December 30, 2013

CR Holiday Interview #13—Ed Piskor

CR Holiday Interview #13—Ed Piskor

*****

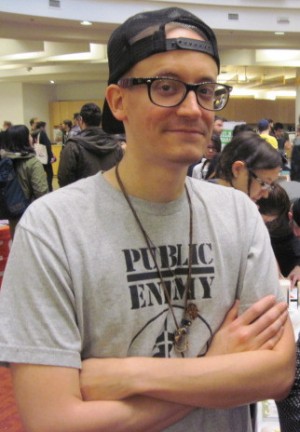

It's my great pleasure to end posting at

CR for the year by running an interview the cartoonist

Ed Piskor. Piskor is one of a thriving group of Pittsburgh-area cartoonists that have become a frequent presence at comics shows east of the Mississippi. He's a comics lifer: first a fan, then a maker of comics like those he was reading with ambitions of comics stardom, then briefly a student at

the Kubert School, then a mini-comics maker, then an artist that caught the eye of

Harvey Pekar, then a working cartoonist writing his own material again and slowly building an audience through works like the phone-phreak driven

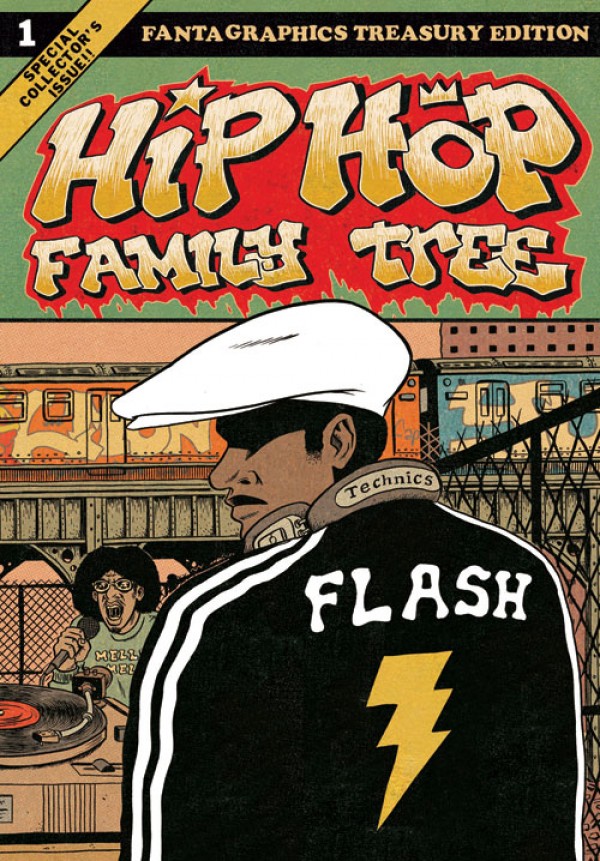

Wizzywig. Piskor's latest project is

Hip Hop Family Tree, a history of the sub-culture that focuses on the small sprawl of neighborhoods and interlocking relationships which changed American pop expression. His publisher is

Fantagraphics. I always enjoy talking to Ed and was happy to get a chance to ask him about this latest work, one of the defining releases of 2013. -- Tom Spurgeon

*****

TOM SPURGEON: A real basic kind of opening question: where are you with the cycle of Hip Hop Family Tree

Vol. 1, Ed? I'm guessing you're still doing publicity right now. You've traveled a little bit for it, I think; where are you right now in what you have to do to get word of your book out there?

ED PISKOR: We sold out of the first printing. It sold out before... I guess the way

Diamond works is that it takes two weeks for a book to hit every store that Diamond distributes to. Two days after the first batch of stores got their comics, the Friday of that first week, they called Fantagraphics and said we needed to print more. So it's doing good, man. For a couple of months, starting in September with

SPX, I did a lot of traveling, every weekend going to different book festivals, arts festivals...

I spoke at this symposium in Chicago that had Buzz Aldrin giving speeches.

SPURGEON: That's right. I saw that.

PISKOR: The comic has opened up a lot of cool opportunities outside of the comics microcosm, which has been pretty cool.

Right now -- at this very moment -- I'm inking the last two pages of book two.

SPURGEON: So you're that far ahead. Now, you're devoted to a yearly cycle with this series, am I right?

PISKOR:

PISKOR: Pretty much. The second book should come out for

San Diego Comic-Con. I had the first book almost complete by the time I decided on Fantagraphics as the publisher. So I was already pretty done with that. It's going to stabilize into being an annual thing for a while.

SPURGEON: I heard that you're contracted for multiple books, but I also heard that maybe you don't know how many books the series will be. Someone told me that you're sort of feeling your way through the books, and don't know how many books the whole thing may encompass. The idea is that you don't know yet what you'll end up spending a lot of time on, that once you get into something, that pay mean an extra four pages here, and extra six pages there, and that this could add up. Is that a fair assessment? Or do you have a firmer idea now of exactly where you're going.

PISKOR: With each book I don't have a map of where it's going to end, but I know all the key points that need to be covered. Each book is going to be roughly the same page count: about 112 pages apiece. When the first book was winding down, the last 20 pages or so, I started seeing a very clear place of where it should end. That's also been the case with book two. So I think that's how it will end up being.

I'm signed up for six books with Fantagraphics. And if I'm still into it... this project is a part of my five-year plan. After that point we can assess. Hopefully sales will still be strong enough to warrant continuing to do it, but it's really cool -- I'm in a sweet spot right now. I'm doing the exact comic I want to, and it's working out.

SPURGEON: Have they been a good publishing partner for you? Your public reputation is of someone who knows what they want and how you want it done. I assume they've been a good partner in terms of staying hands-off and facilitating your doing what you want to do with the project.

PISKOR: They're hands-on when they need to be. They're super-receptive to other parts of the process more related to business things. Like very early on -- I put the strip up once a week on

Boing Boing. That's millions of readers a month. That's not to say millions of people read my comic, but I bet tens of thousands do. The site is not really built for comics to be read in a serial way. That space is almost like a billboard for the actual book. I told the guys at Fanta, "Listen, we have to make this book available for pre-order as soon as possible. Every week I put this strip up without the book being available for pre-order, I feel like we're leaving money on the table. This is a valuable opportunity." People pay money for that kind of advertising space. They listened.

Mike Baehr at one point said it was the most pre-ordered book they had on-line ever, by like a multitude. It's cool that they listened to that stuff. They have good suggestions here and there, too. So it's been real great.

SPURGEON: I'm not going to stick to business for the entire interview, I promise. But you're just past the age of 30... I think that's an age when artists in all media start to really pay close attention to what they're going to do in the medium they chose. At 30, you're usually no longer just taking whatever comes to you when it comes to you. There's an active thought process of your own, an idea of what you want to see happen. I wonder if that is true of you, and I wonder if that is true of you and this book. This seems like a very ambitious project, Ed, something in which you're very invested. You see yourself settling into projects like this from now on, or is there still going to be an element of winging it?

PISKOR: This project in particular... this is a comic I want to do. I want to see it through. It's a chunk of good fortune that people are responding well to it. I think I would still do it anyhow.

I have to make this stuff work for me. So I'm very conscious of the business part of it. I can't just do exactly what I want to. By the way, to go with Fanta was a little bit of a gamble. I had some other publishers that were interested, and I could have made more up front money doing that. I had a very specific idea of how I wanted it to look to create the experience I wanted. It had to be this big, over-sized treasury format. That was a no-go for a lot of publishers. I have these yellowed pages to go with the artwork; a lot of the publishers wanted to drop that background layer and leave the pages white. That would destroy -- the color is based on that yellow. There were all these problems that were mitigated just by going with Fanta. I am invested in this project in particular. Whatever I involve myself in I'm going to be invested in it.

SPURGEON: We both know there's a fine line in comics. We both know people that don't have a ton to offer in terms of the comic, but they're extremely business-like. We also know folks with a lot to offer in terms of the comics they make, but are constantly getting in their own way. It seems like it's tough to find that balance in comics: letting your artistic impulses drive the car, but be open to hearing from the business-minded guy in the passenger seat. You've been around long enough to see people fail for all sorts of reasons.

PISKOR: For sure. If there's one thing that I've discovered meeting cartoonists, and even cartoonists I would call my heroes, I learned and realized that a lot of people are their own worst enemy and they create their own glass ceilings and stuff like that. It's all this logic and they have these personal, limited beliefs that create barriers to what they do. So realizing those sticking points, seeing them in other people, I'm just trying to take care of that so as to not inhibit what's possible.

SPURGEON: You're actually younger than hip-hop. So by the time you were aware of it, it must have been ubiquitous. You can't remember a time hip-hop wasn't around.

PISKOR: That's correct.

SPURGEON: I imagine that's true of comics, too, of course. They were around as well. But hip-hop... the book has this unique take on the role of scene

. It's very generous and solicitous towards the regional aspects of hip-hop's creation. But since your memory of hip-hop was shaped by it having gone national, I wonder how you started thinking about hip-hop so that it became this expression of something that happened in those specific East Coast communities. Do you remember when you started to have that kind of interest, this specific conception of cultural history? Do you remember your initial curiosity?

PISKOR: Yeah, I do. It started with getting what was popular at the time. You would hear older rap records being sampled -- a line or a beat or something like that. It sort of hit the same compulsive tendencies that I had as a kid reading comic books, before I really cared about creators and stuff. It was about the stories and whatever else in mainstream comics. I would dig around looking for old comic books, like the first appearance of Cable from

X-Force. Whatever. To find Dr. Dre's first record digging in record crates and talking to people, asking around in record stores, it hit that same compulsion. Then when you dig very deep and learn about the earliest people, I feel like I'm on some of the same footing as some of those guys. I come from poor circumstances and stuff like that... it's an inspiring story to see someone come from under the radar, to see these people do cool, creative stuff.

SPURGEON: What's fascinating about the history as you choose to portray it is that it's almost week to week and apartment to apartment and party to party and neighborhood to neighborhood in its specificity. It's very graspable, too. That was something I loved when I learned about comics, that comics history wasn't that old -- you could go to conventions and see the guys that were there at the beginning. So was having that grasp of it, wast that exciting to you, being able to grasp the entirety of it?

SPURGEON: What's fascinating about the history as you choose to portray it is that it's almost week to week and apartment to apartment and party to party and neighborhood to neighborhood in its specificity. It's very graspable, too. That was something I loved when I learned about comics, that comics history wasn't that old -- you could go to conventions and see the guys that were there at the beginning. So was having that grasp of it, wast that exciting to you, being able to grasp the entirety of it?

PISKOR: Yeah. It is cool. It is cool. If you think about what we know of rap and of hip-hop, it started in a very confined space. Everybody knew everybody. It's the same for comics as well. Distribution. The distributors are the gatekeepers, so you have to know somebody that knows somebody to get something to happen. You read about the history of comics or the history of rap and you see that there are all these relationships that were required to get it to the point where it is right now. There were almost no rap records being put out outside of New York and New Jersey -- the part of the New Jersey that

Sugarhill was from was right over a bridge. Everybody in those early days, for the first 15 years, had a relationship to each other. It's fun to explore how these weird circumstances built upon themselves to create this kind of phenomenon.

Reading about that history there are other kinds of music that come into vogue and quickly disappear that people don't talk about anymore. These are things that could have been the next hip-hop if certain situations took place. I'm talking about

house music, or Washington D.C.'s

Go-go music. Those things are still around but they're not at the scale rap music grew to, and they came around the same time.

SPURGEON: You have talked about trying to double-source the incidents you depict, and you've actually complimented what you feel are pretty solid sources upon which you can draw. Is there any sorting process... did you have to make any decisions as to what you believed was real at any point, or is there pretty much an orthodoxy when it comes to this specific cultural history?

PISKOR: There are situations that come up where there might be an exciting, visually interesting narrative conjured up out of the mouth of one or two of the people that were part of the situation.

SPURGEON: What would be an example of that? Is there something in the book kind of like that?

PISKOR: This is from book two:

KRS-One's origin. He talked about being kicked out of the house. His family was poor and he at the last bit of food that was supposed to be for their dinner. He got kicked out and never went back. You can't reference... there's nothing else to reference but his words. There are tools in comics were you can take his words and you can make sure they're not your words. You can take those words and put them in his mouth, make it a story from his point of view and use captions that say things like "As the legend goes..." or something like that. You make sure that if it is some mythological thing you separate yourself from that. I'm very conscious of that kind of thing. As more rappers get in touch and tell me some crazy stuff and I can't find source material, that's how I'm going to approach it. I'm going to put it "In the words of..." There's a running dialogue in captions throughout the book, so when you switch that up you hope the reader picks up on that.

SPURGEON: People become accustomed to your rigor.

SPURGEON: People become accustomed to your rigor.

PISKOR: When you use a different storytelling device, I hope that it creates a feeling that it's not me saying this

per se. Doing this stuff on

Boing Boing -- and I'm sure you know this from your site -- people are happy to let you know when you've done something wrong. [Spurgeon laughs] I've created all of these contingency plans. Ways to prevent damage, if there's something I'm not fully convinced might be 100 percent accurate because I can't find more source material.

SPURGEON: Were there any roads not taken? Did you consider doing one individual's story as a different way of structuring the book? One of the things that's really intriguing about this book is how fiercely scene-oriented and community-focused it is. There's this run of personality after personality after personality. Did you ever think of focusing your history, perhaps doing one person? What was the appeal of making it this broad and comprehensive of a history?

PISKOR: The appeal of doing the broad scope thing was really because of the regional nature of hip-hop's origins; I'm really fascinated by how everyone had a relationship with each other. I considered doing just a biographical comic. Even with

Wizzywig, it started out as a biography. But my popularity, and with comics in general... I think people don't respect comics or me as a creator.

To do a biography in comics you have to have access to the person -- at least as far I'm concerned. You have to be able to work with them. There were no takers. In the hacker world I approached people. I had only done a little bit of stuff for Harvey Pekar at this time, so I don't fault them -- in fact, I'm friends with a lot of these people -- but they wouldn't even respond. I had no idea how to even approach a rapper to try and tell us a specific story. In the end, I think this was the way to go. It's like the character in my comic is hip-hop. It's a biography of hip-hop and everybody is a cog in the wheel that helped created this thing.

SPURGEON: Did you think of another fictionalized account?

PISKOR: For a long time, even since high school, I've been wanting to do a comic with this kind of imagery. I love hip-hop fashion, I love graffiti, I love '70s New York films --

Scorsese films,

French Connection,

[Taking Of] Pelham 1-2-3 -- it just has that grit. I always wanted to do something in that landscape. A fictionalized account. I was thinking I could do a crime story set in this world. Ultimately, I felt like this was the way to go.

By the way, I had no idea, and I still have no idea, if what I'm doing is like, illegal. You know? [Spurgeon laughs] I have no clue. It's literally something I wanted to do. I was surprised that

Boing Boing said it was okay to publish. I'm surprised Fantagraphics said it was cool. Does that mean somebody could do a comic about me? That feels invasive.

SPURGEON: Maybe someone will get their revenge by doing a comic about you doing this comic... Ed, I'm also interested in the visual sourcing aspects of your research. Did you spend time in these neighborhoods? Would that even work at this point? Did someone take photos of that time period?

PISKOR: There were a few great photographers that really captured that scene. I'm not even sure they consider themselves... at the time I don't even know if they considered themselves photographers or if they knew what the heck they were doing or how important they were in capturing the birth of this culture. There was a photographer named

Joe Conzo -- still, he's not a professional photographer. He's a New York City fireman. He had a camera in those early days, and shot film at these live performances and block parties. I have access to some great photographs from that period. Another photographer named

Martha Cooper... when graffiti started to catch on, she saw value in that and started capturing photos of that stuff. She really captured that New York landscape in a beautiful way. There's hyperbole in the work, too, and that comes from my love of the films I mentioned earlier. That's sort of the soup my work was created out of. There a few good hip-hop flicks. There's

Style Wars and

Wild Style that helped give me visual cues.

SPURGEON: This is a hunch on my part, but I liked the way you didn't aggressively pursue a comics solution for the music. When people do comics about music, there tends to be a dramatic choice on how to portray the work being done in that medium -- you portray the performances and the art itself in a very matter of fact style. There's not a big shift -- you can't flip through the book and easily pick out the performance pages. There's no trickery in portraying the art involved. Is that on purpose? Did you want to portray the music in this matter-of-fact way rather than making a case for it.

SPURGEON: This is a hunch on my part, but I liked the way you didn't aggressively pursue a comics solution for the music. When people do comics about music, there tends to be a dramatic choice on how to portray the work being done in that medium -- you portray the performances and the art itself in a very matter of fact style. There's not a big shift -- you can't flip through the book and easily pick out the performance pages. There's no trickery in portraying the art involved. Is that on purpose? Did you want to portray the music in this matter-of-fact way rather than making a case for it.

PISKOR: The way that I see this comic is that it's not a music comic. It's about community. It's about these people that had some ingenuity meeting each other, putting together these ideas, building off the existing ideas, and creating this big thing. It has almost nothing to do with rap. Rap is a byproduct. It's all of these people coming together to make this big thing. The music part of it is simply a byproduct of the story, the narrative taking place.

Right now, a strip I just submitted is that

Run-DMC went to the West Coast for the first time. They're basically nobodies, so they're playing this club. Two guys who work at the club are

DJ Yella and a very young

Dr. Dre -- Dre and Yella go on to form

NWA and then Dr. Dre goes on to do his own thing. He discovers

Eminem. This performance set Dre towards more of a street-level style as opposed to trying to be like

Prince or

Michael Jackson -- which is what he was doing at the time. He had on scrubs and a surgical mask. So that's what this comic is: how these guys inspired each other and weird business things that happened, just that kind of stuff. Music is almost negligible.

SPURGEON: Are there scenes in there you were really looking forward to doing? I think in this book one of the scenes you take some time with is a famous one with Kool Moe Dee and -- I always forget the other guy's name because I think of Kool Moe Dee feuding with LL Cool J but that's later than this. It's Kool Moe Dee's beatdown of...

SPURGEON: Are there scenes in there you were really looking forward to doing? I think in this book one of the scenes you take some time with is a famous one with Kool Moe Dee and -- I always forget the other guy's name because I think of Kool Moe Dee feuding with LL Cool J but that's later than this. It's Kool Moe Dee's beatdown of...

PISKOR: Busy Bee.

SPURGEON: Right. That's a famous enough incident that when it was happening in your book I sort of remembered it as part of the lore of that world, as a famous incident. Were there scenes like that that you looked forward to doing because they were pivotal scenes.

PISKOR: Yeah, for sure. There are still a lot of scenes I'm looking forward to portraying in a big way. I consider that a paradigm shifting moment.

In book two, there's like ten pages or 12 pages devoted to the movie

Wild Style. That was a very important movie in terms of propagating a style. Just as a fan, I remember hearing about

Wild Style and how important it was for the culture. Then I saw it, and I didn't recognize anybody in the movie except for

Fab 5 Freddy and

Grandmaster Flash. So I had a million questions in my head. "If this is so important, then who the hell are these people?" [Spurgeon laughs] "What is this. What gives them the right to even be in this important movie?" I want to answer the questions you might have once you see

Wild Style. A couple of times this year -- it was

Wild Style's 30th anniversary. I opened it up in a local theater and had a 30 minute talk. I introduced the film and who the people are and who helped them make the flick. When situations happen that are paradigm shifting or are on a bigger level for publicizing the culture outside of New York, it really deserves extra attention in the comic. Maybe just a couple of pages, but however long it takes to present the relevance of a situation and its importance.

SPURGEON: You mentioned Fab 5 Freddy. Keith Haring is in there. Jean-Michel Basquiat. So you have the wider New York art scenes... the New York arts world more generally, with Debbie Harry in there -- she would of course contributed to the popularity of hip-hop culture. Was it important to you to include these other arts figure because of their importance in how that culture was transferred? You could argue that people like that weren't involved in the core scene.

SPURGEON: You mentioned Fab 5 Freddy. Keith Haring is in there. Jean-Michel Basquiat. So you have the wider New York art scenes... the New York arts world more generally, with Debbie Harry in there -- she would of course contributed to the popularity of hip-hop culture. Was it important to you to include these other arts figure because of their importance in how that culture was transferred? You could argue that people like that weren't involved in the core scene.

PISKOR: It makes more sense in Book Two. I'm talking about hip-hop culture as four elements that include graffiti art. Graffiti is the first element of hip-hop that was able to be monetized. So in the earliest '80s, graffiti started to invade downtown art galleries in Manhattan. Keith Haring was a graffiti artist. Basquiat: graffiti artist. It was when they were brought downtown and selling these paintings -- making excellent money by the way -- as a companion piece to these art shows, they would bring the guys from the Bronx, they would bring

Afrika Bambaataa to play in these galleries. They would bring the break dancers. The whole thing.

The byproduct is that these scared white people didn't have to go to the Bronx to see this happen. These scared white people are people who might be producers of

20/20, the magazine show. They might write for

Rolling Stone. They might write for the

New York Times. They didn't have to to into treacherous territory to see this stuff happen. It was right there in their face. More opportunities about once they were on the radar of the bourgeois -- the art crowd, whatever you want to call it. Their inclusion is very important. Basquiat produced a rap record that's the most valuable rap record in history because of its artwork. It's like the cheapest Basquiat print you can get and the most expensive rap record. He deserves to be mentioned in the book.

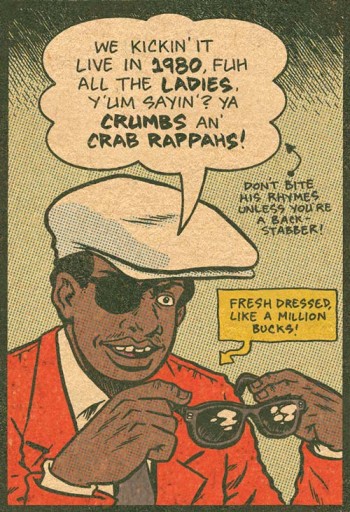

SPURGEON: You mention Afrika Bambaataa. Your design on him is very striking. Russell Simmons is portrayed in much the same way -- there are outsized, cartoony elements to them. Was it fun to do that with some of the characters. We talked about photo reference a little bit, and this seems like something totally different. Was that fun to work out the look of each one -- the visual signifiers? Were there things you wanted to do with the look of certain people.

SPURGEON: You mention Afrika Bambaataa. Your design on him is very striking. Russell Simmons is portrayed in much the same way -- there are outsized, cartoony elements to them. Was it fun to do that with some of the characters. We talked about photo reference a little bit, and this seems like something totally different. Was that fun to work out the look of each one -- the visual signifiers? Were there things you wanted to do with the look of certain people.

PISKOR: Yeah it's really fun. There's a lot to consider an a lot to juggle. With the iconography of comics, you can really screw things up and confuse people. You have to figure those things out. The different resources I used in comics to make sense of this huge ensemble cast, it would be things like

Chris Claremont's

X-Men or

Larry Hama's

GI Joe comics, how you can have a cast of hundreds of people. You have to have some shorthand visuals so that people are like "Oh, who is this person again?" Part of it is you want to capture personality, but I like to lock myself into costumes with these people. Per era.

As another instance, this page I'm looking at right now, Dr. Dre with his surgical mask on. I draw him with the respirator and the doctor's outfit and the fake gloves so you can immediately see it is Dr. Dre. He would wear that costume for real, so it's like let's keep him in it at all times. It's also comedic, because he's out on the street. There's no scene like that in here with him like that -- you can imagine him against the background of other buildings in his doctor's scrubs. It's kind of funny.

SPURGEON: I want to ask you some comics questions to wrap things up. When I think about guys that worked with Harvey Pekar, and when I think of your comics, I think of a baseline clarity; they seem to be very direct. Hip Hop Family Tree

seems like it would be a tremendous challenge to that, that it would be difficult to convey all the information you want to convey while keeping things moving. It's a staggering amount of information this narrative. Was that a special concern, just to make sure what needed to be gotten across got across page to page to page? Was there any working over of certain scenes, perhaps reducing what information would be shared for the sake of clarity? What were the challenges there?

PISKOR: There aren't a lot of challenges to it, because I'm giving myself a lot of personal rules and deadlines -- that helps me keep on track. Part of the aesthetic of those old comics was deadline-oriented, so I want to keep that spirit. So you have to make choices; the choices I've been making are more like life choices. I'm definitely hanging out with friends a lot less to make sure I have time to work on the strip. For each two-page strip, I spend an entire day reading material, thinking about it, playing around with ideas, etc., etc. For every two pages I try to pick things out, focus on the most visually appealing stuff -- or at least the most visually appealing way to get the information across -- and then spend the rest of the week executing the stuff.

Working with Harvey, there were certain... I didn't learn so much from him... what I learned from Harvey was basically the disciplinary stuff. "If you're going to work in comics, it takes a lot of work." We did

this book about the Beat Generation. One of the things that I took from that experience for this one is that Harvey chose a lot of good moments panel-to-panel wise. It's sort of the same format in the way of the storytelling, where there's not much panel to panel cause and effect, moment to moment interaction.

SPURGEON: They are definitely striking when it happens. You're right, it's not that way.

PISKOR: That's something I took from him. I've really developed a strong habit of comic-book making over the past nine years of doing stuff. I got into the game at 21. When I put pencil on paper with Harvey for the first time, that's when I hooked up with

Jim Rugg and

Tom Scioli. Jim was doing his first

Street Angel comics and Tom was doing stuff for

Image. Those guys are older than me; if I was 21, they were 26 or 27. That's a big gap.

SPURGEON: It is.

PISKOR: I was a real jerk-off. Having access to Jim and Tom has pushed my work five years ahead of where it might be not having them as friends. I see what it takes to be a cartoonist. Part of it is me just trying to stack up to them, live up to what they do. Did you ever read

the Malcolm Gladwell book bout outliers?

SPURGEON: Sure.

PISKOR: He talks about that there's a shocking percentage of

NHL all-stars that were all born in January because of some weird Canadian weird cut-off date to play hockey. They snuck in under the wire. They were younger than everyone else and they were smaller than everyone else. So they had to work ten times harder. I'm not saying I'm an all-star, I'm just saying I'm a young dude that have privileged access to these guys who turn out to be some of my favorite cartoonists working today. I see what it takes. It's been beaten into my head for a long time. The comic-book making part of it, there's a lot to consider, but it's never daunting. It's already a strong habit.

SPURGEON: What is the key element you find satisfying about doing comics? You talked in your interview with Marc Sobel about comics at one point having a therapeutic effect for you. When you were a young guy they were a way to get over some feelings of isolation that came after getting over some health issues. Comics was a way you processed your life. I always wonder after pleasure with cartoonists, though. You have talked about the fun of doing work set in this time period, so obviously you've thought about doing comics in terms of fun and enjoyment. But what is it for you: is it the process? Is it getting work done? Is it

SPURGEON: What is the key element you find satisfying about doing comics? You talked in your interview with Marc Sobel about comics at one point having a therapeutic effect for you. When you were a young guy they were a way to get over some feelings of isolation that came after getting over some health issues. Comics was a way you processed your life. I always wonder after pleasure with cartoonists, though. You have talked about the fun of doing work set in this time period, so obviously you've thought about doing comics in terms of fun and enjoyment. But what is it for you: is it the process? Is it getting work done? Is it having

work done? Is it getting to see it reflected back towards you when people read it? Do you like the time you spend cartooning? You seem so devoted.

PISKOR: I personally feel like I get a lot of rewards from doing comics. The actual process of making comics is so fun to me. It's probably the most fun I can have. I'm sure that people will look at this and go, "Oh, that's pathetic." [Spurgeon laughs] You can think that. But I do not bind myself to any societal standards at all. You can think I'm a loser; I'm having a freaking ball. I think about the times when I was a little kid really, really frustrated with myself that I couldn't draw something the way I wanted it to look. I still can't! But it's getting better. As a kid I kept drawing because I noticed the next time I drew something it would get a little bit closer... so I have this privileged opportunity of meeting goals. I set goals for myself and I accomplish them. There's a feeling to that I can't even explain to you. That's how it goes with the production stuff.

I'd be lying -- and by the way, I think all cartoonists who have publishers and who put stuff out into wide release, I think

they'd all be lying if they said they didn't want people to see the stuff and provide a reaction. That's cool, too. Positive and negative. The negative doesn't cramp my style. It either helps me to work harder, if it's negative feedback from somebody I respect, or if I think they're a douchebag I'm going to ramp things up ten times more to just kind of fuck with them. That's fun. Going to conventions and stuff... I've made some really, really great friends. You know from going to conventions, too, you'll see two people talking who are obviously and clearly strong friends in a really deep conversation and they could look like they're members of different tribes. I've been making friends I know I would otherwise never make because they would think that I'm an asshole or maybe I think they're a douchebag, just from the first visual reaction that you feel inside. Whatever that initial instinct is. So that's been really awesome, making cool friends over the years. I'm a lifer, Tom, and it's no joke. And there's all aspects of it I find enjoyable.

SPURGEON: I heard different cartoonists talk this Fall that basically said they developed style after failing to match the standard provided by a stylistic role model. Their own style was not being able to draw like their hero. Do you have ideals, are there signposts, are there people you wish you could draw like? Are you jealous of anyone's specific skill? Or are you really comfortable with what you do at this point.

PISKOR: I look at people's work a lot and try to see what I can steal from it. For myself. I definitely have cartoonists who are my favorites. I consider myself a good student but sometimes I am a slow learner with certain things. To the point that it embarrasses me. One of the latest things, one of the eureka type moments I've had, is a few years ago I was revisiting a few comics that really inspired me to move forward as a cartoonist. I'm thinking of stuff as varying as

Dark Knight Returns and

Love & Rockets the magazine issues. These are comics I read very early on. At the time when I read them as a kid, I wanted to grow up to make comics like those guys. I wanted to make my

Love & Rockets-type comic. I wanted to do something with the same spirit as

The Dark Knight Returns. Revisiting that work after so many years -- I would read them on and off again, but I had this eureka moment this time where I was thinking, "I will never in a million years be able to do this kind of comic." I guess as I've become friends with and talked with other cartoonists, I could see how parts of their psychology crept into their work. I realized that you have to put a certain amount of yourself into the work, right? That's when I had this realization, I think. Not just, "Oh, man, I'm never going to be able to make comics like this."

I have to look within myself and figure out who I am and see what I can bring to the table that no other cartoonist have an interest in or whatever. That's how

Wizzywig came about and that's how this hip-hop thing comes about. I don't think there's another cartoonist who can tell this story the way that I'm doing that. I believe that with some confidence. Don't get me wrong: there are other cartoonists who have hip hop flavor and are inspired, but the way that I'm doing this, I'm really trying -- as cliche as it sounds -- to make a comic I want to read. So I'm putting what I want in there. It's cool there are other people down with this and see where it's going. They're along for the ride it seems.

SPURGEON: Let me wrap this up with a fan that's partly a question for you as a fan. Is there a character in your book that surprised you -- maybe one you liked that you didn't think you'd like, or someone whose scenes you grew to particularly enjoy doing. Is there anyone in there like that?

SPURGEON: Let me wrap this up with a fan that's partly a question for you as a fan. Is there a character in your book that surprised you -- maybe one you liked that you didn't think you'd like, or someone whose scenes you grew to particularly enjoy doing. Is there anyone in there like that?

PISKOR: There's no one in particular, but there has been some interesting stuff that's come up through my own research an interests. I have tremendous respect for Kool Moe Dee. I've had it for years, but it developed over a lot of time. I remember for first grade, for music class, we had to dance -- we did some sort of dance thing to that song he did, "

Wild, Wild West." You remember that?

SPURGEON: Sure.

PISKOR: I recognized that as a piece of garbage in the first grade, so I always thought he was cheesy. But then when you discover his root and where he came from and how he listened to record executives to create that kind of style, where kids could listen to his lyrics and learn them -- he slowed his style down a lot. Then you realize he just kind of sold out, but he had a very, very strong foundation. But there's not like one character where I'm like, "Oh, this guy's the man."

SPURGEON: I wondered, because the work is so egalitarian. You have such an even-handed approach to your entire cast: no one's a bad guy, no one's a hero. I think that's an interesting way to portray a scene like that.

SPURGEON: I wondered, because the work is so egalitarian. You have such an even-handed approach to your entire cast: no one's a bad guy, no one's a hero. I think that's an interesting way to portray a scene like that.

PISKOR: Some people have criticized the way I do Russell Simmons. Early on, there are even flicks you can watch where he's got this funny eye, and he lisps a lot, and he was this flamboyant, wild character back in the day. They look at Russell Simmons as the way he portrays himself now: this meditative, Zen Buddhist yogi-type guy. A vegan. He absolutely did not start out that way. If I have my druthers with this story, you'll be able to see him develop over time as he becomes this sophisticated guy, a more worldly person and more considerate. But that's going to play out over time. That's not something you're going to fit into a first book.

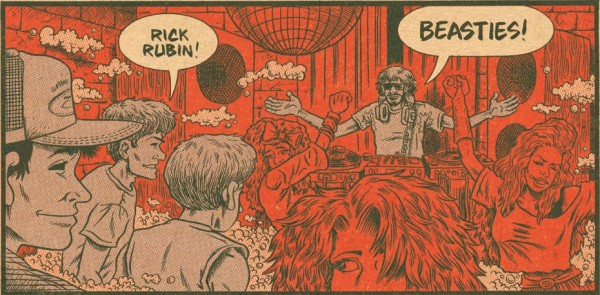

The Beastie Boys are the same way, man. They're pretty wild and crazy; their first album, they were going to call it, "Don't Be A Faggot." These are the same guys that spearheaded the Tibetan Freedom Concert, and became altruistic and philanthropic. These people start off very young, and we're all jerk-offs when we're young. Their stuff is just on record.

*****

*

Ed Piskor

*

Hip Hop Family Tree Vol. 1

*

Hip Hop Family Tree Vol. 2

*

Hip Hop Family Tree at Boing Boing

*****

* all images from

Hip Hop Family Tree except the photo which is about two years old and was taken by me

*****

*****

*****

posted 4:00 pm PST |

Permalink

Daily Blog Archives

November 2019

October 2019

September 2019

August 2019

July 2019

Full Archives