December 25, 2016

CR Holiday Interview #1—Tony Millionaire

CR Holiday Interview #1—Tony Millionaire

*****

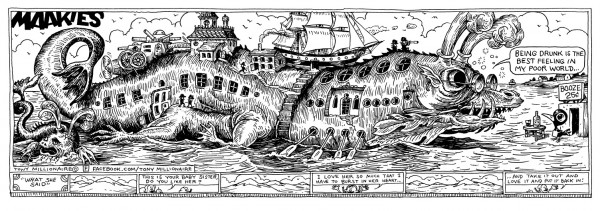

Tony Millionaire ended his remarkable

Maakies alt-weekly strip earlier this month via a wide announcement to press, fans and fellow professionals that accompanied his delivery of the final installment. Never again will we see its like.

Millionaire's lushly drawn, furiously paced, repetitive descents into madness and sometime loss of life were provided to readers for over two decades, during which Uncle Gabby and Drinky Crow became household names, at least in those few houses owned by alt-weekly readers and comics fans.

Maakies was beautiful and ugly and spiritual and profane, usually at the same time. For the bulk of the strip's run, Millionaire essentially did two separate strips in the one-strip space provided him.

Millionaire and I sat down

over lunch and beers in Pasadena after the decision had been made. We met to discuss his strip's retirement, go over some of the highlights and muse on the future. The cartoonist seemed thoughtful and reserved: a tall man, he struggled for a comfortable position in a wooden chair. I always enjoy talking to him. -- Tom Spurgeon

*****

TOM SPURGEON: The first question has to do with your planned announcement that you'll be retiring

TOM SPURGEON: The first question has to do with your planned announcement that you'll be retiring Maakies

, something that if my transcription skills remain unremarkable will be widely known by the time this interview appears.

TONY MILLIONAIRE: I am making that announcement right now.

Maakies is dead.

SPURGEON: Wow.

[a nearby jukebox suddenly to life playing a happy pop tune, causing everyone at the table to laugh; we ask for it to be turned down]

MILLIONAIRE: Maakies ran from 1994 -- February 1994 -- to now. Which is like 22 years, almost? Or 23. I don't know, my math is not good. At its peak it was in twenty-something papers: the weeklies. The

LA Weekly, the

Village Voice. All across the country.

SPURGEON: What was the first paper? I should know this, but I'm drawing a blank.

MILLIONAIRE: New York Press.

SPURGEON: Your "flagships" would have been, I guess, that one and maybe LA Weekly?

MILLIONAIRE: LA Weekly I got when I moved to LA and I ran into

Carol Lay and she said, "We'll get you into the

LA Weekly." She made some calls and I was there.

This was good because a paper of that size would pay a decent amount of money. Some of the papers would pay ten dollars. In fact, there was one I was doing I was doing for one dollar, because I had to charge them something or

Kaz would have ripped my head off. Kaz thought I was undercutting his prices and in doing so undercutting his profits. So it was kind of a joke, but not really.

SPURGEON: I wasn't aware of any of this.

MILLIONAIRE: He wrote me a song called "Tony Penny." I forget how the song went but the title was "Tony Penny." [reflective pause] "Doesn't have any."

SPURGEON: [laughs]

MILLIONAIRE: I just wanted people to see the strip at that point. That's the problem with it now, nobody sees it. I'm not dedicated enough to upload it every week on time, to get a following on the web site. I just drop it on Facebook every now and then when I have one done. I'll get a bunch of comments, but it's just not fresh anymore.

The other problem is that some of the jokes are very offensive now and for a long time they weren't that offensive.

SPURGEON: From where to you get criticism? Based on what? The violence? When people complain, what do they complain about?

SPURGEON: From where to you get criticism? Based on what? The violence? When people complain, what do they complain about?

MILLIONAIRE: They complain about jokes about women's menstrual cycles. You start making jokes like that... The joke that got me kicked out of Baltimore was one about there's a lawyer in a court and he represents a woman. The judge asks what's the grounds of this divorce? The lawyer says she is filing for divorce because she's on the rag. That got me kicked out of Baltimore.

SPURGEON: I know from strip people in general that many of them feel that there is less support in general from papers and the people that work there for the strips they run. Did you come to feel that way?

MILLIONAIRE: Yes. [pause] It depends on the paper. The

Austin Chronicle, I've been in there for years, they're the last one. They're very supportive. It's Austin. But I found that some of the older papers and older editors before they moved along and the younger editors took over. I found the older editors understood the cartoonists as a newspaper men, getting that store in there... What was that

Joe Pesci movie?

SPURGEON: The one about Weegee?

MILLIONAIRE: Him. Getting into fights over the photographs. He invented the shoe on the pile of rubble. Throw it down there. [laughter] I'm not sure that's true.

SPURGEON: When we first heard about you out in Seattle, we heard about you

just as much as the strip. It was reminiscent of the personality-driven era of great newspapers. "You gotta see this strip, the guy who does saves it until the last day." [Millionaire laughs] I don't know today how much of that was true. Still, there was an element of participating in the strip with you, to see if you could keep it together and get it out. Was that on purpose?

MILLIONAIRE: I was famous for being a personality, at parties. "It's Tony Millionaire! He's a riddle wrapped in an enigma! He's got a bottle of vodka in the front pocket and god knows where the teeth are!" [laughter]

I'd take my teeth out when the fights started. I was the tallest, drunkest person at all of the parties. It was fun.

SPURGEON: The tension of your persona was that while you were this crazy personality, the strip was very disciplined. You didn't have problems getting work out, like an Al Columbia or, I don't know, a David Choe, where the outsized life got in the way of at least some production. You were there every week.

MILLIONAIRE: The deadline was very important to me.

SPURGEON: There's an element of sheer fortitude in getting work out like in regular fashion for that many years. If your strip was horrible, there'd be a certain amount of respect in hitting that many deadlines. But your work is extremely well-crafted, and frequently beautiful.

SPURGEON: There's an element of sheer fortitude in getting work out like in regular fashion for that many years. If your strip was horrible, there'd be a certain amount of respect in hitting that many deadlines. But your work is extremely well-crafted, and frequently beautiful.

How does having something like that as a centerpiece of your life feel? Where does that strength to keep getting it out come from, do you think? Is that how you approach most things?

MILLIONAIRE: No.

SPURGEON: It was special to the strip, then?

MILLIONAIRE: It was special. The

Maakies strip was the one anchor in my life. It was a place I could spill my guts. It was a thing that I had to do. I didn't even know where I was going to live next -- I didn't start it until I was 40. My life was very aimless. What city I was going to be in, where I was going to get my spaghetti and mashed potatoes.

Then I started doing a strip. I started doing one for a very small newspaper in Brooklyn: the

Waterfront Week. Every week that strip had to be in. That's the one thing I had to do. Everyone else had to get up and go to work in the morning or quit their job. But the one thing I had to do was I had to have that strip. That's where discipline came from suddenly for the first time in my life. When it started appearing in newspapers, I was like, "I need this." I don't have anything else.

From that strip, all my other work came. People know that I can draw, and that my drawings have personality and are funny, from that strip.

SPURGEON: That's an underrated element, the calling-card element. There's no doubt you can come through on a project.

MILLIONAIRE: It shows you're going to get the job done and it will look good.

SPURGEON: Can we put an hourly figure on an individual strip?

MILLIONAIRE: It would basically take an entire day. Sometimes that was four hours, sometimes that was ten. The first panel took longer than all the other panels. I'd research, try to find reference for a ship or a bar, and then make it more compact. Then I'd start drawing, and I'd know what the strip was going to be. Sometimes getting the joke would take all week.

SPURGEON: Was there a rewrite process involved, internally? For that matter, what about externally?

MILLIONAIRE: No. I got one note back from an editor that I think went to a few of us. "Guys, this isn't Playboy Magazine." [Spurgeon laughs] "This isn't

Hustler. Knock it off."

SPURGEON: The relationship between the characters, the end results, there's a refined language to your approach. Like the most famous single image from your work is a recurring image in your narratives: Drinky Crow offing himself.

MILLIONAIRE: Drinky Crow. The great bird.

[Tony raises his glass and there's a toast to Drinky Crow.]

SPURGEON: When you have these elements, these expected behaviors... you might riff on it, but even then there's a feeling that you're pushing back against expected norms. How over that many years did you find ways to keep the material rich, without repeating yourself? Did you ever feel constrained? Was the strip ever particularly difficult to write?

SPURGEON: When you have these elements, these expected behaviors... you might riff on it, but even then there's a feeling that you're pushing back against expected norms. How over that many years did you find ways to keep the material rich, without repeating yourself? Did you ever feel constrained? Was the strip ever particularly difficult to write?

MILLIONAIRE: There were times I had no idea what to do, where it'd be two o'clock in the morning and I knew I had to get something done. There were a couple of tricks I would use.

Most of the time there was a joke already written. Somebody had said something funny. Like my friend Helena Harvilicz. I was doing a Nicholas Cage impression from

Leaving Las Vegas. And I said, "Just one thing, honey. Promise me you'll never ask me to stop drinking." And she said, "Can I ask you to stop peeing on my leg?" [laughter]

All the jokes came from things that happened to me when I was out doing something, but sometimes you wouldn't have anything for weeks and months at a time. That's when I would look at old books of my comics, sort of find an idea and maybe sort of rewrite that. Or be inspired to move something in another direction.

It's like the movie

Blue Velvet. They find the ear in the field -- SPOILER! [laughter] -- they find the ear in the beginning of the movie. They get closer and closer to this ear and then they go inside the ear and I'm thinking, "This is going to be

great! What is this?" And then it's just a candle in the wind. I guess it was okay. But what did I think it was going to be? Then I did a comic about that.

SPURGEON: The late period of your work with Maakies

-- as things started to implode a bit, industry-wise... I always get a sense from you that you were aware of the precarious position you were in. Because, really, the last half of Maakies' existence was a tough time for the industry in which your work was placed. How did you negotiate that increasingly slippery ground?

MILLIONAIRE: You mean the collapse of papers, the notion there was less space for comics.

SPURGEON: All of it. You stuck it out while other cartoonists reconfigured their careers. You were right on board the strip during

the viking funeral: flames all around you, dodging incoming arrows.

MILLIONAIRE: [laughs]

SPURGEON: Did that add a level of stress to the comics-making, something that we might only see years from now?

MILLIONAIRE: It added a certain amount of stress. Newspapers were going because of the Internet. People used newspapers to find out what was going on, and now they go on the Internet to do that. I knew it wasn't going to last. I thought that to myself that it was the last days of doing this kind of thing.

But I only had to do it once a week. I had the rest of the week to figure out what I was going to do. I was doing a lot of illustration work, now I've done a lot of record covers for famous people. Stuff like that. But I also knew that I had to figure out a way to get it online. It was still the beginnings of on-line. You'd set up a web site and then you hoped people would go to it. You'd mention it in the strip to build a following, but you couldn't make any money doing it. I never did. At best I made $300, $500 a week, when it was in a lot of papers. But it was my calling card, and a lot of people could see it.

Then Facebook came along, and Facebook started turning more and more into imagery, and now most of my interactions are on Facebook. Past strips and other strips.

SPURGEON: The old-fashioned way that strip cartoonists used to describe doing a feature is that you'd tell your jokes onstage at an empty theater and then a couple of months later you'd check box office receipts to see how they did.

MILLIONAIRE: [laughs]

SPURGEON: Does the feedback received change the creative process?

MILLIONAIRE: Yeah.

SPURGEON: How so? Do you lean into what people like? Is it just enjoyable to get feedback, the pleasure of a live audience.

MILLIONAIRE: Feedback is very important. You want to test out a joke. I show it to my wife, and to my kids. Sometimes I'll try out the joke before I draw it and people are like "I don't know" and I say, "I'll make it work."

When it gets in the paper, especially in the beginnings from the

NY Press, I'd get letters. All the cartoonists with strips in the

Press got letters. Kaz was in there. Carol Lay was in there.

Steven... what was his name? I love that guy.

SPURGEON: That's kind of the fate of Steven

.

MILLIONAIRE: I felt like I was this raucous drunken character, stepping on his toes. Mark Newgarden and Mark Beyer were in there. So you'd get letters, and there was the

Comics Journal Messageboard, and everyone would battle it out on there.

Doug Allen was

Steven. He was there long before I was.

SPURGEON: Steven

gets no credit now and it was a great strip. Brock, the Cactus... Did you feel a kinship with your fellow alt-weekly cartoonists? Did you ever feel a part of the crowd, either in the alt-weeklies or later on with the books at Fantagraphics?

MILLIONAIRE: Oh yeah. Of course. There was a real community. We all knew each other.

The cartoonists talked to each other and the editors didn't, really. When the

Village Voice fired Jules Feiffer, he had an editorial position. They wanted to fire him but buy his strip from his company. And Feiffer was like, "No. You're not getting the strip if you fire me as an editor."

The editor of the

Village Voice started calling around, saying "Anyone want to jump ship? Anyone want to come over here and publish?" The cartoonists would call each other and would be like, "Did you get a call from the

Village Voice?"

When they finally called me, I remember I was lying on the couch. "Oh, you want to run my strip in the Village Voice?" He said, "Yeah; do you want to jump ship?" I said, "That sounds great!" "Does it sound a great?" And I wish I could remember the wording of this... "I'm definitely interested." He goes, "You are? That's great." I say, "Yes, I'm definitely interested in you going to fuck yourselves." [Spurgeon laughs]

They wanted to offer me 400 bucks for that, and I was only getting $60. We were loyal to one another. The only one who wasn't will go unnamed. We gotta help each other out.

SPURGEON: So what takes Maakies

' place? Does the on-line Adult Swim cartoon step into that role?

MILLIONAIRE: That's a new thing. That's only been about three or four months. I don't know how long that will go.

SPURGEON: Is there a plan moving forward or is it just kind of taking the opportunities that are coming to you?

MILLIONAIRE: I don't need

Maakies anymore in that I'm always getting contacted for work. There are projects I start up myself. Two books right now. People call me up and ask, "How do you get into the business?" and I have no idea. I did it my way. I walked backwards into a party and there was a guy from the

New York Press there and I was funny. "We gotta get this guy a comic strip." Do that! [laughter]

SPURGEON: Are you looking forward to that relative freedom, being freed from that very specific thing you have to do every week?

SPURGEON: Are you looking forward to that relative freedom, being freed from that very specific thing you have to do every week?

MILLIONAIRE: No, I'm not looking forward to it. I'm really going to miss it. On the other hand, I'm too busy to miss it very much. One of the books I'm working on is

Tony's True Tales -- that's the working title, I don't know what I'll call it. That's true stories from my life. There are a lot of them. I lived in Europe. I'm going to put Drinky Crow and Uncle Gabby into those comics as my pals. It's not that Drinky Crow is dead, it's that the

Maakies strip is gone.

Since you asked, if someone wanted me to bring

Maakies back to life where 500,000 people would look at it every week, I'd do it. That's the problem, no one sees it anymore.

SPURGEON: The all-ages stuff, is that part of the landscape moving forward?

MILLIONAIRE: That's one thing. Whenever I try to do children's stuff my creepy dark side come out anyway, and it ends up... well, that's not fair, because kids love creepy dark stuff. It's not like I put scatological stuff -- you can put poopy in, what am I talking about? -- but I don't put sex and certain things you don't want to talk to kids about.

I'm working on

Billy Hazelnuts, the last of the trilogy. That's almost done. That's kind of aimed at kids but not necessarily.

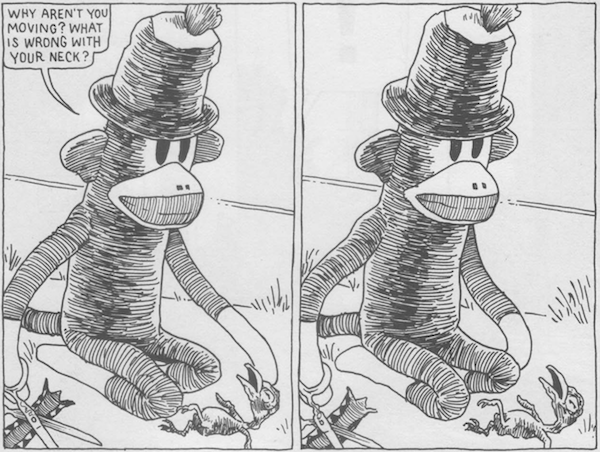

The Sock Monkey is actually not really aimed at kids, it's aimed at people who remember kids books. Who remember the nostalgia that you feel for when you had a stuffed animal that was your friend. My daughter is 15 and she picked up the

Sock Monkey book the other day. She's like, "These stories are really good. I never realized." I was trying to show them to her when she was ten and she was like, "I don't know, Daddy... It's not that good" Now she realizes those are real stories.

SPURGEON: That's a real gem of a book. It was vastly under-appreciated when it came out, and remains so.

MILLIONAIRE: I love that book. It won a couple of awards. The bigwigs that give out prizes appreciated it.

SPURGEON: The suicide attempt in Sock Monkey is still one of the great scenes.

SPURGEON: The suicide attempt in Sock Monkey is still one of the great scenes.

MILLIONAIRE: That's a good one. That one gets to you every time you read it. He accidentally kills the baby bird. Every time I read that, I still get goosebumps.

SPURGEON: It's an incredibly strong sequence.

MILLIONAIRE: If the author can read it and still get goosebumps again, that's good stuff.

With

Billy Hazelnuts, I have to wrap it up, I need to put a real goosebumps moment in it so people remember it.

SPURGEON: Your life has changed tremendously since you started Maakies

. You live in a different place, you have a family. Did the strip reflect those changes, your outlook at any particular moment. Was there any period that made doing the strips more difficult?

MILLIONAIRE: The strip has always been pretty much a diary of my life. Not exactly, of course. But you can find out what I was thinking, how I was feelilng, but reading the collections. If you know me. So that never really affected it negatively. I would change. I don't have Drinky Crow blowing his brains out as much — well, now I do. [Spurgeon laughs] But for a long while, it barely happened at all. I just didn't feel like that.

When it first started, I sure did. [Spurgeon laughs] I didn't feel like killing myself, but I saw getting drunk as temporary suicide. You do it when life sucks. When Trump happened, everyone I know grabbed a bottle and hugged it for three days. I handed in a re-run that week.

SPURGEON: Are there influences you see in your work that you wonder if anyone else gets?

MILLIONAIRE: Uh-huh. Sure there are.

SPURGEON: Who might that be?

MILLIONAIRE: Mark Twain. Herman Melville -- not just because of the strips, but because of the way he writes. Melville was very funny. You read Moby Dick and you realize it's a comedy; there's a lot very funny stuff in it.

I've never read a lot of comics, so when people ask me about my favorite cartoonists I have to rack my brain... Kate Beaton. Who is

Hyperbole and a Half...? Allie?

SPURGEON: Allie Brosh.

MILLIONAIRE: I just don't read a lot of cartoonists. I don't remember them by name. My reading for pleasure is classic, mostly comedy books: work by Jane Austen. Mark Twain.

The Patrick O'Brian series I've read them like three times. That's a look at a life at sea in the early 1800s. On a navy ship. It's so well-written. It's funny, and it's done in the comedy of the time. It's not the comedy we're used to right now.

SPURGEON: What is it about that kind of comedy that's specifically appealing to you?

MILLIONAIRE: I get tired of a lot of comedy nowadays. It's all so predictable we're used to it. "Ba-dump-bum-bum." and then "Ba dump bum boom." It's almost like a second language when you read stuff that was written in the 1800s or the 1700s. Like Washington Irving. The style is different. Values were different then. You really could end up in a duel for slighting somebody. The sense of duty was different.

The comedy in those days... all we really had was words. We didn't have recorded music, or television. We had books. All the people who would have been making amazing movies nowadays -- and there are a few -- were writing books then. Poetry. Lord Byron. Think of the greatest comedian you know, the person writing the funniest television, the best cartoon, they would have been named Mark Twain and they would have been writing books.

Roughing It.

The Innocents Abroad.

So my influences come from actual books. I read all the really old newspaper comics. But I never read comic books.

SPURGEON: I think you'll also1 be remembered for the strip at the bottom of the strips — that's a signifier for you in the way that the silent third panel will be something we remember about Doonesbury

.

MILLIONAIRE: That's a callback, too, of course, to the old newspaper strip.

SPURGEON: Sure, the Sundays that ran a second feature.

MILLIONAIRE: Ma Green was at the bottom of

Little Orphan Annie.

The Family Upstairs had one called

Krazy Kat that became

Krazy Kat.

SPURGEON: Segar had his inventor... Was that creatively useful? It felt like those bottom-strip jokes might have come easier than a primary strip joke. I figured it might have been useful to have that joke there over the long-term to help you create.

MILLIONAIRE: Very much so . They came from a specific incident. I had a bartender in Brooklyn that wasn't very bright. My comic strips were more poetic than anything else. She said, "Tony, I don't get your comics. I really just don't get them." And I was like "A-ha, I'll do a second one just for you... why did the chicken cross the road?" Something like that. There was some joke to it and she laughed. She said, "Do that for me every week, would you?" I said, "I will." And so I do!

The top joke I can be poetic and use all the visuals to make a story. It can be complicated. I'd prefer it to be funny, but it doesn't have to be. The bottom one is a joke: "Please can I ask you to stop peeing on my leg?"

Kaz would say to me, "What are you doing? You're not getting paid to do two jokes. You're giving them two jokes." [laughter]

SPURGEON: How has the extra work changed the way you do the core cartoon? Jaime Hernandez has spoken of coming close to resenting the other work he does because it keeps him from his comics. How do you look at these other opportunities?

SPURGEON: How has the extra work changed the way you do the core cartoon? Jaime Hernandez has spoken of coming close to resenting the other work he does because it keeps him from his comics. How do you look at these other opportunities?

MILLIONAIRE: It improved my drawing. That's about it. On Tuesday night, it's

Maakies time. Well it used to be. It won't be anymore [collapse on tables, fake crying] [laughter]. Oh, God!

Tuesday night I wasn't going to anything. Not to a birthday party. Not to your fucking wedding. I have to concentrate on the strip or I'll be up at 8 AM the next morning. Anything outside that might influence me I'm not thinking of it.

SPURGEON: Your early work there are some different elements, different things you emphasize, but it's recognizable as yours. There's no great shift the way you've seen with other cartoonists. You've been consistent. You were right there at the beginning. How much have you worked on elements of the strip, or did the strip itself necessitate the skills to get it out.

MILLIONAIRE: The work necessitated the skills. Every now and then I'll be like "It'd be nice to make road rounding a corner with a cliff over there and a crumbling wall, drawn in an old-fashioned style." I don't think, "I can't do that." I would just do it. I have all these references, and I'd either use that or my head to just figure that out. It's just something you learn.

From since I was in college until I was 40, I drew houses for a living. Every house I'd been hired to draw, I had to figure if it was a straight-ahead portrait, or a three-quarters, where a tree might be in a way. Those were cold drawings -- I didn't use a ruler, so they weren't that cold. I found the funnest part was usually the bushes and trees around the house. You had to draw the stems and the leaves and decide if you were drawing from a flat plane. If the yard looks like it starts here and goes back... I'd study these Van Gogh sketches of these farms. He'd draw grass in front of it, then smaller grass, and eventually just straight lines.

[food arrives, much praising of the food and small talk about the Christmas season at the Millionaire household]

SPURGEON: So what happens to the strip now in terms of archiving, caretaking? You have a new format with this latest book Jacob Covey designed. Are you going to do the old strips again? Have you given any thought to its continual archiving.

SPURGEON: So what happens to the strip now in terms of archiving, caretaking? You have a new format with this latest book Jacob Covey designed. Are you going to do the old strips again? Have you given any thought to its continual archiving.

MILLIONAIRE: You could do the whole run. Twenty-two years of

Maakies.

SPURGEON: That would be an incredible book.

MILLIONAIRE: It would be. It would be a lot of paper.

SPURGEON: Do different people read the books than read the strip?

MILLIONAIRE: I don't know who was reading what. I really don't. People will make comments that they're reading, you don't know what. When we got

The Drinky Crow Show, I thought it would boost the sales of the book. But it didn't. I found out later that people that watched the show didn't know the books existed. People that read the book didn't know the show existed. Generally.

SPURGEON: It's not the worst place to be, though, I guess in terms of people just not knowing things.

MILLIONAIRE: I find that ignorance applies to a lot of things. I bet a lot of kids don't know the Batman comic books exist, or at least they've never seen one.

SPURGEON: A lot of adults are amazed that stuff is still published. It's like finding out we're still making The Shadow

radio plays.

MILLIONAIRE: There are some people that do well. Dan Clowes sold a lot of

Ghost World books. Dark Horse came into the picture from a merchandising end, noting that Fantagraphics didn't really do merchandising. They did t-shirts and plastic toys and party lights.

SPURGEON: You like that stuff?

MILLIONAIRE: If I have control of it, yeah. I would send over these sketches of Sock Monkey to the Chinese manufacturer, and they were confused by what was on his head, so the first prototypes came back with him wearing a rose on his head. I'm like, "No, that's a pom-pom." And they're like, "a prostitute?" Because that's what the word means in Chinese. Then they did another kind of flower, like a clover. I'm like, "Not that, either." I went to the thrift store and found a stuffed toy with a pom-pom and I mailed it to them. [laughter]

SPURGEON: Are you good at the business part of it, the managing of your career? Are you good at finding the best public opportunities for your work?

MILLIONAIRE: I'm not that good at it. I mean, I try to publicize the books as much as I can. Some people make a lot of money to do this, but I don't.

SPURGEON: Would you like to be better at that?

MILLIONAIRE: Yeah! I'd like to have some more money. I'd like a lot more money. [laughter]

SPURGEON: Who is someone you think does that well?

MILLIONAIRE: Coop. Coop used to do it better with his previous wife, who seemed a real master with that. I said, "Jeez, I see that devil with the cigar everywhere." He's like, "Yeah, that bought me a jaguar." I'm like, "You mean a Ford?" [laughter] That's like a $60,000 car.

Just last week they were going to send me a quarterly check that was two cents or two dollars, from Dark Horse. I realized that the plastic crow sold like $95,000 over the years. People bought it after the show because they saw it. I don't know how that shit works. I just want a bunch of money. One million is the same as two million to me. No million dollars, that doesn't work at all. That's way different than two million dollars.

SPURGEON: You've been honest about that aspect of cartooning over the years, your ability to provide. Do you consider those things when you make a change like this one?

MILLIONAIRE: You mean having no

Maakies.

SPURGEON: Yeah.

MILLIONAIRE: No, I think

Maakies got me to a certain level of fame, and now I have a day to work on the stuff that pays better. There are so many places to provide material, certainly something will happen sooner or later. I've been on the verge of wealth for year. The ship gets right to the edge and then does not fall. I've been so close so many times.

SPURGEON: When did you feel the closest?

MILLIONAIRE: SNL. That was in '98. "I'm on

Saturday Night Live! I'm on TV." I was imagining the house. "This is going to be great." Then... nothing. [laughter] They made six little cartoons and only showed two. Tim Maloney picked them up for DVD with some other cartoonists: Brunetti, Henderson. I also sold it to Spike and Mike. Ike and Spike and Mike. Spike and Ike. I used to rent it out to them for ten years.

A good friend of mine, a writer Todd Alcott, we're working on a new

Sock Monkey TV show. As soon as I finish up

Billy Hazelnuts we'll take that around and see what happens.

With the movies, I think every studio has been approached three times each with

Sock Monkey. "This is fantastic! This is great!" They'll watch the video and hold the sock monkey when they watch it. "We're talking lifetime annuities." Ding! Ding! Ding! Booinng! My eyes are dollar bill signs. "I see it, too!" Two weeks later: "Oh yeah, man. They shot it down."

That's their job, to make you feel fantastic.

SPURGEON: Any chance you'll act more?

MILLIONAIRE: [laughs] My problem is I can't remember lines. I was a gay dude in something. I'm talking to my boyfriend, and I'm supposed to say, "C'mon, we're supposed to go the Dunkirk meeting." I just read that off that sign [pointing], because I don't remember now. But it was one line, I barely got it out. When you see it, it's like "Who's this guy? He's not even acting."

When it comes to acting like a fucking goofball, that I can do.

SPURGEON: So twenty-two years. Tony, do you feel appreciated?

MILLIONAIRE: Oh, yeah. You want to know how appreciated I am? Go to Google Images and type in "Drinky Crow Tattoo." It's like five pages of tattoos. I don't like tattoos. I would never get one. But some of them are beautiful. When you see your art painted on somebody's body that many times, you know you've done something all right.

*****

*

Tony Millionaire

*

Maakies: Drinky Crow Drinks Again, Tony Millionaire, Fantagraphics, hardcover, 128 pages, 9781606999349, July 2016, $29.99.

*****

* Tony Millionaire, at our interview; photo by Whit Spurgeon

* the last

Maakies

* the on the rag

Maakies

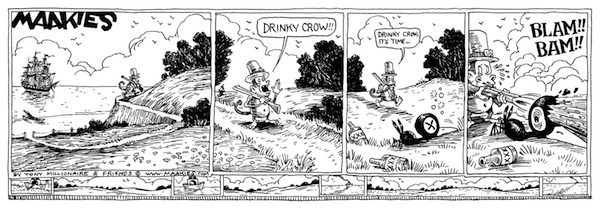

* the first strip

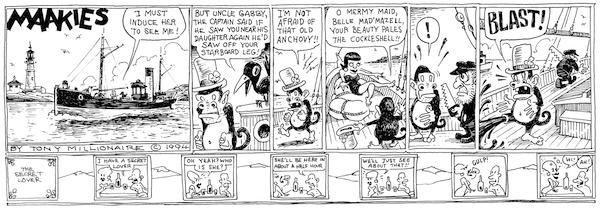

* a favorite strip

* Elvis Costello album cover

* from a Billy Hazelnuts story

* from that suicide story featuring Sock Monkey

* a Moby Dick Illustration

* the cover to the latest collection, with art director Jacob Covey

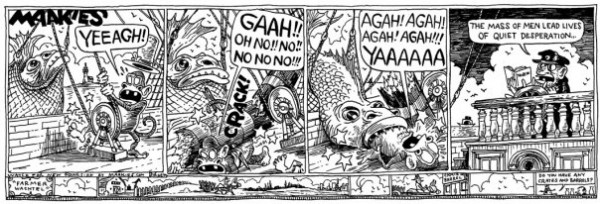

* a favorite Maakies (below)

*****

*****

*****

posted 5:00 pm PST |

Permalink

Daily Blog Archives

November 2019

October 2019

September 2019

August 2019

July 2019

Full Archives