March 2, 2013

CR Sunday Interview: Gary Groth

CR Sunday Interview: Gary Groth

*****

I met

Gary Groth in 1994 when I went to work for him at

The Comics Journal. He was on crutches the first time we shook hands. I enjoyed working with Gary, and admire his work as a writer, an industry advocate, a critic and as a publisher with

Fantagraphics Books. A lot of what goes onto this site is a direct result of his influence. I consider him a friend of a stature that far exceeds our ability to stay in reliable contact.

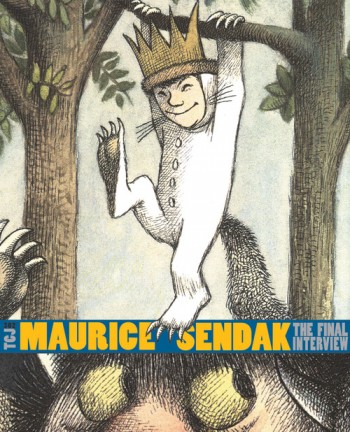

Groth is the best interviewer of comics figures and cartoonists that the medium has ever enjoyed, and one of the best in all the arts. In the new issue of his

The Comics Journal, #

302, he knocks it out of the park with a loose, funny and poignant interview with the artist and author

Maurice Sendak, since departed. I thought this might be a good time to have my own sprawling conversation with Gary: about that interview, and others, and the industry more generally. It's always great to pick his brain. -- Tom Spurgeon

*****

TOM SPURGEON: Do you worry about your generation of comics-makers getting older?

GARY GROTH: Oh, yeah.

SPURGEON: It occurs to me that up until now we've had generations of comics people that had some financial difficulty despite working during an era where comics tended to afford folks a more reliable living than what developed for many after 1980 or so.

GROTH: The underground generation in particular is old enough to worry about. You know, ironically, many of them never worked for corporations but they may be healthier in some ways than a generation that did. I'm talking about a certain level of underground cartoonist. Those that worked in a way that they became viable... after they're 40 or 50 years old they're probably in better shape.

SPURGEON: What about mainstream creators of your generation? I think many in real terms that are doing the same kind of work with the same frequency don't make as much as the previous creators just because I don't think that royalties have kept pace with inflation.

GROTH: I have some friends -- a few close friends -- in that generation in that field that I worry about. The problem is they become less productive, or fall out of favor. They have to rely on social security or selling art. I'm not sure there's a lot we can do to resolve that problem.

SPURGEON: Did you read that address that Don Rosa wrote? The retirement essay?

SPURGEON: Did you read that address that Don Rosa wrote? The retirement essay?

GROTH: I did, yes.

SPURGEON: One thing that interested me about that is he was forthright about not making as much money as people assumed he did because of the success of his work. I wonder if that's not part of something we can do, be as brutally honest as possible so that people don't extend themselves chasing a certain dream or status that then doesn't pay the way they expect it, too. I know a lot of cartoonists have cited back at me a number that Kevin Huizenga mentioned as a yearly salary in the Journal

a few years back. Can we be more honest about the exact nature of the rewards available in comics?

To put it another way, your son Conrad is about the same age as a lot of these kids that are attending comics-related degree programs at places such as CCS and SCAD. Don't we owe younger cartoonists a more honest record of the rewards given we're asking them to take on debt?

GROTH: We're asking them to learn something they can't possibly, in many cases, be able to learn. The vast majority of them will not earn a living making comics.

SPURGEON: Shouldn't we at least trash the myths of "If I get a syndicated comic or mainstream assignment or book contract, I will make it"?

GROTH: Is there still that myth? I went to CCS not too long ago. Most of the students there seemed to have a pretty good head on their shoulders. I did portfolio reviews, and I asked each student what they expected from comics, what they wanted to do. I think most of them had a pretty good understanding of their chances. Many of them talked about doing their comics as a side effort. So at least among that sample they seemed to have a good idea of what's out there, but maybe that's because James [Sturm] and the people out there make sure they know.

Wouldn't you say it's much better than it was in 1975 or 1980?

SPURGEON: I'm not sure.

GROTH: We have a situation now that reflects more the status quo of real-world publishing. If you have clout, if you have a brand, you can negotiate for a better contract. If you don't, you have to accept a lot of things in a non-ideal way. I assume a lot of people working for big companies are still wall-paid. They earn as much as those with a middle-class income. The spectrum is so broad.

I read a great piece by Francis Ford Coppola a few years ago that basically stated no one said that filmmakers had to make a living. There's no law. That seems like pretty sound insight from someone who would know.

SPURGEON: Isn't comics different, though, in that there's this major pattern of exploitation over the years? That seems to me to provide a different context than merely citing structural issues. And I don't mean just bad contracts, but an entire industry orientation that arises for a culture where your base line may be exploitative. Even the seemingly benign. You have these companies now that are capital-light, or generally resource-light, in a way that makes me wonder if that's not a basic assault at a reasonable expectation that we need to have about what roles companies play in the making of comics art. There seem to be publishers that aren't there to facilitate art or artist but themselves, the corporate identity, first and foremost.

GROTH: [laughs] Well, I'm sure that most publishers pay as little as they can get away with. There's a constant war.

SPURGEON: Let me ask that in terms of a positive. Does the history of comics exploitation and this appraisal of how tough artists can have it help foster in you as a publisher an increased vigilance in terms of how you engage with your artists?

GROTH: Absolutely. As you know, we don't do work for hire, except in some very specific cases all of the work we publish is owned by the creators, with specific rights. They fundamentally own the work. I don't know what contracts are like at a Random House or a Simon And Schuster. I imagine they arise from the nature of the individual author, and the deal, and what the agent is able to demand. Don't you think that cartoonists are in the best situation they've ever been?

SPURGEON: I think in a lot of ways it's a wash. I mean, in some ways, obviously there's way more information on the table, and people are conversant with that information, and there's even an vigorous ethos that supports certain standards, but that doesn't mean creators can always put themselves in a place to take advantage of that information. There are also counter-narratives, such as the idea that you take on a bad contract in order to one day find themselves in the position to have a better one, that can work against equitable outcomes. People sometimes choose things that aren't good for them, or good for others.

GROTH: That's the operative word, though. They choose.

SPURGEON: I guess... I would say it's more like the construction where it's not ideal, but better. I wonder if we're not a culture soaked in exploitation.

GROTH: On the other hand, there's a greater equity. There's a greater equity on the cartoonists side of things. There are more options.

SPURGEON: It is a remarkable thing, looking at the make-up of the Chicago conference last year for example, how things have improved for a lot of cartoonists that didn't have an opportunity to forge careers even 15 years ago. Joe Sacco's career I think is an amazing thing.

GROTH: But there aren't many cartoonist of his level, that can do that. We're living in a weird time. There's a shift in the underlying market realities for several classes of cartoonists. I'm not up on newspaper syndication and those cartoonists, but it's obvious that the kind of money made 50-60 years ago isn't being made by as many cartoonists now in that field. If nothing else, there are fewer newspapers.

SPURGEON: The amount of money per newspaper and what that means is definitely a factor between then and now. I'm finishing that Al Capp biography and I was stuck by how frequently a figure is cited for client newspapers where it's "let the good times roll" where today it would be like "call your social worker."

GROTH: And still there are more cartoonists out there today, more aspiring cartoonists.

SPURGEON: So does any element of that

change how you deal with the artists with whom you work? The fact there are so many of them out there and that this may have a deleterious effect on the field overall?

GROTH: No. I'm not in the business of dissuading cartoonists from being cartoonists. But whenever a younger cartoonist comes to us with a book proposal, I do explain what the realistic expectations for sales might be.

SPURGEON: Do the cartoonists share in your realistic appraisal?

GROTH: No. Almost never. Virtually every author of a book thinks it will be a best-selling book. On one level I appreciate that optimism, that idealism, but I face this grim reality every single day. I'm not infallible, but I can look at most books and come up with a pretty accurate estimate as to how it will sell. Occasionally I'm wrong.

SPURGEON: I guess that's an example of what I suggested a bit earlier about the disconnect between the information available and how that information is applied. Because you can certainly find out in rough terms what most books sell. It's just that many artists choose not to use that information to make a fair appraisal of what awaits them.

GROTH: They choose to look at the samples that are most successful. They see their book as the next

Persepolis instead of the other 99 percent of books, books that mostly don't do all that well.

SPURGEON: So is this disconnect particularly ingrained in the younger cartoonists, do you think?

GROTH: Well... that's a generalization. But it often is the case that a cartoonist without a track record will have a higher estimation of success for their work than those that have one. It's a long, hard struggle.

SPURGEON: A different question about young cartoonists: you're publishing more of them at Fantagraphics. Over the last couple of years you've announced maybe a half-dozen projects with cartoonists I think of as being in this emerging generation, cartoonists like Chuck Forsman and Noah Van Sciver. I remember even 19-20 years ago that you had to make a concerted effort to process work by cartoonists of that generation, the Megan Kelsos and the Dave Laskys, so I wondered how involved you were with these newer signings and what it was like to look at the comics made by the cartoonists coming of age now.

SPURGEON: A different question about young cartoonists: you're publishing more of them at Fantagraphics. Over the last couple of years you've announced maybe a half-dozen projects with cartoonists I think of as being in this emerging generation, cartoonists like Chuck Forsman and Noah Van Sciver. I remember even 19-20 years ago that you had to make a concerted effort to process work by cartoonists of that generation, the Megan Kelsos and the Dave Laskys, so I wondered how involved you were with these newer signings and what it was like to look at the comics made by the cartoonists coming of age now.

GROTH: It is mostly me and Eric [Reynolds] who have brought in the newer work. It's exciting. It's important to keep things vital, and aesthetically alive.

SPURGEON: Do you see strong distinctions as a group between those comics and comics that came out from young cartoonists 10-20 years ago. Or is good cartooning good cartooning in a way you see more of a continuum? Do you have difficulties processing certain things about the newer comics you're seeing. Is there any cartoonist that took you a while to come around on.

GROTH: There is, one in particular, although I can't remember who that is right this second. Okay, what you said about good cartooning being good cartooning? I think that's true, but I think that good cartooning is so much more complex than that. There are cartoonists that send work to us, and I'll love certain aspects of it. I'll love the drawing, or I admire some of the writing, but frequently the story doesn't come together. You can see strength in the components, but not in the whole. That's what we look for when we publish younger cartoonists, this sense of everything working together. I'm generalizing. I was going to say something to the effect that the stories sometimes see frivolous, but that's not really true.

I know they're learning to put together entire packages at these schools, that everyone is working on all facets of their own stuff.

SPURGEON: Tom Hart told me that he wondered if cartoonists today maybe weren't as interested in standard narratives as his generation of cartoonists. The story is not always as important as the comics delivering a certain kind of art on the page.

GROTH: I've read that, but I'm not sure I know enough to agree or disagree. We published a collection of Lilli Carré's short stories, and as virtuosic as the graphic approaches are, as she chooses different graphic techniques for different stories. Even something as obviously visually-oriented as that seems grounded in story in a way. I'm not sure I can think of a cartoonist who wasn't primarily interested in story.

SPURGEON: Basil Wolverton?

GROTH: I think that's a weakness of Wolverton's. His best work is probably based on the Bible, which of course is story-oriented.

SPURGEON: You know, I think you could argue that really strong narratives are something in two of your higher-profile recent projects, the EC reprint series and the Disney books from Floyd Gottfredson and Carl Barks.

GROTH: You don't get more story-oriented than EC Comics. Those are dense seven- and eight-page stories. If I think about whether comics require narratives, I would say they don't, but that 99 percent of the time this is what works about them, the way in which they captivate and hold our attention. That's how we interpret the world. So it's possible, but I think I've always been attracted to strong narratives. That's important to me.

SPURGEON: How close is this new issue of the Journal

to your ideal with this new, post-issue #300 iteration? Because it seems like it exists on a different progression from the last issue, but I'm not sure how you see it. Did you look at the first big-brick issue and attempt to consciously refine it?

GROTH: I'm not sure that I

consciously did that, but I'm sure I looked at #301 in some ways as I began to work on #302. I'm very happy with both issues. I was becoming increasingly displeased with the magazine. I think that's because I wasn't entirely happy with what we had to do to fill nine issues a year. The subject matter. We constantly had debates where the Journal's mission was to cover all comics or should we focus on those comics that we thought were meritorious. I was always nagged by the idea that certain comics were important to a specific subset of comics if not comics themselves. That was essentially the idea, that we could focus a magazine of more specific subject matter. I'm really happy with it so far.

SPURGEON: What would you give as an example of a feature that ran in the old iteration that wouldn't have a place in this new one? You wouldn't cover The Walking Dead

, I take it.

GROTH: You got that right. We covered a lot of mainstream stuff, and I can see certain people as important mainstream creators. I just don't see the need to do that anymore. I really wanted to do something I could feel focused on what I felt a connection to. All respect to Robert Kirkman, but I don't feel connected to his work. I wanted this new version to reflect my own attitudes, and if it couldn't do that, I couldn't see the point.

SPURGEON: Does having the on-line version give you more freedom to pursue those very specific goals?

GROTH: I think so. Dan and Tim and I are on the same page, although they have a lot of latitude. There are things I like more than others on that site, and things I'm less crazy about.

SPURGEON: One thing I think you've done well on-line is engaging the Journal's function as a kind of magazine of record. I thought the Spain Rodriguez memorials were pretty great, and couldn't really have appeared on any other site, or even in the written magazine due to the delay in publication.

GROTH: Well, we have done them there before. I don't do a lot of work with the web site, but I did set that one up and make some of the initial contacts. It might have been my suggestion.

SPURGEON: Speaking of Spain Rodriguez, do you think the underground cartoonists have received their due?

GROTH: That's such a tough question to ask. I don't know how to measure that. In some cases, cartoonists are given more than a fair shake, in other cases, less. There this whole stratification in popular art where two percent of the artists suck up almost 98 percent of the oxygen. Not just the undergrounds but generally. Crumb and Spiegelman exist in a public space that's more significant than where Spain Rodriguez lives. It's not like Crumb and Spiegelman don't deserve the attention they receive; they do. But obviously I think artists like Jack Jackson, Bill Griffith and S. Clay Wilson, I think their work could be more widely appreciated. They could have a wider readership. One of my missions as a publisher is to get work like that out there. I'm really proud of the Jack Jackson book, but it's not going to sell out. It's the nature of mass culture. Even within the niche cultures, even within this one, the hierarchies remain, and that's not always to the benefit to all of the worthy artists.

SPURGEON: You know, I always wondered to what extent you have a refined aesthetic exclusively applied to comics, or how much comics exists on a continuum for you with your estimation of prose.

GROTH: That's a good question. I'd say there's certainly a corollary between them. I don't know if I have a passion for any formal qualities in and of themselves. Every medium reaches an end having to do with the human experience. Most of the successful comics I don't think are successful because they're comics, but because of their subject matter. I think films are successful because they're films. I think people appreciate a reading experience. I don't think that's true of comics. I think

Maus is successful not because it's comics but because it's a really good work about the Holocaust.

SPURGEON: Okay, so how do you appraise someone like Jaime, where the quality of his art is an obvious factor in how his works are processed?

GROTH: Sure, but at the same time Jaime could probably do a book about gun-running and drugs and prostitution and sell more copies.

SPURGEON: And Chis Ware's formalism?

GROTH: The formalism is the subject matter.

SPURGEON: And Crumb?

GROTH: Crumb is unique.

SPURGEON: You always struck me as a guy that maybe didn't have a special connection to comics as comics.

GROTH: That's not true. I do love the form. I love the drawing. One thing I would love to do -- one thing I love about comics is the line. It's so important. I could see analyzing nothing but the line. You could blow up 30 cartoonists -- Segar, Jaime, Crane -- just blow up their line. I think that's so big of a component for the expressive nature of comics. I think everyone acknowledges this, perhaps subliminally. But probably not as much as they ought to. Not as much as they do content. But in a way, it is content.

SPURGEON: I wonder what you think of the quality of writing about comics now more generally. There's a lot of it now. When I came here, we had almost no writers. It was a weird time in that you had a generation of guys, like Darcy Sullivan and Bob Fiore, that were just not going to write as much about comics as they had previously. I remember you and I talked about the need to develop writers in the magazine, like Bart Beaty and Chris Brayshaw. One advantage of a magazine is you could have people write every month.

There's a lot more critical discourse now than there was then. It's not as hard to find writers anymore.

GROTH: There's no dearth of writers. You can't throw a fucking rock without hitting a comics critic.

SPURGEON: Are you happy with the level of discourse? Has the writing improved across the board?

GROTH: There are some good writers about comics. Probably proportionally... I mean, proportionally we were doing pretty well in

The Comics Journal. I don't know what you think.

SPURGEON: I never read it. [laughter]

GROTH: Didn't you read it when you copy-edited it?

SPURGEON: No, not really. I think it's fairly obvious when you read those issues I wasn't reading it when I copy-edited it.

GROTH: Is this the current policy at

The Comics Reporter?

SPURGEON: It's worse, because I'm pretty much the only writer.

GROTH: You don't read that, either.

SPURGEON: I prefer it that way.

GROTH: The Comics Journal was the only magazine back then, the only periodical.

SPURGEON: It was pretty much the Journal

and then there were some academic guys, like John Lent and Rusty Witek. For a quick moment or two there were a couple of competing magazines -- Indy

, Chris Staros, Destroy All Comics

, Crash

. But that was really about it. I remember jumping on some academic lists to find some writers -- I'm pretty sure that's where we found Bart. Now it's not so hard.

GROTH: There's such a volume of writing about comics that I don't really follow. I don't have the appetite. I follow the

Journal writers. Most writing about comics is consumer-oriented, reviews.

SPURGEON: Let's talk about some writing I know you like. One writer you've used in both issues of the new-format Journal

is Tim Kreider. He's a strong writer about comics, and a strong writer generally. What is it you like about him as a writer about comics? Is it just the strength of his prose?

GROTH: No, no. Tim... [pause]

SPURGEON: I can tell you what I think some of strongest qualities are.

GROTH: What are those?

SPURGEON: One is that I think he has a real honest, thorough engagement with work when he writes about it. That's something that made him perfect for the Cerebus

assignment in #301, because I don't have any doubt that he wrestled with as much of that work as possible, rather than solely thinking of an end-result essay. He's a grinder, in a sense, but more in that he takes very seriously that responsibility.

GROTH: I think that was one of my more brilliant editorial moves, assigning Tim to

Cerebus. I think that's the best piece written about

Cerebus.

Tim brings a kind of general familiarity with literature. And he's conversant enough about comics that he can apply that appropriately to comics, and render insights because of that. He's obviously a smart guy, but he has that willingness to dig into things. I'm trying to figure out a way to say that a quality of his writing is that he's non-academic. He doesn't follow trends and theories. He imposes his own sensibility, his own critical sensibility, his own idiosyncratic critical sensibility. I think that's where the best criticism comes from, as opposed to reading the application of a literary theory. I think that's where we get a more cultivated understanding of art. With a critic like that, you can learn where they're coming from and assess their reaction to the work.

SPURGEON: Is there someone that you want in the Journal

you haven't had yet?

GROTH: A writer? I can't say that there is. I can't say that there isn't someone out there that I couldn't get. I don't assiduously follow comics criticism.

SPURGEON: Do you have any response to the criticism -- I think it was Heidi MacDonald that was public with this observation -- that this latest issue lacked women writers, cartoonists and even subject matter? I know that Esther Pearl Watson was scheduled but there was a hitch there.

GROTH: Yeah, Esther was supposed to be in it. I have to admit I'm gender-blind when it comes to good writing. And to subject matter.

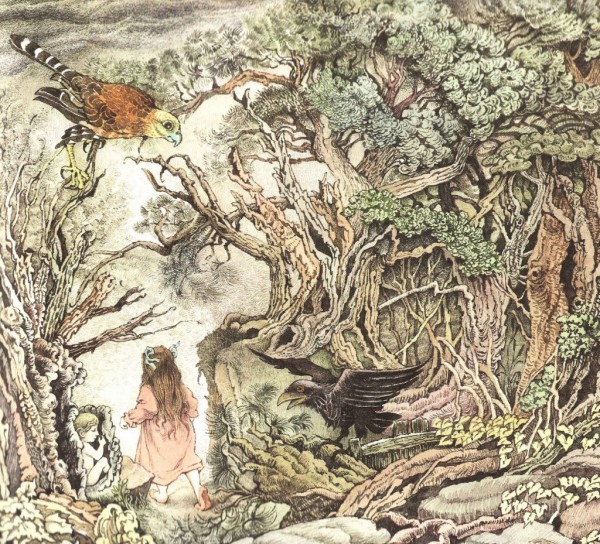

SPURGEON: One thing that you said about the Maurice Sendak interview that was interesting to me is that you didn't have a significant past relationship to his work. You had to go read up on it, which you did with great thoroughness, but it wasn't art with which you had been interacting for years and years.

SPURGEON: One thing that you said about the Maurice Sendak interview that was interesting to me is that you didn't have a significant past relationship to his work. You had to go read up on it, which you did with great thoroughness, but it wasn't art with which you had been interacting for years and years.

GROTH: I didn't read him as a kid. And I didn't read him to my kid -- I didn't tell him that part. I knew who he was, obviously. I was aware of his work.

SPURGEON: What elements of the interview are you happiest about? I'm particularly interested in why you thought it might have been a good last interview

for Sendak.

GROTH: I guess what I'm happy about -- I was worried about it. The moment I left his house I knew I had something really good or something disastrous.

SPURGEON: Kind of like this interview. [laughter]

GROTH: Yeah, right. Although, no: this could just be mediocre. [laughter]

I was concerned. After I got back, and after it was transcribed, I came around to thinking there was something deeply truthful about it. And -- however brief it was -- about our relationship. I read all the interviews I could with him before I did the interview. There was a very good interview he did that I did not read, with Terry Gross.

First of all, it was obvious he didn't want to do an interview about his career. He was somehow resistant to that. I didn't know exactly why, although now I think I know why: he just wasn't comfortable doing that. He's comfortable talking off the cuff.

SPURGEON: Now was that a function of his age?

GROTH: No, I don't think so. He

never did an interview like that. Whenever he was asked questions like that, he's spin off. He was hard to nail down. I thought there was something... he's obviously incapable of dissembling. He was able to talk about existential, difficult subjects like death. Obviously he could talk about death at the drop of a hat, but maybe I got another layer. I didn't run away from it. This was the first I'd heard that he might have been a father. He was very open about that.

SPURGEON: The interview sort of reminded me of... and I don't know exactly why, but it reminded me of the longer interview you did with Gil Kane late in his life. I thought the Sendak was similarly poignant. It struck me that they were both older men, and I wondered if you think that interviewing older cartoonists as you have so many times might naturally drive the conversations in those directions?

GROTH: That might have something to do with it. Gil was really a deeply human person. At least with me. He was the person I was closest to for many years of my life. And I have to say, that when I was with Maurice, I felt a similar rapport. You know you have friends, you have some friends with whom you talk about some things, like movies and comics, and you have some friends you talk to about more important things.

SPURGEON: Sure.

GROTH: This could be delusional on my part, but I felt that way when I left Maurice. I assumed he was going to live a few more years. He was pretty robust. We walked around his property. He was reasonably robust, and I was thinking he was going to be alive for a few years. I remember thinking this was going to be a beautiful albeit short friendship. It was shorter than I expected.

I felt that same rapport I had with Gil. Here's somebody I could talk to about a lot of things. Even when we talked about comics or film or literature or whatever, we talked about it on a certain level. Why does this mean so much to me? Why is this so good? That level. Gil and I could talk about that. Gil had a reputation for being aloof and analytical. Maybe that was true. My interview with him, we talked about his cancer.

SPURGEON: That interview had one of the most devastating things I've ever read, where Gil told a story about leaving an elevator in Las Vegas, and he realized when passed someone that he no longer had the basic connection he used to have to other human beings. That was just heartbreaking beyond words.

GROTH: I was thinking of that exactly when I was talking about Maurice a minute ago. That kind of human-level -- I'm sure Gil had told me about that previously, in conversation. He said something like that previously he had been tall and good-looking and people noticed him. And now he had to get used to the fact that people wouldn't notice him. He had to get used to the new him.

I think Maurice had that same level of honesty. He could talk about that kind of thing freely.

SPURGEON: One thing I thought interesting in that you went and looked at all of Sendak's work for this interview is that it reminded me once again for all that you've accomplished in terms of shepherding comics in a literary direction, that your conception of comics, particularly early on, was locked into a specific time and cultural place. Bob Fiore has written about the fallacy of believing, for example, that a place to make greater, more literary comics was in reforming the then-dominant mainstream expression of comics.

You also in those first few years of trying to do this were living in a time of much less access to a collective, cultural memory. So things like European comics were something you had to be exposed to when events conspired to provide you that opportunity rather than being able to simply seek that stuff out when you became curious. There was even a greater distinction back then between strip work and comic book work, that the format dictated content to a much greater, perhaps more rigid extent than the way we think of that working now.

GROTH: I think you're onto something... but I think you might be slightly off. In a way, in

The Comics Journal we were trying to expand what comics were. That's why we interviewed Jules Feiffer and Ralph Steadman.

SPURGEON: You eventually

got there.

GROTH: That was the '80s.

SPURGEON: Yeah, but you were eight, nine, ten years along when those pieces appeared. You didn't start there. Are there still things you discover about comics? Does looking at a Maurice Sendak's work change the entirety of what you think about comics in any way?

GROTH: I'm not really sure it does. Sendak was so very much his own artist.

SPURGEON: Even when you interviewed Feiffer, and you were very receptive to the fact that not only was Feiffer comics but it was comics in a way that informed comics that were being done right at that moment, there was enough of a barrier up that your choosing to say this wasn't simply understood -- it had

to be said, which is weird in and of itself.

GROTH: I saw him as a cartoonist. I see all of this as cartooning.

SPURGEON: What I wonder is if you still find people that way. Or is that not where your interests are anymore?

GROTH: I guess my interest back then was in pushing comics into a more literary mode. I wanted comics to be the equivalent of

The Bicycle Thief. In that way, I was pretty narrowly focused. Of course, my other focus was beating up on Marvel and DC [laughter] the general corporate status quo.

SPURGEON: But at that time, there really were comics that did roughly what you wanted comics to do, even if you weren't seeing them. Or they had come out.

GROTH: Do you think that's so?

SPURGEON: Did you know about the early Saul Steinberg comics? Did you look at any of Steinberg's output as comics? I don't think you were likely aware of the Monsieur Lambert

comics from Sempé -- those seem like they would qualify.

GROTH: What year was that?

SPURGEON: I think that was pretty early, Gary; certainly the Steinberg was, and the Sempé would have been mid-'60s. A couple of things from Al Hirschfeld cohere in more of a narrative sense, too. How much work of that type were you were aware of?

GROTH: That's a good question. I was certainly aware of Feiffer's work.

Tantrum came out in 1979.

SPURGEON: A very specific example that springs to mind is in the Harlan Ellison interview when you're talking about the potential of comics to have literary weight. Your example is more conjectural -- a comic that doesn't exist but has a, b, c qualities -- although you do reference a couple of works by P. Craig Russell as being in the same ballpark. But you don't say, "Like Feiffer

," and that fascinates me. I know that by that time you were certainly a big fan of Doonesbury

, but you don't naturally reference that strip, either, when talking about this conjectural model. Doonesbury

had an adult sensibility, obviously.

GROTH: That's true. I saw

Doonesbury as more of a separate thing. Good in and of itself, but not exactly the direction I wanted to push comics. I guess I saw it as a good but also restricted to a certain commercial comics mode bound by its own history. I was more interested in liberating comics for longer-form works.

SPURGEON: So when you discovered they were doing, I don't know, comics-style essays in Holiday

, from people like Ronald Searle, you don't necessarily think, "There it is." And you certainly didn't then.

GROTH: Well, that's right, that's right... but I only learned of those gradually. I would discover these obscure or anomalous comics.

SPURGEON: So is that encouraging at all, that after setting off on this decades-long journey, to find these example in comics past? That you're not just making it up as you go, or at least not totally?

GROTH: They were more like hints of what comics could be. And they weren't well-known at that time. It was like the history of film where

Citizen Kane is this obscure thing that no one saw.

SPURGEON: So when was the moment when you realized that the comics coming out were going to hit that spot for you? What comic was it that you felt reached what you had imagined for comics? When could you stop talking about comics that didn't exist yet and start talking about those that did?

GROTH: It was that whole period in the '80s, where [Art] Spiegelman was introducing us to the next generation of American cartoonists as well as to working European cartoonists, like [Joost] Swarte. That was a whole different way of looking at comics than even underground comics. Also the Hernandez Brothers. When I got the self-published

Love And Rockets, it wasn't there yet. Jaime's work was strong. When they turned in the second and third and fourth issue of

Love And Rockets, that sort of embodied what I had in my head.

SPURGEON: I know that you saw something

in Love And Rockets

. But you're telling me that pretty early on you saw not only potential but that this was the kind of comic you had been hoping for?

GROTH: Yeah.

SPURGEON: So what kind of comic would you like to see now?

GROTH: I want to see that comic I can't envision myself.

*****

*

Gary Groth on Wikipedia

*

Fantagraphics Books

*

The Comics Journal #302

*

TCJ.com

*****

* Gary Groth at Comic-Con International 2012

* art from Don Rosa

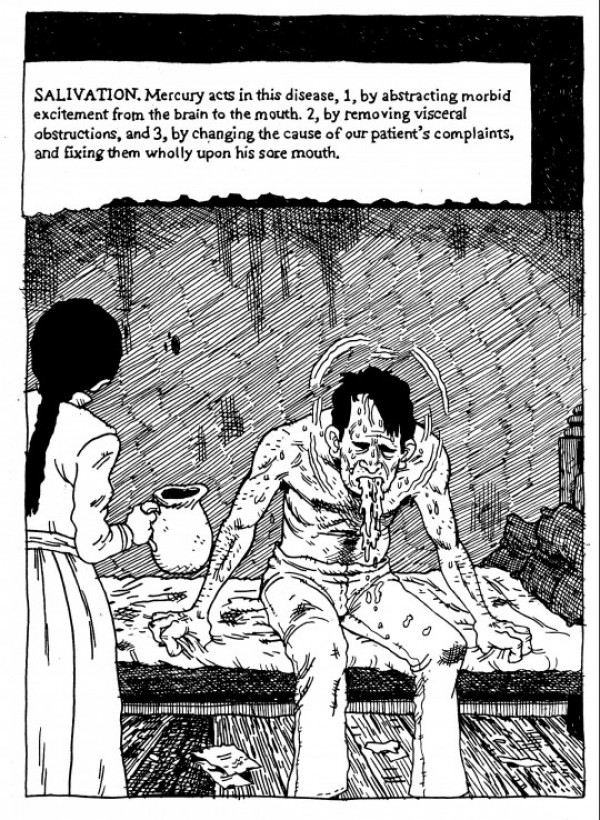

* art from a young cartoonist recently published by Fantagraphics, Noah Van Sciver

* the new print

TCJ, #302

* Maurice Sendak illustration (below)

*****

*****

*****

posted 11:30 pm PST |

Permalink

Daily Blog Archives

November 2019

October 2019

September 2019

August 2019

July 2019

Full Archives