December 21, 2010

CR Holiday Interview #2—Karl Stevens

CR Holiday Interview #2—Karl Stevens

*****

Karl Stevens fascinates me because I'm not exactly sure why his obviously accomplished work isn't yet received with greater fanfare. That's not to say he lacks an audience now: his work has been successfully serialized by the

Boston Phoenix, and his ongoing feature

Failure won an AAN award last summer. All of the books he's released to the comics market received a fair share of praise, too. Stevens' latest offering,

The Lodger features the autobiographically-driven, realistically-rendered, quick-in and quick-out strips that are nearly his exclusive purview in this comics era. Dramatic shifts in living arrangements, romantic entanglements and an increased ambition for his art provide the book with a great deal of energy from the first page onwards. Stevens sees his more standard visual arts practices and comics as part of a single visual continuum, something he discussed below. What makes this approach fun as comics is that you get to see those pages as work product, visual narratives themselves like the ones before and after them, or as a way to track what's on the author's mind that breaks with other parts of the story being told. The material blends so smoothly you almost feel bad making a point of it at all. The following discussion took place in almost scatter-shot fashion over the last couple of months and was tweaked very slightly for flow. My greatest hope is that a few more people will look into Stevens' work as a result. -- Tom Spurgeon

*****

TOM SPURGEON: Karl, I'm pretty sure that most CR

readers don't know the history behind the serialization, and where this fits in with past projects. Can you unpack that as deliberately as possible? This was a new serial to replace an old serial, am I right? Is it still ongoing?

KARL STEVENS:

Failure is an ongoing weekly comic for the Boston Phoenix that deals with autobiographical and humorous slice-of-life narratives and can be viewed every week on the phx.com website for non-Boston area readers. It started in January 2009 as the replacement for my previous comic feature called

Succe$$, which was a fictional account of four eco-financiers and was co-written with the writer/critic

Gustavo Turner. That strip only lasted 35 installments because of my desire to return to a more personal way of expressing myself, more in the vein of

Whatever, my first weekly feature for the paper (the three-year run of which was collected in 2008 by Alternative Comics).

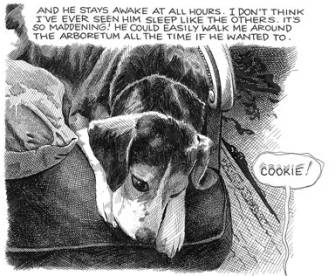

Whatever, though, focused on fictional characters, whereas

Failure is based more in autobiographical anecdotes and observations. It has been very rewarding artistically over the past two years and the strip even won the AAN award this year for Best Cartoon!

SPURGEON: Can you talk a bit about that choice to move away from autobiographically-informed work in more of a straight autobiographical approach? What made you think that this was the way to go? Has anything about that approach surprised you?

SPURGEON: Can you talk a bit about that choice to move away from autobiographically-informed work in more of a straight autobiographical approach? What made you think that this was the way to go? Has anything about that approach surprised you?

STEVENS: My choice to move away from the autobiographically-informed work into the more straight auto-bio work was simply a matter of curiosity. I always wanted to try my hand at it, being a big admirer of the work of

Julie Doucet,

David Chelsea, and

Eddie Campbell. It seemed like a natural progression with the weekly deadline for the

Phoenix, too, a lazy way to stay afloat -- "If all else fails, I can just write about how stoned I got last week." Also, using myself as a model was ideal; I'm usually pretty available. But seriously, I thought it would be interesting to use my friends' real names and try to imbue them with my impressions of their personalities. Which is something that I quickly found out to be problematic. "What the fuck, I would never say anything like that!" is something I heard a lot. [Spurgeon laughs] I shouldn't have been surprised by that.

SPURGEON: Is there a scene of individual installment that you think works better for being done this way instead of through fiction?

STEVENS: I don't really think there's a particular scene in the book that works better through this approach. The way I conceived it was as a narrative, and I used various methods and tropes of fiction to tell the story. It still reads as fiction to me in a sense, since the characters' lines are being written by me. That may be my friend Jamie O'Brien drawn there on the page and he may have said something similar to what's in that word balloon, but ultimately it's me that's pulling the strings. Though, I say all this as I'm now currently moving away from auto-bio and back to longer fiction.

SPURGEON: This is I think a third or fourth book for you -- are you a devoted self-publisher, or would you prefer to work with an established publisher if that were an option? What do you enjoy about that hands-on approach? Is there anything you dislike?

SPURGEON: This is I think a third or fourth book for you -- are you a devoted self-publisher, or would you prefer to work with an established publisher if that were an option? What do you enjoy about that hands-on approach? Is there anything you dislike?

STEVENS: This is my third book and second that I've self-published. My first book

Guilty was self-published through the assistance of a

Xeric Foundation grant, and the follow up,

Whatever, a collection of my early weekly strips for the Phoenix, was published by Alternative Comics. I do enjoy the hands-on aspects of self-publishing, and being able to have the books in stock for talks and conventions and what not. That said, I would be open to have future books being published by an established publisher.

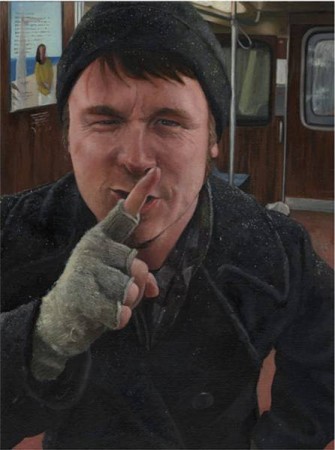

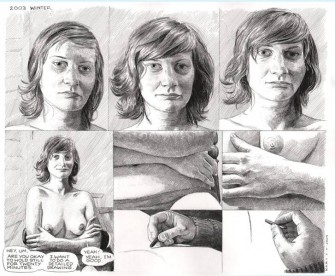

SPURGEON: One of the more striking aspects of the work is that you fold in portraiture and other expressions of your art right there into the flow of your more standard cartoons. Was that something you were able to approximate/accomplish in the serial or is that just something that occurred to you as you assembled this book? Did you make any of those pieces of art or even all of them with where they fit into the narrative, or did any exist independently of this project?

SPURGEON: One of the more striking aspects of the work is that you fold in portraiture and other expressions of your art right there into the flow of your more standard cartoons. Was that something you were able to approximate/accomplish in the serial or is that just something that occurred to you as you assembled this book? Did you make any of those pieces of art or even all of them with where they fit into the narrative, or did any exist independently of this project?

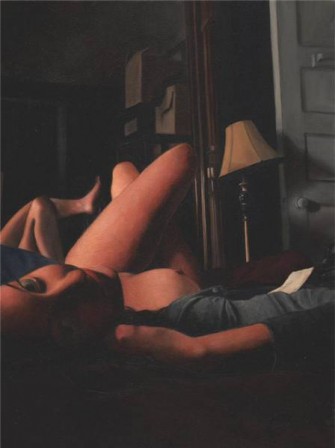

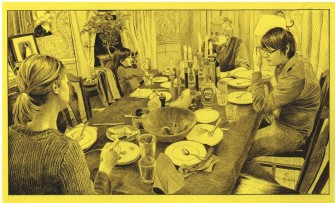

STEVENS: The other aspects of the work -- the oil paintings, watercolors, and graphite drawings -- were worked in more or less around the same time that the traditional comics were being produced for the newspaper. The book was conceived as a year-long project from the beginning. I had a general idea for how I wanted the narrative to be played out, and I was interested in approaching it in a way that combined my other visual art inclinations. I've always been interested in how forms of representational art are connected to each other. I don't believe there is much difference between what can be expressed in the different mediums. For me Michelangelo is working in the same visual language as Charles Schulz: the only difference is content and style, but both create powerful and personal worlds. This to me is the core of what I want to achieve as an artist.

SPURGEON: I want to follow up on both part of that answer, latter part first. What do you mean by creating powerful and personal worlds? Where do we see that in your work? Where and how do you think that element of your work finds its best expression in The Lodger

.

STEVENS: By creating powerful and personal worlds, I mean taking a conception and extracting, it in a way that best suits it, through style. This is something that I believe is developed over a long period of time by working within a certain number of self-imposed stylistic limitations that allow the artist to grow into him or herself. In turn, the artist develops a "personal world" that can be traced throughout each different work. In Michelangelo, you can see it in the difference between the Sistine Chapel and the Last Judgment, in the development of the way that he executes anatomy and space: the latter work is more exaggerated, but it's still clearly Michelangelo. It's the same thing with Schulz; the limitations of the four-panel comic and the simple drawing style enabled him to concentrate on developing the conception of what the whole of the work was. It freed his thinking to allow the work to do the talking.

In my own work, with

The Lodger, I find myself trying to bridge my forms of other art-making together -- meaning, specifically, incorporating the paintings into the book. I spent years thinking that I was both a cartoonist and a painter and that those worlds were separate entities. Lately I have realized that I am neither: I am an artist who uses both mediums to create a story.

The Lodger is my first book to explore this direction.

SPURGEON: That seems like a pretty heady discovery to make in the process of working on a book. Do you think the work might be different if you had had a firmer grasp on working with multiple approaches to the same end? Is there anything, perhaps early on in the work, that you think shows how far you've come since?

STEVENS: No, looking back on it, I feel I kept the pacing pretty consistent and that forced me to approach the story in a certain way. I think the way the early pages differ from the later ones is very small, maybe a slight shift technically in the way I was using more brush with the pen. Loosening up the line work a little.

SPURGEON: When you say you had a general

idea of how you wanted the narrative to be played out -- how much of that were you able to execute? Because it seems when you enter into a new relationship your book changes direction suddenly. Was that kind of personal development included in your conception of how you wanted the book to play out?

STEVENS: When I say general, I mean I knew that it would be a year-long chronicle of what I chose to reveal about my life. Of course I couldn't plan on meeting and dating Anne during that time, that would be sociopathic! The book was an experiment in narrative; I wanted to see how the growth of a character could be depicted though the chronicle of a year. I could've easily have descended deeper into alcoholism or even developed a harder drug habit. Or maybe have joined the marines--okay, maybe not that.

SPURGEON: I thought this book was funnier than my memory of your past work, or at least more expansively funny. Can you talk a bit about what you find funny, how you deal with humor in the kind of work that you do? For one thing, I imagine there's an expectation that a strip in an alt-weekly will be funny.

SPURGEON: I thought this book was funnier than my memory of your past work, or at least more expansively funny. Can you talk a bit about what you find funny, how you deal with humor in the kind of work that you do? For one thing, I imagine there's an expectation that a strip in an alt-weekly will be funny.

STEVENS: Thanks, I think it's funnier too. Humor is something that I've always been attracted to, and actually prefer in art. I was raised on the Mad magazine of the 80's and early 90's, and would scour the back issue bins at my local comic shop looking for old ones from the earlier decades. I learned how to draw with pen and ink through studying those things, staring at the line work of

Drucker,

Woodbridge,

Martin,

Wood, and

Torres. I spent a lot time time copying them, and making my own little minis that were complete rip-offs. This work formed me and in turn led me to the work of

Dave Sim,

Peter Bagge, Eddie Campbell, and

R. Crumb. Their work and the

MAD stuff are the core of where I wanted to go as a cartoonist. Even later when I started painting and became a student of art history, their influence was still present in how I wanted to proceed as an artist.

As far as the weekly strip goes, there isn't an expectation that

Failure be funny every week. I just kind of like it that way, especially since the art is so naturalistic. I like the juxtaposition of the two.

SPURGEON: Do you think the techniques themselves that you employ makes your work different than those of some of the more "cartoony" comics memoir makers out there? Your work seems to share some of the somber qualities that Gabrielle Bell has, and some the self-lacerating qualities that Jeffrey Brown exhibits, but at the same time it also feels very different. Is that at least in part because of the way you approach the visual aspect of the work?

SPURGEON: Do you think the techniques themselves that you employ makes your work different than those of some of the more "cartoony" comics memoir makers out there? Your work seems to share some of the somber qualities that Gabrielle Bell has, and some the self-lacerating qualities that Jeffrey Brown exhibits, but at the same time it also feels very different. Is that at least in part because of the way you approach the visual aspect of the work?

STEVENS: It probably is. The naturalism of my imagery goes hand in hand with the dialogue and I think creates a more realized mood of the characters. There isn't that perverse quality of childhood innocence that lurks over the more cartoony looking autobio work. I find a lot of my peers are drawn towards that certain style, pared down and crude. I find it to be limiting.

SPURGEON: This might be kind of a dicey area, but I don't see your work in the anthologies and other than the brief stopover with Alternative Comics before it settled into present white dwarf state, I can't remember you working with any established comics publishers or collectives. Is there a reason for that, do you think? Could you see yourself in partnership with publishers like that at some point in your career?

STEVENS: I'm not sure what the reason is. I would very much like to work with a

Drawn and Quarterly,

Fantagraphics, or a

Top Shelf type. I've never been asked to be in the anthologies either. I guess I'm just not on their radar, or maybe my work is too artistic for them, too edgy or something.

SPURGEON: You mentioned David Chelsea in passing... how big an influence is he? There's certainly an overlap in tone and subject matter regarding each of your best-known works, and you're both trained artists that bring those skill-sets to your comics.

STEVENS: Yes, I love David Chelsea's work! I was definitely reading and re-reading

David Chelsea in Love throughout the project. Genius stuff. I had the pleasure of meeting him briefly at

Stumptown in '08, which is where I picked up the book actually. I had always been aware of it but could never track down a copy. We're friends on Facebook, and correspond every now and then. He's turned me on to some great golden-age era pen and ink illustrators.

SPURGEON: Are the

SPURGEON: Are the Lodger

strips revelatory to you at all, once you've had some distance? Do you read the strips and suddenly think, "I had no idea I was so depressed" or, "Hey, look how happy I was" or anything similar? What is it like having this involved of an artistic mechanism aimed at your own life?

STEVENS: Yes, when I do look back, I do have a clearer sense of self. Mostly though, I think about what I left out of the story. Things that I was too shy to include because I didn't want to offend the people closest to me. Which is, for me, the biggest limitation of the genre.

SPURGEON: How refined a sense do you have of what your books says about you and the situations in which you've found yourselves during the time represented in the book? Do you know when you give the book to someone that they'll have a specific, definable insight into your life, or do you have any idea at all how someone will react. For that matter, how do your circle of friends and acquaintances react to this work?

STEVENS: I'd say it's about half accurate. I consider the book to be rather lighthearted and domestic, which is what my life became when I moved into Tony and Natasha's. The other half of the story -- the darkest parts -- I decided to keep out because of what I was saying before about stepping over boundaries.

SPURGEON: You're part of my Holiday Interview Series, and one thing I'm talking with as many people as I can remember to is vocation, or jobs, what it's like to fill up a certain amount of your life on an artistic activity like comics and the range of viewpoints that comes with this kind of devotion. I get the sense some time from younger artists that there's a point where they're being published and where their work is starting to be something they can employ on their own behalf in whatever direction they wish, and yet there doesn't seem to be any signs as to what to do beyond that. Are you a lifer, Karl?

SPURGEON: You're part of my Holiday Interview Series, and one thing I'm talking with as many people as I can remember to is vocation, or jobs, what it's like to fill up a certain amount of your life on an artistic activity like comics and the range of viewpoints that comes with this kind of devotion. I get the sense some time from younger artists that there's a point where they're being published and where their work is starting to be something they can employ on their own behalf in whatever direction they wish, and yet there doesn't seem to be any signs as to what to do beyond that. Are you a lifer, Karl?

STEVENS: I have long ago accepted the act of creating comics as my life's work, that includes the painting too, which again I feel is an extension of the work. I can't really see a future where I'm not working in the medium on a consistent, day to day basis. You might say it's hard-wired into my blood. I think there will always be ups and downs financially, but hey, that's par for the course in any artistic endeavor. My confidence to go forward has never changed. I just would like to be a regular producer of beautifully illustrated personal stories that will hopefully continue to find an audience.

So yeah, Spurge, I'm a lifer.

SPURGEON: I'm intrigued by that response, because the bulk of the people that stay in comics for an extended period of time seem to have be part of a group of contemporaries, and you seem to stick out on your own. Are there cartoonists out there, particularly those roughly in your peer group, with whom you feel sympathy or a common cause?

STEVENS: I do feel rather alone, but I feel like it was always like that. When I first moved to Boston in 1999, I hung around some of the

Highwater guys. Tom Devlin was still working as a clerk at

The Million Year Picnic in Cambridge and I would stop there on my way home from work a lot to chat. I never really felt like I fit in with his aesthetic though, I remember once pronouncing (as 20 year olds sometimes do) that I wanted to be the Rembrandt of comics and he just gave me a blank look and said "who's Rembrandt? I only know comics." Anyways, I would bug him a lot to publish what I was doing, which looked like early cruder versions of what I'm basically doing now. He would always pass, but I guess he was under a lot of financial juggling from what I read recently.

Other than that, I like

Lauren Weinstein and

Vanessa Davis's work; we often hang when we cross paths at cons or openings.

Tim Kreider is someone whose work I admire and who I hang with. But I guess, no, I'm still the lone wolf.

*****

*

The Lodger, Karl Stevens, KSA Publishing, softcover, 96 pages, 9780615380841, 2010, $19.95

*****

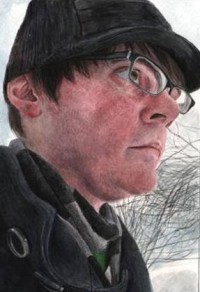

* photo provided by Stevens

* all art is from

The Lodger, including cover

*****

*****

*****

posted 12:00 am PST |

Permalink

Daily Blog Archives

November 2019

October 2019

September 2019

August 2019

July 2019

Full Archives