October 12, 2008

CR Sunday Interview: Bill Schelly

CR Sunday Interview: Bill Schelly

*****

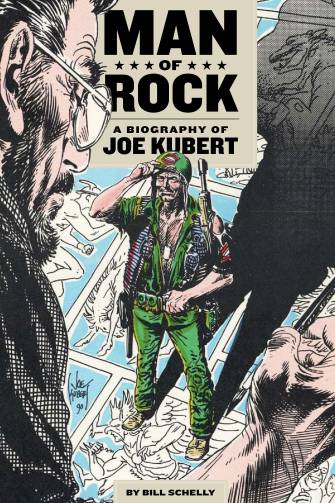

I enjoyed

Bill Schelly's new book on Joe Kubert,

Man of Rock, that will be rolling into bookstores and comic book shops this fall. The comics historian's lengthy disquisition on a living comics legend proves to be a very traditional biography, a fitting choice given that its subject is one of the foundational talents of American mainstream comic books in part for his strong adherence to comics' core values.

Joe Kubert

Joe Kubert has been successful at nearly every stage of his long career. He entered comics during its early shop stage and developed into a workhorse by the time he finished high school. He was one of the industry's few artist/businessmen. While he never displayed a significant desire to work anywhere other than in the strips and comics that so influenced him as a youth, he's as well known for

the art school that bears his name and instills his artistic values as he is for any single comics work. As an editor at DC comics, one of the first in a wave of modern artist/editors, Kubert was forward-thinking enough to hire the man he replaced because he so valued that man's talent. He's made as many pages of American comic books as any living artist I can name, yet has also contributed to European albums. Kubert has even made a strong, late-career transition into graphic novels, producing among several admirable books the award-winning

Fax From Sarajevo.

Man of Rock gives you a sense of a life in comics very well lived. Bill Schelly's sunny biography, stuffed with family and career and a Thanksgiving parade's worth of important industry figures, captures for posterity Kubert's winning, take-no-guff spirit. I was eager to talk to him.

*****

TOM SPURGEON: Bill, I'm aware your background in fanzines, but I'm not sure a lot of people reading this will be. Can you talk about your personal involvement in that part of comics and how you eventually came to write about comics in other venues and even write about fanzines and that specific part of comics culture?

BILL SCHELLY:

BILL SCHELLY: When I was 13, way back in 1964, I heard about fandom from a letter column in

Justice League of America. The idea that there were people like me who loved comic books, and publications about the comics medium, was incredibly exciting. I began ordering fanzines, and soon was planning my own. That began my early involvement with fandom. As I got older, my self-published fanzines got better. Most people remember me for

Sense of Wonder, which was published from 1967 to 1972. The last couple of issues published early attempts to chronicle the entire career of Will Eisner.

Between the fact that I didn't care for much that DC or Marvel were publishing in the mid-1970s, and coping with life as a young man on my own in Seattle, I drifted away from comics entirely for a number of years. It was only in 1991 when I ran into a guy who was involved in fandom that I realized how much I missed comics and fandom. I was able to get in touch with fans I knew in the 1960s, and before long I found myself collecting old fanzines and researching the early years of fandom. Eventually, it led to the publication of my book

The Golden Age of Comic Fandom in 1995.

While I was writing about the history of fandom, my interest in the comics field in general was thoroughly reawakened. Suddenly I was enthused about comics all over again, though appreciating them from the perspective of a 40-year-old man as opposed to a teenager. With the wealth of reprints that were available, I was able to educate myself through the 1990s to the point where I began writing about the history of comics themselves, along with my fandom stuff. Eventually I did a bunch of introductions for DC Archives volumes, and

a biography of Otto Binder, chief writer of the original Captain Marvel, called

Words of Wonder.

SPURGEON: Can you talk a little bit about your dedication, to Jerry Bails? What would you have a reader of your book, comics readers in general, know about Bails and his work?

SCHELLY: Jerry Bails was more responsible than any other individual in bringing fans together in the early 1960s, through his publication of the fanzine

Alter Ego in 1961, and getting comics fandom started. Through plugs in professional comics, and letter columns that gave the writers' full addresses, and networking with others, Bails built up a mailing list of something like 1600 comics fans by 1964. His efforts inspired others, and things snowballed from there.

But Jerry's real obsession was with indexing all known comic books, and identifying the writers and artists of each and every comic book story published during the "golden age" of comics from the late 1930s to the 1950s. Most of these creators were completely unknown at that time, but he somehow ferreted out their names, and was able to contact many of them. He wanted to make sure that we, as fans, gave credit to the folks who wrote and drew the comics, and dedicated the rest of his life to that effort. As a result, we have his

Who's Who of American Comic Books on-line. His effect on the study of comics' history is incalculable. I only met him once, but I'm sure glad I did. We became email correspondents, right up to the time of his death a couple of years ago. He was an exceptional human being.

SPURGEON: What was the specific trigger, the one thing that moved you to thinking about writing about Joe Kubert to actually writing about Kubert?

SCHELLY: I was trading emails with

Bud Plant, and Bud suggested I do a book on Kubert. I instantly realized that Joe was a perfect subject for several reasons. First, I'm a big fan of his work. Second, his career in comics literally spans the history of the modern comic book. He got his first job just weeks after

Action Comics #1 hit the stands. Third, he's had such a varied career, including starting his cartooning school in 1976, and creating Holocaust-themed graphic novels in more recent years, among many other things. There was just a lot to him, which made him an interesting subject to write about.

SPURGEON: What was it like working with Fantagraphics and Kristy Valenti on this project? I don't think she comes from a hardcore American mainstream background, and I wondered if that maybe gave her a distinct point of view.

SPURGEON: What was it like working with Fantagraphics and Kristy Valenti on this project? I don't think she comes from a hardcore American mainstream background, and I wondered if that maybe gave her a distinct point of view.

SCHELLY: Kristy was a very good editor who helped in smoothing out the text, making sure that if I made an assertion, that I followed it up with supporting examples, and of course checking my grammar and such. This is what I needed, because I had already shown the manuscript to several comic book experts -- including Jerry Bails. Out and out wrongheaded ideas or factual errors had pretty much been dealt with before the book was sent to Fantagraphics. Also,

Kim Thompson went over it, and came up with some very good points which I addressed.

SPURGEON: Can you talk a little bit about your research into contextual issues and how you balanced that with the direct information about Kubert? Like when you talked about Harry Chesler, how did you decide how much to write about him. What are your preferred sources for early industry history?

SCHELLY: A number of the people who worked in Harry Chesler's shop in the late 1930s have been interviewed about it. Some of their firsthand memories are in the book. His foreman

Jack Binder spoke about him in a late-in-life interview. Of course, there are Joe's memories. Unfortunately I don't think Chesler himself was ever interviewed, though he lived in the 1980s. So I had to rely on the firsthand accounts of a bunch of people, some who had differing opinions of the man. Some of those differences are mentioned in the book. Obviously, I prefer firsthand accounts, and I did interview something like fifty of Kubert's friends, family and colleagues. Other times, I relied on interviews conducted by others, such as a great one that appeared in

The Comics Journal.

One of the main reasons I emphasized Harry Chesler in the book is because he came back into Joe's life when Kubert started his school. And his willingness to help Joe when Kubert was a boy was partly an inspiration for the formation of the school. So I found that relationship very significant.

SPURGEON: I thought it was fascinating that some people reacted poorly to Kubert's art when it went through that first initial shift in 1947. How have people in general reacted to Kubert's art over the years? Is there a period that is considered Kubert's absolute best? Do you have a favorite period or assignment that may be undervalued? What do you like about it?

SPURGEON: I thought it was fascinating that some people reacted poorly to Kubert's art when it went through that first initial shift in 1947. How have people in general reacted to Kubert's art over the years? Is there a period that is considered Kubert's absolute best? Do you have a favorite period or assignment that may be undervalued? What do you like about it?

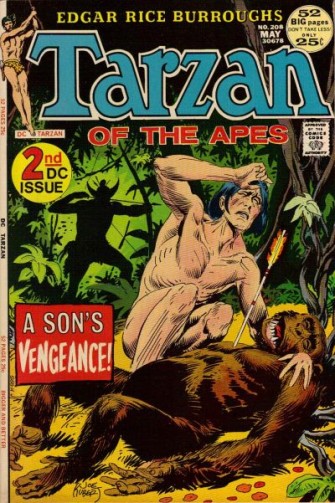

SCHELLY: It's notable that Kubert's art -- what we would call his style -- evolved a lot during the first twenty years of his career. That's not to say that it's been static since then, but from 1942 to 1962 there's a definite, noticeable development. There's an enormous difference between his work on

Hawkman in the 1940s and his work on the same character

in the Brave and Bold revival of the Silver Age. I ran into fans who preferred his earlier work on

Tor in 1953 over his interpretation of

Tarzan in 1973. But then Joe does something like

Yossel in 2003 that is drawn in pencil as if in a sketchbook, and it's yet a different look. So he's mixed it up even after reaching his mature style.

What do I consider Kubert's absolute best? I think he does his best work when he has a good story. I think working on

Bob Kanigher's high-caliber scripts on

Sgt. Rock in the mid-1960s excited Joe and pushed him to do some of his very best work. His 80-page telling of

Tarzan of the Apes is the best sequential art version of the ape-man's origin. I think his work on

Firehair is sometimes overlooked, and it's gorgeous -- especially his use of grease pencil. None of these, of course, involved superheroes.

SPURGEON: One of the questions I've always had about Kubert was how he operated in what was supposedly a rough office at DC during its heyday. You illustrated that through his relationship to Bob Kanigher, and it seems like you're suggesting, basically, that Kubert didn't receive any crap because he made it clear he wouldn't take any. Is that basically how Kubert thrived in that office?

SPURGEON: One of the questions I've always had about Kubert was how he operated in what was supposedly a rough office at DC during its heyday. You illustrated that through his relationship to Bob Kanigher, and it seems like you're suggesting, basically, that Kubert didn't receive any crap because he made it clear he wouldn't take any. Is that basically how Kubert thrived in that office?

SCHELLY: Yes. People just don't want to mess with Joe. I think it's a function of his personal confidence. He exudes it.

SPURGEON: Why do you think Kubert hired Kanigher back as a writer when he assumed editorship over many of Kanigher's books? You suggest something I'd never considered before, that it was part of him declaring independence in that editorial role. Can you talk about that a little bit?

SPURGEON: Why do you think Kubert hired Kanigher back as a writer when he assumed editorship over many of Kanigher's books? You suggest something I'd never considered before, that it was part of him declaring independence in that editorial role. Can you talk about that a little bit?

SCHELLY: I don't know if it was so much him declaring independence as hiring the best man for the job. Kanigher had reached a point where he wasn't what DC was looking for as an editor, but Bob and Joe never had a falling out. And Joe, more than anyone else, realized what an asset Kanigher was, as a writer. Maybe there was a little loyalty there on Joe's part. He may also have felt that he could channel Kanigher into a direction that would be more appealing to modern readers. They seemed to work together well, despite the switching of roles, and I think the war comics did improve after Kubert became editor.

SPURGEON: Can you talk a little bit about Kubert's editing style, how the people he edited considered him in relation to other editors? How much of his editing style was influenced by his own editors, and if so, in what way?

SCHELLY: On the one hand, I'd say Kubert was one to hire the best people and let them do their job without a lot of second-guessing, asking for re-writes and such. He didn't have time. The one area where he would edit scripts, from what I've learned, is reducing the word-count if a writer had been a little too verbose. He would prune and simplify. I don't think he had to be too concerned about the art, because he did use mainly proven professionals like

Russ Heath,

Doug Wildey and

Sam Glanzman.

Joe had one bad habit, and that was making art corrections himself. So you'd have a story drawn by, say,

Murphy Anderson, and then suddenly there's a face that's clearly drawn by Kubert. I guess he didn't want to take the time to have the artist do his own corrections. Or maybe those were instances where there was deadline pressure and there just wasn't time. It didn't happen too often.

SPURGEON: There's an element to Kubert's career that's not prevalent in a lot of cartoonists' careers in that he was at one time a businessman of comics -- maybe not on the scale or with the historical impact of Will Eisner, but there's an element of being a packager and working with certain licenses... what in Kubert's personality do you think has led him to be successful with arranging certain aspects of the business side of his career in various ways?

SPURGEON: There's an element to Kubert's career that's not prevalent in a lot of cartoonists' careers in that he was at one time a businessman of comics -- maybe not on the scale or with the historical impact of Will Eisner, but there's an element of being a packager and working with certain licenses... what in Kubert's personality do you think has led him to be successful with arranging certain aspects of the business side of his career in various ways?

SCHELLY: Kubert grew up during the Great Depression, and this had the effect of giving him a drive to make a little more money than he would otherwise, just sitting at the board. It was a striving for financial security. And in his first job in comics, with the Chesler shop, he saw how packaging was done, so he had an example to follow. It wasn't a mystery.

But I think what happened is that Joe realized pretty early that how one handled one's finances makes a big difference. Two guys who earned the same amount could end up in very different places, depending on what they did with their money. So he put in the effort to learn about business, and about borrowing money, and banking, and investments, and tax law. He found he had an affinity for these things, and the proper discipline, which is probably why he's done very well, while others haven't.

SPURGEON: How do you think Kubert views his own work? What makes

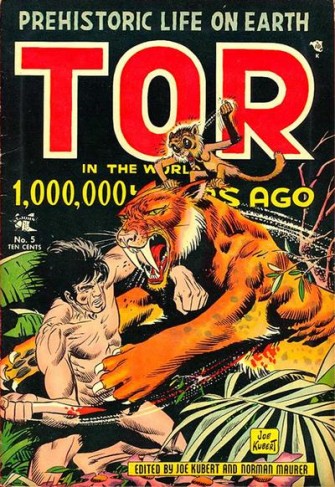

SPURGEON: How do you think Kubert views his own work? What makes Tor

, for example, such a personally important work? Is it the quality of the art? The ability to get as close to conception as he wanted? Does he value the overall narrative impact?

SCHELLY: I think what Kubert values most is the process. He loves the drawing, the writing, the process of creating something. That's where he lives his life. I think that's why he doesn't often say whether this or that assignment meant more to him. Some turn out better than others, but for him it's a life at the drawing board, striving to do something better or more interestingly. He puts a lot of thought into what he's doing.

Tor was the first character that he invented, and has always been very special to him. But more to the point, the theme of

Tor -- the exploration of morality, and man's capacity for good and evil -- has proven to be one of his most central concerns. His later

Fax from Sarajevo and

Yossel explore some of these same themes.

SPURGEON: I think some of the best writing in your book is on his experience with the

SPURGEON: I think some of the best writing in your book is on his experience with the Green Berets

newspaper strip, which is fascinating because it simply didn't work. You don't quite make a firm valuation in Man of Rock

, letting Kubert speak for himself, but how much do you think that it was the frustrating work circumstance and how much do you think it was the politics involved?

SCHELLY: The concept of

Tales of the Green Beret was flawed, because the situation in Vietnam was just too complicated to work as the background of a comic strip. For one thing, the protagonist wasn't a Green Beret, he was a journalist. Then there was the confusion over what the U.S. was doing over there anyway. It just seemed borderline incoherent at times. Joe did make it clear to me that he didn't quit the strip because he disagreed with our country's policies over there. He was turning against the war, but he left because of his disagreement with the writer, Jerry Capp, who was giving him jingoistic scripts which Joe hated. Plus it was obvious that, with the strip losing papers, it wasn't going to last.

SPURGEON: We spoke earlier of Kubert's enormous self-confidence. How does he view cartoonists and comics creators that maybe have not enjoyed his success? There was something that you wrote in an aside -- although I can't find it now, so maybe I'm not remembering it correctly -- that makes me think that he might hold the view that most people bring dire consequences on themselves.

SCHELLY: I don't recall Joe ever expressing something to the effect that others bring about dire consequences on themselves. But he did say that someone who doesn't work hard enough at his craft is probably going to be the one to get laid off first when the comics industry is going through hard times.

SPURGEON: Kubert's work seems to translate into European albums-style comics, which is an entirely different kind of comics making. In other words, I don't look at things like

SPURGEON: Kubert's work seems to translate into European albums-style comics, which is an entirely different kind of comics making. In other words, I don't look at things like Abraham Stone

or even Fax From Sarajevo

and see American mainstream comics bombast. What is it about Kubert's style do you think that allows him a slightly broader range than some of his peers?

SCHELLY: I don't know if I can answer that. It's true that

Sgt. Rock isn't noticeably macho. He's a very thoughtful character, much like Kubert. Joe was born in Europe -- in the Ukraine. Maybe that has something to do with it. As a boy he was very aware that half of his family was over there during World War II, so he's an American with a worldview.

SPURGEON: Ralph Bakshi once told me the thing that impressed him about Kubert is that unlike some of his peers Kubert seemed artistically fulfilled by being a major comic book artist and putting out good work in that part of the cartooning industry, as opposed to some of the lateral moves that might have been available to him because of his talent: into commercial illustration, say. Do you think that's a fair assessment? What is it about Joe's character that's kept him interested in comics and with the school rather than a move to California and animation, or heading off to paint at some point?

SCHELLY: Joe Kubert loves the comics. That's what he's wanted to do ever since he first discovered

Tarzan in the Sunday funnies. His fascination with them seems endless. Plus in comics, a creator has so much freedom. Even with a script written by someone else, no one tells him how to do the work, or looks over his shoulder. He works almost unfettered. That kind of autonomy isn't something you can find in animation or commercial art. I do wish that Joe would do some painting, but that just doesn't seem to interest him. He's a comic book artist through and through.

SPURGEON: Is there a figure in comics you're interested in pursuing next? How about outside of comics? I believe you just did a biography of Harry Langdon.

SCHELLY: I'm writing a book called

Founders of Comic Fandom for McFarland next. After that, I don't know. I'm kind of burned out on writing biographies. I will say that I'm generally drawn to underdogs and under-appreciated people. Kubert is as mainstream as I get. I'm open to suggestions.

SPURGEON: How involved was Joe in this book? I was the Comics Journal

managing editor when Gary Groth did his interview and Joe really worked over that text. Did he provide any advice, direction…?

SCHELLY: The book is my project, and it's entirely my own work. Joe didn't want to be involved in the book creatively. I offered Joe the chance to read it when I was done, just for factual accuracy, but he never did. He told me he found it very difficult to read about himself. Instead, his wife Muriel read it. She had a few small factual corrections.

I had total freedom. Joe said he enjoyed my

Otto Binder book, and he trusted me. Of course, I interviewed him, and he made himself available when I had follow-up questions. He gave me contact info for his sister Roz and his friend Bob Bean. I visited the Kubert School in the fall of 2004, which is where I first met

Adam. But when it came to the text, it's all mine.

SPURGEON: Since you and I last spoke, Muriel Kubert passed away. Is there anything you can point to in terms of her specific contributions to Kubert's life and career that might be different than the enormous impact most long-term, loving spouses make on their partners? Can you talk about her as a figure on her own, particularly as the administrator of the school? What should comics history remember about Muriel Kubert?

SPURGEON: Since you and I last spoke, Muriel Kubert passed away. Is there anything you can point to in terms of her specific contributions to Kubert's life and career that might be different than the enormous impact most long-term, loving spouses make on their partners? Can you talk about her as a figure on her own, particularly as the administrator of the school? What should comics history remember about Muriel Kubert?

SCHELLY: Together Joe and Muriel set up the Kubert School. Muriel didn't have any other help. She shepherded all the applications and paperwork for the school to be accredited -- no easy task -- and handled all the administrative work. I think her efforts to start and sustain the Kubert School are her greatest contribution to the comics field. Sometimes people used to tell her, "You should call it the Joe and Muriel Kubert School," and she'd say, "But who would go to a school named after me?"

Her passing was very sad, and I do wish she could have seen the finished book. But at least she read the manuscript and knew it was going to happen. She did a lot of digging to find some of the cool photos in

Man of Rock. She was a very considerate, caring person.

SPURGEON: Joe's in his early 80s now, and while he's an incredibly vigorous man, people in their 80s are people in their 80s... Is there anything specific he still wants to do, do you think? Is the school set up to outlive him? Is there anyone in the family that you think will be responsible for maintaining his legacy? What should that legacy be?

SCHELLY:

SCHELLY: Joe just turned 82, and you're right, he is a very vigorous man. He will draw comic books until he can't any more, and I think that's a long way off, God willing. He told me his hand control is as good as ever, and his vision isn't deteriorating. He'll continue to be a creative force. I believe after the

Tor mini-series, he was planning to do the second part of his

Jew Gangster project.

I'm pretty sure Adam and Andy would keep the school going, if Joe couldn't, and will be the ones responsible for maintaining his legacy. Joe's legacy is a lifetime of work of exceptionally high quality, a one-of-a-kind artist who ranks alongside other greats of comics, like Will Eisner,

Harvey Kurtzman,

Jack Kirby and

Charles Schulz. Also, I'm sure there will be former students telling stories about their encounters with Joe for a long, long time to come.

*****

Man of Rock, Bill Schelly, Fantagraphics, softcover, 220 pages, 9781560979289, October 2008, $19.99.

*****

* cover to Schelly's book

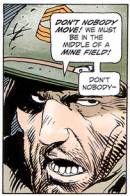

* Kubert panel featuring Sgt. Rock

* Schelly's most famous 'zine

* Kubert draw the Robert E. Howard fantasy characters

* 1950s St. John's cover

* 1970s DC cover

* Kanigher and Kubert on

Sgt. Rock

* the famous 3-D comics title Kubert helped make happen

* Tor, perhaps Kubert's signature character

* from

Tales of the Green Beret

* from

Fax From Sarajevo

* from

Yossel

* the first book in the

Jew Gangster project

* classic Kubert cover featuring Hawkman

*****

*****

*****

posted 8:00 am PST |

Permalink

Daily Blog Archives

November 2019

October 2019

September 2019

August 2019

July 2019

Full Archives