August 10, 2012

Spider-Man At 50 Part Four: A John Romita Sr. Interview From 2002

Spider-Man At 50 Part Four: A John Romita Sr. Interview From 2002

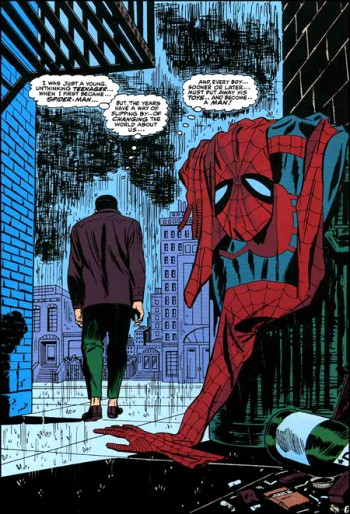

My favorite

Spider-Man artist is John Romita, Sr.

John Romita Sr. may not have been the rock upon which Marvel Comics was built, but the city on that rock has Romita as its basic infrastructure. A stellar costume designer and an incredibly prolific penciler, inker, and cover artist, Romita infused romance comics

élan into the sturdy moral soap opera of the Stan Lee/Steve Ditko Spider-Man. The result was one of the great runs in mainstream comics history. When people one day look back and remember Marvel Comics as a publishing phenomenon, they are likely to think of Romita's handsome men and incredibly great-looking women, clad in the latest fashions, taking the time between super-fights to congregate at the coffeehouse.

It's been my great pleasure to talk at length with Mr. Romita not once but twice. This is our conversation from 2002. -- Tom Spurgeon

*****

Doing His Share

TOM SPURGEON: How often do you get to the drawing table these days?

JOHN ROMITA:

Doing His Share

TOM SPURGEON: How often do you get to the drawing table these days?

JOHN ROMITA: As little as possible. [laughter] That's why I didn't get the cover done in time for solicitation. I feel terrible about it. I should've gotten it done quicker, but between Thanksgiving and Christmas confusion, I thought I was going to have two weeks or a week to get things done, and it ended up a couple of days between one thing was finished and the next thing started. I've had relatives here after Thanksgiving, and then I'm getting relatives here early for Christmas. So things have been up in smoke.

SPURGEON: It's a short holiday season this year, so I think a lot of people are getting squeezed. Do you draw for pleasure still at all?

ROMITA: The only thing I'm about to embark on is to try some computer-generated art. But that's only because it's been in my head for five or six years, that I wanted to try it. I don't know if it's wise, and of course the equipment costs a lot of money, and I don't know if I'm going to have the patience to sit at the computer for long hours. Right now I just use it for e-mail and the occasional reference call. That's the only thing I'm planning.

I did a Supergirl cover for DC, only because a former Marvel editor was up there, and she asked me to do it, and I did it as a favor. But I'm trying to avoid work. [laughter] After 55 years... I started working when I was 14, and when I hit 66, I left the office but I kept working the last five or six years. And I said, "You know, this is ridiculous. Almost 55 years I've been working. The hell with that. I did my share.

SPURGEON: What was it you did at 14?

ROMITA: I was a messenger in Times Square... documented in one of Roy Thomas' nostalgic visits. He did retrospective things while he was editing at Marvel. He did a Captain America/Sub Mariner World War II story, and he showed a scene of me delivering packages in Times Square, believe it or not. [laughs] I wish I remember what book that was.

SPURGEON: How did a Brooklyn boy end up working down in Times Square?

ROMITA: I went to school in the city. When I was 14, I embarked on a long subway ride to get to the School of Industrial Arts in the city. I wanted to go to that art school so badly, so my mother gave me the permission. Somebody asked if there's anybody interested in 60 cents an hour as a messenger, and I jumped up like an idiot. [laughter] For the next few years I worked there, I was a little mad at myself, but I needed the money.

SPURGEON: You were a kid that always drew?

ROMITA: Oh, yeah. I was drawing since I was about five.

SPURGEON: And it was very much supported in your family? Were there artists in your family?

ROMITA: They were supportive. We were musically oriented. Everybody loved singing, and I'm the only one in the family who couldn't sing. They always supported me. But they never believed I would make a living as a comic artist. My father used to say, "Sure, you want to draw, you can draw all you want, but you're not going to make a living." He expected me to become a baker and drive a delivery truck.

SPURGEON: How long did that last?

ROMITA: He talked about it all during my adolescence. My mother used to shake her head while he wasn't looking. [laughs]

SPURGEON: Were you known in the neighborhood as the kid who draws?

ROMITA: I used to draw on the sidewalks of Brooklyn. Believe it or not, I used to get chalk donated from all of my friends. I would do drawings all day long, when there was nothing else to do. There was not much else to do -- no television, and spring and summer and fall I'd be drawing on the streets. The blacktop was a great blackboard for me. I once did a 100-foot long drawing of the Statue of Liberty. It was a good exercise, come to think of it. Hunched over and drawing... I did everything. The whole thing. The pedestal, the full statue, the torch, and I went from one manhole to the next. Which was about a hundred feet.

SPURGEON: I imagine the impermanence of that might have prepared you for comic books.

ROMITA: When it rained, everybody used to say, "Oh, there it goes." I would just do another drawing the next day. It didn't matter.

SPURGEON: You drew in school?

ROMITA: In school I did the usual things. Every holiday, starting with Lincoln's birthday and Washington's birthday, I would do silhouettes of the presidents and other kids would cut them out. I would do backdrops for school plays, and scenery -- that kind of stuff.

SPURGEON: What was your curriculum like at Industrial Arts?

ROMITA: It was an innovative idea -- and by the way, a lot of my colleagues, the comic book artists from the '40s and '50s, graduated from that school. Carmine Infantino, Joe Giella, Sy Barry, almost all of my colleagues went to that school. Just a couple -- John Buscema and Mike Esposito, maybe another couple -- went to Music and Art. Music and Art was an interesting school, but it taught more of the fine arts and printmaking than commercial. I went to the one that was commercial, because I knew I had to make a living.

SPURGEON: You were taught by professional artists there.

ROMITA: That was the theory. And it was wonderful. They were all excellent, excellent teachers and wonderful role models because they were all practicing, earning artists.

SPURGEON: Was it at this point that it locked in for you that you could make a living doing art?

ROMITA: Teenagers are very strange. You don't have to really convince yourself, you just have this vague impression you're going to make a living someday. Even if I thought on lucid moments that I probably wouldn't make a living as an artist, I always thought that this was something I like to do, and I'll always be able to do it, and if I don't get work at it, I'll do production or something like that. One of the things that was good about that school is that it taught you lettering, it taught you mechanical drawing, and sculpture, and photography... the foundation course the first year was very, very complete. It taught me all sorts of things. Like the rest of the classmates, we would grumble and say, "What the hell are we doing photography for?" Or show-card lettering. But the truth of the matter is that everything I studied in that foundation year has come to my aid in comics. Almost immediately when I got into comics, I was using lettering, I was using perspective, I was using mechanical drawing techniques. Everything I was learning in that class -- and I only went there for three years, because I wasted my first year of high school in a local junior high. So I went to Industrial Art at the 10th grade level, and I only did the 10th, 11th, and 12th grade years. To my eternal regret. I should have had the guts to take a final year. Another year -- I don't know if they would have let me. [laughs]

Analyzing Comics

SPURGEON: You were born in 1930, as I recall.

ROMITA: Yeah.

SPURGEON: So you would not have been in the first generation of professional cartoonists.

ROMITA: No. Another one of my regrets. It really is. I always felt that I became a follower of necessity. Because they had already done the ground rules. And I became a guy who was just following everybody else's lead. I think I would have been more of a pioneer and more of a person in my own right rather than a follower. I think it stamped me forever. No matter what success I've had, I've always considered myself a guy who can improve on somebody else's concepts. A writer and another artist can create something, and I can make it better. I don't know the name of that company that advertises all the time, "We don't make the material, we just make it better." You remember that commercial?

SPURGEON: Sure.

ROMITA: That's the way I've always thought of myself. I don't consider myself a creator. I've created a lot of stuff. But I don't consider myself a real creator in a Jack Kirby sense. But I've always had the ability to improve on other people's stories, other people's characters. And I think that's what's made me a living for 50 years.

SPURGEON: You would have been right at the first age to experience that first wave.

ROMITA: It was wonderful, that first wave I was an avid reader. I remember everything that was done. I remember George Tuska... when I was nine and ten years old, George Tuska was doing stuff for Lev Gleason. I remember Jack Kirby's work, I remember Captain America #1. And I had two copies of Superman #1 -- Action Comics. But I was about eight years old when Superman #1 came out. I bought two copies of it. I don't know what reason I gave my parents, maybe it was an accident. I had two copies, and I kept one in a wax paper bag. As a protector. So I was way ahead of everybody else on that. [laughter] The other one I traced to death. The cover was absolutely unviewable, because I'd just traced it forever.

SPURGEON: You were making distinctions between the artists?

ROMITA: I was aware. That was one of the things that I accepted without thinking. In retrospect, it was a blessing. My friends, if you're ten years old and you're talking with your friends about comics. I used to hear my friends say, "You don't think somebody drew every panel in this book. This is drawn mechanically." And I'd say, "No, they're doing the drawing." So I was aware that people were doing 150 drawings a month on these stories, and they were not aware. They always thought it was some kind of trick of photography.

I was also aware of every trick that everybody used. When Jack Kirby's Captain America started bursting out of panels, I was aware that that was smarter than the normal, run of the mill dull stuff where every figure was trapped in a panel. I had a power of understanding. For instance, when I was 13 and devouring Milton Caniff and Terry and the Pirates, I was aware of every little trick he did and realized they were tricks. Where he put his background elements, where he put his foreground elements, where he put accent and shadows. I was aware of every single thing. Where the clouds break on the mountains. Everything. I'm talking about 13 years old, and I'm transmitting everything that Caniff was doing. All the cleverness was going right into my brain. [laughter]

SPURGEON: Was it his facility that he appealed to you, the fact that he was a master cartoonist?

ROMITA: He had a really simple style. It was immediate to me. I loved the fact it was so lush. In other words, it was so powerful with blacks -- nice big juicy blacks. Other people were doing linear work, the normal cartoonists were doing linear work that without color looked really flat. His dailies were excellent, and his Sundays were even better. The thing that gets me about Caniff, and which stamped me also as a storyteller rather than an artist, is that I would always start out looking at Caniff for the artwork. I would devour the artwork for an hour. And then I would get lost in the story. Down through the years, whenever I look back through my Caniff collection, I start looking at the drawings, admiring them and enjoying them, and by the third or fourth panel I'm hooked on the story. And even though I've read it ten times, I will read it again. Because he was more of a storyteller than he was an artist. He was a wonderful artist, but he was a great storyteller. He was a filmmaker on paper. And that stamped me as a storyteller. From that moment on, I instinctively realized that storytelling was more important than drawing.

Santa Claus and Stan Lee

SPURGEON: Now was the comics field encouraged at Industrial Arts?

ROMITA: Interestingly, there was a cartoon class before I got there. There were only three people enrolled in the cartoon class when I got there in '44. Actually, it was '45, because the foundation year I didn't have a specialty. When you chose your major, in '45, there was not enough of a cartoon class. So they stuck us in the corner of the illustration class. It happened to be a book illustration class, which I thought was rather old-fashioned, but I learned to respect it. A wonderful book illustrator named Howard Simon was the instructor. He had me absolutely enraptured with his instruction for that first year. But I got hooked a little bit on magazine illustration, because it was in color. And the second year I switched to magazine illustration. It had an excellent instructor named Clemons, Ben Clemons. So I forgot my cartoon plans, they were completely lost after the first year of book illustration. Then magazine illustration strayed me even further from it. And I didn't think of getting back into cartoons. I decide to become an illustrator.

When I got out of school in '47, I went to work at a litho house. I did coke bottle and coke glasses. And Santa Clauses. I was just an office boy, but I was doing touch-ups on some major artwork.

SPURGEON: This would be in the style of Sundbloom?

ROMITA: Yeah. Sundbloom and Anderson. Beautiful, lush, sunlit figures... remember?

SPURGEON: Sure. That was really the end of the golden age of magazine and advertising illustration.

ROMITA: It was the golden age. Robert Fawcett, Al Parker, all the wonderful, wonderful illustrators of the '40s in the Saturday Evening Post. I lived in the Saturday Evening Post for five years. I thought I was going to be another Robert Fawcett. As an illustrator, I started drawing in that style. I didn't have the knack for painting that I had developed in my first three years in litho, I had gotten pretty good with some painting. But then I started to slip into more of an illustration style in line and color.

SPURGEON: Did you have the same kind of analytical approach to that kind of art as you did to the comics art?

ROMITA: Yeah. I also judged artists by their design sense and their characterization. So the narrative was still there lurking, because a good illustrator has to tell a story, but some illustrators disregarded that and just did show stuff. They were showing off their technique and their color. The ones that appealed to me were the great illustrators.

SPURGEON: How did you end up getting back into cartoons?

ROMITA: When I was still at the litho house, some of my fellow SIA graduates, I met him on the train. We talked, and before I got off the train he said, "You know, I'm working for Stan Lee." He was an inker. He was making a living as an inker, making a nice buck. I was making $25 a week, and I think he was doing $150 a week. He was bragging to me, and he was just an inker! He said Stan Lee was looking for guys to pencil, and he could get more work if I turn in pencils. So what he did was he asked me to ghost for him. I would pencil for him, and he would represent it to Stan Lee as his own. So I ghosted for him for about a year and a half. I was working for Stan Lee for that year and a half, and Stan Lee didn't know me. Until I got drafted. After I got drafted, and I spent time in Fort Dix, and I got assigned to New York on Governor's Island in the recruiting poster department, which was a lucky break completely out of the blue. I got back into illustration that way. I was doing comics in my spare time. And while I was in the Army I went up to Stan and got work on my own.

SPURGEON: He was in the Empire State Building office at that time?

ROMITA: He was in the Empire State Building when I first started working for him, and I can't remember where he was after that. But the first time I was working for him as a ghost he was in the Empire State Building. I remember many times waiting outside the Empire State Building for my partner to tell me how the work was accepted.

SPURGEON: Was this a common practice?

ROMITA: There were a lot of guys ghosting. It was a common practice in syndication, anyway. A lot of inkers who were very quick as inkers but not good storytellers, or they couldn't do it fast enough even if they were good artists. They weren't fast enough. The ones that were fast made a living as pencillers. They needed something to break the ince, to get the work on paper, and then they could ink it. So yeah, it was prominent. So I ghosted for some of my colleagues in the romance departments. I ghosted for other people, too. Don Heck once ghosted for me, once, when I hit an artist's block. I couldn't produce anything for about a week. I begged him to help me out, and he did a beautiful pencil job.

SPURGEON: Were you becoming aware of the community of cartoonists working in comic books at this time?

ROMITA: Oh, yeah. I was not as gregarious as I should have been. I was a little bit sheepish, a little bit shy. I was 20 years old, in fact I was 19 when I started. I used to go up and wait in the waiting rooms, and listen to the other people talk who had more experience. I remember Davey Berg, and Jack Abel, and Gene Colan and guys like that, we were always there for somebody to throw us a three or four-page bone. It was shaping up on the docks like a longshoreman, you went there hoping to get work, and if you didn't get work, you just went without income for a couple of weeks.

SPURGEON: Now you decided to no longer ghost when you were in the Army?

ROMITA: I thought about getting work by myself almost immediately after I got to Governor's Island. As soon as I got settled in, I went uptown in uniform, because I had a Class A pass. I presented myself to Stan Lee's secretary, and said, "I've been working for Stan for a year and a half and he doesn't know me." And she came out with a script! Not only that, but she came out with a script and she expected me to ink it, too. That was the first story I ever inked for Stan Lee after penciling for a year and a half.

SPURGEON: I assume this one of the knock-out secretaries that Stan was famous for.

ROMITA: Oh, yeah... [laughter] A blonde. Oh, was she gorgeous. It used to stop my heart just to talk to her. The next time I went up I remember he had a beautiful brunette. He always had good-looking women there.

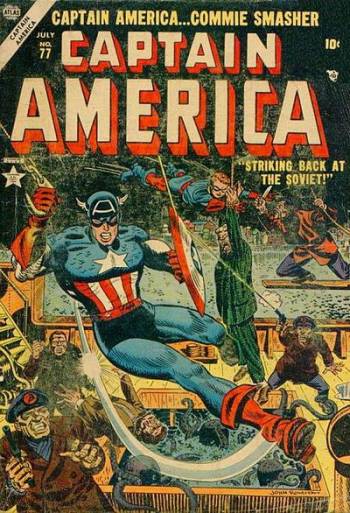

While I was in the Army, that was even when I did a short run on Captain America, in the mid-50s, '53. I was just getting out of the Army just as the Korean war came to an end. I got out of the army in July of '53. I started doing westerns at that time.

Dream Come True

SPURGEON: Now was doing Captain America a thrill for you having admired Kirby?

ROMITA:

Dream Come True

SPURGEON: Now was doing Captain America a thrill for you having admired Kirby?

ROMITA: It was a dream come true. All I did was frustrate myself because it was never good enough for me. It was hard for me to do it. I wanted it to look just like Kirby. And I ended up sort of having a mish-mosh between Kirby and Milton Caniff. I couldn't help myself, because I thought like Milton Caniff even though I admire Kirby's Captain America. So I always felt responsible for the failure of that book. Stan told me it was not, it was a political decision. Captain America had hit some very rough periods there. Patriotic was a bad word, and the flag was a bad word in the middle 1950s. So there was a backlash against Captain America. The other two titles, the Human Torch and the Sub-Mariner which Everett came back to do continued for a year or two after Captain America was dropped. I always felt like a terrible failure. Stan always told me it had nothing to do with the artwork, he loved the artwork, he said it was politically unpopular.

SPURGEON: Did you have a different perspective on what was good in the art form at this time? There were different artists working in different modes than when you were analyzing the field as a reader.

ROMITA: When you're doing the work, you don't have the time for reflection and theory. You're just glad to get the pages out. And the quicker you get the pages out, the quicker you get the check, and the quicker you get the next story. So what happen

posted 6:00 am PST |

Permalink

Daily Blog Archives

November 2019

October 2019

September 2019

August 2019

July 2019

Full Archives