January 10, 2011

CR Holiday Interview #20—Jaime Hernandez

CR Holiday Interview #20—Jaime Hernandez

Editor's Note:

Editor's Note: My favorite cartoonist. Most of the material discussed here was collected this year into

Angels And Magpies, the latest edition of the paperback-collection series of

Love And Rockets. Please forgive the adjustment in art and if the Internet has moved past any of the following links. -- Tom Spurgeon

*****

Jaime Hernandez is a widely-acknowledged legend of alternative comics and deserves every last bit of attention and approbation that comes his way. He has been applying his formidable reservoir of craft skill towards the creation of great comics for more than three decades now. Among his most famous major works are

The Death Of Speedy,

Wig Wam Bam and

Chester Square, collections of material from one of the ten best comic book series of all time,

the first volume of Love And Rockets. Hernandez is also a long-acknowledged master of the comics short story: "Tear It Up, Terry Downe," "

Spring 1982" and "Izzy In Mexico" among them. His are the only comics about which my friends and I leave each other phone messages and e-mails discussing plot points that sound like we're gossiping about real people. They're real to us.

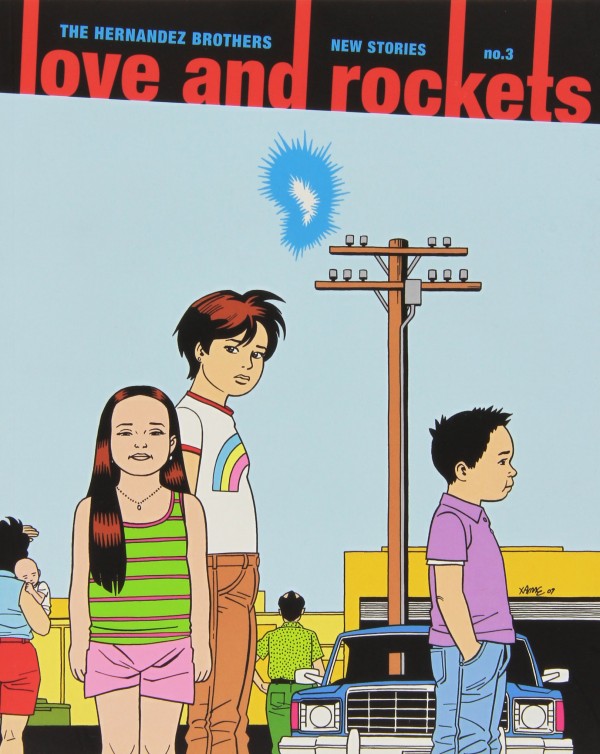

Hernandez' two interlocking tales in this year's

Love and Rockets: New Stories #3, "Love Bunglers" and "Browntown," provided 2010's most powerful 1-2-3 punch and may just be the greatest comics in Hernandez' long and distinguished career. As the critic Jeet Heer

points out, that means they're among the best in comics history. "Browntown" in particular carries all of the weight and emotional laceration of past Jaime work, executed with a refined, stunning precision that tells in some 30 pages a tale that hits like 300 pages of plot and thematic development. I'm honored to close this year's holiday interview series with the amazing Jaime Hernandez. -- Tom Spurgeon

*****

TOM SPURGEON: The comics you published this year, the

TOM SPURGEON: The comics you published this year, the Love and Rockets

work, came in the third issue of the new annual format. Do you miss the comic books at all? Do you miss that format?

JAIME HERNANDEZ: Yeah. Yeah, I do. I kind of miss a comic

hopefully coming out regularly. Even if it was like three or four months apart, it seemed regular: having an issue there, and going through that one, and then the next one pretty soon after that.

SPURGEON: Has switching formats had an effect on the way you work? One of your peers told me -- a cartoonist that hasn't yet cut ties with pamphlet comics-making -- that he dreaded one day having to do that much work before seeing it published in print. He thought it was a boon to more regularly publish just in terms of the psychological toll that comes with making comics.

HERNANDEZ: Yeah. [slight pause] I've learned a lot. [laughs] A lot of it is frustrating: working towards one big deadline instead of a lot of little ones. It's changing the way I'm putting the work down. I miss the freedom of screwing up. If I screwed up in one issue, I could fix it in the next. Now since people have to wait a year for the next work, it's like I can't make any mistakes. I can't leave anything out because I can't fill it in right away.

SPURGEON: Do you run the risk of tightening up, or being more precious about your work than you want to be?

HERNANDEZ: Yeah, yeah. I'm afraid to put stuff down. I'm afraid to put ink down. In order to get it out for

San Diego, which is usually our goal, I'm going to be busting my ass for these next few months trying to finish, even when I gave myself a head start last year. Because most of it is still in pencil stage -- light pencils, because I'm afraid I'm going to change it. Things like that. I used to slap it down, you know, and then see what came next. Now it's like I'm real cautious, so the work backs up and I'm there hurrying every day to meet that deadline. [laughs]

SPURGEON: One thing that you can do with this format that might not have been achievable in a shorter comic publication is that you have these two lengthy stories, "The Love Bunglers" and "Browntown," and one accompanies the other. "Love Bunglers" is split into two parts around "Browntown," and reading "Browntown" changes how we read that second half of "Love Bunglers." How did they become two different stories? They do complement each other and can be read as one longer piece, but they're not presented that way except by proximity. How did you develop this way of approaching those two works?

HERNANDEZ: At first it was going to be two separate stories. Period. I thought the Maggie romance stuff, the modern-day stuff, was a little weak only in that she's been falling in love since the first issue. [laughter] Even if I try to make it fresh and everything, I know it's still Maggie falling in love again. Again. Oh boy. What do we have this time? So I kind of used the other story to strengthen it, linking them together even if it was just within conversation. And also, I hate to say it, but I do think about it being collected now. I didn't use to. I didn't use to care. Now I picture that one of these days it will be a 120 page "graphic novel" and it will all be cohesive and blah blah blah.

SPURGEON: Will you collect it the same way, with "Love Bunglers" split around "Browntown"?

HERNANDEZ: Yeah, I will do that the same way. Partly, in a way, the new one I'm working on is connected as well. That's difficult because I'm trying to keep "Browntown" its own thing. I was really happy with it as a single piece and I got a lot of good response from that. I didn't want to screw it up with something else. Intruding. [laughs] So I'm being really careful with that. That's another reason I'm racking my brains doing this second one. It's almost like I have to live up to that last issue.

SPURGEON: Were you pleased with the response? My memory is that a bunch of readers were immediately taken with the issue, "Browntown" in particular. I assume some of that got back to you. There's so much work out there these days it's difficult for one story to make an impression, and yet I thought that one really did.

SPURGEON: Were you pleased with the response? My memory is that a bunch of readers were immediately taken with the issue, "Browntown" in particular. I assume some of that got back to you. There's so much work out there these days it's difficult for one story to make an impression, and yet I thought that one really did.

HERNANDEZ: Yeah, I was really pleased. I guess I was pleased because it was one of those stories that kind of just fell into place by itself. Where I was watching it happen. [laughs] I remember writing, putting stuff down on the page, and going, "Oh my God, this has three meanings. That's

wonderful!" [Spurgeon laughs] "It's all more than just a single scene. It all kind of fits." I was really happy with that, putting that together, and then seeing that it was successful for other readers, readers that were very nice to it? [laughs] That was the payoff. Like "Oh, boy. I did good."

SPURGEON: The precision of the story I thought remarkable because, as you say, you can watch multiple themes and narratives playing themselves out at once, all with this graceful economy that makes it feel effortlessly paced. Is there a place where that story started

for you, something you wanted to see, or was it all of the issues and the characters and the sense of place at once, more of an overall feel? Where did this one begin?

HERNANDEZ: Actually, it was a story that was stuck in my head since way back in

the seventh issue of the original Love and Rockets. It was one panel in the story "Locas" where Speedy is telling his friends about his sister and kind of talks about Maggie as well. He says, "Then she moved away for three years. And then she came back and she was 13; she was a teenager." That always stuck with me, I thought, "What are the missing years in Maggie's life? What happened those three years?"

One is that it was kind of a desert town. So that helped simplify it. "They've got nothing to do. That's

wonderful." Nothing happened during that time, but everything did. In one of the same panels in that story, these two women are talking about I think Maggie being put to work at the garage. And one lady says, "Well, I raised six kids, too." So there are six siblings in Maggie's family. Later, as the series progressed, I made up five. And I went back and read that issue one day and went, "Oops!" [Spurgeon laughs] "Oh my God! The sixth one!"

In

Ghost Of Hoppers I have all the family together, Maggie's at a family reunion thing, and the brothers and sisters are talking. I have Maggie's youngest brother saying Calvin ran away at 16. He was a criminal, kind of. I made up that brother that wasn't around because I didn't write him. [laughter] I made him up right there, and in the back of my head since then I kept thinking about her long lost brother, and I started thinking about those three missing years. It just all came together. I think that's why it fell into place, because I had it in the back of my head for so long.

SPURGEON: You talked about this place where nothing happens, where nothing is open and nothing is going on. Was that a place with which you were familiar, that place where the town feels deserted and you're left to your own devices? I was struck by the setting of "Browntown" as compared to some of the other places you've depicted over the years.

SPURGEON: You talked about this place where nothing happens, where nothing is open and nothing is going on. Was that a place with which you were familiar, that place where the town feels deserted and you're left to your own devices? I was struck by the setting of "Browntown" as compared to some of the other places you've depicted over the years.

HERNANDEZ: A lot of it was imagined. I know these smaller California towns that are in the middle of nowhere and are kind of dead towns that I've driven through before. I've never lived there before, but I know the feel of these desert towns... where everything's brown, you know? [laughs] And then visiting cousins I didn't know when I was little. "Why are we at this place?" They lived in kind of desolate areas. It was mostly imagined. I thought about some place where nothing goes on.

Gilbert and me always ask each other, "So, what do you got in the new issue? What's coming up?" And I go, "Well, I got this one story about Maggie, blah blah blah..." and I called it "Maggie in Palomar." I kind of aimed it that way, where I'm like, "Oh, boy. A place where nothing happened." It gives them room to do everything, because there's nothing there. There's no backdrop. Nothing to get in the way of their adventures, their life. That's kind of how that story was able to have so much, yet from nothing. [laughs]

SPURGEON: I wanted to ask you about some of your craft choices. One piece about those comics made a big deal of a panel that also struck me, where the kids are at a movie while the parents are talking out some issues. The older kids are able to focus on the screen -- Esther's crying -- and yet Calvin isn't watching the movie, a reflection of all that he has going on in his life. It's something relatively subtle that some might not even catch on a first glance. Are those things you expect your readers to pick up on, or is it something that you think people may only sense in some indirect way? These can be such small, precise moments.

SPURGEON: I wanted to ask you about some of your craft choices. One piece about those comics made a big deal of a panel that also struck me, where the kids are at a movie while the parents are talking out some issues. The older kids are able to focus on the screen -- Esther's crying -- and yet Calvin isn't watching the movie, a reflection of all that he has going on in his life. It's something relatively subtle that some might not even catch on a first glance. Are those things you expect your readers to pick up on, or is it something that you think people may only sense in some indirect way? These can be such small, precise moments.

HERNANDEZ: It's something I hope they'll pick up on, but if they don't, that's okay because they know what's going on anyway. They know that these kids are kind of bummed out because it's over, they're not going to have their daddy anymore. Or Mommy and Daddy are fighting, something as simple as that. I thought Calvin had more to think about, so I had to give him an introspective look. More pissed off than sad. Or sad and pissed off at the same time. So he had to have something going on more than the rest of them. I thought, "Well, he's looking the other way." [laughs] They're looking one way, he's looking the other way.

If people don't pick up on it, that's okay, but it is intentional and it's something that's important to me. It's kind of like I leave it up to the reader. I give it to them, if they draw a different conclusion, that's fine, too, as long as we all end up in the same place.

SPURGEON: Frank Santoro wrote a short essay about how you were constructing pages and using grids in those stories. I don't want to rehash everything he wrote, but one thing that was striking to me was the way that the rhythm of the story changed when you employed three panels across a page to replace a previous use of two. Is that something you do intentionally, control the narrative flow through page structure?

SPURGEON: Frank Santoro wrote a short essay about how you were constructing pages and using grids in those stories. I don't want to rehash everything he wrote, but one thing that was striking to me was the way that the rhythm of the story changed when you employed three panels across a page to replace a previous use of two. Is that something you do intentionally, control the narrative flow through page structure?

HERNANDEZ: It's also because I never put captions of "Later..." Things like that. Sometimes I know people have gotten mixed up. "Oh, wait a minute. This isn't the same scene."

SPURGEON: So the shifts are a way to indicate a transition.

HERNANDEZ: Yeah. And it's also like I give Ray's moments, they're captions, they're his thoughts, and they're done in a six-panel grid. The regular story, the flow goes to eight. I decided to give Calvin six without captions. I don't know. It's just subtle changes but I kind of do it to keep me interested. [laughter] And maybe to help break up the story. "Okay, now it's Ray's turn."

SPURGEON: There's a throwaway line in Santoro's essay, and I'm certain I'm going to mischaracterize it slightly, but I think he was suggesting that in the sequence with Maggie and Reno in the car you made Maggie a touch less visually compelling so that the reader might focus more on the dialogue and on Reno than constantly looking at Maggie. Is that something you would do, make something less interesting if it better served the story?

HERNANDEZ: I guess some of that might be unconscious. If all of the sudden

the Frogmouth walks in in a skimpy outfit, it's obvious where your eye will go. Whether you like women like that or not. Yeah, I guess I might keep it normal so that you can stay on the subject; you're not interrupted. I don't know.

It's also my love -- which isn't that easy to draw -- of people not doing anything. [laughs] Just talking. How many angles can I give them? The original idea for "The Love Bunglers" was Maggie and Ray's date from the minute he picks her up to the end of the night. It was all going to be done in real time; it was going to be a conversation through the whole thing. You were going to find things out through the conversation. I still kept some of that in, but done in real time it was like, "Oh my God, they're going to be at dinner for five pages?" [Spurgeon laughs] "How many times do I have to draw Maggie that same size compared to the table? I have to draw every glass where it is on the table?" I knew that would drive me mad after a while. So I broke it up. And also by the time I was writing it, I went, "Well, maybe they really don't have that much to say." [laughter] They were going to even talk about how they spent their Christmas. It was a

My Dinner With Andre kind of thing. Drawing nothing is hard for a long time, you know?

SPURGEON: Speaking of degree of difficulty issues, "Browntown" deals in straight-forward fashion with serial child sex abuse. There is a lot of bad art made about devastating issues like that. How wary were you having that be part of your story? How do you treat subject matter like that so it doesn't get reduced to talking about an issue. Is it a focus on an individual character? Were you worried that it might be taken the wrong way or otherwise capsize the story?

SPURGEON: Speaking of degree of difficulty issues, "Browntown" deals in straight-forward fashion with serial child sex abuse. There is a lot of bad art made about devastating issues like that. How wary were you having that be part of your story? How do you treat subject matter like that so it doesn't get reduced to talking about an issue. Is it a focus on an individual character? Were you worried that it might be taken the wrong way or otherwise capsize the story?

HERNANDEZ: The one thing I was worried about I asked Gilbert's advice on because he does this stuff

every issue. [laughter] He's a pro.

I was a little scared to do it. I wondered if all the pedophiles were going to be my fans. I was scared of that, because I've been removed from that stuff for a long time. My stuff has mellowed out a lot compared to Gilbert's. Every once in a while I want to break free, and that's how this came about. But I was a little scared. "Are we going to get in trouble?" Because I don't remember when we used to get in trouble what it was that got us into trouble. So yeah, I was a little worried about that.

As far as putting it in the story, I treated it like I treated all the other stuff. It's life, and I try to think about what they think about between the times, between the raping. Some people live with that. So the raping takes ten minutes and they've got a week in-between until the next one. Life goes on. I try to treat it that way. What does the kid do? He's not sitting in his room for a week. He has to go to school, whether he wants to or not. No matter what's going on. He's not telling his parents, because he'll get in trouble. I think of all that stuff. It's just trying to imagine what happens between the terror -- if it's an ongoing thing that nobody's talking about.

SPURGEON: One thing that struck me and I think other readers is that you made explicit the moment where Calvin becomes violent with his attacker, which is not something we're used to seeing from you. I wonder why you chose to depict that moment in dramatic, forceful fashion.

SPURGEON: One thing that struck me and I think other readers is that you made explicit the moment where Calvin becomes violent with his attacker, which is not something we're used to seeing from you. I wonder why you chose to depict that moment in dramatic, forceful fashion.

HERNANDEZ: I had to think about it, first. Like, okay, first of all I need the kid to have the rest of his life in trouble. I needed some kind of really, really violent... something life-altering that aside from the rape showed that he was on his way to self-destruction. I thought, "Well, usually I let the bad guys get away because that's life." You know? [laughs] "This time, I guess I won't let them get away." I even asked myself if I was getting old and conservative, the "crime does not pay" thing? I thought about that a lot. I also hadn't had one in a while -- that scene earned its place. I don't know, it was something I thought about. I don't usually think too much about that stuff. [laughter]

SPURGEON: Both of #3's stories turn on secrets and people withholding information. Maggie tells her mother the secret of the father's infidelity, and yet she's also keeping information from Ray in "Love Bunglers." The big reveal of the latter story is a secret, too, in a sense -- an astonishing one. I wondered what you thought of these situations. I wondered what your attitude was towards all of these secrets.

HERNANDEZ: Just thinking about my life, my family, my mom was never big on badmouthing family and talking about the evil parts. The history. Only once in a while would we hear about that she had a terrible father, blah blah blah. I would always hear from my cousins, the stories their moms told them, my mom's sisters. And they weren't afraid to tell anything. It was like, "Our family was craaazy!" Drama!

Not a month ago I was talking to my mom and she told me this lifelong secret about her mom. And I was like, "Whaaat? I never heard this one." I look at my brother and he says, "I never heard it, either." That's how some families are. You don't talk about things, even if maybe you did you'd feel better. I grew up in a family where if you opened your mouth, you'd get spanked. Things like that when I was little. Just thinking about it, I saw a lot of good junk to throw at Maggie and her family.

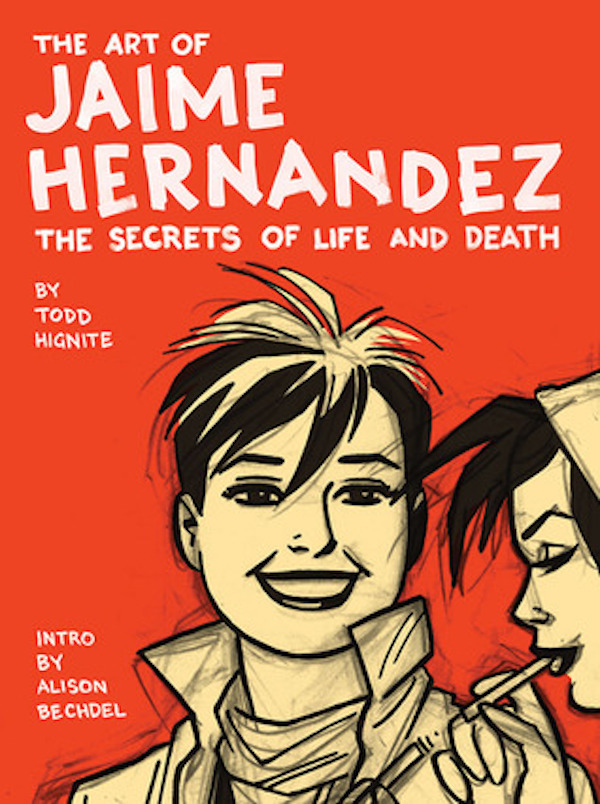

SPURGEON: The art book this year from Abrams, Todd Hignite's

SPURGEON: The art book this year from Abrams, Todd Hignite's The Art Of Jaime Hernandez: The Secrets Of Life And Death

. Do you feel like that's your

book, or is that Todd's book that just happens to be about you?

HERNANDEZ: First of all, I couldn't believe he wanted to do it. Partly because the "art of" is my

Love and Rockets career. Other than sketchbooks maybe. And also I was intimidated. I've said this a million times, but usually I can hide behind my characters and here it was with my name big on the cover. [laughs] Of course I was flattered. I try to make it clear that it is Todd's book. Yeah, it's about me and all the pictures are about me and it's me talking in the book. But he went to a lot of work to put this thing out. He was really into it. When people approach me and go, "Hey, great book!" I'm like, "Well, thanks. But here's the guy who wrote it. This is his book."

SPURGEON: There was a lot of illustration work in there I hadn't seen. In general, is there any way to characterize how doing illustration work might have had an effect on your development as an artist, a cartoonist?

HERNANDEZ: It's a whole separate thing. It's work for hire, and work for hire is not personal. I do take it personally when they edit me into the ground. [laughs] I hate that part. What they want from me is not me, really. I try to keep it separate but I try to give them a good visual because I don't want to put my name on it if it's not. [laughs] But no, it's not personal, it's work for hire. It's like if someone sent me a Spider-Man script and I drew it. As much fun as I'd try to put into it, it's still not mine.

SPURGEON: We talked earlier about your moving from a comic book format to a book format. One of the big issues this year is comics moving into the digital realm, and I wondered if you had any perspective on that at all. One thing I thought about when I considered asking you this question is that your work has been collected so many times that it's almost fitting that there's another collection out there to be had of your work.

HERNANDEZ: Right.

SPURGEON: At the same time, you and your brothers are such print guys. I wondered if you had any opinion on digital becoming the way people read comics?

SPURGEON: At the same time, you and your brothers are such print guys. I wondered if you had any opinion on digital becoming the way people read comics?

HERNANDEZ: I guess if you still allow me to do it the way I've always done it, and this digital thing helps me reach the people I want to reach? Then it's fine. I've gotten to the point where I've stopped arguing about how I'm going to be printed, because I'm not going to argue with the market. [laughs] We went annually because of the market. I can't argue with it if it's going to help me get it out there and sell books. Thirty years ago I would be laughing at myself right now.

SPURGEON: You were more forceful about those issues back then?

HERNANDEZ: No, I just had nothing to lose then. I wasn't responsible for anybody but myself. I thought, "I'm going to do comics and see where it goes." Now I have to think of the bigger picture.

*****

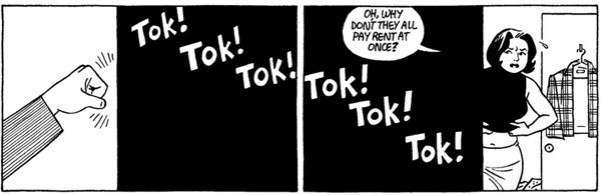

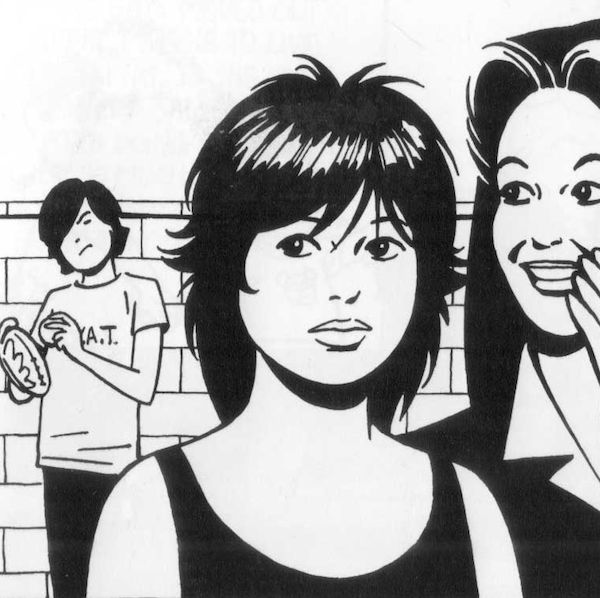

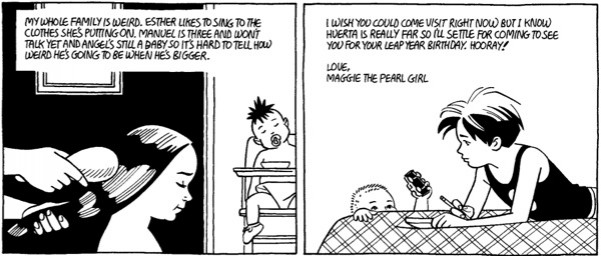

* various beautiful Jaime images from the period in general examination; photo is by Whit Spurgeon

*****

*****

*****

posted 4:00 am PST |

Permalink

Daily Blog Archives

November 2019

October 2019

September 2019

August 2019

July 2019

Full Archives