Home > CR Interviews

Home > CR Interviews CR Sunday Interview: Bob Fingerman

posted April 7, 2013

CR Sunday Interview: Bob Fingerman

posted April 7, 2013

*****

I have a lot of fond memories of Bob Fingerman from the mid-1990s when the publication of his

Minimum Wage series coincided in rough fashion with my run as an editor at another Fantagraphics effort,

The Comics Journal. I liked that his comics engaged with sex, and that they found other ways to depict attractive people that didn't depend on 1950s gag cartoon standards and that the New York he described in his books seemed to match up with the city as I experienced it on twice-yearly visits. I enjoyed Bob's company at comics shows like San Diego, and we've stayed friendly since. I was really happy to see that

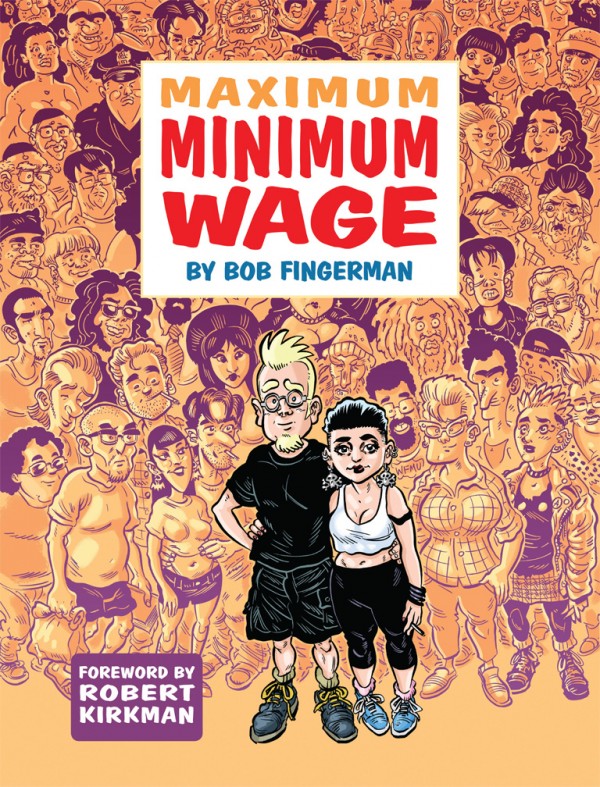

Image Comics had published an immense hardcover of the

Minimum Wage comics and all the extras as

Maximum Minimum Wage. I think that it's work that deserves to be seen by a different generation of comics-readers, and as we talk about below, the fact that there's a market on television for shows about people in New York leaving lives of mostly comedy but significant tragedy blended in changes the potential context in which the work might be received. I'm grateful to Bob for his time. As is made clear in the initial exchange, we both kind of noodled on this a bit. -- Tom Spurgeon

*****

TOM SPURGEON: You've been interviewed a lot for this book, and the story of how this project came together is out there in general terms. I wonder, though, if readers of this site know what happened that we suddenly have this giant Minimum Wage

collection. Can you talk about how we got here?

BOB FINGERMAN: I don't want to get anyone in trouble... so I might need to see the transcript before it sees print, just for this question.

SPURGEON: I can work with you on that.

FINGERMAN: I don't have the unhealthiest ego. But I don't have a very, I think, big ego, either. So for me,

Minimum Wage was kind of done. It was in the past. I wasn't thinking of doing a big, deluxe, shiny new version of it. [laughs] I was pitching a couple of projects to a publisher. I had a new series I was pitching, and it wasn't what they were looking for. The editor I was pitching to said, "You know what my favorite thing of yours is?" And I knew he was going to say. "

Minimum Wage" And it was. So he suggested something like that would be an easier sell. The projects didn’t come to pass there, but it planted a seed to do a new edition.

I shot an e-mail to

Robert Kirkman. Kirkman was a very enthusiastic fan of

Minimum Wage. He used to send me fan mail back when he was still working in a light fixture warehouse, and he was just getting started, and he started to self-publish

Battle Pope. He would send me issues of

Battle Pope. He sent me these really nice fan letters, which I wish I could find so I could have included them in the book or put ’em up on the web site. I don't know why I can't find them, I can find all my other fan mail. But anyway, he'd always been a vociferous supporter... I'd seen him at comics conventions when people asked him, "What do you consider influences?" and he often mentioned

Minimum Wage. And he and I are friendly. So I sent him an e-mail pitching him everything that had been put into my head and a little bit more. "I want to make this a big 9X12 hardcover. I want to include all of the comics. I want to include all of the covers. I want to include all of the pin-ups..." I really laid it on. About three hours later I got an e-mail back from Robert saying, "As a fan, I want this book to happen. So I'm going to make it happen."

It went from being a bad day to a very good day within a couple of hours, which isn't usually the way things pan out. [laughs]

So it's very nice. It's good to have a longtime fan and friend that's now one of the biggest names in the business.

SPURGEON: Robert is an interesting guy... you know, a chunk of his work right now seems oriented towards television. Is that a concern of yours, and of this partnership on this book? Was there a thought about re-presenting this work for that kind of market?

FINGERMAN: That's I want. I've already been talking about this with... my

management, which sounds obnoxious or show-offy. I wanted this thing to be a TV series back when I was doing it in the '90s. I won't say it got close, but it was in the process. There was a very talented comedy writer I'm friendly with who almost was attached as show runner. When he became unavailable, that's when it collapsed. The thing is, the television landscape was very different in 1998. That's like a million years ago. Basic cable had not blossomed into the fertile, adventurous area it is now. There was nothing like

Mad Men or

Walking Dead or

Justified. There are so many great shows being done on basic cable, let alone premium cable. Forget about the Internet: there was no such thing as streaming shows; no

Netflix or

Hulu. None of that. There weren't shows with the vibe of

Minimum Wage. In a weird way I've always felt -- and this is going to sound egotistical -- that I was ahead of the curve. I'd gotten there too soon. It didn't really find its audience and then years passed and things like it came out and did well.

SPURGEON: What do you think of as works that are of a mind with Minimum Wage

? What are its creative peers?

FINGERMAN: I think things like

Girls and

Louie. Those in particular come to mind. Both are set in New York, both are about struggling people, both balance comedy and drama. The thing about

Minimum Wage is if I wanted one issue to be dramatic, like the abortion one, that was it. I could just go that way. Then I could do a comic-con issue and it would be funny. For me it was what served the story, the tone. On a show like

Louie, he's done some episodes that are harrowing and some that are uproariously funny. His show is a bit more... in a way film-studenty, because he'll indulge himself with strange casting and go off on very surreal tangents. I did less of that. But it's a very grounded show. Except for little indulgences I think it's very grounded. So something like that gives me hope that a

Minimum Wage series could happen now.

I don't know if you ever saw it... there was a British TV series called

Spaced, with

Simon Pegg?

SPURGEON: Oh, sure. Yeah.

FINGERMAN: That's one of my all-time favorite series. I doubt he and

Edgar Wright have even heard of me, but in a weird way that show,

Spaced, which came later than

Minimum Wage, when I was watching that series I remember thinking it was close to the vibe I wanted. That show captured that phase of young people's lives, especially young people that are trying to be creative and find work in a creative field. The fact that Simon Pegg's character is an aspiring comic book artist... it went off in crazy, surreal directions... but it had a sensibility that made me jealous. "Man, the BBC will take some chances." If you can deliver a show on a low budget, they'll say go ahead and try because they're only making a six-episode commitment. I think they're a lot more willing -- at least in those days -- to take a chance. American TV has been prohibitively expensive. I think basic cable has changed that. Look at Louie's deal. Maybe his deal has changed, but I remember reading that so long as he delivered an episode for $250,000, which is nothing in TV terms, they would let him do whatever he wants.

I think the climate has changed. So I would dearly love to see

Minimum Wage as a TV series. And not just because I might actually make some money. [laughter]

SPURGEON: Can you talk about your connection to that kind of story, the story you chose to tell in

SPURGEON: Can you talk about your connection to that kind of story, the story you chose to tell in Minimum Wage

? What is it about that period of life that made you want to create a work about it, that you find affecting when other people do it? Because I can't imagine you would have made all of those comics without some sort of personal connection. This wasn't an extended, laborious TV pitch.

FINGERMAN: Oh, no. I wasn't thinking of TV at all when I first started doing it. In a way it was only when I got ready to stop doing it that I thought in terms of TV.

SPURGEON: What was it about that period in someone's life -- your life -- that you thought was worth exploring? It was a recent period in your life.

FINGERMAN: [laughs] It's not so recent anymore. But it was. I did a panel last week at this Housing Works thing with a couple of other autobiographical comics type people,

Dean Haspiel and

Laura Lee Gulledge.

Ethan Young. I was wrong. I was talking about time giving you perspective on things. Off the top of my head I think I said it had been at least ten years since I had lived what was the basis for

Minimum Wage. It was actually a bit less than that. In a way, I think that what made me want to do

Minimum Wage was that everything I had done before had been pure fiction, pure escapism. I wanted to do something more personal as a challenge to myself. I still couched this in fiction. I've been asked over the years, "Why Rob Hoffman and not Bob Fingerman?" I didn't want to do straight autobiography. I wanted to play a bit fast and loose. I wanted to be able to mix chronologies, use people from different parts of my life. Add some, eliminate others.

I wanted to do something that did feel personal. Where I did feel connected to it.

SPURGEON: Was there something specific to that story? You could have done early childhood. You could have done family memoir. You could have done a genre story set in that same milieu. You consciously chose to tell the story of that relationship and those years. Was it just the romance of that time in your life? Did you think there was a lot of humor to be mined there?

FINGERMAN: I thought it was funny. I thought it would be entertaining. Seldom have I ever sought to do work that would only be interesting to me. [laughs] I always thought it could be entertaining to an audience bigger than any it actually ever found.

I have thought about doing comics about my childhood and adolescence. I wanted to do something... in a way, what I wanted to do, which never fully got realized because I ended the series, I wanted to do the story of a couple that didn't belong together. I thought that would be a different angle. It’s not like I was seeking to do a romance comic. I knew how the story ended. I intended to take it through not its inception, as it's already a thing, but take it through the dissolution of the relationship. At a certain point I didn't want to do that anymore. I've actually thought a lot about coming back to

Minimum Wage, starting it up again.

SPURGEON: Huh.

FINGERMAN: For years I thought about it. But I just thought, "I don't want to go through that all again." [laughs] "I don't want to relive that dark shit." That won't be fun to draw. That won't be fun to write. As an artist, maybe that's a very cowardly thing to say, but it's also a pragmatic thing. If I'm going to have a shitty time doing it, I'm probably going to do bad work. By and large, it is a humor book. So while I was putting together this collection, the solution came to me on how to get back to it. Let's just say I'd pick it up a few years later.

SPURGEON: You mentioned your art... one thing that was striking to me looking at this material again is how striking the character designs were, how you managed to create attractive people that weren't

SPURGEON: You mentioned your art... one thing that was striking to me looking at this material again is how striking the character designs were, how you managed to create attractive people that weren't typically

attractive. There's also this graininess to the setting that's appealing. How hard did you work at the look of Minimum Wage

? Because you were a very young cartoonist when you started doing it, at least a relatively young one in terms of work produced. It looked really different than the work that came before. Did it take you a while to get there?

FINGERMAN: Oh, yeah. I think... I think... I always find it interesting when artists' work doesn't change. There are some artists where you look at their work from 30 years ago and you look at their work now and it looks exactly the same. I don't know if that's a conscious decision, or just a lack of growth. Or they found something they liked and stuck with it.

I can't do that. So my work is constantly changing. It would be very boring for me... maybe it would be better for my career! But I think it would be boring if the art stagnated. I had just come off of doing

White Like She. That's my least favorite book, particularly in terms of the art. I was trying to experiment -- again, do something different. That was my first graphic novel. It was really heavily photo-referenced. I was drawing with rapidographs and everything was just... I was using French curves for making perfect curves. It was really a soul-deadening experience, working on that book.

So for

Minimum Wage, I'm not even sure what it is I wanted to do, but I wanted it to be radically different than anything I'd done before. Right before

White Like She most of my regular work was porno-type stuff for girlie magazines and what have you. I did

Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles for about a year. I started work on

Minimum Wage right before I turned 30. I wasn't a kid, but I was still young. Younger. As a 30th birthday present, I decided to draw something that would be fun in a style that would be fun. I wanted to loosen up. The first

Minimum Wage book looks radically different than what it ended up looking like. I couldn't keep up that kind of looseness. I’ve had a natural tendency to tighten up and make things a little more slick. It's an urge I'm constantly fighting. The art style... it was a very conscious attempt to make it as close to my sketchbooks as I could. So no building up heavier lines with one pen over and over again because I never learned to brush ink. It was draw directly and simply. And of course it morphed as I was working on it, and it became more... I don't know, a Herge clean line. I had to change again. It definitely metamorphosed over the time of doing it, which is why collecting it I went back in and have done some retouching to make the art more consistent.

SPURGEON: I know you did that last time; you did that this time as well?

FINGERMAN: Yeah. [laughs] In my introduction I wrote I was toying with calling this the OCD Edition [laughter]. Michele, my wife, actually forbade me -- I didn't listen -- to do any retouching this time around. I said, "Just a little bit. No more than 10 panels." I think I ended up retouching over 50 pages.

SPURGEON: Oh no.

FINGERMAN: I was completely redrawing some pages. Like I said, it was an obsessive-compulsive thing. I'm going to get it right this time.

SPURGEON: Did you get it right? Are you happy?

FINGERMAN: I like it, but I'm sure if there's another edition... [laughter] Something about this story in particular -- that's why I hope this one will be the last one. If there's more

Minimum Wage I've just got to start with new chapters. I cannot keep fucking with what I've already done.

SPURGEON: Working with that material again, I know I have an answer to this question, but I'm interested to yours: do you see things that are time-machine elements, that are of New York of that specific time? I don't want to cost you a modern television deal if you speak to this, Bob, but I wondered if anything leapt out at you as being specifically New York City in the 1990s.

FINGERMAN: Yes and no. I've already thought about how to pitch this thing as a TV series, and it would be contemporary. There's very little intrinsic to it that you can't just update.

SPURGEON: I agree with you.

FINGERMAN: It's almost all technology. I have people using pay phones instead of cell phones. Nobody's using computers. In a way, the changes are a bit superficial. In other ways, they're not. This was part of the fiction aspect. The part of my life I was writing about, the character Rob... if you did his timeline he's a decade younger than me. As I was drawing it, I made the setting contemporary. He was living this period in the mid-1990s. I was living it in the mid-'80s. So it's malleable. There are some things that he's referencing in the comic that if I really closely examined them, maybe he shouldn't have, where I’d think, "A guy who was 22 years old in 1997 might not make that reference." Particularly before the Internet took over and everyone suddenly became clued in to everything. He would make reference that I would make. I call that an indulgence. Artistic license.

But the time period... ? New York was always essentially... I don't think you could set this anywhere else. Which may be very limiting and just cost me a TV deal. [laughs] I don't know. I'd like to think that New York serves this story better than any other location.

SPURGEON: What about New York serves this story?

FINGERMAN: It's because I intimately know it. Well, here you go. Here's an area where the times have changed so much where maybe New York isn't integral to it anymore. He's a struggling freelance illustrator. Publishing was pretty much all centered here. Certainly if you wanted to do magazine work, this was the place to be. That doesn't matter anymore. The Internet took care of that, for whatever magazines are still using illustrators. That's a diminishing pool. You can be anywhere, though. Anyone can submit. There's a whole chapter called "Art Directors Must Die" where he's trucking around his portfolio? I don't think there's anyone that does that anymore. I might be wrong. There might be a couple of dinosaurs, or retro-hipsters, that actually bring a book around. It's been so long since I pursued that kind of work that I'd have to do some research into how illustrators get gigs now. [laughs] I don't even know anymore.

SPURGEON: One thing that intrigues me about the series, Bob... you talked about being ahead of the curve, in terms of the material you were doing. I wonder if you weren't a man out of time when it came to format as well, Bob. My memory is that Minimum Wage came out right after the boom for the alt-comics -- just after that market got tough, anyway. It even came out in kind of a thin "Graphic Novel" format, initially. And it never seemed settled. Do you remember that as a struggle, just trying to find a way for this material to come out.

FINGERMAN: Oh, absolutely.

SPURGEON: You've had some prose experience now. You've done illustration, too, in addition to comics. How do you look at the vocational struggles you've had in comics. Is there ever a tendency to look at it in terms of some sort of conspiratorial effort against you, the number of times you've had setbacks? Or do you think you're close to finding that one way of presenting your comics that best flatters them?

I mean, I guess since vocation is such a big part of Minimum Wage, I wonder how you looked at your own struggles in that arena.

FINGERMAN: That is a great question. [laughs] I'm not sure I have a great answer for it. This is one of those things, especially if you're answering something publicly, where... I don't ever wish to appear ungrateful. In the plus column, I've had a pretty uncompromised career. I've had greater and lesser degrees of success artistically, but I've pretty much called my own shots and done the kinds of books I wanted to do. But in terms of their timing, their reception or whatever. It's always been a source of frustration for me. Here again, the question of ego. I know that I'm not for everyone, but I'm convinced in a nation of over 300 million people there are tens of thousands that would get what I do. By and large, I think what I do is very accessible. So the whole thing about how you reach an audience, that has always perplexed me. I don't know if it's the timing issue we talked about, or...

SPURGEON: Are you confident that this one will find an audience? [pause] Are you... hopeful?

SPURGEON: Are you confident that this one will find an audience? [pause] Are you... hopeful?

FINGERMAN: I'm hopeful. This is the first thing I've ever released through Image. Image's name brings its own... I think there's a lot of good will between Image and retailers.

SPURGEON: There is right now, for sure.

FINGERMAN: So I'm hoping that that will work in its favor. I also think it's a good-looking book. I'm very proud of it. I think... in way, the design of the book, this is my most overtly eye-catching. In addition to being large I think you'll notice it across the room. I think that might help. [laughs] Over the years I've done some very subtle covers, and I think subtlety may be for the birds.

SPURGEON: This is a terrible question, and I don't want to depress the shit out of you [Fingerman laughs], but Bob, you're my older brother's age. You're a little bit older than I am, not much. The last time I saw you was at a public event, and after we talked I ran into a mutual friend of ours, also around that same age, that was a little freaked because for the first time in a long time he was having a hard time finding a publisher. For whatever reason, he was just wasn't hitting with what publishers want. Is getting older a concern for you?

FINGERMAN: It's a concern. Especially as things keep changing. It's never been easier to get your work out there, and it's never been harder to make a dime from it. This whole phenomenon of giving everything away on the Internet? Say what you will about Harlan Ellison, but he's right when he talks about -- did you see that movie about him,

Dreams With Sharp Teeth? I think it's from that -- you get approached by someone and they try to talk you into doing something for exposure, and basically it's that they're trying to get you to give away your work for free. And his attitude is "go fuck yourself; I've worked really hard at my craft. If you want what I do, pay me." It's Harlan Ellison, and he's a blustery guy, but I appreciate the spirit of that. The last couple of books I've done have been pirated. The second something is made available digitally, boom! It shows up on dozens of torrent sites for free. There are arguments I've had with people where they say, "At least people are reading your work." And I think, "Well, yeah. Maybe. But what's my motivation to keep doing it? I gotta live." It's a very utopian idea, to say, "Art for art's sake" and be happy that people are reading it. But if you're like me, I've always called myself a commercial artist, and if you're not making any money anymore, you're not a commercial artist. You're just an artist. I have no desire to be an artist. I'm not that pure. [laughter] I like the commercial part. It's harder and harder to be commercial.

SPURGEON: I wondered where you thought you fit into this current landscape.

FINGERMAN: That's one of the reasons I wrote novels. I wanted to write them anyway -- this speaks to the restless nature I have, why I don't stick with one title over 20 years. If I really had wanted to bear down, I could be talking about

Minimum Wage #50 now. But I just didn't want to do it. In addition to the artistic cowardice [laughs] I just didn't want to do one thing. I had other things I wanted to do, and I knew one day I'd be dead, and I wanted to try a bunch of different stuff before it was too late. I was hoping the novels would kick ass and open some doors. I'm glad I did them. But mainstream publishing, the whole prose field, is as fucked as any other field right now. Maybe more so. It really is kind of a dinosaur field. It's battening down the hatches against its own doom. I wrote more novels than I got published. Two got published. I have several unsold manuscripts. Both of the books I did publish I wanted to keep going with them. I had sequels. I didn't have sequels in mind when I wrote the, but when you sit down with something and work for two year or so on it, I can see why people do multiple books. You get to know your characters. You like them. I hope most writers are fans of their work. You like what you did and you wonder where the story goes.

I'm proud of the novels I put out and I'm glad they're out there. I would have liked to have gone forward. With things being the way they are, it's not just practical to go forward with them. That's why I'm going forward with stuff for television. The one field I would love be involved in is the videogame field. I don't think I'm too old for it, but I will be soon! [laughter] Videogames is one of the most exciting fields out there. The Roger Ebert and Martin Amises that make these sweeping pronouncements that videogames will never be art, they haven't played one since Space Invaders or something like that. Some videogames are intensely rich, novelistic experiences. Yes, you're running around shooting things or wrecking cars or whatever. But some of the narrative opportunities in games don't exist in any other medium. The idea that you can do branching stories, where you as the player, based on ethical decision you've made, can have a completely different outcome than another player? That's very exciting.

SPURGEON: I think Minimum Wage, the Videogame

would have been my absolute favorite at age 14.

FINGERMAN: [laughs] The opportunities there would certainly be different than in other games. "Go home. Fuck girlfriend. Go to White Castle. Get nauseous." [laughs] "Which do I choose? I'll do both."

*****

*

Maximum Minimum Wage, Bob Fingerman, Image Comics, hardcover, 360 pages, JAN130488 (Diamond), 1607066742 (ISBN10), 9781607066743 (ISBN13), March 2013, $34.99.

*****

* cover to the new volume

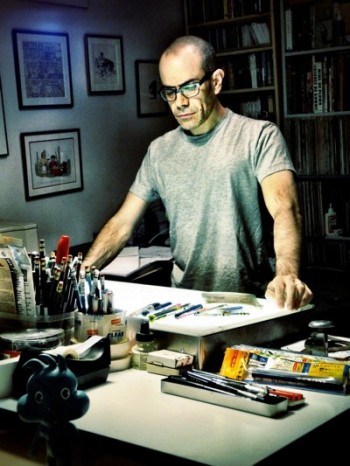

* photo of Bob Fingerman by I think me

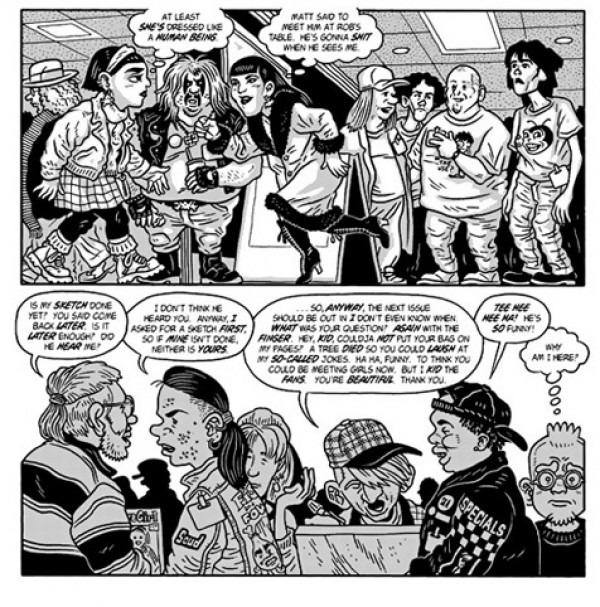

* from the well-received convention issue, now installment, of

Minimum Wage

* the striking character design

* one thing Image did for Bob Fingerman is put him in its creator-driven, "creators at work" promotional series

* an across-the-page panel from

Minimum Wage (below)

*****

*****

*****