September 8, 2007

CR Sunday Interview: Warren Craghead

CR Sunday Interview: Warren Craghead

*****

As Bill Randall points out

in his excellent overview of Warren Craghead's career, Craghead is one of the more productive, compelling, and almost completely overlooked verbal-visual artists working today. I first saw Craghead's work 11 years ago in his Xeric-sponsored release

Speedy. That book and a few smaller mini-comics the artist produced during that period felt as thrilling and potent as any young cartoonist's work to emerge that decade. Craghead bent comics' formal properties in a way that yielded new thematic ground and significant, almost delicate instances of emotion and meaning. His work seemed more like a comics equivalent to poetry than anything that had come before it and perhaps since, and Craghead used it to explore some wonderfully nuanced notions about the passage of time and human longing. In 2000, Craghead began to shift from comics and cartoon-based stories to projects more heavily dependent on non-iconographic drawing. Through works like

Thickets and

A Map's Little Spell, Craghead began to forge connections between the gallery world and the Internet and self-publishing that in some location suspended between them seemed to give his work a home and greater context.

His latest works have begun to make good on the staggering promise of those early mini-comics. An adaptation of young writer Erin Pringle's story "The Only Child" was nominated for a Pushcart Prize, while

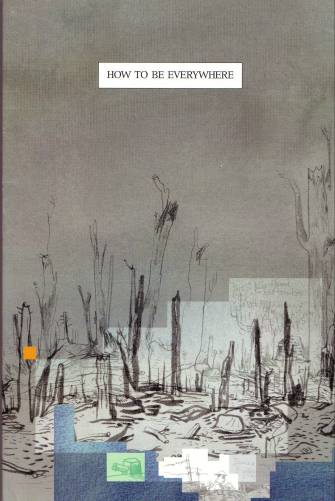

HOW TO BE EVERYWHERE [caps Craghead's] showcases the artist's almost unique ability to empathize with another person's view of the world by giving life to their words through their careful placement vis-a-vis a visual element: in this case, the words of poet and painter Guillaume Apollinaire. Rather than cutting into Apollinaire's poetry, dissecting its meanings, Craghead climbs inside of its causes and attending worldview so that in the course his interpretations explain, embody and ultimately reinforce the ideas behind the originals.

As a comics fan, you owe yourself some time spent with Warren Craghead's work.

Mr. Craghead has prepared

a special preview page for his latest book just for this interview. Thanks, Warren!

*****

TOM SPURGEON: Warren, I'm kind of unclear on what you do now. You mentioned a day job... are you making art full time?

WARREN CRAGHEAD: My wife and two-year old daughter and I live in

Charlottesville, Virginia, about two hours south of

Washington, DC, and an hour west of

Richmond. We originally came here because of my wife's job, but have decided to stay for a while at least. There's a surprisingly large art scene here.

For my day job I do design and art direction for a company based in North Carolina. I work alone in my office downtown which is also my art studio, so I'm able to deal with both sets of things throughout the day. Between that and some nights and weekends I get a good amount of studio time, but it's never enough.

SPURGEON: Can you tell me about your collaboration with Erin Pringle on "The Only Child" and how it came about?

SPURGEON: Can you tell me about your collaboration with Erin Pringle on "The Only Child" and how it came about?

CRAGHEAD: The literary magazine

Barrelhouse approached me for this project. In every issue they have an "illustrated story" where an artist chooses a piece they have accepted but haven't published yet. So I chose Pringle's short and creepy story "The Only Child" and got to work drawing it. It's not technically a collaboration because I worked off of the finished story with no input from her and luckily she ended up liking what I had done with her work.

SPURGEON: How do you look on your adaptation now that there's been some time since it was done?

CRAGHEAD: I really enjoyed making

that piece. I wanted to make something that both mirrored her story but also set up some parallel narratives, like visual grace notes to her main story. Making it, and trying to do her story justice, involved a lot of research and some very close reading which allowed me to find more and more in the page and a half story she wrote. That page and a half ended up as twenty pages for me because of the way I wanted to make rhythm in how I broke up her text. I was also aware that this was going to be published in a magazine that had curious readers but ones not used to strange comics experimentations, so I drew it in a clearer and at times very "normal comics" way. Well, "normal" for me anyway. I even quoted

Charles Schulz by using a tiny

Charlie Brown-like character in it.

A main undercurrent of

Pringle's story is death -- the story takes place in a hospital morgue -- so I found as many ways as I could to show death in a wide variety of symbols. I think my favorite page is the one where a drawer is open and it contains a flag at half-mast, then it closes, then it's open again and it has a dead tree. What I drew followed the text -- "We shut her drawer. We open it." -- but also referred to death and the crazy way the narrator is understanding everything. All that wrapped up in a visually jarring and, I hope, compelling series of images. The trick in comics is to make a picture that says several things at once.

SPURGEON: How many similar works have you done at this point?

CRAGHEAD: Other than "The Only Child" I've done two books with the writer

Roger Noyes [

Other People's Schemes and

The Problem With Chemistry], a book with Marc Geddes [

Wallball], two swapped stories with

Ted May [

Deliverance and

The Legend of the Prowling Paw] and

HOW TO BE EVERYWHERE which is drawings based on the work of the poet

Guillaume Apollinaire. I'm also working on three different "drawing conversations" with three artists which will eventually become individual books. Along with that I'm doing two drawing/video projects with people, and one other drawing/writing collaboration. It's a lot, but they all move slowly...

SPURGEON: Has working with people changed the way you approach your own work?

CRAGHEAD: Working with someone else, or with someone else's work, makes me do a lot of things differently. As I mentioned earlier, it makes for some very close reading as I really try to do right by whatever I'm working with. Working with Ted May's script for "Deliverance" was hard because I could see that really funny story drawn by him and I knew I couldn't match his comedic chops, so I had to go in another direction. Noyes' poems also threw me for a loop because I had to find things to draw in his poems without merely illustrating them. For the Apollinaire book I was trying to connect with not just his poems, but his biography and the whole world of pre-WWI Paris as well.

All this friendliness has affected my own work in a few ways. I'm more apt to steal -- I mean learn -- from people. I'm also finding I like having a fixed point to push against. Sometimes, by having someone else's work, work that I really respect, to go from I can seem to go farther out than if I was making all of it.

SPURGEON: How exactly did you discover Guillaume Apollinaire?

SPURGEON: How exactly did you discover Guillaume Apollinaire?

CRAGHEAD: I came across Apollinaire as a result of my long interest in

Cubism which has been a steady influence in my work for a long time. Apollinaire was a great champion of

Picasso and

Braque and other leading edge

avant garde artists in pre-WWI Paris -- reading his work one can really see and feel the crazy energy of that time. He saw poets and artists as heroic and seers, as badasses. That and his embrace of the changing world around him was very appealing to me. I should also mention he was the first poet to seriously make "concrete poetry" where the way the type is laid out on the page forms an image that interacts with the text of the poem itself -- he called them "calligrammes."

At the same time I was interested in the intersection of words and images and specifically how poetry could be used with pictures to make something else. I started this project around the time I published

Jefferson Forest and

thickets which are along those lines. The drawings that became

HOW TO BE EVERYWHERE started as just little exercises in my sketchbook, little scrambles of Apollinaire's words with some of my drawing.

SPURGEON: Were there specific qualities in his work that led you to want to explore it?

CRAGHEAD: Well, his work is full of great images, and the language is also startling and beautiful, especially

the Donald Revell translations. Beyond that I'd say it's his deep affection for the world around him, the changing world of

avant garde Paris, and how he tries to reflect that world while holding onto valuable methods, techniques and aesthetic tricks from the past. He uses beauty which makes his work powerful and compelling. That use of optimism and beauty was probably easier before WWI, but his later work, after he had fought in the trenches and almost died there, still has that spark.

Another thing I saw is his relationship to the visual art revolution going on around him. I think there's a lot we can still learn and steal from those Cubist paintings, especially those of us looking for new ways to tell stories using pictures.

SPURGEON: Can you talk about the show that preceded the book? How does the fact that this material was in a show have an effect on what we see on the printed page?

SPURGEON: Can you talk about the show that preceded the book? How does the fact that this material was in a show have an effect on what we see on the printed page?

CRAGHEAD: The book preceded the show, part of it by several years.

SPURGEON: My bad. How did it develop, then?

CRAGHEAD: I started the drawings that became the book while I lived in

Albany, New York -- my wife was in school and I would go to the library with her. She studied while I drew and ransacked the university libraries for images of France, Paris, WWI, etc. I laid that group of work aside for a few years and came back to it when Gallery Neptune in Bethesda, MD offered me a show coinciding with the

Bethesda Literary Festival. I decided to finally finish the book and make some accompanying drawing/collages.

The book and its drawings influenced the wall pieces a lot -- bits of each are in the other. The wall pieces were colorful collages on board, all 12" x 12". They also were each based on a single poem rather than using fragments and lines like the book drawings. The car I drew for the book also ended up in the collage based on that poem ("Le Petit Auto"). I had originally planned on also showing the drawn pages of the book in the show, but that didn't work out.

The book itself was affected very little by being in the gallery show. The numbering of the books was something I hadn't done before, but other than that it was the same as if I had just published it.

SPURGEON: Did you have a general notion of how you wanted the work interpreted in this visual-verbal way and then figured out how to apply that to each piece, or did you struggle through each individual piece? Was there a key?

CRAGHEAD:

CRAGHEAD: At first each page was done separately. I would draw something, then find an appropriate piece of a poem to add into it, then draw some more, revise the text, and on and on. At times I started with the text, but usually it was the image first.

As the project grew I started deliberately doing pages to fill holes -- I tried to follow Apollinaire's life in the work with a rough Paris section at the start followed by bits of his war years. The final composition was in ordering the pages. I laid them all out in my living room and moved them all around. I was looking for a balance between the flow of images and text and some structure loosely based on his life. The final few pages were really important to me - some of his final poems sum up his whole enterprise and I wanted to reflect that.

So no, there is no "key," no master unlocking secret to all the pages that allows one to read them. I did use some of his symbology (as well as a bit of my own), but each page stands on its own inside the larger flow of the whole book.

SPURGEON: Is there possible to see in the work any antecedents? Saul Steinberg springs to mind as a potential cartooning influence here, was he? Were there other cartoonists? Other artists?

CRAGHEAD: Saul Steinberg is someone I look at a lot. He can pack narratives and ideas into seemingly simple drawings, and that multivalent image-making is something I'm very interested in exploring.

Raymond Pettibon is another word and picture scrambler I look at, though my favorite pieces of his are from old Minutemen LPs I bought as a youth. His work needs both the words and the images -- either alone is much less than both together, and than kind of friction is something I wanted to make happen in

HTBE.

Gary Panter's crazy and ambitious remaking of

the Divine Comedy is another thing I look at a lot. He keeps the story very Panter, but injects lots of parallels with

Dante and other writers.

One other antecedent, though I know it's way above my weight class, is

James Joyce's Ulysses which, on one of its almost endless levels, uses the Odyssey as a rough template. Like Panter, that absorption of an older thing into a newer piece is something I'm interested in.

SPURGEON: I wanted to ask about a couple of your basic approaches. The first being the diagrammed-out pictures, where there are actually lines between objects and words playing different roles at the end of these paths than they might down their length. The second is the kind of layered shapes effect you get that sort of look like some 20th century painting.

SPURGEON: I wanted to ask about a couple of your basic approaches. The first being the diagrammed-out pictures, where there are actually lines between objects and words playing different roles at the end of these paths than they might down their length. The second is the kind of layered shapes effect you get that sort of look like some 20th century painting.

CRAGHEAD: I think comics and narrative storytelling can learn -- and steal -- a lot from both information design and from

Modernist, specially Cubist, painting. The diagrammatic pages are directly from my interest in how story and information can be delivered in different ways. The lines link the word with the pictures, as in a real diagram, but the connection between the two isn't always on the surface. The images and words also start getting mixed up with each other, scrambled, making something destabilized and a little confusing, which can open the readers eyes up to an experience of seeing the page rather than just reading it.

The layered shapes, and the references to Cubist and related Modernist artwork in general, comes from Apollinare's deep interest and enthusiasm for that work. It also comes from my thoughts about how the lessons of Cubism can be applied to comics and narrative storytelling. I'm just beginning to work on this, but I think there's something to investigate there and the parts of

HTBE that go there are just the first steps.

SPURGEON: What are your expectations for an audience? Where does a book like this sell?

CRAGHEAD: I know that there's only a small subset of the comics world that is interested in something like this. It's poetry -- French poetry! -- it's weird drawing and it doesn't use most of the usual conventions of comics... Still, I think anyone can read it and get things out of it -- it rewards close reading. It's for sale at some online places [

Cafe Royal in the UK and

Little Paper Planes in L.A.] and is also available through my galleries in DC [

Gallery Neptune] and Richmond, VA [

ADA Gallery] and also at a local store here in Charlottesville,

Destination Comics. I've also sold some directly over email. I'm exploring publishing it in France and I may issue a second edition when this one sells out.

SPURGEON: Do the pages with some of the poems included within them generally include all of the poems, or are there substitutes made in terms of visual information for words? How did you approach the issue of whether or not to include words?

SPURGEON: Do the pages with some of the poems included within them generally include all of the poems, or are there substitutes made in terms of visual information for words? How did you approach the issue of whether or not to include words?

CRAGHEAD: I took chunks of his work -- only two pages have complete poems. I didn't drop words out and replace them with images, but at times the images do function as words or letters, building on each other in a logical progression like letters forming words. The images and Apollinaire's words need each other in my book. I was making a friction between them that would hopefully, while still referring to the old things, make something new.

SPURGEON: Is there anything you discovered about Apollinaire's work in the process of working with it that you didn't know before?

CRAGHEAD: A big thing I discovered is his rich and deep affection for the world, for the stuff and materials and people around him. He's like Walt Whitman in that way, and, like the Cubists who led me to him, he always grounds whatever crazy flights he takes with the real, concrete things around him. I try to learn from that, to look at my work and ask, "Is this real? Is this close to a true experience?" and "How do I make something that

is an experience, not merely something that points to one?"

SPURGEON: Is there any other cartoonist out there you'd like to see approach adaptation? Who? Doing who? Is it something you wish to continue pursuing?

CRAGHEAD: Adaptation is a rich land for us artists to plunder. Seeing Panter's Divine Comedy adaptation showed me how on can work from a text but make it completely one's own.

The drawn version of Paul Auster's City of Glass that

Paul Karasik and

David Mazzuchelli made is another example of an adapted story that uses the friction of words and pictures to make something that runs parallel to the original text.

David Lasky's

Ulysses adaptation is another great piece. I do want to continue mining this vein -- there's one poetry project in particular that might take me the rest of my life, but I'm a little leery of it. There's also another French poetry project in the works.

If I could command people to do adaptations, I would order Ted May to do

Kurt Vonnegut, Jr., Crumb to do

John Ashbery's Girls On The Run (which is Ashbery's poetry version of

Henry Darger's drawings), and

Kevin Huizenga to do

Paradise Lost. I guess I'd also want to see

Gilbert Hernandez do

One Hundred Years of Solitude, but it's really unnecessary since his

Palomar is as rich and alive as

Marquez's Macondo.

SPURGEON: How much of a connection do you feel with Apollinaire's desire to match old forms and new? What is the purpose of doing so, do you think, for Apollinaire? Was it a goal in and of itself? Was it a way to better represent life or a political moment?

CRAGHEAD: I feel a great connection with the old/new aspect of Apollinaire's project. I hope my experiments and wanderings are like his - ones that are deliberate attempts to more closely render our experience of the world. Apollinaire was seeing so much change in his world that he knew the old forms just couldn't keep up and I see that now too. In art, and especially in comics, I see a lot of wide open territory.

SPURGEON: How would you describe the satisfaction you get out of work your very idiosyncratic corner of the comics world?

SPURGEON: How would you describe the satisfaction you get out of work your very idiosyncratic corner of the comics world?

CRAGHEAD: The satisfaction I get from my work is both the process of making and the finished piece - seeing something I've made that baffles and confounds me. Something that stays mysterious. I'm not getting rich or famous, but I am finding new things all the time. Another satisfaction is the reaction I get from people and when I see others working along the same lines, artists like

Andrei Molotiu and

Gary Sullivan. That tells me we're on to something.

SPURGEON: Tell me about the rest of your 2007.

CRAGHEAD: With a crazy-drawing two-year-old daughter I'm busy without picking up a pencil, but I do have some stuff lined up. For printed work I have an 11-page piece in the recently released UK book

Cafe Royal [issue zero], edited by

Craig Atkinson. For that one I made three small tear-out and DIY booklets that all add up to a kind of autobiography. I'm not sure when it prints, but I've done a 4-page color piece for the next

Rosetta from

Alternative Comics. The pages from

HTBE will be in a show in Portugal as part of the

Amadora Comics Festival and there's a chance I may go see it. For art shows, I'm in a group shows in Washington DC, Pittsburgh and New York this fall, at least one of which will have an online component.

*****

all art from Mr. Craghead's new book, except for images #2-3, which are from his adaptation of Erin Pringle's "The Only Child"

*****

How To Be Everywhere, Warren Craghead, Warren Craghead and Gallery Neptune, soft cover, 100 pages.

Special Preview.

*****

posted 10:30 pm PST

posted 10:30 pm PST |

Permalink

Daily Blog Archives

November 2019

October 2019

September 2019

August 2019

July 2019

Full Archives