November 15, 2014

CR Sunday Interview: Eric Haven

CR Sunday Interview: Eric Haven

*****

I've been following the comics of

Eric Haven for some years now, so I was surprised when I sat down to prepare for the following conversation I knew absolutely about the cartoonist beyond that he worked for the

Mythbusters. What I found was a pretty common story; we're near same-age peers, he had ambitions like many of the emerging artists of the late 1980s and early 1990s to be a working comics person, since that wasn't in the cards he's adjusted and continued to do work as opportunities and inspiration allowed. Everything else I know you'll know about 20 minutes from now.

Haven's latest comics is

UR, from

AdHouse Books. I liked it quite a bit, and am grateful the Bay Area resident took my questions. -- Tom Spurgeon

*****

TOM SPURGEON: Eric, I've a hard time figuring out a lot about your past on my own. My take is that you're in your mid-forties and were a pretty standard comics reader as a young person. Is that fair? What were your early experiences with comics?

ERIC HAVEN: Yep, good guess. I'm 47 years old, and growing up as a kid in the '70s I had extremely limited access to comics in comparison to today. Obviously no Internet, but also no comic stores or comic conventions. At least not in the Syracuse area.

Luckily for me, my parents enjoyed reading and going to bookstores. One discount store we'd frequent would put unsold newsstand comics in a box for 10 cents each, their covers torn off because the seller returned them to the publisher for credit. It's not precisely legal, but it was a gold mine for me as a kid. For many years, the proper look and feel of comics for me was the coverless guts. If I ever happened to purchase a comic at a magazine stand, I'd tear the cover off when I got home. It just didn't look right to me... too garish, too slick.

Even at the cost of 10 cents each I couldn't afford to buy a lot of comics as a kid so the ones I had were read innumerable times over. I studied the entire comic; not only the story itself but also the advertising and letter columns and editorial pages. After a while I learned to identify the artists -- pencilers, inkers, some letterers and colorists -- without looking at the credits.

Reading the comics over and over again I became obsessed with the

Marvel characters and their interlocking continuum. And the stuff Marvel was putting out then was completely mind-destroying to a kid like me... a heady onslaught of

Man-Thing,

Killraven,

[The] Korvac Saga,

Werewolf By Night,

Panther's Rage,

Deathlok,

X-Men,

Black Goliath, etc. etc.

DC Comics -- or any other comics -- didn't even register. Marvel was it.

If I think of myself as a sword, Marvel was the forge which banged and smashed my brain into a certain shape.

SPURGEON: You talk in one interview about winning a contest for comics, and the disillusion that followed when you eventually discovered there was no money to be had making them as you hoped you'd might. Can you walk me through that extended experience? How did it finally dawn on you that comics might not have a place for you at the time you were considering making them?

SPURGEON: You talk in one interview about winning a contest for comics, and the disillusion that followed when you eventually discovered there was no money to be had making them as you hoped you'd might. Can you walk me through that extended experience? How did it finally dawn on you that comics might not have a place for you at the time you were considering making them?

HAVEN: Shortly after moving out here to the Bay Area in 1989 I saw that the alt-weekly

San Francisco Bay Guardian was conducting a "cartoon contest." I thought I'd give it a shot and drew a one-page strip that featured Little Nemo, Zippy the Pinhead, Calvin & Hobbes, Spider-Man, and others. It won the parody category and a panel from the strip was blown-up and showcased on the cover of the paper the week they published the contest results.

When I saw that paper with my art on the cover, on the street for all to see, I thought, "This is easy!" I quit my day job as a security guard and flung myself into drawing more comics. Which was stupid, because I ran out of money very quickly. I luckily found an office job with regular hours and continued to draw comics in the evening, on weekends, and over holidays. By the Fall of 1991 I had put together a 24-page black and white comic called

Angryman. It ended up getting published by

IconoGrafix, an imprint of

Caliber, in April 1992.

That month I quit my day job, determined to make it as a comic artist. I sat at the drawing board at least 8 hours every day and maintained a pace of about four pages a week. By the time I finished the 2nd issue of

Angryman, the first issue had made it into stores. I was so incredibly psyched to see it on the shelves at

Comic Relief in Berkeley. I had first sold

Angryman there as a hand-stapled xeroxed mini-comic so to see it there now as a professionally-published comic was almost overwhelming to me.

But after seeing what I made on the first issue (precisely $100, still by far the most money I've ever made for a comic book) I realized there was no hope for me to make a living at it. So I went back to the day job and continued to draw comics on evenings and weekends and holidays.

It was depressing to think I couldn't make a living as a comic artist. But I also feel that it worked out for the best: I could draw whatever I want at my own pace, not being tied to a strict deadline or a regular title. I did one more issue of

Angryman before quitting that and focusing on creating mini-comics.

SPURGEON: Am I right that you knew the late Dylan Williams when you were both in the Bay Area? I know he meant a lot of things to a lot of people. What were your experiences like with him?

HAVEN: It's difficult to contemplate the effect Dylan had on my career as a comics artist. I'm not even sure I'd still be drawing comics now if not for Dylan's initial championing of my stuff.

I first met Dylan when he was working at Comic Relief. Right away we started talking about favorite artists and comics. At that time I thought I had an in-depth knowledge of comics and creators, having studied various book collections. But Dylan's knowledge was vast.

It was Dylan who got me fired up on comics again after I realized I couldn't make it as a professional artist. He was so enthusiastic about comics it'd be infectious. After speaking with him my head would be spinning with possibilities. It didn't matter if I couldn't make money at this. It was art.

There were many artists I had never heard of before being shown their work through Dylan. [Mort]

Meskin, [Jesse]

Marsh, [George]

Roussos. [Fred]

Guardineer, [Ogden]

Whitney, [Alex]

Toth. [Harvey]

Kurtzman, [Bernard]

Krigstein, [Joe]

Maneely. You can find their work in two seconds on the Internet now, but back then it was a challenge. Dylan would print collections of the stuff he liked and just give them to people. It wasn't for sale; it was for study.

I know I'm not the only one within Dylan's sphere of influence. When he died I realized a massive, sucking void had been left in his absence.

SPURGEON: How then did you get back into making comics? Because my memory is that I first heard of you when you had done completed work pretty much of a kind with the work you're still doing now.

HAVEN: I've never really stopped making comics since I started in 1985. I've just had long fallow periods between published works. There's almost 10 years between the publication of

Angryman #3 and

Tales To Demolish #1. There's six years between

The Aviatrix and

UR. But in those intervening years I've always continued to make comics. They're just seldom seen.

SPURGEON: I don't know that I've talked to that many people that have the experience of publishing through Alvin Buenaventura, and I believe that at least The Aviatrix came through one of his houses. What was it like doing that book?

SPURGEON: I don't know that I've talked to that many people that have the experience of publishing through Alvin Buenaventura, and I believe that at least The Aviatrix came through one of his houses. What was it like doing that book?

HAVEN: It was great! Alvin's very chill, he has a keen eye, and he's a perfectionist.

The Aviatrix turned out exactly as I wanted. I was disappointed when he discontinued the line; it was pretty cool to be published with

Lisa Hanawalt,

Matt Furie, and especially

Ted May.

Injury is one of the greatest comics ever.

SPURGEON: One thing I think it's fair to say connects all of the work of yours I've seen, or at least a great deal of it, is a sense of timing that seems more in line with offbeat or even poorly done comics in the past.

HAVEN: Timing and pacing are really important. One can play with style and structure but it works best, I think, if one understands how storytelling works and how important the beats are to serving an overall effect.

SPURGEON: There's a Fletcher Hanks element to some of what you've done. Is that intentional? How important to you is pacing? How much do you work on the timing of your stories?

SPURGEON: There's a Fletcher Hanks element to some of what you've done. Is that intentional? How important to you is pacing? How much do you work on the timing of your stories?

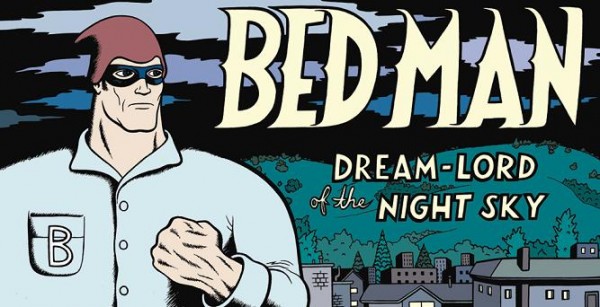

HAVEN: Yes, my "Bed Man" strip is an homage to Fletcher Hanks. I found some of his

Stardust comics on a message board one day and it blew my mind. I was thrilled when

Fantagraphics announced they'd be releasing a collection.

"Bed Man" is the result of studying the Fletcher Hanks strips and seeing how he broke down a story. I drew it in an approximation his style, but the main thing I wanted to explore was the pacing. How does he tell a story over five pages? Where are the turning points? It was very educational.

SPURGEON: Tell me about the work that ended up in UR

... Is all of this on-line work, I'm thinking maybe the "Man-Cat" stories are something I saw in print, but I'm not sure. Can you talk to me about how you conceived of this as a book, where the work itself started and even if you see this collection as having a creative cohesion?

HAVEN: UR is a collection of work that's previously appeared in anthologies and magazines. That's why the format dimensions for each story are different. I also put some of the strips on

my web site when I became paranoid that some other Eric Haven would take that domain name.

I originally conceived of this thing as a massive collection of work, spanning the last decade and a half. But Chris and I whittled it down to something more manageable. The comics contained within it were created separately and not intended to be packaged together but I think the book holds together well as a single piece. For one thing the color palette is similar throughout and for another the stories all deal with apocalyptic themes. It's about death, destruction, and ruin. But funny!

SPURGEON: Why Chris [Pitzer] and AdHouse Books? Chris tells me he was happy that you guys got along so well when he met you recently, which says to me you didn't have any sort of prior relationship. What were the virtues of what AdHouse does that made you take the book to them? Were there other suitors? What was that process like?

HAVEN: It's all because of

Rina Ayuyang, publisher of

Yam Books. Last year she conducted an art auction to benefit the Red Cross' typhoon relief effort in the Philippines. I offered an original "Race Murdock" strip and it turned out that Chris Pitzer was the high bidder -- there's rumors that a brief bidding war erupted between Chris and

Jim Rugg. [Spurgeon laughs]

Chris reached out to me after receiving the artwork and we started talking about doing a project together. We discussed several different formats before zeroing in on the final design. The entire time I was impressed with his ideas and his professionalism, but on top of that he seemed like a really nice guy. That hunch was confirmed when we met at

APE this past October.

SPURGEON: I'm not even sure why this pops into my head, but reading the

SPURGEON: I'm not even sure why this pops into my head, but reading the UR

stories it seems to me that a lot of them are pretty straight-forward thematically: they are explorations of single ideas. How do you approach the short stories from the blank page? Is there a concept, do you think in terms of the narrative and the rest takes care of itself? Is there purposeful subversion of other forms or even individual stories?

HAVEN: I start with a single image or a sequence of images that I'd like to draw and then I structure the story around that.

For example, there's a story in

UR called "The Equestrian." It started as an itch to draw something that reminded me of old Currier & Ives prints I'd see at my grandmother's house. Then I'd let my imagination take it to a really absurd place, where a demonic horseback rider is destroying everything around her, even cracking the world in half with her riding crop.

I don't know what I'm trying to do with that one. It's just me following a gut instinct to draw certain images. Maybe I'm allowing my subconscious have free reign on the drawing board. It's not completely random -- I definitely want to express a precise emotional tone to the reader -- but the mechanics of transmitting that tone are elusive.

SPURGEON: Does the violence in the story necessarily represent a cynical view of the world? I mean, do you think most things end in catastrophic violence, or is that a narrative technique for you? Would you even agree with a view of your stories that things mostly end poorly?

HAVEN: Yeah, that's my view of the world in general. I feel as if we've struggled through a very dark time in the last 15 years, starting with the election of George W. Bush. To me, the world slipped out of sync that day. Exacerbate that with 9/11, the headlong rush to jingoism, wars in foreign countries, the collapse of the economy, pending global disasters, a shriekingly apocalyptic news and entertainment media... yeah, I have a cynical world view.

But I also think that the dark stuff can be really funny. Existential dread expressed as black humor. If the timing and set-up is right, a picture of the world exploding can be hilarious.

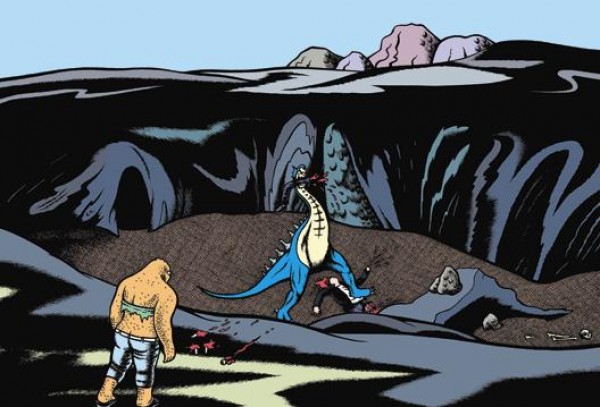

SPURGEON: Can you talk a bit about the end of

SPURGEON: Can you talk a bit about the end of Reptilica

? I found that one fascinating just in terms of its physical construction; you go from these fairly involved pages and climactic violence to this upending coda that also changes the rhythm of the story in a major way.

HAVEN: After drinking several Manhattans at a bar one evening, I stumbled into a bookstore and browsed through a hardcover collection of old newspaper comic strips. In it there was a two-page spread of

Milton Caniff's Terry and the Pirates that caught my eye and something about this sequence of strips truly affected me.

Even without reading the words the narrative was clear -- a main character was dying, apparently the love of Terry's life -- and the brushstrokes and compositions created a mood that struck a particular emotional tone. It was very effective. My heart welled up when I looked at it. But I may have been an easy target audience because I was drunk.

I was fascinated with how that feeling overtook me. Was there a way to replicate the experience? Could I draw a two-page spread that would induce that lump-in-the-throat feeling? That was the goal I set for myself, a piece intended for the oversize

Kramers Ergot 7.

I don't think I succeeded as I had wished but that's what I was trying to do with "Reptilica"... strike a certain emotional tone. Maybe people should read the comic while drunk. Maybe that's the way it works.

SPURGEON: I love the broken panel on the last page of "Bed Man." How did it occur to you to use that?

SPURGEON: I love the broken panel on the last page of "Bed Man." How did it occur to you to use that?

HAVEN: It was a way to underline the sense of falling asleep. The panel borders break away as he descends into the landscapes of his subconscious mind. I may have been inspired by

Winsor McCay's Little Sammy Sneeze, who'd blow apart the panel borders when he sneezed, but it wasn't my intent to emulate that. I just thought it'd make an effective page design.

SPURGEON: Were the "Race Murdock" strips formatted for an alt-weekly run? Was there something you wanted to say about that format, maybe?

HAVEN: The Race Murdock strips were formatted like newspaper strips: single tier, four panels. I love that format... I did a daily strip for the Syracuse University student newspaper for three years so I'm very familiar with it. But I'm now in middle age and the "Race Murdock" size constraints became almost painful. My eyes and fingers were feeling it and I needed some breathing room.

SPURGEON: I like how playful those "Race Murdock strips" are, how you slip in an out of a continuity, for example. It seems like a really strong vehicle for you, but I honestly couldn't tell -- you do them for a while, and I can see how that might become tiresome or limiting. All of your work kind of suggests this question: Could you do a extended series of stories featuring one concept, or do these comics represent everything you'd like to say and you're done when you're done? Why that restlessness?

HAVEN: I draw very slowly. It now takes me a week to draw a page on average. Because of that, I need to wrap my stories up within several pages time or run the risk of becoming bored. Long, intricate story lines might be outside my reach. Staying invested in a single protracted narrative would require me to have a sustained interest over many years. I know that's not very likely so I have to get in, do the best I can, and get out before the engine dies.

SPURGEON: This probably applies more to your career generally than it does

SPURGEON: This probably applies more to your career generally than it does UR

specifically, but why so many images of transformation?

HAVEN: I'm not sure. The act of transforming from one thing into something else is both fascinating and repulsive. You can't look at it but you can't look away either. I guess I'm interested in things that are painful and ecstatic at the same time, like birth. Or it all may stem from watching a lot of body horror movies in the 80s.

SPURGEON: As I know very little about your past, I know even less about your future plans? Is there going to be more comics work for you? Is this something you'd explore more thoroughly if it had been as rewarding as you once thought?

SPURGEON: As I know very little about your past, I know even less about your future plans? Is there going to be more comics work for you? Is this something you'd explore more thoroughly if it had been as rewarding as you once thought?

HAVEN: I can't see myself stopping drawing comics entirely. My page count may continue to fall, my eyesight may continue to deteriorate, but I do this because it makes me happy. Nothing is as rewarding to me as a completed page and a finished book. It's tremendously fulfilling.

I wish there was more money in it. I think I could do great work if I had more time and resources to devote to the craft. But the present conditions are my reality.

The current project I'm working on, not attached to any publisher at the moment, is a sword & sorcery epic. Regardless of the fear of how long it will take me I hope it'll end up being a graphic novel. I'm approaching it the same way I created the strips in

UR... following my gut, drawing whatever bubbles up from the subconscious. It's going to be wild.

SPURGEON: Your publisher suggested I ask you about your day job with Mythbusters

. Is that a good gig from which to spend your time doing something like UR? Is there a go-to story you have about working there?

HAVEN: MythBusters is a great gig for me. I've always had an interest in urban myths and I'm highly skeptical, so being able to research and produce content for the show has been creatively and intellectually fulfilling.

One benefit to working in TV is that there are frequent production hiatuses. I can sometimes get a few weeks off, even a couple months, and use the time to work on my own projects. I guess I'm doing the same thing now that I did earlier in my career: work for a while, quit work to draw, then go back to work.

It might not be the best financial decision for me to take these comic-drawing breaks but it helps to keep me sane.

*****

*

UR, Eric Haven, AdHouse Books, comic book format softcover collection, 48 pages, 9781935233305, December 2014, $14.95.

*****

* cover to the new book

* photo supplied by the cartoonist; that's him on the right

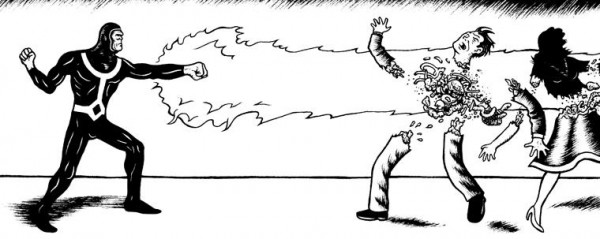

* from "Even An Android Can Dance"

* cover to an issue of

Angryman

* image from

The Aviatrix

* from "Bed Man"

* from "The Equestrian"

* from "Reptilica"

* from "Bed Man"

* transformation in "Man Cat"

* pre-transformation "Man Cat"

* one last image from

UR, this one from "The Equestrian" (below)

*****

*****

*****

posted 8:00 pm PST |

Permalink

Daily Blog Archives

November 2019

October 2019

September 2019

August 2019

July 2019

Full Archives