January 5, 2014

CR Holiday Interview #15—Kevin “KAL” Kallaugher

CR Holiday Interview #15—Kevin “KAL” Kallaugher

*****

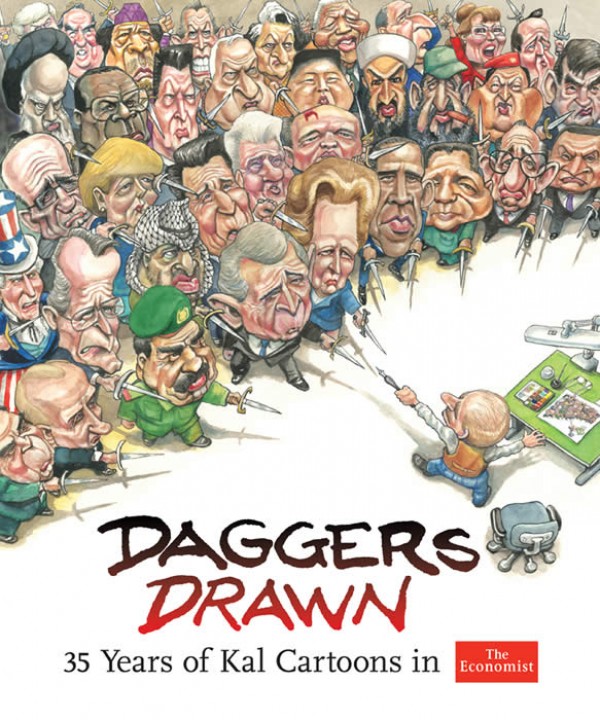

Kevin "

KAL" Kallaugher could be interviewed in full about single aspects of his multi-faceted career. He is a political cartoonist for

The Economist, and his distinguished career for that publication is the subject of the 2013 retrospective

Daggers Drawn, one of the loveliest kickstarted projects put out there by any comics person.

Kallaugher was one of the highest profiles early casualties of the downturn in North American newspaper publishing, and as

a current Baltimore Sun cartoonist may be the only cartoonist of this generation to return in a significant role to the publication that let him go. He is a formidable proponent of animation as a satirical tool (he's an animator that once worked with Richard Williams), one of the most active cartoonists in terms of placing work in shows and taking advantage of institutional arts-opportunities such as residency programs, a former

CRNI and

AAEC president, a

Nast and

Berryman winner, one of the few North American editorial cartoonists with a pedigree of publishing work about Europe, South America and Africa and the only cartoonist I know that toured with

Second City.

I was thrilled to talk to him. You can tell I was nervous by the length of my questions. -- Tom Spurgeon

*****

TOM SPURGEON: 2013 was the 25th anniversary of your initial hire by the Baltimore Sun

. I was always a bit curious about why you made that move then, because it seems like you had a pretty good thing going overseas. What was appealing about that opportunity?

KEVIN KALLAUGHER: Let me try to paint a picture both for you and for me as to where I was in 1988. I'd been working for nearly 11 years in the UK. I had transitioned from being a person that did, largely, caricatures and editorial illustration -- which I did for the first years of illustration career -- to being a political cartoonist. I'd already had at least one job on a daily British newspaper and other jobs on weekly newspapers. I was establishing myself in that way. So in some small way it seems kind of odd that I'd be coming back.

The circumstances were this. I'd come over for one of the AAEC conventions, in Washington DC. The year must have been '86, I believe. There was a cocktail party where Lee Salem, the head of Universal Press Syndicate, and I were having a chat over a drink. He said, "You know, there's a job going in Baltimore." I had never worked in the US. I had immediately upon graduation left the US and gone overseas. The prospect of working the US seemed kind of tantalizing but I hadn't thought it all the way through. Furthermore, I had just about three years prior established my own small syndicate in the US. This was before I was picked up by Cartoonist and Writers Syndicate. I used to send cartoons to the

Philadelphia Inquirer,

Washington Post,

Baltimore Sun, and

Boston Globe from England. I'd do two cartoons a week, which in those days meant I had to do the cartoons, photocopy them and send them airmail to the US. I lost money on the deal because airmail was so expensive. And they would get the cartoons about a week later.

I had been to the

Baltimore Sun. I had a rough idea of what it was like. I packed up a portfolio and sent it off to Baltimore. Then I kind of forgot about for a month or two. In the meantime I signed a new contract with one of my daily papers I was working on, and my wife and I had just bought a new house. Then I got a letter back from the Sun that said they'd love to have me come over for an interview. So I saw the interview as a possibility to come over and see my family. [laughter] I would come over and do the interview, then I would go up to Connecticut and see my family. But I was in Baltimore for about two days, and they were showing me around, and it all seemed compelling. I told them there was no way I could even entertain this job without getting my wife involved conversation. They said, "Well, we'll fly her over in a couple of weeks. We'll have you both over." [Spurgeon laughs] This shows you how times were different for newspapers.

In the interim I approached

The Economist, and said, "Look, I've been offered this thing." The art director at

The Economist at the time said, "You know, there's this brand new thing called The Internet. It's possible that you might be able to send your cartoons for

The Economist from Baltimore." Suddenly this whole prospect became more tantalizing. So my wife and I took the job with the idea that we were going to come over for two years: give the kids a new experience and test it out a little bit. That was 25 years ago.

That was a long answer, by the way.

SPURGEON: In

SPURGEON: In CR

Holiday Interview parlance, we call that "a shorty." Perfect size. [KAL laughs]

Kal, you have something of an outsider's perspective on the whole field, I would imagine, given your range of clients and how your career started not in the US. You also knew about the Internet very early on. Is there a point at which where you began to see -- even if it was years away -- that there might trouble forthcoming for the way newspaper editorial cartoonists functioned, and maybe newspapers more generally? Certainly 1988 was a different era.

KAL: There was a bunch of things that I did notice early on. The first thing I noticed as an outsider coming into American political cartooning is you'd come into these AAEC conventions, and the cartoonists were kings. They were kings within their own newsrooms. The conventions were bordering on decadent, I thought, as an outsider coming in. I thought, "Wow." I thought they treated cartoonists so well in this country as compared to my experiences in the UK and Europe. But then you always thought in the back of your head, "Do these guys deserve it?" And "How long can we keep fooling everybody that this is what we should have?" [laughter]

Where this first came into play for me was when I was president of the AAEC in the mid-'90s. When you're president of the organization, you're responsible for the convention, which means also raising money. You were the ambassador-advocate for the industry. What I found in the decade between when I joined in 1986 and in 1996 when I was president is that the stature of the cartoonist in the newsroom was diminishing. Newspapers themselves were struggling, and that was before the crap really hit the fan. You could already see that syndication numbers were going down, and that people were struggling. You could see we had less to stand on as professionals in our field. In journalism.

The second thing is that I could feel within the

Baltimore Sun where I was working, I could see that budgets were getting tighter all the time. I was in a fairly unique situation. The

Baltimore Sun when I arrived had two newspapers. The

Evening Sun and the

Morning Sun. Like so many evening papers, it eventually bit the dust, and the cartoonist for the

Evening Sun was a very competent fella by the name of Mike Lane. He joined the morning newspaper because we were a union shop, which meant that because he had seniority over me if they had to fire someone they would fire me. They didn't want to do that, so they found a way to keep both of us on board. We would alternate days... we had some arrangement that fit both of us.

My boss, who was the editor, I was getting a lot of information from him about how budgets were being cut, how editors were fighting to keep cartoonists because publishers just didn't see the value in them anymore. Not like the old days. So I started to feel that.

My favorite story about when the Internet started coming around was in the late '90s. The

Baltimore Sun had the URL "baltimoresun.com." They bought it fairly early on, and they could have used it from the beginning. They use it now. But they didn't use it for the first five or six years because they were afraid if they had that URL that readers would choose to view them on the web rather than buy the newspaper. Now, it's the complete opposite. They

want people to find them easily. But they didn't want that at first. The URL they used was intended to drive people away -- like putting their fingers in the dike. [Spurgeon laughs]

Another thing was that in university I did animation. I'm a huge fan of animation, and I'm a huge fan of the potential it offers us collectively in the realm of visual satire. I'm convinced of its future and dynamism. For years when you're a cartoonist at a newspaper, and

the satirist in your community, every aspiring comic writer, drawer, comes and sees you. I'm delighted to meet these young kids and give them encouragement. In the mid '90s,it became apparent that anyone that wanted to become an editorial cartoonist, there was not going to be opportunities in newspapers anymore. It was becoming so small. So I kept on telling people to pursue animation. You need to look at this, because that's where there's going to be money. That's where there's going to be hope and possibility. So the more and more the web became apparent, the more and more I became convinced that's where the possibilities were.

SPURGEON: You've been beating the animation drum for years now, and I was wondering how you see... do you see progress in using animation as an editorial cartooning tool? Are there people using it the way you thought they would be by now? Is it far along as you thought? I mean, you sound

as bullish as ever.

KAL: Yep.

SPURGEON: So I wonder, then, why you think we're not further along in its ubiquity, why there aren't more people using it as a matter of course, in addition to why you're still so positive.l

KAL: I postulate that at any time we are ready for an explosion, and it's a little bit like this: I remember -- and you probably remember -- what it was like before

Doonesbury. Nobody could dream that a comic strip could be political. It wouldn't enter anyone's mind. It came on board as a curious collection of coincidences, but it happened and it changed the course of comics. You and I also remember what it was like before Jon Stewart on TV. When satire on TV was pretty pathetic. No one thought you could do that. Again, a bunch of coincidences came together and you have this amazing institution that modern democracy couldn't do without.

I think there will be something that can do the same for political animation. Something that if done right will capture the imagination of a large part of the public, and be extremely powerful and influential. There's one reason why I believe that, and several things holding it back. One reason I believe it is that I saw first hand how

Spitting Image, the puppet show in the UK, did -- I think they only ever reached about 75 percent of their potential, but they had a great thing going. It was amazing how that penetrated the culture, and how it was talked about. It was the most talked-about thing for several years in the UK. It was massive. I know that something not exactly like that but that involved good satire, good caricatures, good writing, put together on a timely basis, would be very effective.

Some of the reasons we're still being held back is due to technical difficulties. One is that to do it right, it's going to cost some money still. And whether you're doing with Hollywood or with the web, investment is something that's uncertain is going to be a bit tricky. The kind of technology that would allow this to work involves some of the 3-D animation you're seeing in TV shows abroad. In French Canada there's a pretty good weekly satire show called "God Created LaFlaque" [

Et Dieu crea Laflaque]. It's been on for about four or five years. It's headed by an editorial cartoonist who does the show -- it's popular, they have a great production pipeline. They show you can do it on a weekly basis. There's a show in France that works on a similar basis. I know you can find in South Africa and other places people doing the same thing. I'm just waiting for us to do something that will be really good.

It's expensive. In 2008 I pitched a TV show to Comedy Central, with a production team that I put together in Hollywood. We got pretty high up on the ladder in the discussion of making this thing a reality. The problem is that places like Comedy Central are used to animation on a

South Park budget. That's pretty low. We were low for the kind of stuff we were offering, but we weren't that low.

Now we're moving towards Hulu, and other on-demand stuff, so the 22-minute show won't be a necessity. The future will be a webisode that will be two- to five- to seven-minute shows that can be woven together into longer shows. And I think there's still some strong possibilities out there.

SPURGEON: You mentioned caricature as a positive just now.

SPURGEON: You mentioned caricature as a positive just now. Doonesbury

is an interesting contrast for what you do, Kal. You were in school during its sensational phase, and that's almost an anti

-caricaturist comic, because he relies on his cast of characters rather than graspable visual approximation of real-world figures. You, though, your caricature skills are a core strength, and have carried you throughout the course of your career. That becomes hugely evident when you read Daggers Drawn

.

Do you feel like you have to defend the art of caricature as a core value? We live in a kind of Doonesbury

/South Park

world in terms of the craft of visual satire. But you can't fake caricature.

KAL: No.

SPURGEON: Do you feel like caricature is at the heart of what you do, that it's at the heart of what you do?

KAL: Caricature is a great passion of mine. I feel caricature is at the core of satire -- it's a satirical art form. It's also one of the forms that it utterly and totally unique to cartoons. If you want to find something that's special to our craft, that sets us apart from Jon Stewart and these other things, these other people who work in the world of satire, caricature is something that belongs to us.

I love caricature, and I appreciate its strength and vitality. But I don't see those who do caricature in competition with those who don't. The reason I say that is because it's hard to be a caricaturist. Not everyone can do it. It's the same as doing jazz. Not every musician can be a jazz musician. I remember being at a concert with a classically trained guitarist. He was on stage with a jazz guitarist. They were asked to riff together, and the classically trained guy couldn't do it. It wasn't in his DNA. The same thing with caricature. Not every trained cartoonist can do it. But that's not slight on them. Some cartoonists are fabulous writers, and bring something else to the table -- that, of course, is the strength of

Doonesbury.

Because caricature is so strong, so potent and so effective, I feel if someone can't utilize it they're missing out on a great opportunity. It kind of makes their job a little more difficult. It's like having a great clean-up hitter -- it's a great thing to have in your tool belt.

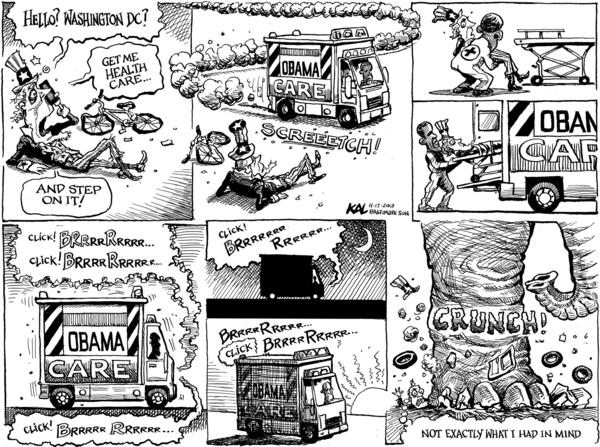

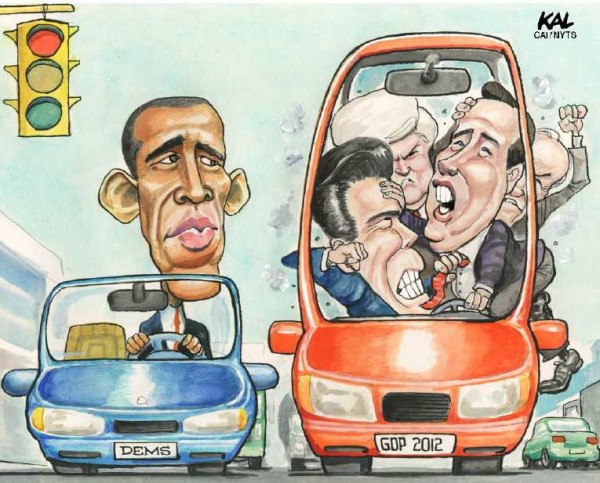

SPURGEON: One thing I think distinguishes your skill as a caricaturist -- and this might be the animation background -- is that you do a nice job with they

SPURGEON: One thing I think distinguishes your skill as a caricaturist -- and this might be the animation background -- is that you do a nice job with they physicality

of your characters, their movement and the way they stand. I'm not sure I see that with some caricaturists that concentrate on facial appearance. I thought your [President] George W [Bush] was very funny in this kind of ex-jock slouching he would do. There's a [President] Obama cartoon you reprint in Daggers Drawn

where he is about to run the gauntlet of healthcare reform, and the way he's standing is funny -- the perfect student. Is that the animation background, Kal?

KAL: Yes. I remember one fella I used to show my cartoons to to get feedback. This is early in my career. He made a point that in my early cartoons that if you started in the middle of the nose of the face the further you got away from that point the weaker the cartoon got. Because I was putting so much emphasis on the face. You realized that caricature goes throughout the whole body -- this is true of animation, too. It's like being a mime artist. It's like being an improv actor. You can signal so much to your audience in terms of emotion and possibility through your entire character. If you don't utilize that, you're missing out on a great opportunity.

When I'm doing my cartoons, what I'm trying to with whatever gag I'm creating as a metaphor, I want to milk every opportunity to help deliver your joke. It's like being a good actor. You hand a joke to five people, the first four will blow it and the fifth will make it sing. It's because the delivery is so important. In the case of a political cartoon, you want to deliver your joke as best you can.

I do want to make a point about caricature, and I've found a few other colleagues who think this exact way. In fact, I met a great Australian cartoonist recently who does the same thing. When I do a caricature, I don't look at a single photograph and try to copy that photograph. I never think of that person in two dimensions. I think of them in three dimensions. I draw a face; I'm building a face. A shape I'm putting on a Mr. Potatohead. I know I have a face down well when I feel I can draw them from three-quarters behind, like I'm looking over their shoulder, without a photograph. Because I know the structure of their face so well I can turn their head in my mind and see those features.

SPURGEON: One thing the Daggers Drawn

book did for me is remind me how varied the structure of your cartoons runs from installment to installment. You can do single-illustration cartoons that are very direct and lean, you can do single-illustration cartoons that have a lot of chicken fat to them, where there are jokes and visual asides to them. You're also a fine multi-panelist cartoonist, working in a Sunday strip form, where your line becomes a bit more spare. I wonder about the variety. Is that you finding solutions cartoon to cartoon? Is that you just staying interested? Because I can't think of a KAL rhythm, a KAL structure. I think of the variety more than any one format.

KAL: I do it for a variety of reasons. I think I started it more when I was with the

Sun, when you're doing daily stuff and talking to your audience regularly. The whole time in this job, we're having a conversation with our readers. We're not standing on a soapbox preaching. If that was the case, our readers would stop listening to us really quickly. We're having a conversation. You have to engage them and just like with any friends and relatives, if you speak in the same way every time you will bore them, and you will the pants off of yourself. Partly as a way to keep me entertained, but also to maximize my effectiveness as a communicator, I wanted to learn all of these different approaches. Find whatever subject would speak to me and then match it to an approach that would suit it. Furthermore, I wanted to be surprised. I wanted every time that someone opened a newspaper they didn't know what they would get. They'd be surprised by choice of subject matter.

In the case of

The Economist, it would be mixed geographically, so it might be Asia this week and Europe the next. Mix it up according to your temperament: hardassed to funny. Mix it up in terms of use of large single-panel with elaborate caricature... you would try to make yourself a virtuoso in all of these things to make your work as effective as possible.

It's probably an approach to skill set I learned playing basketball. I played fairly high-level basketball, but as you know I'm a five-foot-nine guy from suburban Connecticut. In order for me to play at that level, I was never going to be the fastest, I was never going to jump the highest, and I was never going to shoot the best, but I could try to be good at a bunch of different things, and that would make me valuable. The same way with cartooning. I always figured someone might be able to write better than I can, so I wanted to have as many high-level skills as I can. The curious thing was to put together a book of

The Economist stuff. The

Economist audience is much more sober than the the audience for the

Baltimore Sun. It might be more sophisticated. I was surprised by the amount of comic, lighthearted stuff over the years. It was in part because when I joined

The Economist, they didn't want that stuff

at all. They were dead serious. I think over time I introduced a lot of humor to the magazine. I think it's now become part of their trademark look.

SPURGEON: Do you not sign your work for The Economist

? A friend of mine was presented with some of your cartoons, and couldn't recall your name, but thought they could scan for your signature but told me there was none to be found.

KAL: That's right. Nothing is signed in

The Economist.

SPURGEON: But you are a prominent person with the culture of the magazine. It seems like they value what you have to offer. Is it a good relationship that way?

KAL: It has evolved into a really nice relationship. When I was first with

The Economist, they were a small, niche publication. About 300,000 circulation worldwide. Now that number is creeping up to two million. They have an enormous international brand that they certainly didn't have when I started. But you're not allowed to sign anything. I remember that after I'd been there a few years, I'd been offered jobs with other publications and I was thinking of quitting

The Economist because one of the things was you can't sign your work, and when you're young and starting off you want to get your name out there. But in time... it was a great wave to catch with

The Economist. They took off and I became part of that great explosion. My work became a signature of its own.

When I first came on, there was resistance to having a cartoonist at

The Economist because it meant that I stood out more than the other writers. When I started doing political cartoons for them that was another case -- the

Economist speaks with one voice, but they have this other guy and he does his own thing. On their web site, they credit me. I have a signature, and I have my own section. And so I am getting a name. They use me as an ambassador for the publication, even though I've never been a staff member. It's an amazing experience. I'm so proud, and flattered and honored, to work with them.

SPURGEON: Your relationship with that publication is often held up as a model for how folks can use a cartoonist. Is it really just a confluence of factors that have made that one work. Why aren't there more of you, Kal? Why aren't there more single cartoonist/single publication relationships of note?

KAL: One thing is that I've honed an ability to communicate in public. I'm a good ambassador. I can do performances. I can go out and speak. All of that works much to my favor. The publisher commented once that the only time

The Economist gets a standing ovation is when KAL on the stage. [laughter] I do lots of fun things for them. That's really helped a lot. We do have some cartoonists that are doing public performances. I think that helps. I know when I was at the

Baltimore Sun I would give weekly talks all around the regions -- whether that's at a school, or a pensioner's home, things like that -- so people not only grew up reading my cartoons, they've actually met me. In some ways that elevates your presence. You might be the most recognizable person at your paper; you can be a media star if you manage it correctly. I think that really helps a lot.

Tom, you might be a better judge of this than I am, I think my cartoons -- even if you don't agree with them -- I think they're approachable. I think people respect the artwork, respect what I'm trying to do. I think that helps a lot. When I do my cartoons I try and honor my audience by investing a lot of time and energy into my artwork, by giving them a lot.

SPURGEON: That seems like a general value for you, Kal. You seem like an "added value" guy. Is that just your personality? Are you very concerned with distinguishing yourself in a marketplace? Is that a basketball value again, were you the guy who picked up towels off the bench? Or is that just smart business.

KAL: A little bit of both. I so value that piece of real estate I'm given. I had to work really hard to get it, both at

The Economist and at the

Sun. I realize how incredibly lucky we are in our craft to have someone pay us money to read the news and draw and connect with people and do all this cool stuff. I'm going to put back twice as much to make sure I bring honor to that space.

One thing I remember from early in my career [laughs] when I was working at the

Observer, a newspaper there. There was a cartoonist there who was quite good. He was the senior guy; I was kind of the new kid on the block in respect to cartoons. He would stroll in on Friday at two in the afternoon, finish at five, kind of whip off his cartoons, get paid a fair bit of money, and people would see him at the pub in the evening. The journalists would all grumble. The way he drew looked like he drew it on the back of a napkin. They basically showed him no respect. I wanted to make sure if I'm going to do my job, I don't want to be the first person to leave the building. I want to prove to these people that what I do is worthy of what the other journalists do. I always wanted to make sure that in any editorial meeting I could hold my own with anybody on any given subject. That took a lot of work. I knew my job was vulnerable, and I wanted to do everything I could to keep my job. That was my motivation.

SPURGEON: You're fairly even-handed, too. You engage a variety of subjects -- you haven't shied away from anything, but you also don't have a signature subject. So is there a stand on an issue about which you feel pride? A specific issue or a general take that you feel happy with, looking back?

SPURGEON: You're fairly even-handed, too. You engage a variety of subjects -- you haven't shied away from anything, but you also don't have a signature subject. So is there a stand on an issue about which you feel pride? A specific issue or a general take that you feel happy with, looking back?

KAL: I think there's a few. The first one that comes to mind is the Iraq War. I was a strong, ardent opponent of it from the beginning. Bush made a speech at West Point and it was the first time he had made reference to a proactive invading of countries. [laughs] I thought that this was an outrage and that something was cooking. I took a lot of heat in the early days for my resistance to the build-up to the war. I was against the first Iraq War. I was against the way they were packaging it to fool the American people as to the whole purpose of the undertaking. There was a case to be made for getting rid of Saddam, but they were trying to phrase it as something it wasn't to get more people on board. I took a lot of heat for that.

The Economist was in favor of the Iraq War. Finally, they came around.

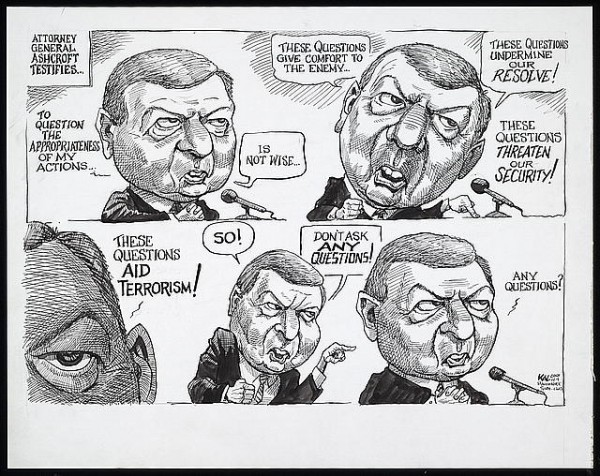

[The Patriot Act...] there were a lot of people screaming on both sides of the aisle when this thing was being written. Attorney General [John] Ashcroft was basically in hiding while pulling thing together. Everyone also knew that whenever this came out, it would basically be rubber stamped and thrown in. No one knew what was going to be in it. So they couldn't wait to get more information. Ashcroft finally agrees to appear... I think it was front of a Senate judiciary committee -- I forget which committee it was. He opened with a written statement that was like two paragraphs long. I used to carry that statement in my wallet it was such an outrageous thing that he said. It was long the lines of "to questions my actions, my motivations, in this area is to aid the enemy." So basically "don't ask me any questions." When I heard this I was so outraged, because I thought it was not only my job as a journalist and a commentator to question the actions of any public servant, it is the responsibility of every citizen to question them. I did a very strong cartoon on that day. While I was doing that cartoon I felt very sad for our society... feeling how crazy the the environment was in the country at the time, I though more people would support him than not. I did this cartoon, and I though I'd be barraged the next day with e-mails and phone calls from people against it.

So I did the cartoon. The next day rolls around. There are no phone calls or e-mails. There are no faxes. I look around at my cartoon colleagues around the country and they're also doing a lot of cartoons berating Ashcroft. Along with politicians on both sides of the aisle. I was so relieve that at that moment our society had protested. We had passed the test, if you like. I know we'll be tested again.

Fast forward two or three years. The library of congress is putting together an exhibition about 9/11 where they gathered a lot of tidbits: stories, photographs, memorabilia, and other important stuff. They asked for about a half-dozen cartoons and that cartoon was one of the ones they wanted to have for the show. I was very proud of that.

SPURGEON: We've talked about the shifting nature of satire... the shifting nature of politics itself, the hyper-media awareness that politics has and how this and other factors have exacerbated the banal aspects of public discourse. I remember talking to someone... an editorial cartoonist, I think... and we were trying to figure out why the last election wasn't great for editorial cartoons. Was there something missing? Is there something different about the field now? Do you have any thoughts about making work in this political landscape? Our political process' orientation is so different now than when you started. Do you find it changes the way your work is read?

KAL: This is also I guess part of the demise of political cartooning as we know it, where the content applies. Because... it's all about audience, and who's reading them. On the days -- to pick the

Baltimore Sun as an example -- where the market penetration of the newspaper in the neighborhood was so strong, you know if you did a cartoon it was going to be something this many people would say, and it would have the chance to become an objective conversation. The politicians would have to pay attention to that. Our presence has been so diluted that even if you do a great cartoon no one is going to be reading it; the best you can hope for is being picked up by

USA Today in their weekly round-up. That's no place to be a kind of thing where you can be effective. This is a really big difference that's we've seen in the last decade, and every four years it's going to get more watered-down. There's no question. Particularly on anything national. Let's return just for a second back to that's where the difference with the animation can be. It has the potential to capture a larger group of people's imagination. That will be the next place where visual satire will be able to have an impact on the conversation, in my view.

What happened is we had to consecutive campaigns where they lasted from month to month to month to month to month. So the story got dragged out. When you're talking about a singular great cartoon or series of great cartoons, I like to compare it to your classic baseball metaphor. It's the World Series, seventh game, two outs, bottom of the ninth, bases loaded, you're coming up to bat. You have all the elements for history right in front of you and you have the opportunity to hit the home run or whatever. But that rarely happens anymore. These days there are so many elements in the news constantly changing and going around. The audience is now also so incredibly visually sophisticated. In the newspaper, the cartoonist has to compete with your own weather map! [laughter] That's not even to mention the Web. Or you can go to CNN for five minutes and you're in graphic overload -- your eyes can't take it anymore. Every special effect you see in every movie. The cartoon as a visual almost can't compete, unless you have the capacity to do something really special. What the cartoonist has to offer is this strong mix of good journalism, satire, and innovation. We can't rely on the same tools anymore. They're just not as interesting to people. We're working with an old tool set, and the news is getting spread out over a longer period of time, and you have the dissolution of the audience. Those three things are conspiring against us.

SPURGEON: You're coming up on two years since your return to the

SPURGEON: You're coming up on two years since your return to the Sun

. I remember when you went back, but I'm not sure I know how it's gone for you. Has your second stint with the Sun

been tailored to the views you have about how that relationship, that kind of venue, works best? How much of how things have been tailored to you encompasses the different role that cartoonists must play now?

KAL: First of all, it's been extremely interesting being back. And a whole lot of fun. Part of it is the very great satisfaction is that the people are so delighted to have a cartoonist back they really feel the value a cartoonist brings to the newspaper. Whatever remaining audience the

Sun has, they also love cartoons. You can feel the love. That's the first thing. The second thing is you can feel the local politicians... trembling isn't the right word, that's overstating it, but they are now watching very closely. When you're a cartoonist in a local newspaper, you're the only satirist in your community. These guys, they get nervous by what you can can do to them! So that's been really interesting. Doing the local cartoons has been great fun. The newspaper has been showcasing me a lot. I don't know if you saw it, but just yesterday I did a double page spread -- this is a broadsheet, so two pages bigger than my drawing table -- looking back on 2013. It was a great thing. They want to commission me to do some animation. They want to showcase what I bring to the table.

For me, I'm glad I'm not doing it every day. You do it every day, you get kind of locked into this machine -- you're churning it out. This way I keep fresh, I'm doing other things. It's been a good thing all around. I also know that this could collapse and die in four months. The

Sun could collapse, it could be bought by someone that doesn't like cartoons. They could just run out of money. "Sorry, it's either you or having someone to do the toilets." [laughter] That could happen. So I'm just enjoying it.

SPURGEON: When I think of you doing all the outside activities for which you're partly know, the residencies, the Second City tour -- in fact, you just got back from overseas -- I think of that as being the result of that hiatus period, between when the Sun

let you go and before they brought you back on board Winter 2012. That you were forced to seek out different models for arranging your professional life, and without the Sun

, you also had time to pursue these things a bit further than maybe some of your peers. It seems like that time was spent well in terms of finding a new model for a cartooning career -- how do you look back on that period now? Because as mentioned, you've stuck with a lot of that stuff even with your core professional responsibilities shifting back to something that looks more like 1990-2005, at least from the outside looking in. Is it fair to say your efforts intensified in 2006?

KAL: It's fair. It is. Partly it was out of necessity. To give you a little background on how I left the newspaper. I told you before that for years I've been telling youngsters to go into animation. And the Sun was offering buyouts as they'd done... they'd offered a round of buyouts as other places as had done for several cycles. Every time a buyout would come, you might be offered a buyout, and you'd go through this ritual of talking to your boss, and saying, "Hey, should I really take this." I did this several times. They were always like, "Nah, we love to have you here." But this one year, when I went to go see my boss, she said, "You know, if you don't take the buyout, and we don't get the bodies we need, I might have to fire you." And I went, "What?" [laughter]

She said the dictate from the Tribune Company said that anybody's whose job doesn't cross with anyone else's job -- if somebody was laid off and this meant that somebody else had to do that job, that person was more valuable than someone who was independent like me. There was a guy in the next office whose job it was to open the letters to the editor and read them. His job was more invaluable than my job as the cartoonist because if he go fired somebody would have to do what he did! [laughter] This is ridiculous. So I went home... it was on a Friday. I had until Tuesday to decided whether I was taking the buyout or not. So I talked to my wife and I said, "You know what? Screw 'em." [laughter] "This is going to happen again and again." I decided I would take my own advice and go do animation or something. Fortunately, I had The Economist as a bit of a buffer, but I had to find a new way. I didn't know what the future was going to be. I would go back and live on my with the way I did when I first started. Go out in the world and try to make it.

I talked to UMBC, which is a local university here. I met with them on a Monday. Instead of saying, "Take some classes" they offered me a part-time position as an artist-in-residence. That's where I started, and then other things came along. It was just piecing stuff together. I was delighted that it happened. It happened at just the perfect time... basically, I was one of the first guys to lose a job. I know that among my colleagues when they heard that I was dispensable, that meant that anybody was dispensable. That turned out to be true, of course.

SPURGEON: You kickstarted the

SPURGEON: You kickstarted the Daggers Drawn

book. This was totally crowdfunded.

KAL: True.

SPURGEON: How did you control your impulse not to overdo a project like that? I know that's a problem with crowd-funders that are well received like that one was.

KAL: We put a lot back into the book. The book was an extension of the philosophy I bring to this stuff. If I was going to do a book, I was going to do it 110 percent. I was going to do it the best I possibly could. Little did I realize I would get the money that I asked for. I thought I'd be luck if I got $20,000, if I got $25,000. To get $100,000 was such an astonishing achievement, I felt now I had to honor all of my backers, and I was going to deliver something special. So at the end of the day -- I reached $100,000 but with the book and the postage I probably spent more than that on the whole project. I'm now selling book to get back some of what I spent altogether. That kind of fits into everything. I wanted to do something special and I hope people appreciate it.

SPURGEON: One thing that's interesting about your career is you've always published. You published a few books from your first run at the Sun

. You've done a ton of shows, as I recall, too. You're going to do more animation... you've done animation. So you've worked in a variety of formats, in a half-dozen contexts. Is there one that feels more natural to you than others. Is the core of it still seeing the Sun

cartoon, or something in The Economist

? Do you even think in terms of format anymore or venue anymore. Once your work is all over the place, do you value them differently? Are all of these satellite to a core expression.

KAL: Boy, that's a really good expression. Part of it --

part of it -- is that variety is the spice of life. I like have these different types of thing. It's kind of cool. No question. What I think... I'm going to take us back to 2000. The election 2000. Where a group of several hundred voters turned an election for George W. Bush. That to me is an historic election. The country and the world might be a different place if George Bush wasn't elected. For a start, we wouldn't have invaded Iraq. That's not to say Gore would have been a great president, and there's a lot of movements going on in the world which would still lead us to where we might be now. But it was an historic election. I'm sitting here in Baltimore doing cartoons for my audience. My audience is all going to vote against George Bush. I would have done

anything to be working or at least have the ear -- or the eyes -- of about 2000 people in Florida for three months. To try at least change their mind and affect what turned out to be an amazing turn of history in my lifetime.

To me the prospect that in some way, that maybe through what I do in my medium that I could affect history in any way? That still to me has to be one of the prime goals in your doing this. Sure, this is terrifically satisfying. Sure, I've been luck to have live in an exciting, diverse world and meet so many interesting people, but at the end of the day what you want to try and do is with whatever powers you have at your disposal, you want to try to make the world a better place. I sound like freaking Miss America. [Spurgeon laughs] But it's true. If you can do it, that's what you would like to do. I still believe in our craft, the craft of satire, that that's still possible. And in ways hopefully -- I'd like to hope -- I can be in the in the forefront in some way of trying to bring us into the next generation of visual satirists. If I could do that, I could feel like I was making some sort of contribution to the bettering of public discourse, if you like. So that's what drives me. I do get the satisfaction that you pointed out of reading the cartoon in the paper, being in The Economist. Getting a lot of views on Facebook or whatever. The feeling that your stuff is out there. Those things give me a charge, they really do.

I love the traveling and helping other young cartoonists, too. So there's still a lot to be done, if you like. But at the end of the day I feel like I'm still a political animal... I'm going to say, I'm afraid it's going to sound a little profound, but I feel it's true: there's a lot of bad guys out there, and it takes a lot of good people fighting, you have to fight to retain your freedoms, you have to fight to right the ship. You have to fight to point our lives in the right direction. Because if you don't do it, some jerk is going to take it the other way. It's part of participating... taking some responsibility in making the world a better place.

SPURGEON: I can't think of a better ending than that, Kal, although I'm sure I forgot to ask something. Is there anything else you wanted to mention?

KAL: This summer, in June, July and August... I'm going to be an artist-in-residence in Bermuda.

SPURGEON: [laughs] Well, of course you are. [laughter]

That's like a made-up gig. That's not a real gig. Come on. That's like a 1985 Robin Williams movie.

KAL: [laughs] The reason I bring it up is that there's a little more to it than you'd think. The deal is this. It

is an artist-in-residency, but unlike a lot of these things, they don't pay you. They give you a visa for three months, they give you a small apartment, and they give you a bus pass. You have to produce work -- you have to give them a proposal. At the end they have an exhibition in the island museum and you try to sell your work at this exhibition and hopefully this covers the costs while you're there. For your average artists, it's a bit of a risk. You have to give three months of your life, you're paying for your own food and everything because you're not making any money. In my case, I can still make my cartoons for

The Economist and

The Sun. So I'm better off than most folks.

Here's the deal. The proposal I made to them... having done a fair amount of travel and knowing that any time as a visitor or as a tourist you get a completely superficial view of the place you're touring. I figure that as a commentator and as a journalist, if I'm going to go to this island, I'm going to want to be wearing those hats -- that's my strength and that's my passion. So I told them what I'd like to do is go and do a bunch of itnerviews -- I want to get in depth interview with folks. Chat them up all the time. I want to interview everyone from the garbage man to the prime minister. Then I want to do 20 cartoons from the perspective of each the twenty different people. I'm their eyes and their mouth and their soapbox.

SPURGEON: Nice.

KAL: Then when I'm at the end of my three months, at which point I'll probably have cabin fever, I hope to make some cartoons that make some sense of my experience there, be able to portray it in cartoons. I think this might peel away the veneer of the country, and get some interesting conversations going. I'm much more interested in doing that than sitting and doing watercolors or something like that. I think that's going to be really interesting. It could get a lot of attention.

SPURGEON: Not ruining this for any other cartoonists I think is the important thing, Kal. I think can I speak for your peers there. [KAL laughs] If you poison the Bermuda well, you're going to get a lot of attention and none of it good.

KAL: [laughs] I think there will be a lot of opportunities there. I'm looking forward to it. I'm going to see how it unfolds. It will be a good challenge. [pause] An adventure.

*****

*

Kaltoons

*

KAL At The Economist

*

KAL At The Baltimore Sun

*

Daggers Drawn

*****

* cover to new work

* self-portrait

* color work I like

* KAL's most famous contribution to satirical animation, I think; it's the one I remember

* a number of caricatures in one cartoon

* President Obama's body-language here made me laugh

* the Ashcroft cartoon

* one from the recent run of

Sun cartoons

* an

Economist cartoon

* on George W Bush]

* another color piece I like (below)

*****

*****

*****

posted 4:00 pm PST |

Permalink

Daily Blog Archives

November 2019

October 2019

September 2019

August 2019

July 2019

Full Archives