January 29, 2012

CR Sunday Interview: Robert Venditti

CR Sunday Interview: Robert Venditti

Rob Venditti

Rob Venditti is the kind of creator I don't get to talk to as often as I'd like, so I greatly appreciate him taking the time to speak with me. Venditti is a comics writer best known for the

Top Shelf Productions project turned major movie vehicle

The Surrogates. If it's true that every time someone gets into the comics industry the way they got there dies behind them, then I can imagine a significant number of people were made sad when Venditti's particular, remarkable pathway faded from the real of possibility. His is the classic story of mailroom to working professional, and he reflects a bit on that journey below. Today he splits time between his now-expanded duties at Top Shelf and his writing career, which includes work on

the Percy Jackson franchise,

one of the new Valiant titles, and his own comics.

Venditti's latest work of his own creation is 2011's political/medical thriller

The Homeland Directive, about a plot by Americans against Americans, ostensibly to benefit still other Americans. The following was conducted via e-mail over a ten-day period and edited slightly by me for flow. -- Tom Spurgeon

*****

TOM SPURGEON: You didn't read comics until you were in your twenties. What prompted you to begin reading them then? What were some of the comics that really struck you, that really had an impact on your reading of them?

ROBERT VENDITTI: I was working in the stockroom at a

Borders Books & Music in Florida, where I met another employee named Marques. We became good friends -- still are -- and he was always trying to get me to read comics. I was in grad school at the time, earning my masters in creative writing, and I had the same misconceptions about comics that a lot of academics had back then -- that they were a lesser artistic medium. This was around 2000, so it was a much different time. Even at Borders, which would later become the vanguard of comics' acceptance among book retailers, the graphic novel section consisted of a couple of shelves of dog-eared trades like

Batman vs. Aliens, or whatever.

During those long days in the stockroom, Marques would tell me about this comics story or that one. None of the stories really appealed to me, though, until one day he told me about

Kurt Busiek's Astro City. Specifically, the "

Confession" story arc (Vol. 2, Issues #4-9). The story dealt with a priest turned superhero, and that idea hooked me. So I hunted down the back issues, read them, and was all in. The complexity of the story, the conflicts driving the characters . . . the scales fell from my eyes, as it were, and I realized comics was a medium with tremendous storytelling potential. I read as much of the

Astro City run as I could find, and then started branching out into other things.

Something that intimidated me, though, was all of the continuity involved in the

Marvel and

DC lines. I didn't feel like they had books I could pick up cold and know what was going on. So I went looking for other series with relatively low numbers of issues. The

America's Best Comics imprint had just started up at

WildStorm, and I remember seeing the first issue of

Tom Strong -- this great cover with Tom Strong swinging a hammer at an anvil -- and I bought it. I enjoyed it and went looking for other comics written by this guy

Alan Moore. Oh, he wrote something called

Watchmen? Okay, I'll try that. Everything just kind of snowballed from there.

SPURGEON: Do you think you read comics differently than those creators and readers that have a connection going back to childhood -- do you find you're less hampered by a nostalgic reading of certain works, for example?

VENDITTI: I don't know if it helps or hurts me, but I do think having not read comics until my mid-twenties lets me see them differently as a writer. My influences come from other places, and hopefully that lets me bring a fresh perspective to the page.

SPURGEON: Was there a process in educating yourself in terms of the specifics of writing comics? I know there are scripts out there, and you can certainly reverse engineer those things; what was involved with you getting to the place where you felt you could make a comics script?

VENDITTI:

VENDITTI: As far as the actual formatting of comics scripts, it's pretty much what you said -- I found examples of other writers' scripts and reverse engineered them. But long before I sat down and actually did any writing, I felt like I needed to become more familiar with comics as a storytelling medium. I read

[Will] Eisner's

Comics & Sequential Art and

Graphic Storytelling,

[Scott] McCloud's

Understanding Comics, and even

[Dennis] O'Neil's

The DC Comics Guide to Writing Comics. I'm sure there are more books on the subject today, but in 2000 that was about all I could find.

One of the biggest hurdles for me was that the prose I was writing in grad school tended to be long on description and interiority and short on dialogue, because dialogue was something that always intimidated me. Comics relies much more heavily on dialogue, so I really had to come out of my shell there.

When I did finally sit down and start writing, I was more or less in a vacuum. I had no idea who the artist was going to be when I wrote

The Surrogates. I didn't even know any comic book artists I could bounce pages off of to see if I was making an idiot of myself. The script ended up being really verbose, with panel descriptions that went on forever. Camera angles and panel dimensions and descriptions of every last potted plant. I've changed quite a bit since then. Printing out the script for the second book in the series,

The Surrogates: Flesh and Bone, requires the felling of far fewer trees.

SPURGEON: Who was influential on you as a young person in terms of prose? The authors that you've mentioned in interviews -- King, Clancy, Adams -- are all very popular authors, and their work is very accessible. Is there someone you think is an influence on your work that might be harder for other people to see in it?

VENDITTI: I was an English major as an undergrad, and my post-grad work was in creative writing, so I've read much more of authors like

Hemingway and

Gore Vidal than I have of King, Clancy, or Adams.

SPURGEON: [laughs] Right.

VENDITTI: If I had to pick a favorite book, it would be either

1984 or

Of Mice and Men.

Of Mice and Men is just amazing. Every time I read it, I think this time -- maybe this time -- George and Lennie will get to live off the fat of the land.

Now, I doubt anyone is ever going to read

The Surrogates and say, "Hey, I bet this writer likes

Steinbeck." But I will say that the principles of the literary novelists I studied -- writing character-centered stories with a straightforward approach -- is something I strive for with my comics work. I want to apply those principles to genre stories.

SPURGEON: How much do you read now? Some writers claim to have a very different relationship to others' writing when they start publishing their own work. Are you open to be influenced by a new voice, or is that something you might even avoid?

VENDITTI: I definitely don't read as much as I used to, but that isn't because the desire is lacking. I just don't have the time. My tastes have also changed pretty significantly from what they were ten years ago. I spent so many years in college reading nothing but fiction, so now I tend to prefer nonfiction. I will say, though, that if I'm writing something sci-fi like

The Surrogates, I won't be reading sci-fi at the same time. You spend so much time with the genre you're writing, you want to get away from it in your free time.

I've found that the books I appreciate the most, particularly when it comes to comics, are the ones I know I could never write. As I said, I take a pretty straightforward approach to writing, but that doesn't mean I'm not a fan of more outside-the-box storytelling.

Skyscrapers of the Midwest just floored me. My books tend to be serious in tone, too, so when I read something like

Afrodisiac or

Tales Designed to Thrizzle, I can really appreciate the creativity that went into them. But my all-time favorite is

Eddie Campbell's Alec. Eddie's sense of pacing and his comedic timing is dead-on. If there are better comics out there, I have yet to read them.

SPURGEON: Tell me about the decision you made to want to start writing comics. What was the specific appeal of that kind of idea, what was it that you liked about comics that you wanted to make a home there as opposed to screenwriting or prose?

SPURGEON: Tell me about the decision you made to want to start writing comics. What was the specific appeal of that kind of idea, what was it that you liked about comics that you wanted to make a home there as opposed to screenwriting or prose?

VENDITTI: Going back even farther than my time at Borders, when I was really young, I wanted to be an artist. To me, there was no higher profession than to draw

Bugs Bunny cartoons. But I was just bad at it. I knew, no matter how hard I worked, I'd never be any good, and I think I turned to writing stories as a way of describing in words what I couldn't draw with my hand. So when I started reading comics, it occurred to me that here was a medium where I could write the words, and someone else could draw the images, and that's probably as close as I was ever going to get to that original childhood ambition. Why it took twenty-six years for that rather obvious notion to dawn on me, I have no idea.

That's not to say that I won't ever try another type of writing. I placed my first short story out of grad school in

Berkeley Fiction Review, but by the time it was printed, I'd already started down the comics path. I'd like to return to prose someday, though.

SPURGEON: You famously starting working at Top Shelf doing various low-end editorial busy work like answering the mail before you pitched The Surrogates

. Was that always your intention, to begin pitching work? What's it like pitching and then developing work with Chris Staros?

VENDITTI: Actually, it was quite a while before I moved up to doing editorial work. I started out in the warehouse, mailing out web orders and shipments to retailers and stuff like that. (I was living in an apartment at the time, so when the aforementioned story was published, I had

Berkeley Fiction Review FedEx the copies to the Top Shelf warehouse. The FedEx driver dropped it off, and I kept right on packing orders.) My end goal was always to write comics, but I didn't make that the focus of my time there. I wasn't always pushing scripts in front of Chris or anything like that. He was paying me to do a job, so that needed to be the main focus. Plus, I knew Chris was a good guy and really well-respected in comics, so I hoped I'd be able to work the convention circuit with him and meet other industry pros. Happily, that turned out to be the case.

As for Chris, what can I say? He's just a quality person and a solid editor, too. Look at the number of people he's helped introduce to comics readers. Outstanding talent like

Jeff Lemire,

Jeffrey Brown,

Matt Kindt,

Craig Thompson,

Nate Powell. The list goes on. I was there the day

Andy Runton came to the Top Shelf booth at

MegaCon and handed Chris an eight-page

Owly minicomic. Now Andy has a series of books, t-shirts, toys, and so on. I stand behind the table at conventions with these guys, and I wonder who let the imposter into the room.

The thing about Chris's style that I really appreciate is he doesn't try to turn your story into his story. Instead, he finds out what it is you're trying to say, and he points out the places where you drop the ball, or maybe aren't saying it as clearly as you think. You can't ask for much more from an editor than that.

SPURGEON: When you think on the whole experience of The Surrogates, from its publication to its purchase for the motion picture, to the movie coming out, what are the first memories to spring to mind? What are your enduring recollections of that whole experience?

VENDITTI: As far as the film goes, definitely my first visit to the set. I had no idea at all the level of effort and expense that goes into making a major studio film. I was such a novice about the whole process I thought scenes were filmed in the same order they appear on the screen. Seeing all of the people involved, talking to the prop guy, and the set dressers -- it's mindboggling how detailed their jobs are and how efficient they are at them. I worked in a lot of restaurants growing up, so at one point I went inside the catering truck and watched the staff make lunch. I look back on the whole experience with nothing but positive emotions.

Overall, my best memory of

The Surrogates is probably when I found out it was going to be published. My cell phone rang, and I saw it was Chris, but I couldn't answer it because I was working on the sales floor at Borders. I went to the back room and called him back, and he said he'd read the script and talked to Brett Warnock about it, and they'd always wanted to do a mainstream type of story, so Top Shelf wanted to publish it. I hung up the phone and blurted the news to the only other person around, an employee named Ginia. I said, "Top Shelf wants to publish my book!" She smiled kindly, but I don't think she knew what I was talking about.

SPURGEON: One thing I never ask enough of writers is how you write, the practicalities of getting ideas on the page. Do you keep a notebook? How did you develop the idea that became The Homeland Directive in practical terms? How much of the story do you know by the time you start writing a script, and how much of the writing is a process of unearthing the story as you go? Is it a script first, even?

VENDITTI: I'm a highly organized writer, so I don't start scripting until the entire story is mapped out in my head. Once I get an idea for a story, I'll spend however long it takes -- days, weeks -- taking notes. I'll jot down characters and snippets of dialogue, and I'll plot out the major arc of the story. If it's a story based in the real world, like

The Homeland Directive, I'll do a fair amount of research, too. The research will go into the notes until I have what amounts to several pages of plain, white paper covered in barely legible handwriting. Once I know what my beginning, middle, and end are, I'll start writing. I stick pretty close to the outline, but that doesn't mean I don't let things develop organically as well. The best moments are when you're writing a story and something unexpected happens, and it's almost as though the story is writing itself. As a writer, you live for that.

For me, the process of writing isn't about answering questions or stating a specific point of view. I'm not an essayist. A story idea will interest me because it deals with a question I don't know the answer to, and I want to explore that question and present it to the audience. For

The Surrogates, the primary question would be where is the line drawn between good technology and bad technology? What value system do we use to define that? With

The Homeland Directive, it's how do we as Americans -- citizens and government -- reconcile our desire to be safe with our desire to be free? I still don't know the answers to those questions, even though I've spent enough time considering them to write books about them. Literally. Maybe the questions can't be answered.

SPURGEON: There are a couple of things out there on-line as we're e-mailing about the writing process as it pertains to comics. One is a short piece by Warren Ellis emphasizing that a script exists to get the best work possible from the artist; the other is a public falling-out between two creators over creative differences that were planning to work together on a Kickstarter-funded book. How do you approach the act of collaboration in terms of its give and take? With

SPURGEON: There are a couple of things out there on-line as we're e-mailing about the writing process as it pertains to comics. One is a short piece by Warren Ellis emphasizing that a script exists to get the best work possible from the artist; the other is a public falling-out between two creators over creative differences that were planning to work together on a Kickstarter-funded book. How do you approach the act of collaboration in terms of its give and take? With The Homeland Directive

say, how much of what we end up reading clings to your script and how much involved Mike's contributions in terms of approach or style or even the nuts and bolts of the narrative?

VENDITTI: The only project I've ever written knowing in advance who the artist was going to be is

Flesh and Bone -- I knew

Brett [Weldele] was the artist because we'd already done

The Surrogates together, and we were continuing the series. As with

The Surrogates,

The Homeland Directive was written over a year before the artist was attached. Even with the

Percy Jackson adaptations, the majority of the first one was written before

Attila Futaki was signed. So when it comes to things like style and coloring choices, I don't write them into the script. Even if I did know who the artist was in advance, I still don't know that I'd try to coach them like that. Comics made by a writer/artist team are collaborative by necessity, and I want the artist to feel like they can bring their own sensibilities to a project. It has to be fun for them, too. I try to challenge myself to do something different with each new project, and if the artist wants to challenge themselves, they should feel free to do so.

When Mike first came onboard, he told me he had some new techniques he wanted to try out. I said go for it. He said he wanted to use double-page spreads for the action sequences. I said no problem. If it keeps the artist interested and engaged, then that enthusiasm will find its way onto the page. I keep my comments to a minimum, and reserve them only for instances where there's a break in continuity or the storytelling isn't clear. Nine times out ten, it's the former. "You drew the coffee cup with a handle here, but in the previous panel it doesn't have a handle." Minor stuff like that.

I've never butted heads with anyone I've worked with -- artists, editors, or otherwise. I try to be as agreeable as I can be. If an artist came in and wanted to rewrite the plot or the dialogue, I wouldn't want that, but that hasn't happened.

SPURGEON: Do you have a different relationship with an artist doing some of your work-for-hire gigs than you do on something you're generating from scratch? Maybe not just in terms of the kind of story, but the fact that you probably have an editor on the former that's at least partly responsible for seeing that the team works together?

SPURGEON: Do you have a different relationship with an artist doing some of your work-for-hire gigs than you do on something you're generating from scratch? Maybe not just in terms of the kind of story, but the fact that you probably have an editor on the former that's at least partly responsible for seeing that the team works together?

VENDITTI: Regarding a lot of the things we talked about above, my relationship with the artists on the work-for-hire jobs is for the most part the same. I suppose the only difference is when I suggest art changes, the editor has final say over whether they get made or not. With the

Percy Jackson material, there are essentially two editors:

Christian Trimmer, who oversees the projects for

Hyperion, and

Rick Riordan, the author of the source material.

Writing an adaptation has a substantial effect on the way I script, though. If I deviate from the source material, I embed red-fonted notes within the script to explain why I'm doing it, so everyone understands what my thought process is. I also feel more urgency to finish the script as quickly as possible because I prefer to have something entirely written before an artist starts penciling. That leaves me the freedom to make revisions all the way back to page one if need be.

SPURGEON: There are a few formal approaches here I wondered if you could comment on. The first is the layouts; the pages are very dense, but the layouts within those pages seem to vary wildly. How important was it to you to have this very packed page and to use a variety of approaches on that page?

VENDITTI: My scripts tend to average between six and seven panels per page. Not too crowded, but enough panels that you can tell a lot of story in a two-page spread. As far as layout, I leave that up to the artist. Again, we're getting into an area where if you don't know who the artist is beforehand, then you can't really script for that. Brett likes a page with three tiers. Mike is more varied in approach. They're both equally valid.

If I feel like something needs to be a certain way because of the storytelling, I'll note that in the script. For example, if I want an inset panel as part of a larger image, or if I want two panels to be side by side, so I can use the gutter a certain way. I'll also say if I think a panel should run vertical or horizontal, if one or the other is necessary.

I'm probably making it sound as though my scripts are nothing but dialogue. That certainly isn't the case. I'm pretty specific about the action I want to see in each panel, how the characters react, and what their emotions are. I'll also convey visual details regarding the setting and the position of the characters in relation to their surroundings and each other. Most importantly, I want the page breaks to happen where I specify. I'm a stickler about that.

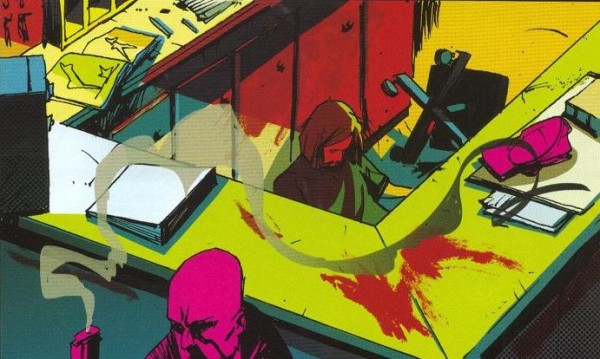

SPURGEON: Another thing that kind of leaps out is the use of color: limited at times, wildly expressive and kind of swirling at others. How would you describe what you're attempting with the color there -- or if that's not you, what the book achieves by these shifts in approach?

SPURGEON: Another thing that kind of leaps out is the use of color: limited at times, wildly expressive and kind of swirling at others. How would you describe what you're attempting with the color there -- or if that's not you, what the book achieves by these shifts in approach?

VENDITTI: One of the things I've learned from the artists I've worked with is how important color can be to storytelling. Coming from a non-comics background and starting out with more traditional mainstream fare, that wasn't something that was immediately obvious to me. All of the comics I read in the beginning had coloring styles that were based in realism, so that was the way I tended to think. It wasn't until I started working for Top Shelf and started reading more indie comics that I realized the extent of the possibilities. Which isn't to say that there isn't a time and place for realistic coloring; there absolutely is. It just doesn't always have to be that way.

More than anything, the coloring in

The Homeland Directive establishes the mood in each scene, but it also reinforces the subtext. During the scenes in the Oval Office, Mike uses a hazy gray coloring scheme, which supports the political tone -- after all, politics isn't as black and white as politicians would like us to believe. During more action-oriented scenes, he goes heavy on red to bolster the violence taking place.

My reaction when I saw the first colored pages of the book was that it was completely unlike anything I'd ever seen, and in a completely positive way. And it's nice to be able to learn from the artists I work with. As I get more projects under my belt and hopefully grow as a writer, I'm starting to incorporate into my scripts the things I've picked up from watching the people I've collaborated with.

SPURGEON: Last formal thing: the backgrounds also exist on a wide spectrum: sometimes they're rendered, others they're suggested, and sometimes they're dropped altogether. Is this a pacing thing with the book? Because certainly the eye moves in different ways with different amounts of visual density. How important is it to you as a writer to pay attention to how reacts to the page in the ways that move it from here to there to different parts of the page?

VENDITTI: It's extremely important, and I think as I writer, you have to be cognizant that sometimes there can be too much going on with a page. The individual notes can get lost in the cacophony. I can honestly say, though, it was never an issue with Mike. I didn't have any problem reading the pages, and I didn't figure anyone else would, either. Comics readers are a sophisticated bunch.

SPURGEON: More generally, now that you're doing some outside work for employers -- working on the

SPURGEON: More generally, now that you're doing some outside work for employers -- working on the Percy Jackson

material; now doing at least one of the Valiant books, if I'm remembering correctly -- has that changed your perspective on your own work at all? Has that been informative to you in terms of how you view your own writing, your strengths and weaknesses, and so on?

VENDITTI: That's a good question. I don't know that I've ever thought about it that way. I'd say working on the Hyperion adaptations taught me that I'm not always as economical with the panels and dialogue as I could be. Page space is precious, and every panel and word should count. If there's one thing adapting a 375-page novel -- a first-person novel, where all of the interiority that prose does so well has to somehow be made exterior -- into 125 pages of comics will teach you, is how to say the most with as few words as possible. I could've done more self-editing in my earlier work.

Here's something else: Before I started scripting the first issue of

X-O Manowar for Valiant, one of the things Executive Editor

Warren Simons said to me was that my characters don't always have to be so rational. Stories should make sense, and the internal logic should hold up, but characters don't always have to behave rationally. I really took that to heart. Looking back on all of my creator-owned work to date, off the top of my head, I don't know that I can point out a single instance where a character of mine behaved irrationally. That just isn't, for lack of a better word, rational. So I'm letting loose and allowing characters to be more spontaneous, which opens up whole new avenues for storytelling.

SPURGEON: What makes a thriller -- or however you might define the genre employed in

SPURGEON: What makes a thriller -- or however you might define the genre employed in The Homeland Directive

-- a suitable vehicle for the questions you're asking? I'm interested in the more formal aspects, such as the fact that a thriller usually demands a reduction of an issue into a situation facing a few individuals. Or are the questions you're asking about the demands we place on government, do those exist regardless of how you might tell the story?

VENDITTI: I think the questions are a constant, and it doesn't really matter which genre you choose to explore them in. In the early stages of

The Homeland Directive, I had two separate stories in mind, one science fiction and the other a political/medical thriller (at least, that's how I categorize it). I went with the latter because I'd just written

The Surrogates, which is heavily sci-fi, and I didn't want to do tread the same ground again. Had I gone the sci-fi route, though, the themes and subtext and the central question of the story would've been the same.

SPURGEON: Is it fair to say that in addition to asking the question about how we demand certain things from our government that may clash, you're also asking and maybe even a question about the limits to political expediency in crafting a solution to such questions? Because while there are some gray areas in terms of the questions raised, I'm not sure I ever doubted for whom I was supposed to be rooting.

VENDITTI: Sure. It's clear who the reader is supposed to root for, but that doesn't mean the antagonist can't be sympathetic. In some respects, we put government in an impossible position. We demand they protect us absolutely from the terrorist threat, but when they try to institute policies that we view as being intrusive, we rebel against them. If we were to be attacked again, however, we'd demand to know why they didn't protect us.

I was on a commercial flight flying into Philadelphia on the first anniversary of 9/11. There ended up being an incident during the flight, where a passenger was being disruptive. Things escalated, and two plainclothes air marshals decided to arrest the passenger and spend the remaining 45 minutes of the flight guarding the cockpit with their guns drawn. All of this happened less than ten feet from me. When I tell you one of the air marshals had his gun pointed right over my wife's head, I'm not exaggerating in the least. The thing is, though, in my opinion, the air marshals acted appropriately. Like I said, this was the first anniversary of 9/11, and we were flying into one of the most target-rich cities in the country. They did what they felt they had to do to keep us safe.

The next morning, the incident was all over the news. Several passengers had spoken out, saying how terrified they were, making it sound like the air marshals were waving their guns all around the cabin. It made me wonder: If the same events had taken place, but there hadn't been any air marshals to arrest the disruptive passenger, then those same people might've complained that they were terrified that a passenger could engage in disruptive behavior on a commercial flight and no one was there to stop it. "What if that passenger had been a terrorist?" and so on.

Now add to that a second layer of contradiction, where the freedoms we fight so hard for in the face of government intervention, we often give away willingly for the sake of something as simple as convenience. In

The Homeland Directive, the government doesn't use satellites or cameras on street corners. There are no listening devices in bedside lamps or homing beacons under the bumpers of cars. They don't need them. There is already so much self-induced surveillance going on. Whether it's Facebook or smartphones or credit cards or prepaid electronic toll devices... we already leave a digital record of just about everything we do. Not because we have to, but because we choose to. Because it makes life easier.

These contradictions must be terribly frustrating for the people we entrust and elect to deal with the issue of public safety. I'm not passing judgment or assessing blame. I tweet from my iPhone while I'm zipping through the tollbooth just like everyone else does. Okay, maybe I'm not that bad, but you see what I mean. I don't know what the answer is here. I'm just aware there's a question.

SPURGEON: Was it important to you to show that this menace was confronted by other people working in the system as opposed to outright outsiders being portrayed in a struggle against government forces? How did that appeal to you? There's certainly a history of entertainment that focuses on the honorable efforts of public officials, from High And Low to Contagion.

SPURGEON: Was it important to you to show that this menace was confronted by other people working in the system as opposed to outright outsiders being portrayed in a struggle against government forces? How did that appeal to you? There's certainly a history of entertainment that focuses on the honorable efforts of public officials, from High And Low to Contagion.

VENDITTI: Again, this is one of those instances where I didn't want to write as though I was coming down on one side or the other. Almost everyone in the story works for the government in some capacity, and it was important to me that I show the good people and not just the wrongdoers. It's also why I intentionally didn't have the conspiracy go all the way up to the Presidency. Once you bring the President in, there can be a tendency for the audience to paint all of government with a broad brush. It bothers me when there's a story about government -- book, film, especially in the press -- and everyone from the government is portrayed in a negative light. I don't think that's reasonable.

SPURGEON: Rob, I should have asked this earlier, but I'm not sure I know exactly how your work day breaks down. I take it that you're still doing work for Top Shelf, but I don't know that for a fact? What is your workweek like?

VENDITTI: I do still work for Top Shelf, though I'm not full-time anymore. The way the day breaks down, I work on whatever needs to be done at any given moment. Sometimes that's a script I'm writing, and other times it's something for Top Shelf. I'm always multitasking, unless I'm behind the Top Shelf booth at a convention, and someone comes up to buy one of my books. Then it's synergy!

It'd be hard to explain just how important my job at Top Shelf has been to my career as a writer. Aside from the obvious benefits like having them publish my first book, there are so many intangibles, too. One I'd like to stress, though, something that might not occur to most people, is that when you're in the early stages of your career as a writer -- and I like to think that's where I am -- it pays to have a day job. I have a family, and they deserve a good life, so knowing the bills are paid takes a ton of pressure off. And it has kept me from ever taking a writing job because I had to put food on the table.

There's a tendency to assume that once your first work is published, everything else will fall into place. You can quit your day job and live the rest of your life in the Shangri-La of professional writerdom. Don't do it. The day job is what helps you ensure that the early stages of your career are going to happen the way you want them to, on your terms, instead of the way they had to out of necessity. My happy circumstance is that I actually enjoy my day job -- and it contributes to my career as a writer, and vice versa.

SPURGEON: How big a role do you see works like The Homeland Directive

playing in your career as it continues to develop? Is there a perfect mix of projects for you? How studied and planned are your career objectives as a writer?

VENDITTI: Everything I've written and continue to write -- whether it's work for hire or not -- I'm working on because I want to. Somewhere recently I read a piece by someone suggesting that as a writer you should brand yourself consistently, so you become known as the person who writes sci-fi, or thriller, or horror, or whatever, because that consistent brand identity will build your fan base and ultimately make you more successful. If you look at what I've done to date, it's pretty much the opposite of that. I did sci-fi with

The Surrogates, then went to thriller with

The Homeland Directive. Then I switched to adapting a series of middle-grade novels, and now I'm working on a monthly mainstream comic book series. One of my unannounced projects is adapting a young adult gothic romance novel. I'm kind of all over the map.

Maybe I'm ignoring the branding advice at my own peril. I think it all goes back to what I was saying earlier, that I want to give the artist the freedom to challenge themselves. Because that's what I look for with my own projects -- to do something different, to challenge myself with new kinds of storytelling. That isn't to say I won't go back to any of those earlier genres, or even that there aren't common threads running throughout some of them. Certainly

The Surrogates,

The Homeland Directive, and now

X-O Manowar all share an aspect of technology. They're also all very different.

Going from

The Surrogates to

Percy Jackson, one might not see the connection. But when I was offered the

Percy Jackson project, I was coming off my experience seeing

The Surrogates adapted to film. Anyone familiar with both the book and film versions of that story would probably agree that for the first fifteen minutes they're pretty similar, but then the film heads off in its own direction. That isn't a judgment about one being better or worse than the other. I wanted the people involved with the

Surrogates film to have the freedom to do what they wanted with it. I mean, what do I know about making an $80 million movie? I got out of the way and enjoyed watching it from the sidelines. I started wondering, though, if that level of change is an inherent part of the adaptation process. What better way to find out than to take on an adaptation myself?

Compare

The Surrogates and

The Homeland Directive. One has a small cast of characters with a male lead, and the other has a large cast of characters with a female lead. In

The Surrogates, you know what the antagonist's plan is, but not his identity. In

The Homeland Directive, you know who the antagonist is from the opening pages, so his plot becomes the story's main reveal. Those were all conscious choices. So I guess if I have a plan, it's to keep doing projects that interest me and take me outside my comfort zone. And hopefully not lose any readers along the way.

*****

*

Robert Venditti

*

The Homeland Directive, Robert Venditti and Mike Huddleston, Top Shelf, 144 pages, 9781603090247, June 2011, $14.95

*****

* photo of Rob Venditti from I think 2010.

* the

Tom Strong cover mentioned

* one of the books Venditti used to familiarize himself with the medium

* an image from

The Surrogates

* an image from

The Homeland Directive

* cover to a forthcoming

Percy Jackson project

* some of the wild colors employed in

The Homeland Directive

*

X-O Manowar

*

The Homeland Directive shows off its thriller side

* public officials are at the heart of

The Homeland Directive

* image from the cover of

The Homeland Directive (below)

*****

*****

*****

posted 4:30 am PST |

Permalink

Daily Blog Archives

November 2019

October 2019

September 2019

August 2019

July 2019

Full Archives