May 13, 2012

CR Sunday Interview: Joseph Remnant

CR Sunday Interview: Joseph Remnant

*****

I didn't know much of anything about

the artist and cartoonist Joseph Remnant going into our interview, and I'm not certain I know a whole lot more about him now that our interview is done. I think his artwork is compelling, textured and assured in a way that a lot of cartoonists never quite achieve, even those working in the same visual broad strokes. I wish there were a dozen younger cartoonists like him.

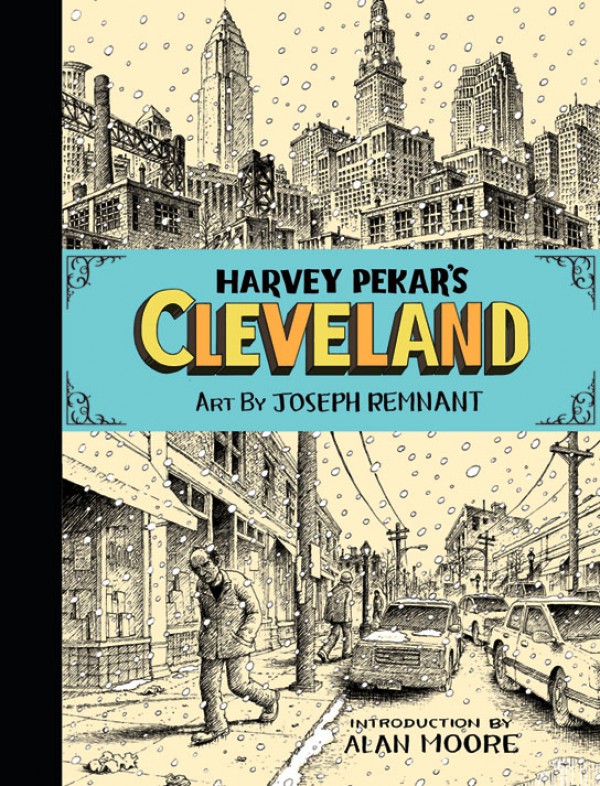

Remnant's latest is the art chores on

Harvey Pekar's Cleveland, my choice for the most pleasant surprise of the year thus far. That's a very entertaining book, straightforward and engaging, due in no small part to Remnant's ability on the page to create figures with verve and backgrounds into which one may lose oneself. I hope he's around for another 20 years, and that I get to read all the comics he makes. I'm grateful for his time with the following questions, the results of which I tweaked a tiny, tiny bit for flow. -- Tom Spurgeon

*****

TOM SPURGEON: It's my understanding that you were working on this book when Harvey Pekar passed away. What has it been like to finish that book without him? In a practical sense, were there things that you did differently that you might not have had to do if Pekar were still with us, perhaps in terms of altering bits of script or otherwise making changes?

TOM SPURGEON: It's my understanding that you were working on this book when Harvey Pekar passed away. What has it been like to finish that book without him? In a practical sense, were there things that you did differently that you might not have had to do if Pekar were still with us, perhaps in terms of altering bits of script or otherwise making changes?

JOSEPH REMNANT: Harvey passed away after I had finished about 20 pages. The script was complete, so overall, I just had to illustrate what was there. However, I do feel like his passing created a pressure to really create something special and I probably worked a bit harder than I otherwise would have to make something that I thought was my absolute best. And there were a few things that I altered that I don't think I would've done if he were alive, mainly because I think was too intimidated by him to ask if I should or not. For instance, the first and last page of the book, which are all silent panels of the city, were not in the script. I thought it added something to the way the reader entered and exited the story so I put them in. Occasionally I would break a long panel into two or other little things like that, but I don't think I ever actually altered Harvey's words.

SPURGEON: Do you think that Pekar's passing has changed the context with which the book is being received? Because it's not hard to see Cleveland

as a capping work, a graceful end note, especially given its summary, inclusive nature -- even though it's not the final Pekar book we'll see. Do you welcome the extra attention being paid to the work that way?

REMNANT: Yeah, it probably has. I suppose it reads like more of fitting swan song as opposed to just another addition to the

American Splendor catalog. I do welcome the extra attention because I think Harvey would've welcomed it. He wanted praise and attention as much as anybody else wants for their work.

SPURGEON: That last question suggests this one: what do you think Pekar's intentions were with this project generally? I can't imagine he knew it would be a posthumous one -- although I guess that's possible -- but there is a mournful tone, there, a suggestion of someone kind of making connections and drawing together a variety of smaller stories. Do you have any view on how Cleveland

might have been intended?

REMNANT: I can only guess, but I agree that it does have a mournful tone and it's a unique work in that it's sort of an overview of his whole life within the context of Cleveland. Part of me feels like he did want to make one last grand autobiographical statement while he still had the chance. Especially since most of what he had been focusing on in his later years was biographical pieces about other people and historical or journalistic comics. Another part of me thinks that Harvey was just doing what he always does; writing another story and trying to get it published so he could make some more "bread."

SPURGEON: I'm only vaguely familiar with your story, and I'm intrigued by your work in that you seem to have shown up with a fairly developed and accomplished way of making comics. Can you trace in broad strokes your comics background, what interested you enough in them to accrue the skills that you're employing now and what pushed you in this direction?

REMNANT: I didn't read comics as a kid, but I was fascinated by them because I recognized that they were made by people who made a living drawing pictures, which was something I did want to do. So I would flip through them a lot, and they certainly had some type of aesthetic appeal to me, but I just wasn't interested in the subject matter. It wasn't until my sophomore year in art school at the University of Cincinnati that, in the same year, I saw the movies

Crumb,

American Splendor, and

Ghost World. That was the first time that I realized that there was this whole other world of comics and it really hit me hard. I saw the

Crumb film first and his drawings, and the way they were represented in that movie, just blew my mind.

So I started trying to make my own comics and instantly realized how difficult it was to make a comic book. At that point, I spent about five years just practicing drawing in a very literal way. I wanted to train my mind to easily be able to draw a car or a house or a person without it being this constant, painful struggle. It's something that almost nobody does anymore, even people who are in art school, but I really wanted to have that classically trained skill. Of course it's still a struggle, but by the time I felt confident enough to start putting stuff out there, I had developed a certain amount of technique, which is what I think attracted Harvey to my work in the first place.

SPURGEON: You've mentioned that Pekar's comics are a big part of why you're doing comics, and you've expressed some aesthetic solidarity with comics like American Splendor. I think of you as a younger guy. How did you specifically access those kinds of comics, which aren't exactly everywhere you look the way they might have been, say, the early 1990s?

REMNANT: Once I found out about this stuff, I sought it out. You're right that this stuff was completely under the radar in Ohio, but because they made movies about them, you could find collections of their work. I think I bought

the American Splendor collection from Barnes and Noble and the Cincinnati Library had all of the

Complete Crumb collections, so I checked all of those out. A friend of mine actually had some

Daniel Clowes books and those were perhaps what inspired me, more than anything else, to write my own stories and put out a comic book. Those collections from

Eightball. Probably because it felt closer to my generation and it seemed like they were made by some wise ass guy that I could be friend with. In 2007 I moved to Los Angeles, which has incredible comics shops, so now I see everything as soon as it comes out and it's great.

SPURGEON: A couple more questions about

SPURGEON: A couple more questions about Harvey Pekar's Cleveland

. Was the project always intended to be split between a kind of casual history of the city and then a more specific history of Pekar's relationship with it? I wondered if you had any clue as to how that split structure developed, what Pekar intended by forming the work around two different approaches rather than a book that synthesized the approaches throughout, going more immediately back and forth between Cleveland's history and his own.

REMNANT: The best person to ask this question would be

Jonathan Vankin, who was an editor for

Vertigo, and the guy who originally started working on the script with Harvey. I really don't know, but I think the idea was to tell the history of Cleveland up until 1939, at which point Harvey becomes part of the history of Cleveland and the structure and tone of the story changes pretty drastically because it becomes much more personal. Although, Harvey didn't really indicate that he wanted there to be a page break like the way I illustrated it. He had just scrawled a line into the script that said, "Harvey Pekar and Cleveland." I suppose I chose to draw that as almost a separate title page because I wanted the reader to know that the story was changing -- that the whole book wasn't going to be this very matter of fact history of a city.

SPURGEON: Alan Moore in his introduction points out that one of Pekar's strengths was specific observation. What strikes me is that this work seems impossibly broad and ambitiously encompassing for a writer who once did an entire story about drinking a glass of water. Was it different working with this story than with some of the more specific short works you've done?

REMNANT: It was very different because the script jumps around so much, often skipping through decades at a time from panel to panel that I rarely ever got comfortable with a specific scene that I was drawing. Almost every panel required doing new research to get an idea of what that specific place and time looked like. When you're drawing a small, specific story the scene barely changes, and it's much more about capturing little expressions and subtle emotions as people interact with each other. This book required a lot more patience and research because it was so all-encompassing.

SPURGEON: One last broad question about the book's creation, and I apologize in that I'm sure it's one you get a lot: how did you approach any research involved? Were you provided with visual for the cityscapes? What about the people? Did any of your work involved visual call-backs to the way Cleveland or the people in Harvey's life were treated in other media including older issues of

SPURGEON: One last broad question about the book's creation, and I apologize in that I'm sure it's one you get a lot: how did you approach any research involved? Were you provided with visual for the cityscapes? What about the people? Did any of your work involved visual call-backs to the way Cleveland or the people in Harvey's life were treated in other media including older issues of American Splendor

?

REMNANT: I just did endless research, mostly from stuff that I found on line, but also digging through libraries and looking at movies that take place in Cleveland. I found a lot of good stuff by going through people's vacation blogs, which were actually the best because they often had very specific and high res images of Cleveland landmarks. Some stuff was very hard to find because it hasn't existed for a long time, but I was usually able to find something to work from. Of course the images were just something to work off of because in order to make something compositionally interesting, you almost always have to alter it to make it dynamic and work with the story.

I had visited Harvey in Cleveland, but not to take pictures for this book. Having grown up in Dayton, Ohio, which in many ways, is like a small version of Cleveland, I think I had a good feel of the city already. The people that I drew just walking around in the background are the way I remember people looking when I would hang out in different neighborhoods in Dayton. If it was a specific person that had been previously represented in

American Splendor, like Mr. Boats, or Toby the genuine nerd, than I would directly reference other sources. Otherwise I thought it was fine to just make it up.

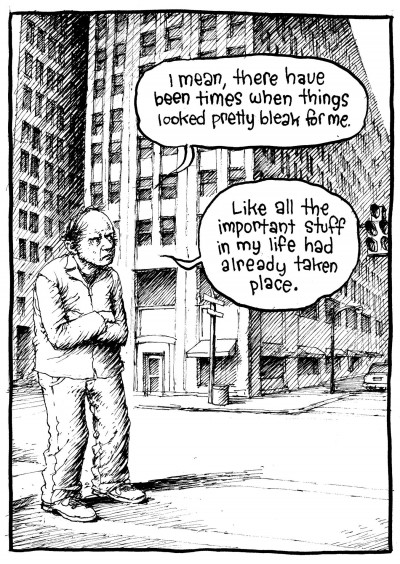

SPURGEON: Was the central image that takes over the book of Pekar walking around while talking, did that come from you or him? Is there a specific challenge visually in using that motif, for instance stopping the reader's eye from the strong left to right movement that having a representation of Pekar always walking that direction seems to encourage?

SPURGEON: Was the central image that takes over the book of Pekar walking around while talking, did that come from you or him? Is there a specific challenge visually in using that motif, for instance stopping the reader's eye from the strong left to right movement that having a representation of Pekar always walking that direction seems to encourage?

REMNANT: That was actually my idea and something that I thought of after Harvey had passed away. At first I was drawing him, like several other illustrators had done before, narrating the story in a white room with a shadow behind him. At some point I realized that that was going to get boring pretty quick and it made infinitely more sense to draw him telling the story from the streets of Cleveland, since it is after all, a story about Cleveland. That allowed me to fill the backgrounds with Cleveland landmarks and slip funny little things into the story occasionally. It also gave everything a sense of movement, which I thought was important. However, I can't really say that I thought about it much more beyond that, as you suggest I might have, other than following my own instincts on what looked good on the page as I went along.

SPURGEON: The work is told primarily with a six-figure grid, or three-tier pages, but there are several strong four-panel -- or two-tier -- pages, which as far as I can tell don't really stand in startling contrast to one another. Why four panels with some pages? Was that a pacing issue? Was that simply reflective of how much information Pekar's script wanted to convey?

SPURGEON: The work is told primarily with a six-figure grid, or three-tier pages, but there are several strong four-panel -- or two-tier -- pages, which as far as I can tell don't really stand in startling contrast to one another. Why four panels with some pages? Was that a pacing issue? Was that simply reflective of how much information Pekar's script wanted to convey?

REMNANT: Sometimes it was pacing if I felt that a certain group of panels should be lingered on a bit more, and other times it just felt that certain scenes needed more room to breath. I think because it's a book about a very specific place, it seemed appropriate to really draw attention to that visually sometimes, and really put the city scape on full display throughout the book.

SPURGEON: I'm interested in a pair of really specific design flourishes. The first is that in most cases the block of text above the visual in the panel is slightly bigger than the panel, in a way that seems to me to led a subtle primacy to the words. Was that your intention? What is it about the look of those text blocks that appeals to you?

REMNANT: I made the text box slightly larger than the image panel simply because I think it makes everything look a bit more alive on the page and not so rigid. It's the same reason that I don't use a ruler to draw out the panel borders, it just seems to make everything look a little more like one big living, breathing organism, which I like. That was my only intention.

SPURGEON: I'm also intrigued by your use of speech balloons, first of all the decision to put some words but not others in characters' mouths, the second in how the speech sometimes intrudes on the written text, but other times doesn't. Am I reading too much into how you place the speech balloons, even how you employ them, or was that a considered effect on your part?

REMNANT: The decision on how the words were separated between captions and speech balloons was all dictated by Harvey. I didn't really stray from what he put in the script. The decision to have the speech balloons break into the caption borders is the same reason I stated above about making everything seem more alive and a little more dynamic. In the instances where I didn't do that, I couldn't really tell you why. I probably should've done it all the same way, but again, I didn't really have any further intention than what I thought looked best at the time.

SPURGEON: You have a very strong illustrator's feel to your work, enough so that I think it stands in contrast to a lot of the strong comics out there right now that use cartooning basics and simplification to tell their stories. Is there anything to working with a really strong sense of image-making that you think is different than working in more simple, iconic imagery? Does making a really strong image ever get in the way of storytelling the way some people suggest it might? Do you have to pay special attention to foregrounded figures when your backgrounds are so strongly rendered?

REMNANT: I actually find this distinction to be really annoying. It just seems like such a half-baked argument to say that comics only work if they're drawn with simple and iconic imagery. There's definitely something to the idea that certain ways of drawing can interfere with the flow of a story, but I think it's much more complex than the usual arguments that you here. There are certain people who draw very simple and direct imagery, like Charles Schultz, or

Seth, and it's great, but there's plenty of people who draw in a simple style and their comics are awful. Whenever I hear people make this argument, I always think to myself, "so do you think that Robert Crumb and

Joe Sacco are terrible cartoonists?"

I think you can have as much or as little detail in a comic as you want, as long as there's a rhythm or flow to the story that carries it along, like each panel is it's own beat where the words and images work seamlessly together. Some cartoonists can pull that off while still using a lot of texture and detail and some can't. Yes, sometimes it just looks like a block of text with a static illustration next to it and those comics suck, but there are ways to still use a lot of detail without that effect. I do find that separating the figures from the background by rendering them slightly different or leaving some white space around them when they're moving helps to do that, and that's something I did in this book. I also like to use a strong light source, which is a classical, realist technique, because I like the look that everything is sort of popping out of space.

Chester Brown is a master of this and also a great example of somebody who sort of blends a realistic technique with simplified, cartoony imagery to perfect affect.

SPURGEON: Do you have a refined sense of Pekar's other collaborators, and do you look at their work for insight into your own? Do you have favorite Pekar collaborators, people that you think worked well with him?

SPURGEON: Do you have a refined sense of Pekar's other collaborators, and do you look at their work for insight into your own? Do you have favorite Pekar collaborators, people that you think worked well with him?

REMNANT: Yeah, I think I do. Again, I'll reference Crumb, Joe Sacco, and Chester Brown. These were all guys who knew how to make the story move along, and weren't just making static images to accompany the text. I think

Gerry Shamray is a great illustrator, but not necessarily for comics. But again, both Crumb and Gerry Shamray have strong illustrative styles, but Crumb was just better at making the story flow. There was a strong sense of rhythm to those strips.

SPURGEON: One thing you've mentioned in interviews is that Pekar was supportive of your work, that you didn't experience the outsized character of Pekar as much as a supportive fellow creator. Can you describe how he might have been specifically supportive of your work, what that means? Did he praise it? Did you and he talk about the work itself?

REMNANT: Whenever I would send him stuff, I would usually get a call from him in a few days and, yes, he would praise the work I was doing. He seemed exited about it. I drew this one short story for him that was never published, that was just a guy at a bank having a conversation with the bank teller, and i remember getting a call from him, and he was really shocked that I was able to capture the subtle expressions between the two people that he was looking for. Just things like that. Almost as soon as I started working with him he started talking about trying to find a book that we could do together. And he was interested in the work that I was doing on my own and encouraged me to just keep working. I really didn't have any negative experiences with him. He was eager to find good people to illustrate his work, and I think he was excited about the work we were doing together.

SPURGEON: I'm always fascinated by younger cartoonists with the displayed skill to write their own work that choose to work with writers. What do you learn about making comics working with a writer like Pekar that you might not doing your own material? I asked the cartoonist Faith Erin Hicks this question, and she responded that being able to focus on the art is its own advantage, and I wondered if you felt the same way.

REMNANT: Yeah, I never intended to illustrate other people's stories. I wanted to go the Daniel Clowes route from the beginning. Somebody else sent my work to Harvey and I got a call from him one day and I couldn't say no. He was a hero of mine, so of course I was gonna work with him. The whole thing was kind of a two-year detour from where I wanted to go, but it's a detour that I'm glad I took. There's a certain low key energy that's very similar to what it's like to live life everyday in Pekar's writing, which is something that I hope I can bring more into my own stories. He was a master at that. My favorite parts of the book are little moments like where he's helping his wife in the garden or drinking a malt shake in a department store. Some how he makes those moments very compelling, which is very hard to do. And yes, I agree that just illustrating has its advantages. It is kind of nice to focus on one thing at a time, and in the process I believe I made a big leap in my drawing ability that I can now bring to my own comics.

SPURGEON: Can you describe your working relationship with Jeff Newelt? How closely were you edited on this book?

REMNANT: Jeff mostly had the thankless task of fixing all of the typos and grammatical errors. There were a few spots where Harvey sort of repeated himself and he dropped a couple of panels here an there. Things like that that helped to story flow a little smoother. I pretty much self edited myself when it came to the visuals. When I finished the book I felt like I finally figured out how to draw Harvey so I went back and re-drew him in the first 60 pages or so. A lot of the work that Jeff did was more on the P.R. side of things. He's a great promoter of comics.

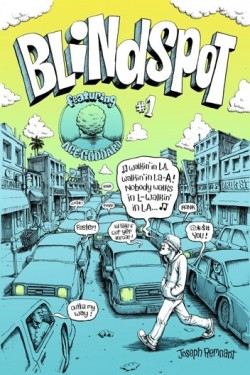

SPURGEON: I thought Blindspot was relatively overlooked, and I'm probably one of the people responsible for it being overlooked. How satisfied are you with that work? Do you plan on continuing in that vein?

SPURGEON: I thought Blindspot was relatively overlooked, and I'm probably one of the people responsible for it being overlooked. How satisfied are you with that work? Do you plan on continuing in that vein?

REMNANT: I think it was relatively overlooked because I really didn't do much to promote it and as soon as I finished it I started working on the

Cleveland book. I didn't really expect for my first self-published comic to get much attention, but it didn't help that I wasn't focusing on following it up with something and not promoting myself in the process. I'm focusing much more on that stuff now. I finished a second issue and sold out of the limited copies I printed for

MoCCA Fest, so I'm just waiting to get the next shipment to me now. I'm relatively proud of the first issue, but I can't look at it anymore. The drawing looks really crude to me. But I want to continue with it for awhile. Of course it doesn't make any money, but I love the format, and I feel like I'm just working for the future. Hopefully somebody will want to put out a collection of my short stories some day, and at the same time I've been writing a graphic novel that I really want to do, but I think I need to make more of a name for myself before I make that plunge.

SPURGEON: As someone who was introduced to a lot of readers through on-line means, what is the value of working in print comics, single-issue alt-comics even? How does that change or even enhance your desire to do comics?

REMNANT: I don't really know. I just can't seem to bring myself to become a web cartoonist. I never read web comics. I just like comics, and I think the best young cartoonists are still printing their stuff and that's the stuff that I want to read.

Noah Van Sciver is the perfect example. He just keeps cranking out those

Blammos and it's really paying off for him. I'm jealous of him.

SPURGEON: Was that your last work with Pekar? Where do you personally go from here?

REMNANT: I think it probably is. I know

Joyce [Brabner] has some stuff left that she's gonna be looking to get illustrated, but I don't know if I'm up for it anymore. Doing that book took a lot out of me. But we'll see, maybe I'll end up doing something small.

From here, I just keep drawing comics and keep putting them out there and hope for the best. That's all you can really do I guess. I suppose I'm still open to illustrating for another writer, but it would have to be a project that I was really into, and that's a pretty rare thing to come across.

*****

*

Joseph Remnant

*

Harvey Pekar's Cleveland, Harvey Pekar and Joseph Remnant, Top Shelf With Zip Comics, hardcover, 978-1-60309-091-9, 128 pages, 2012, $21.99.

*****

* cover to

Harvey Pekar's Cleveland

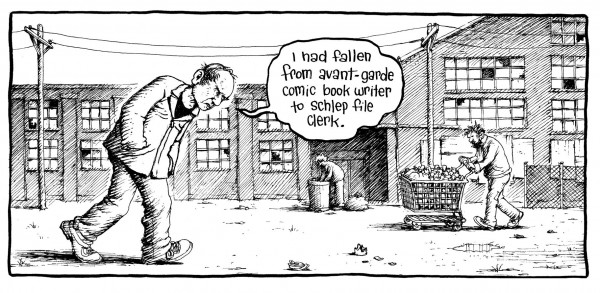

* images from the new book, hopefully placed in some sort of contextual fashion

* the one with the Letterman reference is from "Muncie, Indiana" -- an earlier Pekar/Remnant collaboration

*

Blindspot #1 cover

* an illustration by Remnant (below)

*****

*****

*****

posted 1:30 am PST |

Permalink

Daily Blog Archives

November 2019

October 2019

September 2019

August 2019

July 2019

Full Archives