June 29, 2008

CR Sunday Interview: Lynda Barry

CR Sunday Interview: Lynda Barry

*****

A lot of people were surprised when the great

Lynda Barry signed a publishing deal with

Drawn & Quarterly. They would have been fairly astonished to learn that Barry wasn't moving from one kind of a deal to another; she says she didn't have a publishing deal of any kind before Chris Oliveros' alt-comics anchor company stepped in. One of the great veterans of alt-weekly publication with her

Ernie Pook's Comeek, now seen by most people on-line, Barry slipped back into comics culture's consciousness this last decade with some audacious book work and as an item of discussion when it came to suggesting female cartoonists that might have cracked a reasonable but re-curated

Masters of American Comics exhibit. Her new book,

What It Is, is the most consistently lovely-looking thing she's ever made, and its dissection of the creative process reads, well, a lot like a comics version of this interview, if only in tone. I greatly enjoyed our back and forth. -- Tom Spurgeon

*****

TOM SPURGEON: The announcement that you were working with Drawn & Quarterly took a lot of people by surprise, because the trend's been overwhelmingly in the direction of artists moving from comics specialty publishers to more general book publishers. Can you talk a little bit about how that deal came together and what appealed to you about working with that particular publisher?

LYNDA BARRY: Well, in my situation, until Drawn & Quarterly came along, I couldn't find a publisher who was interested in my work at all. There was no one.

I'd been working with a small publisher in Seattle called

Sasquatch, but after

One Hundred Demons, they didn't want any other books from me.

I'd always planned to do a sister book to

One Hundred Demons that was about the writing process, and always intended to do it with them. When I pitched it to them, they said no, and no to any other books of comics. The End. That was it.

I never understood why, exactly, because I think

One Hundred Demons did OK for them, sales-wise, and I believe my other books have done fine too. So it made me feel pretty bad.

The same thing happened with

Cruddy. After it was printed,

Simon & Schuster wasn't interested in another novel from me. But in that situation my original editor left and I didn't know anyone else there, and it was a little bit more understandable.

So really, there was a long period where no one wanted to print my work at all. When Drawn & Quarterly asked me, I was overjoyed, because I love making books, and I really wanted to do

What it Is, and I was happy someone cared about my work enough to want to print it. And I've always loved the Drawn & Quarterly books, they are so beautifully done. It happened that I was half way done with

What It Is when D&Q contacted me. I had just decided to do the book anyway, not knowing if it would ever be published and in a way not caring anymore. I just wanted to give the thing form.

I suspect it was

Chris Ware who may have spoken to D&Q about me. I think he contacted some people and helped me out. He's been good to me and I suspect many other cartoonists in this way. I love him for it. I thought the publishing side of my career was pretty much over.

I was at a pretty low point because I was also getting kicked out of news papers left and right, I've gone from being in over 70 papers to being in 7 papers. I was scrambling to find a way to keep working. My solution was to start selling original art on eBay. I just said, 'to hell with it!' and opened a version of my own hotdog stand on eBay and started selling pictures and it's one of the best decisions I've made because I can still support myself, though it's still a struggle.

The other way I was able to make some money was by teaching writing workshops, and it was teaching that really helped shape What It Is. It turns out I love to make pictures and I love to teach, so even if I couldn't get published or keep my comic strip going in newspapers I found a way to keep going.

By the way, working with D&Q has been by far the best publishing experience I've ever had. I feel like a won a prize.

SPURGEON: I don't want to spend a lot of time on what sounds like a horrifying experience, but there's very little known about the alt-weekly and weekly newspaper comics market. What do you think happened that you lost so many clients as you just mentioned? Was it a matter of you specifically losing clients, or was it your being replaced by a certain type of feature, was it those papers dropping comics...? Were you hearing from the art directors as to why? For that matter, when did you start to notice the decline and how quickly did it happen?

SPURGEON: I don't want to spend a lot of time on what sounds like a horrifying experience, but there's very little known about the alt-weekly and weekly newspaper comics market. What do you think happened that you lost so many clients as you just mentioned? Was it a matter of you specifically losing clients, or was it your being replaced by a certain type of feature, was it those papers dropping comics...? Were you hearing from the art directors as to why? For that matter, when did you start to notice the decline and how quickly did it happen?

BARRY: When I was first out of college in 1978 when hippie traces were still in the air, and "underground" newspapers were becoming "alternative" newspapers, and the same thing happened to comics. Little papers were springing up in different cities and there were easy open ways for cartoonists to get their work printed as long as money was not an issue. They were called "New Wave" comics for awhile too but then went back to "alternative."

So after college I moved back to Seattle and I just happened to live a couple of blocks from the

Seattle Sun, which was our city's alternative paper, and I brought my weird-ass comic strip in to them.

The woman I showed it to hated it so much she actually started yelling at me. She said my comics were racist against Mexicans. I remember being stunned and looking at her and thinking, "What the fuck are you talking about, sister?"

The strips I brought in were about women and cactuses. The strips were about women in bars meeting cute interesting cactuses and trying to decide if they should sleep with them or not. If there was a way to make it work. They were called

Spinal Comics. I had just gone through a bad break up and guys seemed like cactuses to me, so I drew cactuses. I could not see where she was getting the Mexican angle at all.

But I'm sitting there she is certain they are Mexicans and so she is giving it to me loud enough to attract the attention of a guy who is sitting at another desk who it turns out hated her. Really hated her.

He follows me out as I'm leaving and tells me he'll print my comics. Turns out he ran the back page of the paper and printed my strip there just to piss her off. And thus my career came into being.

I think I got $5 a comic strip. I wish I could tell you the pay is much better these days. One of the papers I got kicked out in the last few years was in Philadelphia. I was in that paper for over 15 years. I got $15 a week and that never changed.

At the same time my strip was printed in the

Seattle Sun,

Matt Groening, who was a friend and the former editor of our college paper where my strips were first printed, moved to LA, got a job in a copy shop, and started a little comic book called

Life in Hell which he sneak-Xeroxed. It was about his experiences living LA and drawn mostly to just send around in letters. I remember the first one had all these police helicopters on the cover and that blew my mind, to think a friend of mine was living where police helicopters chasing people woke him up at night. We wrote a lot of letters in those days when long distance calls were impossibly expensive.

He got a job at the

LA Reader, another alternative paper, and he wrote the most incredible column on music. I still have hopes that those pieces will be re-printed someday. They were hilarious and brilliant. He wrote about my comic strip in one of them. My comic strip had gone from being about cactus to being about kids, and he wrote about it and because a network of alternative newspapers was forming, the article reached Bob Roth at the

Chicago Reader who called me in Seattle and asked me to be part of his paper. That was nearly 30 years ago. They paid $80 a week for a comic strip. That was unheard of. I could live off of that!! I'd like to add that I'm still getting $80 a week and I still am grateful for it. Once my strip was in the

Chicago Reader, other papers saw it and contacted me. I wish they could have paid $80 too, but mostly it was $15 and $20 a week and in very lucky circumstances $25 or $30 a week. This is still the standard rate of pay. At least it was for me.

Matt's strip began to run in the

LA Reader and he lobbied for my strip to be printed there too, and it was. He has always been a genie for me, that guy.

Part of what has happened to alternative newspapers is that they have been either been purchased by a bigger company like

The Village Voice,

New Times, or Creative Loafing which just purchased the

Chicago Reader, or they have been run out of business by a larger competitor with non-local backing. One of the first things that happens is that the cartoonists are kicked out. Not all cartoonists, but my comic is often axed the minute the sale is complete. And I can understand why. The paper's aren't as alternative or freaky as they once were, and having a comic strip in the paper that is often weird and sad just leaves editors with question marks over their heads. There was a time when it wasn't that strange, but now it is strange to have that kind of strip in a paper.

I can dig the situation! I get it. I'm not torn up about it at all. And I'm happy that D&Q runs my weekly strip and the strip is also on a myspace page run by a friend of mine who helps me organize my writing workshops, and they are posted at the great

Marlys Magazine website out of Australia, so the strip lives on. It's just that now I have to support it instead of it supporting me, but I'm good with it. I know how lucky I was to have so many years of being in print. So much of it was pure luck.

Just the same, every time I get the dreaded e-mail from a paper I've been in for 25 years I'm always sad. For the most part it's because a paper has been sold. But it could also be because my strip just really sucks now and I just can't tell.

SPURGEON: Let me ask you about that. You've been doing the strip for so long, do you have any conception at all on the quality of your work over that time period and particularly any fluctuations in that quality? Is there a period you're happier with than others, or strips that you like more than perhaps you think your readers might? Are you really too close to tell which work might be of a greater quality than other work even when some time passes since your creation of the work in question? If so, is that a matter of being too close or choosing not to look at the work in that way?

SPURGEON: Let me ask you about that. You've been doing the strip for so long, do you have any conception at all on the quality of your work over that time period and particularly any fluctuations in that quality? Is there a period you're happier with than others, or strips that you like more than perhaps you think your readers might? Are you really too close to tell which work might be of a greater quality than other work even when some time passes since your creation of the work in question? If so, is that a matter of being too close or choosing not to look at the work in that way?

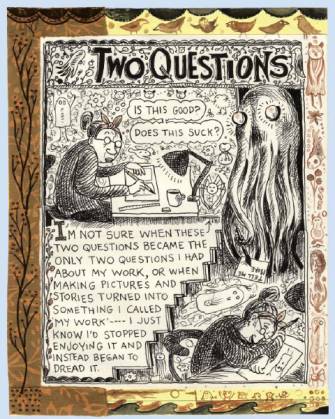

BARRY: I try really hard not to think about my comic strip unless I'm doing it. I try hard not to know what people think about it, if they like it or hate it, because it throws me off whatever the thing is that helps me make the strip.

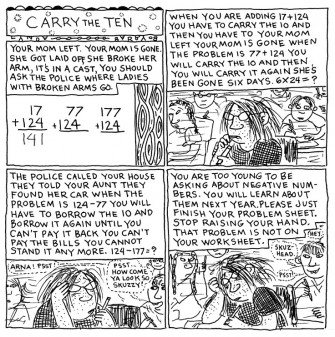

There is a specific feeling, a state of mind that happens when the strip starts to roll. I did one this morning and I could feel the thing just start to move the way a dream has its own movement. I had no idea what the strip was going to be about, or where it was going at all, but if I get into that state of mind I don't have to worry about it, really.

The strip I did today was a continuation of last week's strip. I didn't know it was going to be that when I started. All I do is I start measuring and drawing the panels, I start to ink the panel edges -- today with a pen, though I usually use a brush; more on that later -- and as I'm inking the panels I usually hear a line in my head. It is different than thinking. It's like I actually hear it spoken. It's not magic, not any more magical than when we hear people in our dreams speak to us. I had people yelling at me in my dream last night. They were really yelling and I was really upset by it, I woke up and I was shaking, but I never thought the people in my dream were real. They caused real sensations in my body, but they weren't real in the way you and I are real.

When I work on a comic strip, and I hear the first line, it's that kind of realness, the realness that causes physical sensation.

One of the reasons I make comic strips is to be able to experience that. I believe it's the same thing that happens to kids when they are in deep play. There is an "elsewhere" I get to be when I work.

I've attached the two strips. They were written with no penciling, pre-meditation or corrections apart from one letter I had to white out in the first strip. Are they any good? Well I don't know the answer to that at all. But while I was writing them I had the state of mind I aim toward, and it's a state of mind that seems to have an urge to make a story. I think it's a basic human ability. It's the thing I work toward helping people get to when I teach my writing class. I've found that anyone can do it. Anyone.

The only thing about it is you have to be willing to accept the story that comes, sad or funny, soothing or upsetting. That's the one law I have to follow when I work. I do think it means I have no ability to assess the quality of the work or what it means to others, except when that state of mind won't come. Because sometimes it won't come at all. And there have been times that it has happened for months at a time and I've been convinced I'll have to give up the strip. It comes back. Then it leaves again. And I think this is the way of things in the image world.

Flannery O'Conner said that it was as crazy to think your faith will always be with you as it is to think your loss of faith will always be with you.

Right now I'm organizing 30 years worth of comic strips for the D&Q reprints and whenever I find those strips which were written with the thinking part of my head rather than that odd image making place in my mind, those are the ones I want to throw away.

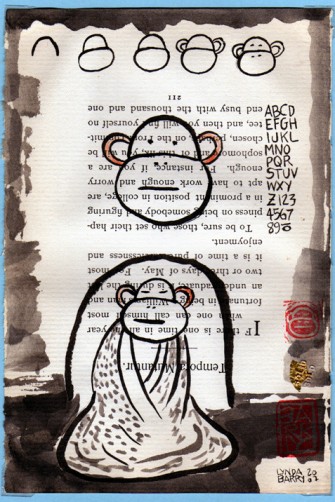

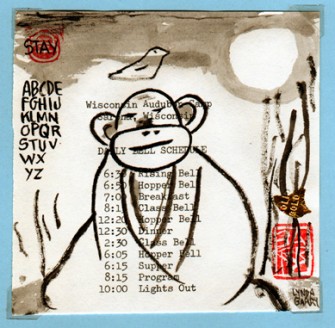

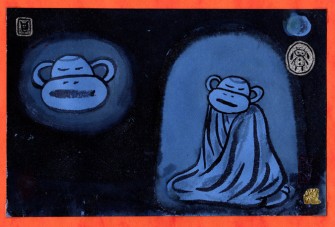

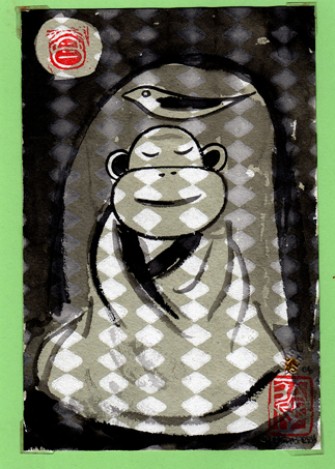

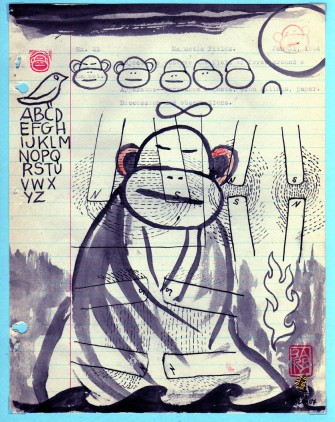

My drawing is another thing, though. When I'm in a bad state of mind, like I am now because our home is threatened, my drawing really suffers and I find it hard to control a paintbrush. Thus the pen work these last weeks. I don't have the steadiness to support brush work right now. In the evenings I try to work on it by drawing monkeys in meditation. I attach some of these below. I've drawn a couple thousand of them, and I suppose it's the closest thing in my life to prayer besides when I write or say the alphabet.

I started drawing the monkeys after a friend of mine died and I was so devastated I really couldn't do a thing. Then I found I could paint monkeys. I thought I would paint 100 of them to just help me calm down, but when I got to 100 I found it wasn't enough. That was three years ago. The other night when I couldn't sleep I painted 25 of them in a row. So I lean on my work and I know without it I'm lost, and this is the reason I do my best to keep myself from knowing too much about what people think about it. I need it too badly to put it at risk and wondering what other people think puts it at risk.

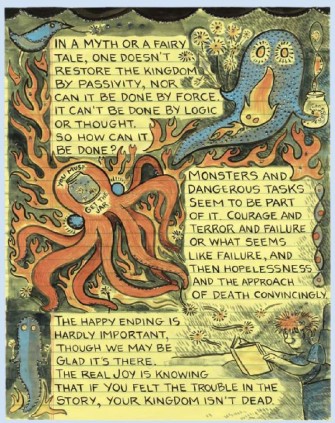

SPURGEON: This takes into some of the issues raised in your book, then. Can I assume when you say there are strips that don't have the quality you seek that you've dropped from forthcoming collection that there was a process for you in realizing what things you valued about your work? Is it possible that process is ongoing, and that if you were to collect material 10 years from now there are different strips in which you might not be interested because of qualities they did or didn't have that's not a concern right now, or do you feel you're arrived at a set of value regarding the making of art that you'll carry with you from now on?

SPURGEON: This takes into some of the issues raised in your book, then. Can I assume when you say there are strips that don't have the quality you seek that you've dropped from forthcoming collection that there was a process for you in realizing what things you valued about your work? Is it possible that process is ongoing, and that if you were to collect material 10 years from now there are different strips in which you might not be interested because of qualities they did or didn't have that's not a concern right now, or do you feel you're arrived at a set of value regarding the making of art that you'll carry with you from now on?

BARRY: I'm not going to drop anything from the collection that's been printed already. There are strips I want to toss, certainly! But if it's been collected already or printed all ready, I'll include it.

SPURGEON: To re-direct the question a bit, I'm wondering about the effect that this exploration of the creative process has had on your own creativity. Unlike a lot of creative people who explore these areas, you have an ongoing gig. Is there anything different in your work now having undergone this process of self-discovery? Are there differences in the work itself, or your attitude towards it, or maybe simply hitting a certain kind of mark more frequently? Or this is the kind of thing whose effects can't be constructed in that manner?

BARRY: I didn't realize until you asked this question that my approach to making images about the creative process is exactly like my approach to making a comic strip or writing a novel. It's not something I separated from myself in the way I may separate myself from a subject I am researching and writing a paper on.

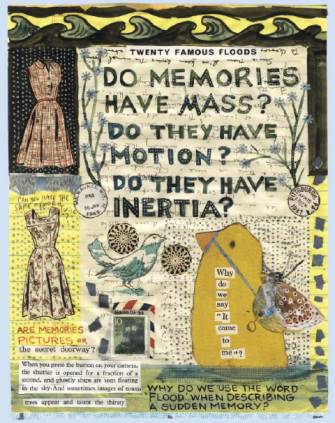

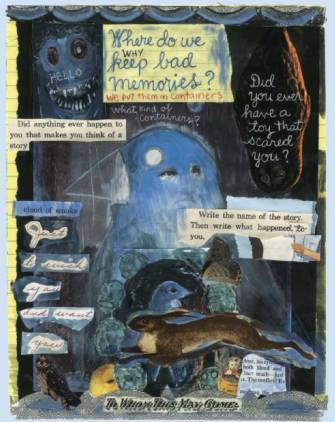

If my subject for a book had been "sleep," I probably would have done it the same way, by just sitting down and making images about sleep, and because of this activity, anytime the word "sleep" came up in my day via media or conversation or even research, it would stand out in a way that would make me take notice and automatically be knitted into the fabric of whatever it is that helps me make my images. The word "sleep" would have me follow it whenever it came up. This is different than me hunting it down with a purpose in mind.

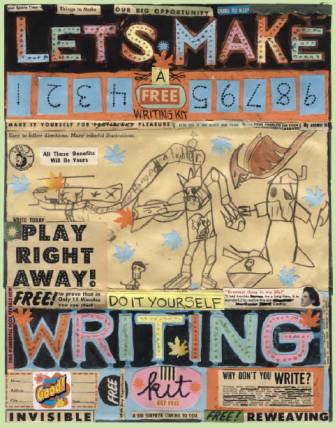

It's the exact opposite of thinking of something first, then researching it, then writing it. While making What It Is, it seemed that the actual physical act of cutting things out and gluing them down, or of using my paintbrush -- that actual physical act was the thing that generated the content. The pages I made never felt like an illustration of an idea, but rather an unplanned result of the experience of an idea.

So if anything of making What It Is has affected my creative process it is the rediscovery of what I knew as a kid: It's the physical activity of making something which leads to its meaning and purpose, and not the other way around.

As to hitting the mark more often with my work, I don't know if I'm any better at it from an objective point of view. Subjectively I can say I enjoy it more than I ever have. Part of that is due to working for the most part in isolation and part of it is from teaching. My students inspire me to be as brave and spontaneous as they are. In my classes no one is allowed to say a word about any of the work we read out loud, and I ask my students not to read over anything they have written for at least 48 hours. Not having a real idea of what other people think of me or my work and not having a real idea of what I even think about my work has been a big advantage. It allows things to happen that wouldn't otherwise have a chance to exist long enough to become an experience.

In this way work becomes more of a practice than a means of production.

SPURGEON: I reached out to a few comics-interested people before starting on this interview, and the one thing all of them were curious about was this really lovely style that you've developed that you utilize in What It Is

, a style that stands in great contrast to most of the work of yours we've seen. You can see some of it in One Hundred Demons

, but the presentation in What It Is

seems more formally ambitious, really. Can you talk about how this style came to fruition, maybe why that style for this book?

BARRY: Well, I've always loved collage and along with the work I do that people see there is a lot of work no one sees. Except for maybe my husband, no one has seen the collages I've done over the years and why should they have? I make them for no real reason, mainly to be making them the way you go for a walk in order to walk, not to have a walk you can show someone afterward. For some reason collage has always been a huge help to me. I've always liked mixing collage and painting.

What It Is started happening when I realized I might never find a publisher who would print my work again, understanding that it was a real possibility, and there was something about this that made me able to just start making the book anyway, just the way I wanted to. I actually didn't think anyone would ever print it but I liked making it. I also finally relaxed about the fact that I like to work on legal paper, or trash paper, phone books, falling apart dictionaries, any kind of paper that isn't actual art paper. I can make comics on legal paper with no hesitation. Art paper still causes me to freeze up. All I can think about is how much it costs. I have paper I've been dragging around for 20 years because I'm not good enough to work on it yet. I know this is insane but it's true for me. I can't work on expensive paper just like I can't really stand to wear expensive clothes or shoes. I just know I'm going to mess them up.

When I was making the pages for

What it Is, I just didn't have any reason not to do it the way it came to me, because there was no one waiting for it, no one who had an opinion about it, and most importantly, no one who would lose money on it. When someone might lose money on something I'm working on, it's not all that fun to work. I'd really rather not.

So there was no planning at all with this book. About halfway through I found out D&Q wanted to reprint my old work and I asked if they would consider the book I was working on. I didn't think they would but they did. And once I knew how many long the book would be, I could finish it. It's always much easier for me to make a book if I have the size and page count first. Maybe it's like doing a four panel comic strip. I know how long it's going to be and that creates the structure. Knowing D&Q was publishing it made me bolder in a way because they do such beautiful reproduction and they are so incredibly open-minded. That's a pretty dreamy combination.

SPURGEON: Has the ease of that working relationship made possible other projects? You mentioned that you like to know a page count; does having a supportive publisher work allow you conceive of future work in a similar way?

SPURGEON: Has the ease of that working relationship made possible other projects? You mentioned that you like to know a page count; does having a supportive publisher work allow you conceive of future work in a similar way?

BARRY: For me, page count actually makes a project take shape. Before I connected with D&Q I was thinking What It Is would be about 225 pages long, because it would be about the same page count as

One Hundred Demons, and I needed that kind of limitation.

I wonder this necessity for a page count or panel count is because of my work with

Marilyn Frasca at

The Evergreen State College. She wanted us to work in series, and as I believe I mentioned, we had to do 10 finished paintings a week to stay in the class (or drawings, or sculptures) plus write a minimum of five pages a day. Having that kind of template allows the work to happen in a way that has a beginning middle and end in terms of producing it. I could tell how much work I had to do and I could tell when I was finished. Just those two things are a big help.

When I teach and I give my writing class a word to work from, like "teeth," I ask them to write down the first 10 memories that come to mind having to do with that word.

But they number the page first before they know what the word is, and they know that once I say the word, they will only have three minutes to complete the list. Only then do I give them the word. My experience is that limitation is a real help to imagination and memory.

Having a supportive publisher is incredible. Chris Oliveros is not just supportive, he's actually reliably helpful. After working with him for awhile I realized I really could leave certain decisions up to him with confidence. I don't know that I've ever had that before with an editor/publisher except Jennifer Sweeney at

Salon. Both of them wanted what my work is made of, they never tried to make it more understandable to people, or more mainstream. Working with them felt like having someone who could tell which way I was trying to guide my horses and they did what they could to clear the path for me.

I've had the opposite experience with editors. I've had an editor who told me my work was dumb, another who said it was remedial, both of them telling me this in the final stages of production of the book I was working on. I've had editors who never read the book at all before it went to press, ones who wrote a synopsis of the book for the publisher's catalog mentioning characters and events that weren't in the book, and one who told me the reason I needed to come to the American Bookseller's Association event was because there were authors that were "younger, prettier, and thinner" than I was, and book buyers needed to have a reason to select my book. I told him it was probably a bad idea for me to come because they'd see I was old, ugly and fat, and that would probably put off sales.

I wish I were making this up.

For the most part, it wasn't malice on the part of these editors that made them say these things, just extreme overwork and carelessness. But there were one or two situations I couldn't excuse. I've worked alongside other editors and have seen things they do up close which shocked me. Mean and dismissive comments about the work we were supposed to be editing really caught me off guard. Maybe it's what editors do, but I wasn't prepared for it. For me, anyone who takes a pen or a brush to a page should get all the support and help I can give them. I owe my happiness on this earth to people who make things. It's hard for me to understand how editors can be so harsh, but some are, and they have no hesitation about it. The wildest thing I've ever seen, and I've seen it often, are editors who begin editing a piece before they've even read the entire thing. I can't understand that at all. If you don't know what you're editing, and how could you unless you've read it first, what kind of editor are you? A bad one, I'd say. But the thought that we should read something through once and better yet twice before we start to help with an edit is something most editors won't even consider. Again, this may be due to deadlines and overwork, but it's still a lot like the judging on

American Idol. One shot, and if I'm in a bad mood, and your work looks bad to me because of that bad mood, tough luck for you. Next!

A good editor is someone who does more than fix up or limit your work. A good editor is someone who gives you an even bigger playfield than you would have if you were on your own and is ready for and receptive to the unpredictable transformations that can happen when things are going right.

That's a long way of saying I owe both Jennifer Sweeney and Chris Oliveros a great deal. They've both given me a huge playfield and made my work better than it would have been without them.

SPURGEON: Do you think the problems with editors and even publishers you've just described have had anything to do with the unique nature of the comics medium? Do the people you've worked with in the past dealt with comics differently, or have you found more similarities than differences?

BARRY: I've always felt funny about my comics being edited, probably because the writing and the drawing come at the same time for me and it's odd to have someone else reaching in to try and change one little part. The troubles I've had with editors and publishers are probably pretty typical. I've heard the same stories from other cartoonists and writers. The minute money comes into the picture, the right to edit the work comes into the picture too.

If I'm doing something just for the money, I don't argue with editors at all. If they want to change things around in a way that makes no sense to me, I'm happy to do it, because bills must be paid! I don't take on this kind of work unless I really have to, but lately I've had to, and I've felt lucky to have some jobs come my way.

But they really are just jobs to me. I understand the editor is my boss, and I understand my goal to make my boss happy. Sometimes a boss digs my work completely and I have a very good time working on the project. Sometimes a boss is insane and wants to direct every square inch of the page, and I've learned to just roll with that, especially because those bosses never notice I don't put my name on the work. There may be a wee illustration credit on the side of the page that someone in production might remember to put in, but for the most part I can be pretty much invisible. People who know my style may recognize it, but my name won't be there. The craziest bosses never ever notice this.

I've only had to work for a few totally insane bosses, but there have been many partially insane bosses. One of the most insane bosses I had insisted that I had to include quote marks in every dialog balloon, because it was someone speaking and the style sheet at their publication required quote marks around text to indicate speech. I tried to explain that a dialog balloon indicates speech on its own, so quote marks weren't necessary, and he went nuts, telling me he knew what he was doing, so I put them in. Then during the production stage they had to take them out because his boss saw them and couldn't understand why they were there. I got blamed. I didn't care. I cashed the check. I paid my bills. I never took a job from that guy again.

I'm a lot more easy-going with this sort of thing than I used to be. Probably because it's clear to me that those kind of jobs aren't my actual work. It feels completely different to me, so I'm not as attached.

If the work is my own, I'm not happy being edited at all. I've gotten much less easy-going about that as I've gotten older. Sometimes a suggestion may be good and when that happens, I'm delighted to give it a try. But if it isn't a good suggestion and if an editor insists on me changing something, we will have a big problem. Like a mongoose-versus-a-rattlesnake-in-a-laundry-basket type of problem.

SPURGEON: Lynda, I wanted to ask you a question or two about processes that you describe in What It Is. One thing I couldn't quite understand is a few places where you seemed to be suggesting that the participant try to have a better grasp on how much time had passed or how much time one spent doing something. What is the value of being aware of time in that way?

BARRY: Actually that may be the most important part of the whole process. Limiting the amount of time one works on something seems to create a structure on its own.

When I teach, my students don't write for longer than eight minutes at a time. There is a lot of preparation before that eight minutes, but the actual writing of the piece only lasts for eight minutes and all I ask my students to do is keep their pen moving in one way or another for the whole eight minutes, either by writing the story as it comes, or by just writing the alphabet when the story stalls.

After five minutes I tell them they have three minutes left, then one minute left. The stories seem to structure themselves within this time frame. They have a clear and natural beginning, middle and end. Awareness of time is something like the measured beats in a short piece of music. It's an awareness you can actually forget about while you are in the experience. It's a bit paradoxical in that way, an awareness of time that allows you to forget about time. Sort of like when we took recess as kids, forget until the warning bell, then wrap up what you're doing and be back to class by the final bell.

I've always been curious about how our experience of time varies. If you've ever been in a car wreck maybe you've experienced the near-hallucinogenic slow down of events. Almost like a moment can accordion out and you can be very much inside the tiniest parts of it. And if you've ever fallen in love, you've also experienced how six hours can feel like a single hour. Or the reverse, during heartbreak, an hour can feel like six hours. I don't believe our experience of time is a steady experience. There is extreme fluctuation all through the day. That's the thing I'm trying to get people to notice, because it's helpful to know there are eight-minute periods where so much can happen and eight-minute periods where nearly nothing can happen. If you like basketball or hockey you've seen those players be able to move in the spaces between the seconds on the countdown clock. When I watched the Bulls play during Michael Jordan days, I was always aware that he was having a completely different experience of the same 20 seconds we were simultaneously living through.

Writing by hand for a limited amount of time seems to work much better than writing for an unlimited amount of time on a computer. The delete button and no limitation are the two things can stop experience and give it too much drag-weight to move though time gracefully. These two things allow you to "fix" something that doesn't even exist yet. We're editing the experience before we even have the experience. It's madness but it's something most of us now do without question. We believe it's the way to write. Even as I type these words I find myself going back and editing sentences before they are even finished. The delete button is irresistible. And also the speed of typing is irresistible as is the "finished" look of typewritten words. Who wants to give up the ability to take every action back? It's a recent kind of super power we don't have anywhere else in our lives.

Handwriting seems much too slow to those who use computers but I believe the slowest way is the fastest way, and I believe there are invisible advantages to moving your hand while drawing letters on actual paper in terms of pulling the back-of-the-mind action forward and onto the page. Handwriting is a physical act that reminds me of ice skating. There is momentum and travel across space, leaps between words, and a trail that is left behind which isn't as important as what happened during the skate. No ice skater learns to skate by looking back at the lines left on the ice. It's the actual doing that both puts the experience in us, and brings it out of us.

Actually I learned a great deal about handwriting by watching ice skaters, especially handwriting with a brush, which seems like the slowest possible way to work but for me at least, is much faster and goes deeper than typing a story. I believe there are a lot of stories which can't be written on a computer. They come from the hand itself. Later they can be transferred to a computer, but in the beginning there is a huge advantage to writing by hand.

Typing is ideal for a lot of things, but I'm not so sure it's that good for the initial stages of making a story. I don't think an unlimited amount of time is good for making a story either.

SPURGEON: Your mention of different experiences of time makes me think of how we experience art in general, or directly how it might relate to this work, which is very different than the bulk of material that comes out these days. Do you have any idea how this work will be received? Does that enter in your thought process at all? Do you have hopes that it will be received in a specific way, or a specific effect it might have on people? Do you have suspicions?

BARRY: The thing I hope What It Is will do is make people itch to make something. I'd like it to make them want to make something so much that they don't feel worried about what it will be for first. That's what I think stops a lot of people. They want to make something but even before it exists they feel they need to know what purpose it will serve. And if they don't know what purpose it will serve, often that is reason enough not to make it. So they stop themselves before they even get a chance to try. I like to think this might make them skip that part and just make something— but who knows?

But I do feel a bit hopeful. I think it may from the reactions I've gotten from those who happened to see parts of the book while I was working on it. I started to feel especially hopeful when different teenagers and kids who came by my studio saw it and all of them instantly wanted to make something. I think there is something comforting about what a mess the book seems to be, and how hand-done it is, and how it's made mostly of trash, just glued-on scraps, legal paper, and what ever else was blowing by on the floor while I worked.

Having said that, I don't really like knowing too much about what people think about the work. I believe we talked about that earlier. It's a lot better for me to not know too much or worry too much about it. I especially try to keep that out of my mind while I'm working, so I didn't have any particular hopes or fears while I was making the book.

Actually, one thing that mattered to me very much was that my neighbors, Donavon and Joanie Mitchell, would be happy with it, because they're the ones that connected me to Doris Mitchell who was Donavon's aunt. And they let me go though bags of things that were being thrown out after she died. It was a messy situation because she kept things in a damp unheated basement on a farm and there was hardly anything that was completely intact or didn't have some kind of critter living in it. There were a lot of mice who ran through everything and chewed things up and left their messes, and there was a tremendous amount of mold and mildew, so I just put on a face mask and sifted through for pieces I could salvage.

I suppose in a way this made it easier to use, because it was already in pieces. Had it been well preserved I don't think I could have used it because it would have made me feel horrible to cut things up. But when a piece of paper is falling apart but there is a section that can be salvaged, I tried to salvage it. I had to let a lot of it dry out in our barn after I got it. I really understood what barns are for after that! They are specifically designed to keep air flow going but keep things dry at the same time. Ours is over a hundred years old. It did a beautiful job in helping to make these scraps usable.

I did show the book to Donavon and Joanie and I'm happy to say they were happy with it. I put Doris's picture in the back and they were especially happy to see that. They told me she always wanted to be a writer, and she would have been happy to see herself included in a book about writing. I hope that is true! I sure have a lot of affection for her, though we never met. I know how very lucky I was to have access to the papers she kept for so many years. I even have pages from the homework she did in 1923 and 1924 at the University of Wisconsin. I've been painting monkeys on them. Maybe I already sent you some -- here's one on a page she typed on the last day in January, 1924. It's part of her report on Magnetic Fields.

SPURGEON: Some of the book is structured around what seems like autobiographical moments, which I found interesting because of the way it contrasts against some of your comics that I would guess are occasionally autobiographically informed without being autobiographically driven. Do you have any worries about working from real-life events and folding them into a book like this one? Were there any particularly problems using that material in this book? We're living in a kind of renaissance of memoirs right now, have you seen some of that comics work and is there any you've particularly enjoyed?

SPURGEON: Some of the book is structured around what seems like autobiographical moments, which I found interesting because of the way it contrasts against some of your comics that I would guess are occasionally autobiographically informed without being autobiographically driven. Do you have any worries about working from real-life events and folding them into a book like this one? Were there any particularly problems using that material in this book? We're living in a kind of renaissance of memoirs right now, have you seen some of that comics work and is there any you've particularly enjoyed?

BARRY: The history of making things as a kid and then at some point stopping is something that is probably common to everybody. When I was working on the book I really wished I had another way to tell it besides using events from my own life. I had to find a way to tell it that wasn't just explaining it which is how I do it in my class, and the only way I could think of was to tell some stories about my own experiences. It's a pretty fast way to do it and it's a very old way, but I did wish I wasn't in the book so much.

One Hundred Demons was the first autobiographical book I'd done. What It Is has a lot of autobiography in it as well. But now I hope not to draw myself for a book again for a long long time. There are real limitations when writing autobiography and I don't really enjoy them. I like having characters who can say or do things I don't expect, people who don't exist anywhere but in the story. The feeling of writing fiction is very similar to the feeling of writing from something that actually happened because when fiction is going well, it is actually happening. It's why we scream during the part of

Carrie (my favorite movie) when her hand shoots up out of the grave. Because in some way it is actually happening.

I think one of the reasons people have always thought my work was autobiographical is because of how I learned to work early on from Marilyn Frasca. It's what the book is based on, this idea of an image being something that has an aliveness to it. When you work from that place instead of the thinking place, you end up with some stories that seem pretty real. You also get to be surprised by them in the same way real life surprises us. They aren't always exciting, these surprises, but they are continual. It's the unexpected part of making things that keeps me doing it. Autobiography has less of that for me but there is still plenty enough to work with.

Having said that, I love reading autobiographical comics. One of my absolute favorites is

King Cat by John Porcellino. I also love

Fun Home by Alison Bechdel. Actually the comics I like best tend to be autobiographical or feel as if they are. Chris Ware's work feels absolutely autobiographical even when his characters are women. When he writes in the first person, even though it's fiction, it has a feeling of being true, of having happened.

Ivan Brunetti has written a brilliant book called Cartooning: Philosophy and Practice which gave me the same feeling of a story actually happening even though it's a teaching book. I have no idea how he did it! It's a book about making comics but when I remember it it doesn't feel like a book about making comics, it feels like an actual experience with an actual person.

I was lucky to have been the editor of the next

Best American Comics collection and my only regret is that I didn't get have more comics to chose from. I was able to read hundreds of comics, but I would have liked a thousand much better. Anytime anyone sits down and draws something and writes some words with the drawing, I am really happy to read it and I loved reading every single thing that came my way. The part where I may have failed was that I live in such a rural location that finding comics was hard for me and I didn't realize until too late that not enough would be sent my way through the publisher. If I could have done it over again I would have worked much harder to see many more comics than I saw, especially from people who are making their own little books. I also liked reading the super hero comics quite a bit. Actually I liked reading everything. The only problem I had was when someone used electronic typography. For me half the aliveness of a story is missing when it's not hand-written. Even if the typography is based on actual handwriting, there is something dead about it. It's like artificial flavoring. You can get used to it, but it's nothing like real food.

SPURGEON: Was there anything that stood out to you in terms of the kinds or types of comics, or the aims of the comics you read for the

SPURGEON: Was there anything that stood out to you in terms of the kinds or types of comics, or the aims of the comics you read for the Best American Comics

gig? Did you see any similarities between what people were trying to accomplish, or were there types of comics that you hadn't read before. For that matter, what was it that you liked about the superhero comics you read, and did any of them stand out in a way that you remember which ones impressed you?

BARRY:

BARRY: I adored

Paul Pope's Batman 100. His version of

Batman gave me the same feeling I had when I read

Batman as a kid. There was something so alive and beautifully drawn about it. Unfortunately, DC refused to grant permission to include it in the

Best American Comics of 2008 and it was clear that no DC superhero comic could ever be included in the collection.

So while I was trying to broaden the range of what "Best of American Comics" meant, I was thwarted by the publisher of the comics I wanted to include. It's hard to understand, really. It also put a damper on reading many super hero comics knowing that the chances for inclusion were going to be slim to none. But I read them anyway because I'm just interested in what people are drawing and writing. I was surprised by how seemingly small elements usurped my enjoyment of those stories. The three things that seemed to really remove the flavor are the slick paper they are printed on now, the use of electronic typography instead of hand-written letters, and the computer coloration and shading which somehow deadens what used to be very alive. I didn't realize how much these things added to the aliveness of a comic story until they were gone. I like to believe there is some aliveness there I can't detect for people who don't know any other style of comics and for whom this sort of paper, type and coloration is the norm. I hope there is! I did like reading them but not as much as I like reading old comic books with the same characters on paper that doesn't reflect light back into my eyes and had so much more indication of the human hand at work.

I was really torn about daily strips and I have regret about not fighting harder to keep track of them and include them in the collection because I believe they have really been marginalized in this whole recent comics awareness, and I believe unfairly. My error was not understanding how much I was going to have to do on my own in terms of gathering the comics. I stupidly thought that all kinds of comics would be submitted to the publisher and the publisher would send everything to me.

I didn't know that if I wanted daily comics or even my fellow weekly comic artists I was going to have to hunt all that stuff down from the very beginning and work hard to keep track of it. So I do feel I completely failed in this regard and though my intentions were to really open up the range of comics in this collection, in the end it's not opened up at all. It's mostly art comics. Having said that, I clearly love art comics. They are my favorite kind of comics. But I have regrets here too, because I wish I'd understood the process better so I could have started scouting for comics immediately after I'd accepted the editorship. Still, I got to read several hundred comics and my rule was I had to read everything at least twice and even three times before I decided to include or exclude them. I was amazed by how the mood of the day could affect how I responded to a comic. They seemed to change upon re-reading and it was awhile before I understood that part of that changing element was me. My mood, my alertness, my exposure to the work over time, my familiarity or unfamiliarity with a drawing style or writing style, and how it came back to me while I was doing something else. That was actually something I paid attention to when it happened. What is it about a comic strip that comes back to you after you've read it? And how does it change after you read it a few times?

Comics are more like music to me than like plain old reading, and music changes the more you hear it because there are so many elements -- from lyrics to melody to rhythm to duration in time. Comics have this same mix of elements and just as songs come back to me during my day, so comics came back. And when they did I noticed it and those were the ones I was more likely to wish to include. The thing I loved about this was I could never predict which ones would come back. There are still some comic panels that come back to me all the time.

Kaz's work in particular seems to come back like a song. Who knows why? His work really stays in my head and not just stays in my head but makes me happy when I remember it. How does that work? How can an image that just comes up in your mind make you feel happy? I don't know! But I know that comics can do that.

Don Martin from Mad Magazine did that for me a lot when I was a kid, and so did

Big Daddy Roth's Rat Finks. I just had them in my head like toys and they made me feel better.

Dr. Seuss is in there, too. I think that guy is a cartoonist and I think I may have learned quite a bit from him.

Seriously, that job of picking comics was pure heaven. I knew I'd only have one shot at it and thus the regrets of what I wasn't able to do. I'd do it again in a heart beat!

SPURGEON: Lynda, I understand you're going out on the road in support of this book, at least to Comic-Con International. Are you looking forward to that? Have you ever done those kinds of appearances before? Are you comfortable with making personal appearances and doing other things that promote a work? We've maybe touched on this a little bit, but does the fact that this book is such a direct communication to the readers on the subject of making art change the way you'll interact with people in support of it?

BARRY: I never pictured myself going out on the road to support the book, but I don't think it will be so different than what happens during the first hour of the class I teach where I give a little talk about the process I use for writing. I am very much looking forward to going only because it gets my mind off of our home being lost to the wind plant coming in. I can't call it a farm any more. There is nothing "farm" about rows of industrial turbines 40 stories tall. So when I get away I actually feel like myself again for a bit and can remember the rest of the world, and actually be light-hearted for a little while.

I've been teaching for almost 10 years and I've given talks on and off for the last 30 so though they still make nearly unbearably nervous before hand, once I'm doing it I'm all right. The talks I gave when

One Hundred Demons came out will be a lot like the talks I'll give for

What It Is, which is basically about the role of images, memory, making things and mental health. In a way the talks are about the people listening to them. It's pretty interactive. What I don't know yet is if I'll be bringing some sort of visual support for the talks. I know it makes sense to bring pictures to look at when you're a cartoonist, but I'm so used to no-tech seat-of-the-pants style speaking and at the moment I have no idea how to organize a power point presentation. I could learn to do it if it was about wind turbines! But about my own work I'm less motivated.

SPURGEON: Were you aware of your name being used as an example of someone that could have or should have been included in the Master of American Comics exhibit? And in light of that kind of institutional event, what have you thought about the surge in comics interest this decade, given that you're one of those artists that started the movement that drove what would eventually become that attention paid to comics, and even as we discussed your own initial, primary market seems to have not shared in this comics renaissance?

SPURGEON: Were you aware of your name being used as an example of someone that could have or should have been included in the Master of American Comics exhibit? And in light of that kind of institutional event, what have you thought about the surge in comics interest this decade, given that you're one of those artists that started the movement that drove what would eventually become that attention paid to comics, and even as we discussed your own initial, primary market seems to have not shared in this comics renaissance?

BARRY: I don't actually know about the Master of American Comics Exhibit. What is it? I may be much more isolated from all of this than you imagine! I never think of myself as someone who started anything at all. I actually feel very much out of the loop when it comes to cartoonists. I have one close cartoonist friend, Matt Groening, and a couple I adore but haven't spent a lot of time with like

Art Spiegelman, Ivan Brunetti and especially Chris Ware, who I believe may be the one who says "Hey, you guys, what about Lynda?" when there are shows or collections, he's always been a sweetheart to me, but other than that, I'm not ever invited to the party and I really don't know anyone and I've even gotten the feeling I'm actively disliked by other cartoonists though I don't know why, or if it's true or if it's just the left-over being-a-weird-kid paranoia. I don't know! I don't think I want to know! I just stay home on the farm and fight 40 story turbines all day. (see the result at

betterplan.squarespace.com updated daily if I'm in town!)

You know who I think has been really seriously and unfairly marginalized? It's Matt Groening. Prior to the success of

The Simpsons, everyone who cared about comics knew what he was doing was original and hilarious and ground-breaking. But then

The Simpsons came and it's as if his other work doesn't count anymore. I can tell you from having done book signings with him pre-

Simpsons that lines of people who came to see him went out the door and wrapped around the building. People came to see me too, but usually to ask where the bathrooms were. Another ground-breaker who never has gotten credit is

Heather McAdams. I hope you don't say "Who?" I think she's incredibly brave and brilliant and completely under recognized. She and I don't get along, but I still love her work completely.

So in terms of being a cartoonist I feel like the very uncool Quasimodo cousin at the comics cousin picnic. Sometimes it's made me feel lonely, other times I just jump onto the rope and ring the dang bell and then jump off and run back into the fog.

SPURGEON: That's everything I have. With your permission, I solicited questions from CR

's readers. Here are five that struck me as potentially interesting. Gus Mastrapa wondered if there was any back story to "those 'funk queen' shout outs that Matt Groening used to give her in the front of the Life in Hell

collections."

BARRY: The "funk queen" shout outs are actually a response to the line I always used to put in my books in the copyright info that says "Matt Groening is Funk Lord of USA" which I actually included in What It Is. "Funk Lord of USA" comes from a high school kid who was working in the print shop at his high school and was making stationary for himself. He didn't have room for the word "the" in his design so it just had his name and "is Funk Lord of USA" -- this was probably in 1980 or so. I stole it and always put Matt's name in front of it. Because Matt Groening actually

is Funk Lord of USA. He responded with many names for me, but none kick ass the way "Funk Lord of USA" kicks ass. Take it to the

judge!

SPURGEON: Tim O'Shea wondered if anything sticks in your memory about the Off-Broadway version of The Good Times Are Killing Me

.

BARRY: Everything sticks in my memory about the theatric production of

The Good Times are Killing Me. The first version was in Chicago and the cast was mind meltingly wonderful, brilliant, and all the people who worked on every aspect of it were superb. And the second version in New York was just as mind-melting. Those were the happiest days of my life and I loved living in New York and having an actual job to go to in the morning. To me it's like this part of my life, a whole other living planet of my life that I somehow got launched into and then launched out of. But those working with the people on those two productions are the most joyful happy days I've ever known. Like a dream, a complete supernatural dream. I can't believe it even happened to me. I know this is so general, and I could get into nitty gritty specifics of the 100,000 avenues of hilarious things that happened, but I'll let the word joy, followed by the word gratitude do the heavy lifting here. If Mr. O'Shea has a specific question, I'll be glad to give a specific answer. But it really was magic.

SPURGEON: Someone who goes by "HT" wonders, "Who writes the descriptions for the Lynda Barry artwork sold on eBay? They are written in third person, but sound like she might have written them herself."

BARRY: I have an eBay helper! Her name is always Betty Bong, but Betty Bong isn't always the same person. Kind of like how Ronald McDonald isn't always the same person but he is always Ronald McDonald. By the way, I vote Ronald McDonald for the most scary commercial character ever. A clown with combed hair. If you are a clown, please do not comb your hair. But Betty Bong has been the same actual person for several years now and if you ever take my writing class you will meet her and learn her real name! I do sometimes write the descriptions. You can always spot when I do it because I'll go on about industrial wind turbines. I HATE THEM! Come visit my website! Betterplan.squarespace.com. I! HATE! INDUSTRIAL! WIND! TUR! BINES! So if you see #$%& related to industrial wind turbines that in the description you know I'm at the keyboard! By the way, THANK GOD FOR EBAY! I'd be so in trouble if I didn't have my little eBay kool-aid stand. I'm thankful for the people who buy my art on eBay. It keeps me from having to get a job.

SPURGEON: Jackie Estrada asks, "Do you still go to Jazzfest in New Orleans? Any thoughts on the post-Katrina situation there?

SPURGEON: Jackie Estrada asks, "Do you still go to Jazzfest in New Orleans? Any thoughts on the post-Katrina situation there?

BARRY: I haven't been back to New Orleans since Katrina. I haven't been able to bear it. That was the most horrible time, the most shocking terrible and life changing event, to see an entire city left with no help, yet cameras rolling. I can say it changed me completely. The word "Katrina" is painted on the back of my old hoopty van. I don't think whatever broke in me from all that ever got fixed. It's like someone you love being murdered. You don't get over it. I'm not over it.

SPURGEON: I'll end with a slightly longer one from the cartoonist and painter Frank Santoro.Would you ask her about conscious and unconscious story structures? She uses a grid a lot but then her sense of pacing and timing for longer works is still informed by this 4 panel pacing that often it doesn't allow the narrative to breathe. Everything can quickly become a gag.

One Hundred Demons

is different from a weekly strip but its still packed. Is she going to write a slow-paced summer kind of ale someday that's notso intense?BARRY: No, I don't think I'll ever write "a slow-paced summer kind of ale someday that's notso intense."

Please let Frank know he can give up on me. I will always write gag based, over packed, suffocated narrative with no air holes punched in the jar ever.

It is my destiny.

*****

* all art from

What It Is except the inset self-portrait and the panel from

Batman Year 100

*****

*

What It Is, Drawn and Quarterly, Hardcover, 208 pages, 9781897299357, May 2008, $24.95

*****

*****

*****

posted 4:00 am PST |

Permalink

Daily Blog Archives

November 2019

October 2019

September 2019

August 2019

July 2019

Full Archives