all, so Saturday is an easy day.

SPURGEON: How tight are your scripts? I know you mentioned to Sean Kleefeld in an interview that you work with the dialogue as you're drawing. How tight is the script going into the drawing part of it?

PICCOLO: Oh, it's tight when I'm drawing it. I might make slight changes here and there, but once it's written it's pretty tight.

SPURGEON: And you employ an actual, written script?

PICCOLO: Yeah. I break it down before I draw it; I do a little thumbnail. I know how the panels are going to look. You know all of this stuff.

SPURGEON: I do, but I wondered if you considered that element of it part of the writing or if you considered that part of the drawing.

PICCOLO: That's an interesting question. Oh my God. You do know this stuff. [laughs] Of course you do.

It's both. Sometimes if it's the type of writing that has no words, then it is the breaking down of panels -- what's the action in this panel, what's the action in that panel -- that I consider part of the writing. And if there's a strip that's more action than dialogue, I will write it with pictures. In thumbnails. So that it will hopefully carry the story.

SPURGEON: You've been around for quite some time now. 1989 is what sources like Wikipedia suggest was your starting date. The thing is, you were pretty deeply involved fairly quickly -- you weren't just scrambling for a placement here and there; you did books and collections of your work in the '90s.

PICCOLO: Oh, my God. That was like another life. [laughs]

SPURGEON: Do you remember the initial impulse, the moment you decided, "I can do this professionally."

PICCOLO: Yeah, and it was around 1989. I mark that date as my first published cartoon. I'm pretty amazed by that. I had no idea how publishing worked. I was completely ignorant. I didn't know that there were people out there that did illustrations and cartoons and they submit things, and then magazines and books publish them. I had no idea of the mechanics of how things worked. I read an ad in Toronto's weekly magazine which is kind of like

The Village Voice:

Now Magazine -- it still exists in Toronto. They had a comics guest spot. They were going to do one cartoonist a week. I had these drawings, I had these cartoons and I had some comics. And I thought, "Why don't I just send them in and see what happens?" And I was urged by friends as well. I would show these things to my friends. They'd say, "This is hilarious; this is really great." If they liked them, maybe others would like them.

So I sent them in. And let me tell you I was pretty shocked to get a response back. And they not only published the first one, they published five of them. So I was in for five consecutive weeks. And then they dropped the feature. [laughter] At that point, I kind of started to think, "Hey, I've had luck here... what's to stop me from having luck somewhere else?" This is always my advice to young cartoonists who ask, "How do you know if you've got it, if you've got work that saleable?" I always tell them don't ask your friends and family. They love you, so they're not going to give you the right answer. Get the opinions of strangers, complete strangers. Editors of magazines. Preferably in a professional situation, so you can get a

good answer. And that's going to be the true answer.

SPURGEON: One of the things I'm tracking with some of the younger cartoonists out there is that we live in a very social media-oriented world, and it seems like more and more people are finding feedback

SPURGEON: One of the things I'm tracking with some of the younger cartoonists out there is that we live in a very social media-oriented world, and it seems like more and more people are finding feedback just

from a circle of friends. If you get 40 of your friends to comment on something you did, you think, "That's great." And if you get 80, you think, "Wow, I'm killing it." What was in your character do you think that you wanted to publish? Because showing work to your friends can be a very satisfying thing. What was it about getting it out there professionally that appealed to you?

PICCOLO: That's a good question. I have no idea. I often ask that myself to this day. Apart from the fact that there's money involved, and that gives you a little bit of "Wow, I drew a picture and someone gave me money for drawing a picture." I come from a family of workers. I mean real workers. My dad was an Italian immigrant who worked in construction for half of his life. For me growing up, work itself was torture. It was

hard. To think that I could sit down and draw a picture and then someone sends me a check for it? Forget it: that's like a dream!

Like I said before, I didn't even think that happened. [laughs] I didn't know who these people were that were drawing comics for the comics page. So I guess it was a thrill. It was a real thrill for me and I think for anybody to see their name in a publication and see their work in a magazine viewed by a million people or whatever -- I don't know what their circulation was -- and getting a reward, a

financial reward for it...? At the time, that was enough for me, and that's when it became an idea in my head that I could possibly make a career out of it. I could spend my days, spend my life doing this. It was like, "I have to start doing it earnestly now." And it just snowballed. [pause] Very slowly. A very slow snowball moving very, very slowly. [laughs]

SPURGEON: What kind of support were you getting from your family as your career developed?

PICCOLO: My parents were very supportive of anything I wanted to do. They did question it. "Is this going to be your job?" "Are you going to make enough money?" I think it was because they thought... you know, this is something I've been inwardly analyzing. If my brothers did this, I think if my brothers had done this, my parents wouldn't have been as supportive. Because they're men, right? They have to grow up and get real jobs. I was the girl. In a weird sense that was an advantage. It was like, "Oh, she's going to grow up and get married and settle down. And her husband will take care of her." That's how they look at life, or at least looked at it back then.

So they were supportive of me because they thought, "Let her do this and see where it goes. It doesn't matter because she's a girl anyway." [laughs] It's

kind of like an advantage. I think that has a lot to do with it. I'm talking about the older generation: my parents and my uncle and aunts. There was also a generation down from that, with a little bit more education and a little more Canada-ized, having grown up with the culture. They were a little more understanding of what I was trying to do. What I am trying to do. [laughs] I'm still trying to do it!

Some of my biggest fans are right there, my family. That's nice to know.

SPURGEON: The offer to be part of the group of cartoonists doing Six Chix

... When that came in back in 2000 or so, was there any hesitation to take on that gig? That's a unique offer in that you're not getting your own strip, you're working with other people; there's also a very strong identity placed on it because of the premise. Was it easy to accept that gig?

PICCOLO: Yeah, I have to say it was easy. It was exciting for me because it meant syndication. At the time, when [then King Features editor]

Jay Kennedy offered me a contract for

Six Chix, we were still working together on

Tina's Groove -- even though it wasn't called that yet. It was just a strip. He came to me and said, "There's something else I've got for you, but it's only one cartoon a week, so we can still do a strip."

At the time I didn't feel, "Oh, well, that's too much work for me." I felt like I could do one gag panel and still do the strip if it were to happen. So yeah, it was something I did not hesitate on at all. Because it was the kind of the thing I knew I could do. I started out doing panels. It was the strip thing that gave me a lot of anxiety. I wasn't yet a comic strip artist at that time. I was a gag panelist.

SPURGEON: So what was the impetus to move from gag panels into strips, then? Was this something you were personally motivated to do? Did Jay convince you it was a good idea?

SPURGEON: So what was the impetus to move from gag panels into strips, then? Was this something you were personally motivated to do? Did Jay convince you it was a good idea?

PICCOLO: I think Jay had a lot to do with it. One of the things he used to talk to me about was sale-ability and marketability. It's not that they just want a great comic strip, they want to be able to sell it. The thing he kept harping on me about was that gag panels don't really work on the page. They're very hard to sell. There are fewer spaces for gag panels than there are for strips. So your best bet if you wanted to be syndicated was to do a comic strip. I thought about it, and he asked me to come up with a few premises to work on... the whole thing took years. The first year I would say I was learning how to deal with characters and situations. So yeah, he had a lot to do with that. I went with it, and I learned how to do a comic strip through him.

SPURGEON: I was edited by Jay Kennedy for a time period, too, and my memory was that I was fairly resistant to some of his advice, not exactly to my credit. Was that a good relationship for you?

PICCOLO: I know what you mean by that, because Jay was very hands-on. I know from talking to other cartoonists at other syndicates that their editors basically said, "Okay, there you go. Bye. Do your strip." [laughter] And I was like, "Really? It's like that?" Because Jay would literally hold my hand.

I have to tell you, though. I needed it. I wasn't confident enough. He really did help me. In the very beginning, the first year or two years of syndication, I

did want him to call me and tell me if something was off, or if something didn't make sense. That's what I needed, I really needed that coaching. After about three years, I literally went into his office with this big speech prepared on how I think I could do it on my own now and he doesn't have to call me every week and I don't want to have to send in sketches before inking things. I wanted to be independent of his day-to-day, hands-on editorship.

So I walked into his office and he said, "Before you begin" -- he knew I wanted to talk -- "I think you're okay to go on your own now. I won't call you every week." [laughter] I was so happy because I was confident. This was three years in, three years of syndication. I knew I could do this. He would still read them.

Tina's Groove was still a relatively new strip, so he would read the proofs before they went out. If there was anything out of line, he would call. But by then I knew the rules. [laughs] "The rules."

SPURGEON: What was the hardest thing for you to learn? Where was your learning curve the most dramatic?

PICCOLO: The characters. Yeah. That was the toughest thing. I guess I grew up -- at least as a cartoonist doing comics. Doing four-panel comics and gag cartoons, there's very little character involvement there. My comics were very plot-driven at first, or just straight humor. Here I was with this cast of characters, and I didn't know you could just put them in situations and the gag would come that way. I would work backwards. I would come up with a gag and then have my characters deliver it. Which sometimes I still do, because it makes for a good gag, I think.

SPURGEON: In your gag work, do you have recurring characters like some cartoonists do? I looked at a bunch of the Six Chix Wednesdays, and that's essentially a gag strip shaped to fit where a daily goes. It looked like there were a few character types that recur.

SPURGEON: In your gag work, do you have recurring characters like some cartoonists do? I looked at a bunch of the Six Chix Wednesdays, and that's essentially a gag strip shaped to fit where a daily goes. It looked like there were a few character types that recur.

PICCOLO: Yeah, they do recur. The old lady is in there -- I do a lot of little old ladies. I'm probably just influenced over the years by other gag cartoonists. There's the everywoman and everyman character; I use them a lot. They do recur.

SPURGEON: Now, the lead in Tina's Groove

is a traditional everywoman, at least in that the other characters are a bit wackier and bounce off of her.

PICCOLO: True.

SPURGEON: Is that a comfortable way to write -- to have this character reacting to the others rather than having to drive the action?

PICCOLO: I think it works. I think she had more guts at the beginning. Jay's input on Tina, the character Tina, and he really believed this and he was right: your main character should be thoughtful and lovable and good. Wholesome good. All the other characters are allowed to have the stuff that in real life most people have -- you know what I'm saying. Most people are Tina's best friend rather than Tina. Tina is so good. She'd never do anything evil to anyone. You know what I'm saying?

I think the humor in

Tina's Groove is that she's a bit of a fish out of water. She's the straight man. She's the only sane person in a world of crazy people, freaks. So that's basically how I started writing it. I was like, "Oh! I get it! It's like

Green Acres. He's the only sane guy and everybody else is crazy." So I started writing it like that. And that started very early on. You can see it in how she looks at everything: "Oh, okay..."

SPURGEON: I wonder if it's difficult to not lose your lead in a strip like that, seeing as how the other characters are a bit looser and maybe more obviously funny. Do you have to, for example, do a Tina day every so often so that the other characters don't run away with the strip?

SPURGEON: I wonder if it's difficult to not lose your lead in a strip like that, seeing as how the other characters are a bit looser and maybe more obviously funny. Do you have to, for example, do a Tina day every so often so that the other characters don't run away with the strip?

PICCOLO: I've thought of that. Because there is a character that sometimes tries to run away with the strip:

the crazy Monica character -- she's the weirdo of the group. I have to be careful it's not all about her. I bring it back. I do find a voice for Tina. Her voice is more... if the joke is coming from Tina, it's going to be a smart, observational type of joke. An insightful kind of thing. If it's a quirky thing, I'll give it to another one of the characters depending on what the joke is.

SPURGEON: One thing I thought reading a bunch of strips going back into 2010 was how strong the other characters are -- and how unpleasant one character was. A wholly unpleasant character is not something I think of with a daily strip. This character was bad enough that if he were on a network television show they might ask you to scale him back a little bit. The character I'm thinking of is called Noel...?

SPURGEON: One thing I thought reading a bunch of strips going back into 2010 was how strong the other characters are -- and how unpleasant one character was. A wholly unpleasant character is not something I think of with a daily strip. This character was bad enough that if he were on a network television show they might ask you to scale him back a little bit. The character I'm thinking of is called Noel...?

PICCOLO: Oh,

that. Oh God.

SPURGEON: You just want to throw a rock at his head half the time.

PICCOLO: I know. I know. I really dug that one deep. [Spurgeon laughs] I wanted to do a long story. Some people liked it. Other people were like, "Get rid of this character. Because I

hate him."

SPURGEON: [laughs] So how intentional was it on your part to push at those elements of daily strip making, to kind of stir up those reactions?

PICCOLO: It was and it wasn't. I wanted to see where it would go. It went on too long, and I mean that. I thought, "I need to do this long storyline." People were like, "Get rid of him! We want Tina back to how she was." And I'm like, "Oh, okay." [laughs] "Well, that's a good sign at least."

SPURGEON: It's all a loyalty test, you're saying.

PICCOLO: I also did it so I could push her character. How secure is Tina? She

is human. She's a girl. She has feelings. So let's make her fall in love with a jerk and see what happens. That's what happened. She fell in love with an idiot. And readers wanted him out of the picture.

SPURGEON:

SPURGEON: Tina's Groove

is a workplace strip -- much of the action focuses around a specific work setting. Part of the idea with a strip like that is that people who share that experience with the characters are better able to identify with the strip, and you find champions in that segment of the populace. Has that concept as seen in Tina's Groove

been a strength of the feature, do you think? Have you liked that aspect of it?

PICCOLO: Yeah, I think so. I get a lot of mail from restaurant people. When I go to Toronto, a lot of family members work in restaurants and the service industry and they always tell me, "Oh my God, I saw another one of your cartoons on a kitchen wall." Or a bathroom wall. Or on a cash register somewhere. I do get mail from people in the service industry: "I can tell you've worked in restaurants before."

Have you ever worked in a restaurant?

SPURGEON: Nothing past the kitchen at a summer camp.

PICCOLO: It really does get as freakish as what you see in the strip. So that's a strength, I really think it is.

SPURGEON: Did you get a sales bump when Cathy

decided to go? It was thought your strip might be one of the beneficiaries of the open slots that came with Cathy Guisewite's retirement.

PICCOLO: A little bit but not a lot. I don't think anyone did. I think it was overestimated the number of papers that she was in. It wasn't as many as everyone thought. And papers just dropped

Cathy and then didn't pick up any other strips. Which was bad, because it was their way of going, "Okay, another one we don't have to pay for." I

think that's what happened. That might be wrong. This is what other cartoonists were saying at the time. This was buzzing.

SPURGEON: Cathy Guisewite and Cathy

had this sales hook of "This is a strip about a female character from a female cartoonist. You want one of these in your paper for your female readers." Do people still think in those terms? Do people see your strip that way -- is that a way in which it appeals to newspapers?

PICCOLO: I think syndicate people still see it that way, and to some extent newspaper editors as well. "We don't have

this kind of strip; we don't have

that kind." Even if you look at the sales kit, it's all, "Yeah, this is a girls' strip." I hate that term, but that's the mentality out there. "We already have

Cathy; that's our girl strip." There isn't just one female voice. There are

many female voices. You can have two girls strips. [laughs]

I don't think most readers look at it that way. To them it's just a comic strip about a waitress.

SPURGEON: She is

a waitress. Some commentators on pop culture have written recently about an interest from consumers of entertainment in downturn culture. Tina's a working person, not a successful businessperson or anything high-powered. Have you received any interest in the feature based on that? Like if she were a well-connected lawyer, she wouldn't be as interesting as she is with this very real job. Have you seen any interest in the feature based on that?

PICCOLO: No, I haven't. That's interesting, though, because Jay used to say that. This was years ago. He'd say there were too many prominent lawyer-type characters on television; there was almost nothing on the regular girl next door. What does she do? She works at Wal-Mart, she works at this restaurant. He used to talk about that a lot.

SPURGEON: So he was prescient.

PICCOLO: Yeah. Strange. [laughter] I do see it on television over the last few years, but I haven't had any interest in the strip that way.

SPURGEON: Your webcomic,

SPURGEON: Your webcomic, /Velia, Dear

-- it's almost like you had too many reasons to do it to not go ahead and do it. You wanted to do another strip, you had more ideas than you could use, you wanted something set in Toronto, you wanted something a little freer than the restrictions you have in mass syndication, you had some process things you thought you might enjoy in doing it. The question I have is that even though you wanted to free yourself up with a new project, Velia, Dear is a very traditional strip. What made you want to do another traditional strip?

PICCOLO: You think it's a traditional strip?

SPURGEON: In terms of the form.

PICCOLO: I must have a one-track mind. It's interesting that you ask that question because it will lead me to tell you something else. But you're right. Yeah, it is traditional. It's a three- or four-panel strip that ends in something -- a gag or whatever. And you know what? I'm telling you, I had a one-track mind. I'd been working on

Tina's Groove for so long, that when I sat down to work on a webcomic, it was like that was the only comic I could think of doing. The same arrangement of three or four panels. The only thing that differed is that I took it in another direction. I started writing longer stories. It wasn't gag a day. If you look at it today, there's no way you could understand it without knowing what is going on. It became a continuity strip.

SPURGEON: What's the other thing you wanted to tell me?

PICCOLO: I'm planning -- I haven't said anything yet -- I'm planning to break away from that traditional comic strip format. What I'm saying is that it's going to stop being a traditional webcomic and I'm going to try and do more comic-book like stories. What would you call that format? I'd just be doing a two-page story, or a three-page story or a one-page story. And I'd be using the same character.

SPURGEON: I think that's just called a comic. [laughter]

PICCOLO: I'm too close to it now! It's a comic, all right? [laughs]

To tell you the truth, Tom, it's like this. It's a treadmill doing the daily strip and then the three webcomics:

Velia, Dear has run almost two years now. In the next two or three months it will be two years. I did say it would be a two-year experiment. I want to produce stuff that is not deadline driven. And so

Velia, Dear will become... it's not going away. I think people presume that they're always going to get the thrice-weekly dose of the strip, and that's going to stop. But the site will still be up, and I'll offer the readers more comics -- it might be every couple of months or so -- so that I can do a collection.

I really love these characters. I don't want to end the webcomic and say goodbye to them forever. The reason why I'm ending it isn't that I don't like it. I really like it. It's just the time, the time involved.

SPURGEON: Doing the longer storylines in

SPURGEON: Doing the longer storylines in Velia, Dear

seems like it was a big deal for you. Did you have fun figuring out you liked doing the longer storylines?

PICCOLO: Yeah, absolutely. Also figuring out

how to do them. I'm figuring out how to write... well, fiction. And it came at the same time I started writing a lot of prose. Going to the new format for

Velia, Dear will give me more time to write and work on the

Velia, Dear project. It should free up a couple of days a week. That will be enough time to delve into this fiction stuff.

SPURGEON: Are you happy with Velia, Dear

as a creative project? Has it been rewarding?

PICCOLO: I'm very happy. I'm very happy with it. Yesterday I was writing -- not really writing, what was I doing...? I was writing

Tina's Groove but thinking about

Velia, Dear and thinking about how I was going to end the current story. I didn't know how it was going to end. It just came to me. While I'm not going to tell you the ending, it gave me a lot of joy to know it could end like that. I can end the webcomic like that. It totally turns it around.

I'm not making any sense, because I'm not telling you what it is. [laughs] It was exciting to me yesterday.

SPURGEON: We need more mysteries, Rina.

PICCOLO: I tend to get a little crazy with these stories, but that's the fun in it.

SPURGEON: How Toronto is that strip? You did PR early on about drawing specific places and making references you can't make in a syndicated strip. Do you have Toronto readers?

PICCOLO: I do have Toronto readers. I had this one strip -- it ran this last Monday. It had a lot to do with an inside joke about the Toronto Transit System, the public transportation in Toronto. Everyone likes to make fun of the transit system in their city, and I got some response where people not even from Toronto knew that being from there I'd make fun of that system.

It is a Toronto strip, and I want to give it a sense of place. The way the houses look... that's my city. I've had subway scenes where I show what station it is. Every time I need to refer to a street name or an intersection, it'll be a real intersection. With

Tina's Groove, it's kind of like a no-place place. I say "Main Street" a lot. But in

Velia, Dear the characters are definitely Torontonians making references to things that are solely in and of Toronto. I wanted that. I love that city. [laughs]

SPURGEON: Comics used to chase after a more specific sense of place a bit more frequently than they do now.

PICCOLO: That's one of those things I think you learn after you do this stuff for a while. Even if your place is fictional -- like in

Tina's Groove, where they're just in a town -- it's still important to have a sense of place for the characters. It's one of those things that readers subconsciously pick up.

SPURGEON: The wash technique you use in

SPURGEON: The wash technique you use in Velia, Dear

is very attractive.

PICCOLO: Thank you.

SPURGEON: I wish I had a really cool question about that approach, but I don't. I mean, is that just something you enjoy? Is it something you wanted to do because you can't do that on the newspaper page? Because I'm pretty sure you couldn't send a wash strip down to Reed Brennan.

PICCOLO: For newspaper stuff? No. You couldn't. Otherwise, Patrick McDonnell would be all over that. If they suddenly said you could do that, he'd be all over it. He'd be the best, too.

SPURGEON: So doing wash in Velia, Dear

was a way of just getting to work with that technique?

PICCOLO: Oh, yeah. Absolutely. I've always loved the wash. I love the half-tones. The first year of

Tina's Groove I used Zip-a-tone and it's not the same.

SPURGEON: The general desire for that artistic effect, that look: that's a holdover from your gag-panel work, right?

PICCOLO: The gag panels later on. Earlier they were just black and white. I didn't even know what wash was. That's how ignorant I was. I'm like, "How did they get that gray part there?" I had no idea. It wasn't like I could jump on google and ask. There was no google. So I spent a lot of time figuring things out for myself.

SPURGEON: What were you seeing that made you think this would be attractive?

PICCOLO: I read

The New Yorker every week, so I'd see those. And the collections, I would buy those. A lot of the old stuff. I would look at collections, like

the Sam Gross collections. I loved them. I was like, "Wow. I want to learn how to do that."

SPURGEON: Will that technique continue into the newer work as well?

PICCOLO: Yeah, absolutely. The basic look will be the same.

SPURGEON: Was it difficult at all in the print collection of Velia, Dear

you released getting the art to print correctly?

PICCOLO: To tell you the truth,

Brendan [Burford, Piccolo's husband] took care of the production on that. I don't know that stuff. [laughter] It looks nice on the page.

SPURGEON: Do you

SPURGEON: Do you like

your lead in Velia, Dear

? Because there are unpleasant aspects to her personality. Do you find working with that character satisfying above and beyond the novelty of working with someone that's not

a daily syndicated strip lead?

PICCOLO: I do like her. She's not perfect. That's the thing about

Velia, Dear; I can get away with a lot more. It's satisfying to me. After a while, when people say "You can't say this" and you have these other stories, you just want to do them. I like the stuff in

Tina's Groove; not everything I do has to have an emotional undercurrent. I like to think the character in

Velia, Dear are less two-dimensional than the ones you see in

Tina's Groove.

SPURGEON: Spirituality and religion is a recurring source of plot and humor in Velia, Dear. Has that been a satisfying place for you to go, a place you personally find amusing?

PICCOLO: I tend to naturally go there. You mentioned my earlier collections... one of them was

Kicking The Habit, which was cartoons about the Catholic Church. I was raised Catholic, and I'll probably never get over it. [laughter]

SPURGEON: You're not mean-spirited, though. The characters in Velia, Dear

may evince a point of view, but they're not savagely critical of the choices other characters make.

PICCOLO: Even if you read those gag panels, they're not mean. It's silly. It's silliness.

SPURGEON: Speaking of which, you spend a good chunk of your work week on the gag cartoons. How much material are you placing with clients?

SPURGEON: Speaking of which, you spend a good chunk of your work week on the gag cartoons. How much material are you placing with clients?

PICCOLO: It's been pretty good. Not including

Six Chix I have three clients. I assume you mean the magazine stuff.

Parade is ongoing. I just got into

Barron's, and then there's

Reader's Digest. There's another thing I can't talk about yet, because I'm very superstitious, but there's another outlet for my gag cartoons that's not exactly a publication.

It's pretty worth it for me to keep doing them, and they're a lot of fun.

SPURGEON: As opposed to the joys of telling a story, is a gag strip more of a problem-solving creative process? When a gag strip works for you, what do you like about it?

PICCOLO: I like that it makes me laugh. If when it pops into my head it makes me smile or laugh, there's something in it to hold onto. That does happen, although usually that phase only lasts a couple of minutes. When you're working with something and it's a shock to you, a surprise to you, and it makes you laugh -- you instantly want to show it someone else. When it works, it's a lot of fun. When it doesn't, it's not fun at all.

SPURGEON: One thing when I look at your panels is that they're very accomplished in terms of the basic craft elements -- you're not going to get in your own way, not going to be unable to do something on the page. How long did it take you to get that comfortable with that element of your work?

SPURGEON: One thing when I look at your panels is that they're very accomplished in terms of the basic craft elements -- you're not going to get in your own way, not going to be unable to do something on the page. How long did it take you to get that comfortable with that element of your work?

PICCOLO: I think years. [laughs] I remember doing cartoons for fashion magazines:

Glamour,

Mademoiselle. That was mid-'90s.

SPURGEON: I am unfamiliar with the tradition of gag cartooning in 1990s fashion magazines.

PICCOLO: I remember

Lynda Barry took my spot. I love her, but.... [Spurgeon laughs] I was like, "That's great. They're going to buy her every month." They later dropped the cartoons. They don't run any now, which is unfortunate.

Even back then I felt I knew what I was doing. I became even more comfortable with it in the last five years; I became extremely comfortable with it.

SPURGEON: What's the difference between your work now and the work you used to do?

PICCOLO: The older work is ugly? [laughter] It's embarrassing? [laughter]

King Features took over the

Tina's Groove web site, and when I saw they had the archives back to 2003, I cringed. That stuff is up there where people can see it...!? I'm so embarrassed. But then I think of other cartoons and how those characters went through transitions as well. I imagine every cartoonist is embarrassed by the look of their earlier stuff. I can safely say that, because talking to my friends they say that as well.

SPURGEON: You're locked into a cycle with the strip where you're at the slow grind stage in terms of sales -- it's unlikely you'll ever go through another period where you pick up a bunch of clients at once like a strip might when it first comes out. Is that frustrating at all, that you can only pick up strips a few at a time? Does that cause anxiety for you?

PICCOLO: It did cause a little anxiety. With print vs. digital becoming an issue, I was worried about what was going to happen there. Around 2008, those were the worst years: the recession hit, and the strips suffered for that, too.

I think it's turning around. Something I had not thought possible two years ago is happening. There are web sites out there that are news web sites that are buying comic strips from syndicate at the same rate as newspapers. So when I heard that, and I'm in one of them -- they want to curate their comics section the way an old-fashioned newspaper curated their page. This is on the Internet. When you hear of that happening, things are turning around. They're turning around.

SPURGEON: But is there any reaction when you go through a really strong period, you feel you have a great year and the strip is hitting on all cylinders, and the end result is you pick up four papers?

PICCOLO: Oh, absolutely. But you can't even think of it in those terms. If you do, it just cripples you. I used to be very anxious at the very beginning, because I heard the stories of strips launching and crashing six months or a year later. Once I passed two years, people were saying, "You're in enough papers, and it's two years. You're okay." So I started feeling a little better.

I can't think about stuff like you just said. [laughter] Thank you for putting that in my head, Tom.

SPURGEON: I'm here for you.

PICCOLO: Anxiety is not good for creativity. I've learned that. It's not good at all.

*****

*

Rina Piccolo

*

Tina's Groove

*

Six Chix

*

Velia, Dear

*****

* the cartoonist as photographed at TCAF 2011

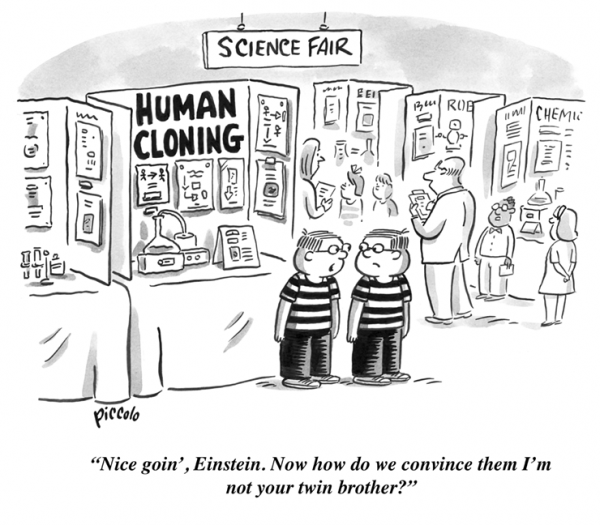

* a

Six Chix gag

* one of Piccolo's magazine gag cartoons

* two from Piccolo's Wednesday slot at

Six Chix

* the wacky Monica character

* Noel at his Noel-iest

* the workplace setting of

Tina's Groove

* three from

Velia, Dear

* two from the gag cartoon archives

* one more gag cartoon I like (below)

*****

*****

*****