December 31, 2010

CR Holiday Interview #11—Daren White

CR Holiday Interview #11—Daren White

*****

I know of

Daren White mostly through his stewardship of the Australian showcase-style anthology

DeeVee, which had a proud, sustained run near the end of the lifespan of serial alternative comic books. He's also known for his collaborations with the cartoonist

Eddie Campbell, in the

Bacchus comic and on the stand-alone works

Gotham Emergency (published in

Batman: Legends Of The Dark Knight #200) and

Batman: The Order Of The Beasts. I wanted to interview him in this series for his writing of the graphic novel

The Playwright, jointly published by

Top Shelf and

Knockabout. Lushly drawn by Campbell,

The Playwright seems to me the kind of book that is the lifeblood of comics' particular flowering as an art form: original work that is richly conceived and ruthlessly executed, with no tie at all to a media property or a prominent social issue. I worry that there are so many comics of so many kinds out there right now that books like

The Playwright, with its attention to small moments and fealty to a slightly cockeyed perspective, may be easily brushed past for more sensational work. I greatly enjoyed exchanging e-mails with White, and hopefully we can convince you to give his book a try. -- Tom Spurgeon

*****

TOM SPURGEON: Daren, one thing I saw reading other interviews is your statement that you're all pretty much done with

TOM SPURGEON: Daren, one thing I saw reading other interviews is your statement that you're all pretty much done with DeeVee

, the magazine where a few chapters of this work were initially serialized. If that's a closed chapter, how do you look back at the publication and its legacy? Did it do what you hoped it would when you started? Was it a worthwhile experience?

DAREN WHITE: I'm reasonably happy with the legacy of

DeeVee although, I suspect in common with any creator looking back, some of the stories might not have aged too well. I'm proud of the fact that we kept to our publishing schedule, being quarterly for two years and bi-monthly for a year and, overall, think the quality trend was upwards. I tend to remember that time as the panic publishing period. Many midnight phone calls to overcome the time differences between Australia and pretty much the rest of the world. The three annuals, 2001,

Molotov and 2007, reached the standard that I, personally, hoped we'd reach. I think they hold up well. But of course by then we'd blown the schedule. I'm happy that we provided an internationally distributed vehicle to Australian creators, at a time before online exposure was easily available. I do remember that period fondly.

SPURGEON: I think that in the broadest sense possible we're all familiar with the character type you put front and center in The Playwright

-- the rough outlines, anyway -- but I wondered if you could describe what you found compelling enough you wanted to devote this kind of creative energy towards delving into this particular person.

WHITE: I was struggling, at the time, with the honesty and perspective required to produce even half decent autobiography. I wrote the first chapter for my own amusement, almost as an antidote to a story I had serialized in

Bacchus, and abandoned incomplete. I was toying with writing something about the television playwright

Dennis Potter (

Brimstone and Treacle,

Pennies From Heaven,

The Singing Detective) whose real life sometimes appeared stranger and more tragic than his frequently strange and tragic works. Those ideas merged with a third notion of a character type that was very successful in their chosen field whilst being hopeless in every other facet of life. The various ideas gelled and resulted in a character who was, hopefully, more complex than the stereotypical unpleasant, loser style character that he might appear to resemble on the surface. I quickly settled on the conclusion as it appears in the final book, and then worked a plot towards it, whilst exploring the relentless mental narration within the characters head. Knowing how things would conclude gave me the freedom to ramp up the cringe factor at the start. I also got to channel my inner child and use lots of toilet humor.

SPURGEON: This may be an impossibly tedious question, for which I apologize, but can you describe how the work came to be as a stand-alone book? How does this final work resemble the work that you yourself pursued art chores on at one time? Also, am I right in thinking that the work shifted a bit conceptually when you went from the serial chapters and into this final single-volume work, and if so, how so?

SPURGEON: This may be an impossibly tedious question, for which I apologize, but can you describe how the work came to be as a stand-alone book? How does this final work resemble the work that you yourself pursued art chores on at one time? Also, am I right in thinking that the work shifted a bit conceptually when you went from the serial chapters and into this final single-volume work, and if so, how so?

WHITE: My own illustration of the early pages, only one of which was published (in

DeeVee #14) quickly tipped me off that I'd need a collaborator. I showed the script for the first chapter to Eddie and he liked it enough to offer to illustrate it. I still joke that had he realized it was the first chapter of a longer work, he probably would have kept quiet. He illustrated three of the ten chapters, which appeared in black and white, in

DeeVee over a six-year period. Mentioning that makes me question why I never gave it away, but

Chris Staros later assured me that many a decent books has taken ten years to complete. I still hold a glimmer of hope that

Big Numbers will one day continue. By the time these chapters had appeared I had a detailed plan for how the story would play out, and had arrived at the ten specific chapters that we adhere to in the final book.

After the last

DeeVee I did flirt with the idea of serializing chapters in other anthologies, but nothing definite was agreed. I continued to write the scripts but didn't feel it fair to take Eddie away from paying work for something that was effectively on spec. Two of the existing chapters then appeared online at

Modern Tales and were re-formatted into single tiers, resembling a newspaper strip, to better present on a monitor. A consequence of this was that Eddie and I much preferred the material presented in this format and so subsequent pages were produced in this format. Eddie continued to add pages over the period in which he produced the

three,

color books for First Second, until we finished the bulk of the story. Eddie decided to color the pages and actually photocopied the originals onto watercolor paper, stretched them and painted over the existing artwork. He added far more background detail and generally added texture and richness to the imagery. The conceptual change in the story, around the halfway point, was intentional and planned rather than a result of the way it was then being produced. Although it had its genesis in a short story, it became a complete story in my mind, pretty much as published, quite early in the process. We agreed to a co-publication deal with Top Shelf and Knockabout in 2008, and finally saw print this year. Phew.

SPURGEON: [laughs] I was intrigued by some of your structural choices and I wondered if you could describe the reason you went in the general direction you did one some of them. The three-panel sequences I assume are to make it resemble comic strips rather as opposed to a series of comic book page, but why was that preferred? Was there something in the quick in and out structure that you were hoping to employ on your story's behalf? Also, is there a reference to which maybe I don't have natural access in terms of your telling the story via outside narration?

SPURGEON: [laughs] I was intrigued by some of your structural choices and I wondered if you could describe the reason you went in the general direction you did one some of them. The three-panel sequences I assume are to make it resemble comic strips rather as opposed to a series of comic book page, but why was that preferred? Was there something in the quick in and out structure that you were hoping to employ on your story's behalf? Also, is there a reference to which maybe I don't have natural access in terms of your telling the story via outside narration?

WHITE: As I mentioned before, the three-panel structure came about after the book was started but seemed obvious once stumbled across. As well as the resemblance to old newspaper strips, the outside narration was also used in old English comics aimed at young readers (things like

Look and Learn). I wasn't trying to riff on these directly but they added to the sense of England that is intended as the setting. The narrative voice is supposed to be 1950s

BBC newsreader English. I wanted a matter of fact reportage of the scatological humor and sex, to make the whole thing more absurd. Features such as adjectively describing, rather than naming, the characters were experiments that seemed to work and were retained for the duration.

SPURGEON: Why was the work set where it ends in the 1990s, as opposed to the present day? Was it just that you were interested in certain societal elements that were locked into certain time periods, or is there something about the Playwright's adult life being lived in a specific time frame that you think is more poignant or meaningful than if the last pages were set in 2010?

SPURGEON: Why was the work set where it ends in the 1990s, as opposed to the present day? Was it just that you were interested in certain societal elements that were locked into certain time periods, or is there something about the Playwright's adult life being lived in a specific time frame that you think is more poignant or meaningful than if the last pages were set in 2010?

WHITE: I did plan the character's time line and wanted to reference specific historical events. I wanted the character to carry out his national service during the period in which Britain stopped clinging to the idea that it was still an influential Empire. Roughly around the time of

the Suez crisis. This established that the story roughly concludes in the 1990s which fitted my idea that the character was always slightly out of date. A decade or so does not seem materially different to the present but in the details things have changed. The computer he purchases to keep in touch with modern technology is already hideously dated to the current reader. Hopefully this subtlety gives pointers to the reader.

I think that time gap is also the period at which nostalgia starts to cloud our memories. I migrated to Australia in 1994, and so my recollections of England are already skewered by nostalgia. I tried to make the Playwright character nostalgic, in the present, for the life he might have had if key decisions were made differently. Eddie's color palette was spot on with this, accentuating the sense of the recent past. The color schemes for the early chapters remind me of visiting elderly relatives in 1970's London. The first watercolors he added were for the red London buses and we shared a sentimental moment about how distinctive that particular red remains in our memories. We quickly regained composure and went back to arguing about whose turn it was to buy the beers.

SPURGEON: What is it, then, that you wanted to say about nostalgia through

SPURGEON: What is it, then, that you wanted to say about nostalgia through The Playwright

? It's such a major force in so many of our lives -- and comics is almost soaked to the bone in it, from the act of reading comics themselves to all of the subject matter we ascribe to various times in our lives -- that I can't imagine you just have it in there as a kind of a floating loose idea. How does this character feel the effect of nostalgia, and how does his orientation change as part of the new life he settles into at story's end?

WHITE: I wanted to evoke a slight sense of nostalgia without it becoming a romp. Again, that's why it roughly concludes a decade and a half ago, rather than, say, 40 or 50 years. It was never going to be a story about the good old days. The Playwright character isn't overly nostalgic for the past. He can't selectively forget the bad bits because there'd be little left. Not because he had a miserable life, but because his life was so consistent, or flat. He had no real peaks or troughs. He is more nostalgic for a past he might have had. He doesn't

dream of being Batman, because he wasn't particularly weak or bullied as a child. He dreams of having a normal life, where he interacts with people and has friends. Where his parents gave him the same attention as his brother. As the story unfolds this

faux nostalgia drops away. The actual present becomes the place in which he chooses to live.

SPURGEON: Another structural question. How did you work in terms of the final script? Was a final script what you provided Eddie, or did you shape the individual pages as you went along via re-writes? I'm fascinated by the placement of the text, the proximity of words to individuals throughout the book. Was that all Eddie, or did you worry at all about the visual effect of the writing on the page?

SPURGEON: Another structural question. How did you work in terms of the final script? Was a final script what you provided Eddie, or did you shape the individual pages as you went along via re-writes? I'm fascinated by the placement of the text, the proximity of words to individuals throughout the book. Was that all Eddie, or did you worry at all about the visual effect of the writing on the page?

WHITE: It was a full script, both panel descriptions and narrative, with minimal rewrites. However, Eddie had complete freedom to design the pages and did drop or add panels to best serve the story. The times where the text seems to lose the imagery was deliberate, as I often wanted the two to tell different, but complimentary, stories. However Eddie often took this and created great sequences that were far better than I had originally envisaged. The panel repetition was also scripted from the start of the first chapter. This was intended to save time as the page rates offered by

DeeVee were a bit rubbish, and I thought he'd photocopy the panels and paste them down. Instead he enlarged them, often very much so, and redrew fine details to contrast the thick chunky photocopy lines. When he came to paint the pages he often added even more detail and so my cunning plan to save time actually had the opposite effect. There were a few instances where I did revise the script. I inexplicably changed the tense of a complete chapter. Eddie maintains I did this to see whether he was paying attention but I think it was due to the longish period since I'd written the previous chapter. Oh how we laughed about it later.

SPURGEON: One of the affecting ideas at work in

SPURGEON: One of the affecting ideas at work in The Playwright

is the notion of obsessions and creativity, that someone can swap out one set of obsessions for another, even sex, and that an obsessive approach to creativity may be a great contributing factor to a certain kind of sex in that field. It's not presented in a polemical way, but rather through the characters, so I wondered how close these thoughts are to your own?

WHITE: I don't subscribe to this theory myself but think it's plausible enough to be used in a black comedy of this kind. As mentioned, one of the ideas I wanted to explore when planning the story was that a particular personality could be wildly successful within their field but wholly incompetent at everything else. I think this is prevalent in certain sportsmen, certainly in Australia and Britain. People who are at the top of their chosen fields are usually obsessive because that's a fundamental component of their success. That they often prove to be disastrous with other aspect of their lives is what I found interesting. I've said a few times that, sexually, the Playwright has had a dry run of such magnitude that it couldn't result in anything other than obsession. However, I didn't intend to suggest that sexual obsession drove his career. It's simply one factor that he has used to his advantage. Another is that he's good at writing a certain type of story. He clearly also uses, say, family matters within the plays.

SPURGEON: This may be an overlapping idea, but one appealing thing about the Playwright is that he has this compulsive side to his character, that there are things upon which he acts -- if imperceptibly -- that are slightly out of his control, and that this is mirrored in his art by the constant way in which life circumstances find purchase in his individual works. How much do you think a certain kind of impulsive behavior is part and parcel of creative work, how much is reacting without that kind of control a younger man's game?

SPURGEON: This may be an overlapping idea, but one appealing thing about the Playwright is that he has this compulsive side to his character, that there are things upon which he acts -- if imperceptibly -- that are slightly out of his control, and that this is mirrored in his art by the constant way in which life circumstances find purchase in his individual works. How much do you think a certain kind of impulsive behavior is part and parcel of creative work, how much is reacting without that kind of control a younger man's game?

WHITE: I quickly surmised that a writer as insular as the Playwright would be using any life experience or interaction, however minor, within his work. He hardly had great moments of personal drama to call on. That was one of the conceits that I tried to mine humorously. The play titles such as

Tea for One and

Rainy like Sunday morning suggest almost tragically mundane source material. I think this is why a few reviews have actually questioned whether he is in fact a playwright, outside of his mind, at all. At the start of the book, he had a far more juvenile approach to life than his age suggested. This would manifest itself in his creativity, because, let's face it, that was his only outlet valve at that time. In terms of impulsive creativity in general, I think an idea is at its most exiting, for the creator, at conception. At that precise moment it has almost impossible potential, and that potential will usually fade, be replaced or, worse, suddenly be realized as unoriginal. Obviously with maturity, control over the use of these ideas increases. The ability to filter the good ideas from the bad becomes easier. I'm not sure if I've answered your question.

SPURGEON: How much did Eddie's obvious skill with color surprise you in terms of seeing your work in a different light? You mentioned in one interview that you found his work with textures to be a surprising thing; what do you mean when you talk about texture?

SPURGEON: How much did Eddie's obvious skill with color surprise you in terms of seeing your work in a different light? You mentioned in one interview that you found his work with textures to be a surprising thing; what do you mean when you talk about texture?

WHITE: I was blown away when Eddie showed me the first few color pages, because he hadn't previously mentioned he was thinking about painting over the black and white art. Similar to the single tier reformat, it was immediately obvious that this was absolutely that right decision. We had, by then, arrived at a single volume approach for the material. Even if people had seen the odd chapters that had appeared in print, the pages were dramatically changed, and so we both consider it a new and original work.

I have always loved Eddie's line work on

the Alec books, where he inks with a brush rather than the flexible nib pen used on

From Hell. He creates magnificently expressive line with a few strokes. I also love the way certain panels contain beautifully observed detail and then disintegrate into almost random peripheral lines. Unlike his fully painted work,

The Playwright was produced in a similar style to the Alec material and then had that added layer of color. I think it displays the strength of his line work and has the bonus the watercolors. These watercolors added richness to the already lively imagery. This added richness, or warmth, is what I meant by texture. The skin tones on the girls aren't merely functional but evoke peaches and cream, and are sexy the way they would be in the Playwright's mind. Uncle Ernie's trousers aren't just gray, they're the one thousand wash gray that are only found on elderly bachelors. The weather in

Cyprus is immediately warmer than that at the English funeral. This artwork is my absolute favorite of Eddie's. But I suppose I would say that.

SPURGEON: I'm catching you fairly late in the publicity process on the book, Daren. What is it like to have a book out these days when there seems to be a staggering amount of material coming from all publishers all the time? Do you worry about not finding an audience? Are you comfortable with these kind of PR efforts?

SPURGEON: I'm catching you fairly late in the publicity process on the book, Daren. What is it like to have a book out these days when there seems to be a staggering amount of material coming from all publishers all the time? Do you worry about not finding an audience? Are you comfortable with these kind of PR efforts?

WHITE: I do worry about the deluge of material and consequently not finding an audience, and to some extent this is accentuated by our distance from our core markets. It's not practical to make more than token appearances within the US and Britain, which does restrict publicity to online efforts. Also, we haven't exactly timed our run well in respect of the global economy. For that reason this type of PR is essential. I'm lucky that, as a relative unknown, working with a creator as established as Eddie will always generate a certain amount publicity. Certainly the rate of reviews we received during the first few months of publication was nice. Chris and

Leigh [Walton] at

Top Shelf were also very supportive of the book and got the word out. The Internet is your best friend when publicizing a book and your biggest competitor at the same time. The market is there but can still seem almost impossible to reach, at times.

SPURGEON: Will English audiences read this work differently, do you think? Whenever you set a work in a specific time and place as you have, the first thing that pops to mind is that there may be a broader satirical point about the setting and era. Did you intend

SPURGEON: Will English audiences read this work differently, do you think? Whenever you set a work in a specific time and place as you have, the first thing that pops to mind is that there may be a broader satirical point about the setting and era. Did you intend The Playwright

to be read as a kind a more general satire, or is it more of a specific character study in your eyes?

WHITE: I think of it as a character study. The exaggeration adds satire but it's meant to be an entertaining look inside the head of an odd man. The awkward, embarrassing humor might resonate more with an English audience but it should be fairly universal. I haven't received any reviews where the reader seems to have missed the point. A British audience might be more familiar with the type of writers I had in mind when establishing his career. Writers like Dennis Potter,

Ken Loach,

Mike Leigh,

Alan Bleasdale and possibly

Jimmy McGovern, who seem happy to work outside of the "big" story themes. One thing that has surprised me is that it seems to have been received similarly between the sexes. I was concerned that it might not appeal to a female readership, particularly when you consider the high ratio of female to male readers amongst books generally. So far the reaction seems equal.

SPURGEON: With both male and female readers having a positive reaction, have you noticed if they have the same kind of reaction, or have they focused on different things about the book? Has anyone's reaction surprised you?

SPURGEON: With both male and female readers having a positive reaction, have you noticed if they have the same kind of reaction, or have they focused on different things about the book? Has anyone's reaction surprised you?

WHITE: I have noticed that female readers seem more likely to be off put by the opening chapters but then enjoy the way it unfolds. I did a radio interview in Melbourne and one of the co-hosts said she almost abandoned the book about a third of the way through. Having stayed with it she really enjoyed the pay off, but initially did question why she was reading it. This has been reasonably typical, which is a touch dangerous for me, as author, because obviously I want, and need, people to complete it. Actually, a few female reviewers have almost justified their enjoyment of the story, given its subject matter. Almost as though they went in expecting to dislike it, and were pleasantly surprised at the way it played out.

SPURGEON: I found myself unexpectedly elated by the ending, and I'm not exactly sure why. At what point during the writing did the ending present itself to you, and was there any temptation that the work take a different turn, perhaps a darker one? Are you surprised at all by the reactions people have had to the work?

SPURGEON: I found myself unexpectedly elated by the ending, and I'm not exactly sure why. At what point during the writing did the ending present itself to you, and was there any temptation that the work take a different turn, perhaps a darker one? Are you surprised at all by the reactions people have had to the work?

WHITE: I'm glad you experienced [it that way] as I do hope that the ending is uplifting. That was always the plan. The end, and the way the second half of the story develops, came to me early in the writing. As I mentioned before, knowing how it would develop gave me freedom to ramp up the sex and black humor during the first half of the book. I was trying to set up the main character in the first half and then explain why he's like he is and explore whether he can change. I also wanted the character development within the story to creep up on the reader. A lot of the changes only become apparent with hindsight. That was always a key element for me, and it's nice when readers get an unexpected reaction.

There wasn't any real temptation to veer away from this. I always wanted the book to be more than just poking fun at the strange man in the corner. I was concerned about the nudity and language, from time to time, but Eddie and Chris Staros both confirmed that it was an essential part of the story. The male nudity was Eddie's idea.

SPURGEON: Daren, you handle the professional side of the Playwright's life with such aplomb, while at the same time the effort of making this book comes from a completely different professional context. One thing that a lot of the interviewees have talked about this year is the state of the market, the shape of the industry. Are the rewards of making comics enough to keep you making them?

WHITE: When I wrote

Batman: Order of Beasts, in 2004, a local newspaper did a short story about it and called me a Chartered Accountant by day who fights crime as a superhero by night. Beyond the joke I made about going to work wearing my underpants on the outside of my suit, that is my commercial reality. I think comics can support a professional writer, however I think publisher variety and speed are fundamental, and currently evade me. You need a constant flow of material, continually reaching publication. Australia doesn't have a comics industry, as such, and so most of my commercial work has come from the US, Britain or Europe. Again, referring to the geographical distance of Australia from those markets, it is very difficult to maintain the level of presence, at conventions and trade shows, to keep yourself in the editors' sights. I can't imagine a time when I won't be working on something comics related. I'm lucky that I can do this work without being wholly financially dependent upon it. I'd love to snag a movie or television deal as much as anyone, however I'm in a position where I didn't have to drop

The Playwright to work on a proposal about wizards and vampire millionaires losing half of their body weight before renovating my garden.

*****

*

The Playwright, Eddie Campbell and Daren White, Top Shelf, hardcover, 160 pages, 9781603090568 (ISBN13), July 2010, $14.95.

*****

* photo provided by White

* the

DeeVee: Molotov annual

* cover to the new book

* three three-panel arrangements, just for the visual feel

* one of the many lovely women Campbell drew for the work

* that red

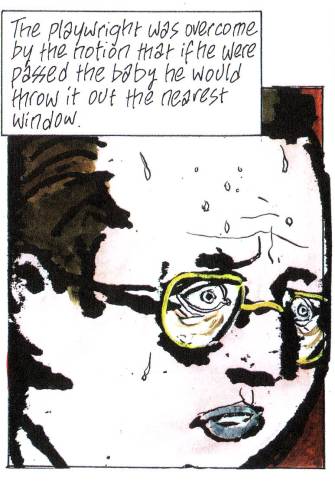

* stand-alone panel I liked

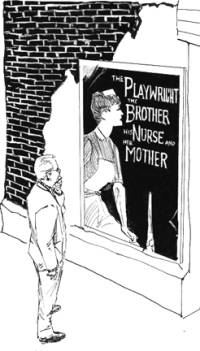

* black and white

The Playwright illustration

* he uses everything

* a subtly, richly-colored panel

* a study from one of the panels as blown up by Campbell

* exaggeration

* one of the sexually suggestive panels

* a blown-up image

* another partial-panel study (below)

*****

*****

*****

posted 12:00 am PST |

Permalink

Daily Blog Archives

November 2019

October 2019

September 2019

August 2019

July 2019

Full Archives