June 15, 2013

CR Sunday Interview: James Vance

CR Sunday Interview: James Vance

*****

The writer

James Vance is one of the forgotten forefathers of the modern graphic novel movement. He created

Kings In Disguise with the artist

Dan Burr at a moment in the comics industry's rapid development not yet a full decade removed from debates over whether longer, seriously-intended comics for adult were even possible. Unlike much of what was published at the time, that Kitchen Sink-published work's attention to Depression-era politics and its measured, serious narrative could appear on bookstore shelves today and feel right at home.

The sequel to

Kings In Disguise,

On The Ropes, hit store shelves this Spring a full quarter-century after the initial serialization of the first Vance/Burr work.

Ropes continues the story of

Kings protagonist Freddie Bloch, and extends some of that first book's major themes of displacement, isolation and the danger of making choices with limited information. Vance is also known within comics for a period scripting at the mid-'90s, you-had-to-be-there, idea-farm publisher

Tekno Comix and for his work helping to wrap up another 1980s classic,

Omaha The Cat Dancer, written by his late wife

Kate Worley. I am really pleased to get a chance to talk to James for a

CR interview. I enjoy his writing in comics and on-line. -- Tom Spurgeon

*****

TOM SPURGEON: James, I wanted to ask a few general questions before I leap into several on the new book. I guess my first one is I wondered if you could talk a bit about where comics fits into your spectrum of professional interests. How much time do you concern yourself with comics, as a writer and maybe even as a reader? How much do you consider yourself a member of that artistic community?

JAMES VANCE: Well, for the last few years most of my working time has been devoted to writing

On the Ropes and

Omaha, with any freelance journalism or editing jobs squeezed in around them. So comics have increasingly moved to the forefront of my professional life for most of the last decade.

Reading them has been something I've done on and off for most of my life. I moved on to other things throughout the '70s and early '80s, and started picking them up again when things like

Alan Moore's work and

American Flagg!, and later

Love and Rockets and

Omaha, caught my eye. I've never completely moved away from reading them ever since, taking a break for a year or two to take care of real life and then catching up on what I've missed -- I remember marathons of

Promethea and

Transmetropolitan after those series had been completed and collected... and, of course, checking out what my friends have done when possible.

Once I got heavily invested in writing

Ropes and

Omaha around 2006, my comics-reading time dwindled to practically nothing that I couldn't find online. For a while, I was buying new superhero stuff for my son and things like

Owly and

Amelia Rules! for my daughter, and I'd take a look at those. But when I got laid off during the big newspaper collapse a few years ago, finances made it impossible to keep that going. I still take the kids to the library so they can keep up on their comics, but I haven't had the time for reading a lot of the things I'd personally like to see. Now that I've finished those two big projects, I'm hoping to be able to check out some recent books that have intrigued me --

The Carter Family,

My Friend Dahmer and

Kevin Huizenga's stuff, for instance.

As to the artistic community, I guess you'd have to ask them. I feel like I'm doing the same kind of work they are, even if it's mostly been under the radar. If you'd asked me that 10 years ago, I would have said most members of the comics community probably didn't know I was still alive. But in the last few years I've caught up with people like Alan Moore,

Kim Thompson and

Gary Groth, and none of them seemed to be astonished that I was still breathing, and I've kept up with other people like

Neil Gaiman and

Howard Cruse all along, so maybe I'm not quite the cipher I thought I'd become. I'd like to be considered part of the community, but that's really up to them.

SPURGEON: Are there comics in Tulsa? Do they have a presence there? Are there any other comics-makers nearby?

VANCE: If you mean comics shops, sure, we're lousy with them. Some have been around for decades, and others spring up and then evaporate after a while.

As to a creative community -- at present, I just don't know. For the last few years, my life has been divided between dealing with my childrens' needs and pounding on a keyboard, with very little time for reaching out into the community. Back in the black-and-white boom days in the '80s, there were at least a dozen or so comics creators around here who were being published regularly, and I've been introduced to a few newcomers in the years since. And of course, some natives, like

Sterling Gates, do their most famous work after they've moved on to some other city. In a town this size, it's inevitable that there are a few at any time, and I'm confident that's the case now. Maybe we'll be hearing from them in the near future.

SPURGEON:

SPURGEON: Kings In Disguise

is a staggering 25 years in the rear-view mirror at this point. Re-reading it, that work struck me in some ways as both of its time -- for one thing, it's serialized -- and as one of those books that kind of presaged the current marketplace. Do you think that the context has changed for the way that book is received? Is it possible to read Kings In Disguise

the way you originally intended it to be read, with so many longer works having been done between now and then?

VANCE: This ought to be a short answer, but I'm afraid it won't be.

Kings was serialized because that's the way most comics were being done back then --

Don McGregor's early graphic novels were still largely anomalies, and things like

The Death of Captain Marvel were probably good ways to get readers accustomed to the longer format... but, right or wrong, those were really seen as little more than long-form superhero funnybooks with no more literary aspirations than a monthly

Marvel comic. Will Eisner had only published a couple of his graphic novels at that point, and I'm not sure I'd seen either of them when I was working on

Kings -- though I was certainly aware of his work at that time. So there wasn't much of a tradition to hook into at that point.

The truth is, I thought of it in terms of a collected work from day one, and that's the way we approached it. If you look at those individual comics, you'll see there's no concession to serialization in the story itself, no cliffhangers or any of the mechanics that you see in regular monthly comic books. Kitchen Sink created a pretty clever recap format for new readers, but that was the editor, Dave Schreiner's, addition to the individual issues, a publishing decision. It didn't affect the writing.

I imagine it still has that serialized feel because it's a picaresque, a style that almost has to be episodic since it requires constantly traveling to new locations and meeting new people. And, to me, it had to be that because it's about a 12-year-old kid who has no idea what the hell he's doing, trying to take a cross-country journey at a time when the world seems to be falling apart.

But really, the way I intended it to be read was just as a story. I'd never written comics before, not a single page, so I wasn't trying to do anything that was particularly game-changing. Sure, it was obviously a more serious attempt than, say, something with Wolverine in it. This was a time when people were doing a lot of talking about the infinite possibilities of the comics form, and I didn't see why I couldn't take a stab at exploring that.

In the early days of writing the story, I was probably more aware of moving into a new form than I needed to be. I was very conscious of the way

Harvey Kurtzman had used historical minutiae and logistics in some of his war stories for EC, and

[Will] Eisner's thoughts on the integrity of the individual page, and those general notions were in the back of my mind all through the writing. When I was writing the first installment, I remember asking Dave Schreiner about a character I'd called Joker in the original play. It was just one of those judgmental period nicknames like Gimpy or Squint, but now that he was going to be in a comic book, I wondered if maybe I should call him something else so the specter of Batman didn't intrude. Dave's response was something like, "Yeah, good idea. Let's call him Doctor Doom." And that's the point where I stopped worrying about where I stood in relation to anything else in the field. I just wrote the story in the way that made sense to me, and my only concession to the form was making sure there were things Dan Burr could draw that took advantage of his skills.

As to how it's perceived now versus then, I suppose knowing its background could affect how it strikes you. I've never really thought about it. Back when I was writing it, there wasn't any statement intended about my work versus anyone else's, and to my mind the only difference now is that if you want to read a graphic novel there are more choices than there used to be. I've spoken to people who read it recently without any awareness of comics history, and they didn't seem to find it particularly old-fashioned. I think it still holds up and that's all I can ask no matter how many other graphic novels have been done since then.

SPURGEON: Do you feel any sense of attachment to the idea that your work helped shape or inspire the current market? What do you think of the current landscape for longer-form work?

SPURGEON: Do you feel any sense of attachment to the idea that your work helped shape or inspire the current market? What do you think of the current landscape for longer-form work?

VANCE: When

Kings was reprinted in 2006, and recently when

On the Ropes was released, a lot of writers started referring to

Kings with words like "classic" and "ground-breaking" and I found myself thinking, Gee, I wish somebody had told me that at the time. For years, whenever that book came up in conversation, my standard little gag was "My footnote is secure" [Spurgeon laughs] and that's really the way I thought about it. I'd love to believe that we might have inspired somebody to do good work of their own, or shown some publisher that it's possible to take a chance on something that isn't just the same old basic genre tropes. If anyone can ever show me that was the case, I'd be thrilled.

The current landscape? In some ways, I think it's better than it's ever been. More people in general have at least some idea of what graphic novels are, and there's a real chance that a talented creator can publish something that will really speak to people both outside and within the regular comics readership. For that matter, most of the mainstream reviews of

Ropes have treated it more as a story than specifically a comics story. Subject matter has gotten more and more varied, and it seems to me that the creative people are taking more chances and occasionally speaking more from the heart. It feels at times that there's more effort being put into the art and the production values than the writing, but I have to believe that'll come, too. The more important your subject matter is to you, the harder you'll work to realize it in both the art and the writing.

In some ways, of course, large portions of the graphic novel shelves just look like jumped-up comics racks. For every book that's actually about something meaningful, there are a dozen that are just collecting issues of superhero comics or retreading a

Jason Statham movie plot. How many stories do we need about a hit man or a spy trying to get out of the business, but first he has to go on the lam and shoot a bunch of people? There's still a lot of lowest common denominator stuff out there. But given a world that pretty much gives

Gilbert and

Jaime [Hernandez]

carte blanche and allows

Eddie Campbell and

Seth and so many of those pesky younger people to do their thing, plus somebody like me when I bother to resurface, I can't complain.

SPURGEON: Forgive me for asking, but what's the first thing that comes to mind when someone mentions Tekno? Do you think that company has a specific legacy at all?

SPURGEON: Forgive me for asking, but what's the first thing that comes to mind when someone mentions Tekno? Do you think that company has a specific legacy at all?

VANCE: Yeah, I really need to do one more blog post about the Tekno experience one of these days, don't I?

Okay, the first word that comes to mind is "clusterfuck." [Spurgeon laughs]

The Tekno gig was a job that came along just when I really needed one. And it was a chance to do an ongoing series, which was something I'd never done. The money was good, I got to work with a talented artist --

Ted Slampyak -- and, except for a very simple premise provided by Neil Gaiman, I was able to invent the whole thing from the ground up.

But in the long run, yeah, it was a clusterfuck. It always seemed to me that the editorial staff's hands were tied, and they were just passing along some pretty stupid directives forced on them by clueless suits from on high. They'd bought some undeveloped vague notions from the estates of Gene Roddenberry and Isaac Asimov and then tried to turn them into superhero series. They were trying to create their own little Marvel universe without earning it, and the harder they tried to force it, the worse the books got. They used to send me copies of everything, and so much of that stuff was unreadable, I stopped bothering to open the envelopes.

Ted and I were interfered with just like everybody else, but I think we survived better than most because we developed real characters to work with instead of a bunch of empty tights, and because our book had a sense of humor -- our

Mr. Hero wasn't really a superhero series at all, though we sometimes parodied stuff that was going on in the superhero books of the day. So there's no need to forgive you for asking. I'm not embarrassed by the work Ted and I did for them, and I'd work on those characters with him again. I just wish that Tekno hadn't made it so difficult to do good work at all.

But a legacy? I'd say it was more of a warning. You can't buy reflected glory just by pasting big names on the cover. And you can't create anything good if you don't trust the professionals to do their jobs. From what I read in the comics press, there are companies out there who still haven't figured that out.

SPURGEON: Talk to me about the provenance of this book. Kings In Disguise

was famously a play first; was this one a comic first? What's the publishing history that got this work released?

VANCE: On the Ropes was a play, too, and it's actually several years older than Kings. In terms of Fred's story, the two plays were written in reverse order. I wrote the original one-act

Kings in Disguise as a way of finding out how this kid started out on the road in the first place.

I started thinking about adapting

Ropes to comics as a follow-up back in the '80s, but the time was never right to clear the decks and start on it. I knew it would take a hell of a lot of research to do it right, and life kept getting in the way. As the years went by, I'd take on little odd jobs for comics editors I knew -- mostly for Phil Amara at

Dark Horse -- but it just wasn't possible to carve out the block of time I knew I'd need, and the impetus just drifted farther and farther away. After a while, I started thinking of myself as somebody who used to write comics.

I remember a couple of occasions when I'd make some snarky remark about my wonderful career in comics, and Kate would grab a copy of

Kings off the shelf and shove it in my face and say, "You did

this!" She always believed in that book, and trust me, you didn't talk Kate out of the things she believed in. And of course, if I hadn't written it we never would have met.

It was a few months after she died that I got the offer from

WW Norton to reprint

Kings, and part of the deal was for us to do a sequel. While she was fighting her cancer, maybe even earlier, I would have turned it down, but now there was no way. As far as I was concerned,

On the Ropes was for Kate. So I signed the contract and gave it my best.

SPURGEON: I'm not sure that I've spoken to a lot of people that have worked directly with Norton as a publisher. How much support did you receive from them? Was there an editorial give-and-take? Is there anything they do with a comics work that other publishers might not be able to do, or are they are a pretty standard publishing outfit that way?

SPURGEON: I'm not sure that I've spoken to a lot of people that have worked directly with Norton as a publisher. How much support did you receive from them? Was there an editorial give-and-take? Is there anything they do with a comics work that other publishers might not be able to do, or are they are a pretty standard publishing outfit that way?

VANCE: Norton's a good house, one of the last really good independent mainstream publishers, and I think they treated me really well. Our editor,

Tom Mayer, was always available and always supportive, even when it became obvious that the book was going to take a lot longer than we'd anticipated. In the early days, Tom asked me to send script pages to him, but he never made suggestions about the writing or tried to steer us in any way, and after a while, he apparently trusted us enough to just wait for the final product to be handed in. They're the ones who brought out the Will Eisner library, so I felt secure that I was working with people who had good taste and a respect for the medium, not just a publisher who'd jumped on the graphic novel bandwagon.

When they were bringing out their first wave of original graphic novels, they asked me to go over those books from the point of view of somebody who knew comics, and I thought that was encouraging, that they'd take that extra step to be sure they were turning out the best graphic novels they could. And when

Ropes was finally in proof, I was impressed by how carefully their editorial and proofreading people worked on the book. They found a couple of little historical inaccuracies for me to fix before we went to press -- minor stuff, but I'd worked like hell to get that book right down to the molecular level, and the fact that they'd dug deeply enough to find anything impressed me.

I'd say one advantage they may have is access to the mainstream press. We've gotten some nice reviews on the comics blogs, but let's face it, the book's in black and white and there aren't any superheroes in it, so not everybody's going to cover it. But we've been reviewed in a surprising number of big city newspapers,

Paul Buhle just gave us

a fantastic write-up in In These Times, and I've done a couple of interviews on nationally syndicated radio shows. Norton can't get us good reviews, but I think by virtue of being Norton, they can at least get certain people to give us a look in the first place. So I have to believe that if nothing else, their reputation can help us get noticed by potential readers who might never have heard of us if we were with a traditional comics publisher.

SPURGEON: What works for you thematically about this book as a sequel? There are certainly elements of Kings

in here, and I was wondering how you think this works as a second story and how this might stand alone.

VANCE: There were a couple of things going on with this one. Way back in the mid-'80s, when I was just starting to write the

Kings comics version, I had the notion in the back of my mind that if I wasn't laughed out of town, we just might be able to continue on with

On the Ropes... and I was intrigued with the idea of writing two books that comment on each other, that don't let you read completely between the lines, have access to the complete subtext, unless you read both of them. And yet you could read either one without the other and have a complete story. It wasn't the kind of thing you want to get too precious with, so I only salted a few bits of this into

Kings, but they do exist, at critical junctures in Freddie's story. And to play fair, I tried to make it possible for people to pick up on those bits of subtext in

Kings alone if they paid close attention.

Maybe I was asking too much of the reader, or maybe I didn't plant the pointers strongly enough -- I was trying to be a little subtle about it, but who knows? When the reprint came out, there were a couple of reviewers who'd obviously put the most simplistic, clichéd spin on some of those points -- and then took me to task for them -- and I remember thinking, Thanks for the vote of confidence, guys. But, then, they'd only read the one book, and maybe I was asking too much for them to do that much work when a simple solution seemed to be staring them in the face.

So I was glad to have the chance to finally follow through with

Ropes. I think we made those connections without being too blatant about them, and now there's a legitimate chance for you to read the two books and make those discoveries for yourself.

On a less pointy-headed level, as the work went along I became aware of how much the whole thing is concerned with consequences. That's what every story should be about, of course, but every major character here is playing for high stakes in a volatile atmosphere, and some of the biggest obstacles they have to overcome are there because of their own past actions. And then they perform a new action and there's a whole new set of consequences added to the mix. These people are all juggling chainsaws, and in a way this whole series of incidents can be traced back to a bad snap decision that Fred made near the beginning of

Kings in Disguise. If he hadn't gone on the road years before, some of these other lives would never have been affected in just this way.

You ask if

On the Ropes stands alone, and I think it absolutely does. I think both of them do. But my hope is that reading both is a richer experience, the second one giving us a clearer sense of the mistakes Fred made in

Kings and just what that book's ending meant, and

Kings giving us a better sense of the innocence he's lost by the time we get to

Ropes.

SPURGEON: It's been a long time between books. Was there any effort necessary on your part to approximate a style or approach that might have put this book into continuity with the previous work? Was it a natural voice or approach to which you returned here? How conscious are you of style and tone when you work?

SPURGEON: It's been a long time between books. Was there any effort necessary on your part to approximate a style or approach that might have put this book into continuity with the previous work? Was it a natural voice or approach to which you returned here? How conscious are you of style and tone when you work?

VANCE: Recapturing Fred's voice in the narration really gnawed at me at first. I remember talking to Neil Gaiman about it early on, and he told me not to tie myself up in knots about it, that nobody would expect me to write exactly like I had all those years ago. And he was right, but I still wanted to have some stylistic continuity between the two books, so I worried at it for a while before I was really satisfied with it.

The worst part of it was that I'd started to work on

Omaha at almost exactly the same time I started

Ropes, so for the entire writing period I was not only trying to recapture the way I'd written a character in the 1980s, but I was also trying to echo Kate's stuff. It was a pretty schizophrenic experience at times, shifting from one to the other, sometimes on the same day.

Yeah, I'm pretty aware of style and tone. I tried to give the characters distinctive voices and ways of expressing themselves -- older characters like Gordon and Barbara use slang a little differently, and have different points of reference than Fred or Eileen, that kind of thing. And Fred has two different voices -- the one he uses in dialogue with the other characters, and the one we read in the captions. The narration is obviously by an older Fred looking back and trying to recreate the way he felt in younger days. In

Kings he's trying to recapture the unsophisticated dreams and general cluelessness of a 12-year-old boy, and in

Ropes he's recalling the viewpoint of a teenager who hasn't so much matured as become more cynical and withdrawn until that old capacity to dream is awakened and pointed in a new direction. And, of course, the narrator Fred is self-educated and a slightly awkward writer -- but I tried not to make him so awkward that his captions are a chore to read.

SPURGEON: The book hinges on a mechanism having to do with union organization and how different parts of the movement communicate to one another... did you base that on something you researched, or was that a creation of whole cloth?

SPURGEON: The book hinges on a mechanism having to do with union organization and how different parts of the movement communicate to one another... did you base that on something you researched, or was that a creation of whole cloth?

VANCE: I always thought that angle was the weakest part of the original play. I lost count of how many times I rewrote that part of the story, but it wasn't until I did the graphic novel version that I finally licked it. The actual mechanism was my invention, but what helped me work it out was reading oral histories by people who'd taken part in the steel strikes in Chicago. They were utterly paranoid about management getting spies into their meetings, and were constantly worried about loose lips giving everything away. And the worry about local police undermining them and trying to frame them for crimes was very real. But they still had to stay in touch with the outside world, and this sort of

Rube Goldberg system of mail drops was the way I came up with to deal with that and to get Fred involved.

SPURGEON: More generally, what interested you about the labor movement during that specific time period? Is there anything that surprised you, that you dove into after a broader survey revealed one or two things?

VANCE: It's been so long now that the memory's a little hazy, but I think it came from an initial curiosity about the Shakespeare plays directed by

Orson Welles in the 1930s. Remember, this was back when I was writing plays, so I was curious about theater history. Reading about Welles'

Macbeth and

Caesar for the WPA Theater led me off in different directions -- the conservative backlash against

the Federal Theater Project, the climate of unrest over labor strikes that led to the cancellation of

The Cradle Will Rock, and from there to learning more and more about the labor movement itself. I think the biggest surprise while I was following those threads was learning that the government had sponsored a circus. I was charmed by the whole idea. And I was riveted by the drama of the labor struggle in those days, the absolute viciousness of some of the company owners and the way that people were literally putting their lives on the line for better working conditions. The more you learn about that period of history, the more fascinating it is.

SPURGEON: One thing I find intriguing about what you do with

SPURGEON: One thing I find intriguing about what you do with On The Ropes

is that you play your protagonist against a series of deeply troubled adults... it's almost an expansion of the contrast between the two road companions in Kings

. That seems to me very stage-oriented... what appeals to you about the technique of putting sets of characters against one another like that, and why do that with more than one here?

VANCE: Part of that's by design and part of it's just inevitable. It's 1937, the economic recovery's stalled, and a lot of people are still hanging on by their fingertips. It's just a given that you're going to see some troubled adults here and there.

The simple answer is, it made sense to me. In the years between the two books, Fred's been wandering in the wilderness alone, and he's just gone further and further inside himself. So in this story he's re-emerging into the world and I wanted to see him having to step up and deal with a lot of people on different levels. He gets along with the roustabouts, but not on any intimate level, and of course there's Eileen, but... hello, hormones. She's his one attempt at anything like a normal relationship, and you can bet that he didn't make the first move. He's really too much of an outsider to be comfortable with people living normal lives.

And with Gordon we have another kind of outsider who looks like he's able to function in society but who's really more screwed up than Fred is. What makes their relationship work is that each of them believes, in a different way, that he doesn't need anybody... and a lot of the story is about the individual ways they learn how wrong they are, and how much it costs them to learn it. It's not all cut and dried, it's a messy process. There's nothing messier than the way people live their lives. Gordon works hard at being an asshole, but he has moments when his conscience gets the better of him, and of course he goes to some pains to keep Fred out of harm's way when he doesn't really have to. Fred's idealistic and often naive, but he's capable of throwing his political ideals under the bus -- not to mention absolutely betraying Gordon's trust -- when there's something in it for him.

If you look for it you'll find questions being raised about the individual versus the collective, the kind of thing that was getting a lot of lip service in those days... but the honest truth is that I wrote what I did because I really enjoy the byplay of interesting characters. As a reader and as a writer, I'm fascinated with eavesdropping on what they have to say to each other and watching how they try to coexist. To me, that's the heart of drama. Not just drama -- or comedy -- in terms of the stage, but any kind of storytelling. Contrasting people and ideas playing off each other, and the old "human heart in conflict with itself" thing.

SPURGEON: You frequently work in silent sequences, which I find a compelling choice given your natural tendency towards very strong, methodically text-driven scene work... is there a reason in general you go to such moments? Is there a specific kind of scene you think flattered by that approach, and are you simply just having contrasting approaches in order to break up the longer narrative?

VANCE: The short answer is, if you're working with Dan Burr, you'd be crazy not to take advantage of it. Whether it's theater or comics, silence is a powerful way to focus our attention, and Dan's talent is a precision instrument. I don't think he gets enough credit. A lot of this stuff just wouldn't work like it should without him.

Sometimes it's just a matter of rhythm, a moment of silence to counterpoint a particular narrative passage like a rest in a piece of music. Sometimes it's because we're involved in a particular type of action where, realistically, nobody would be talking. There are a handful of violent moments that are dead silent because my model for those were real life, not Marvel Comics. And sometimes it's time to just shut up and let Dan tell the story. With Dan, I have a collaborator who can draw people thinking and feeling in a way that evokes real life, in all the different shades of grey that we experience. There's a two-page sequence I wrote that's completely wordless, but it's one of my favorite moments in the book. Fred's at the lowest point of his life, and Dan takes us through all the changes he goes through at that moment. There's no need for dialogue, no need for the narrator to say "I was heartbroken" -- we can see that's he heartbroken, and by showing us, Dan breaks our hearts a little, too.

SPURGEON: Can you talk about the woman writer character, where she came from? I liked that a lot of her scenes came late in the story, and the saga kind of pivots on her, which you usually don't see? How much work do you do on characters before kind of bringing them into a story... how thoroughly do you know them before you use them?

SPURGEON: Can you talk about the woman writer character, where she came from? I liked that a lot of her scenes came late in the story, and the saga kind of pivots on her, which you usually don't see? How much work do you do on characters before kind of bringing them into a story... how thoroughly do you know them before you use them?

VANCE: In this case, I guess there's a certain luxury in having done an earlier version of your characters. In the case of Barbara, I can't say I'd been worrying about her since 1979, but I'd always been vaguely dissatisfied with her in the original play -- I kept rewriting some of her scenes, and I was just lucky I had a good actress to pull that together for me in performance. So when it was time to revisit her for the graphic novel, I knew what some of the problems had been with her character before, and I was able to look at her with fresh eyes.

The play was kind of a rough outline for me that I kept at the back of my mind. I don't think I actually looked at it more than two or three times while I was doing this version, and I didn't crib much of the original dialogue at all. It helped, of course, to know where the characters were going in a general way, but within those rough guidelines there was still a lot of discovery during the actual writing. That's true for all of the characters, but Barbara's probably the one I learned the most about during the process.

She represents what Fred thinks he'd like to be, and that gives her the power to tell him when he has his head up his ass. And despite her hard shell, she can see a little something of her younger self in him, so she's willing to reach out beyond their business deal and try to show him where he may have pointlessly screwed up his life early on in

Kings in Disguise. She's tough, but it's a kind of self-conscious toughness born from defensiveness and loneliness. There's a little bit of that brittle literary cocktail party air to some of her dialogue -- nobody else in the book would use a phrase like "when the juniper berries were in bloom," even though she's pretending to be ironic -- but at the same time she's a little embarrassed by her own wistfulness for a lost world.

I haven't had much feedback on her, but I suspect she's the most difficult character for some readers. She talks about ideas. The world's let her down, so she's convinced there's no hope for change. She made a writer I know very uncomfortable because she represents failed aspirations. She's the character who tells us to get over ourselves, and who wants to hear that? But just for a moment, she's allowed to understand what fuels Fred, and that lets her dare to hope again that she can make her mark. She's difficult, but I'm very fond of her, and I'm proud of the scenes I was able to give her.

SPURGEON: Is there a context for this book in terms of labor history, or fiction about labor that's not comics? How has the book been received -- or has it been -- by audiences that might be amenable to its politics?

VANCE: The best piece of fiction I've read on the subject is

In Dubious Battle, which gets referred to in

On the Ropes -- but I'm not going to put myself in the same class. I think you can read it as being in that tradition, but I'm more interested in the characters than their cause. It's just that some of them are utterly consumed by the labor struggle, and for good reason, so it may be hard to separate their personal stories from the huge events that are sweeping over them. Their stories take place during a vivid moment in time, and we went to a lot of trouble to make that setting as authentic as we could. I worked hard to keep the timeline straight, and I tried to make the characters' attitudes accurate for the times. I don't want to read a story with 21st century ideology transplanted onto a period setting just to make the reader more comfortable. I'm not going to play coy and say you can't call it labor fiction, but to me it's also fiction about characters who are working out their personal struggles against a background so infused with the labor struggle that they can't avoid it.

I'm not big on Googling myself, so I may have missed some of the coverage. I mentioned that

In These Times gave us a review, and there was one from a homeless paper in Washington. I can't really say what else is out there. All the reviews I've seen have been positive, which is amazing, and none of them have called us out on our politics or particularly praised us for them. The overall response has been to judge us on artistic terms instead of centering on the labor material, so go figure.

SPURGEON: The climactic final scene is messy and awful and really, really violent. How assiduously do you choreograph that scene, and how much of that is left to Dan?

SPURGEON: The climactic final scene is messy and awful and really, really violent. How assiduously do you choreograph that scene, and how much of that is left to Dan?

VANCE: Knowing that I'd eventually have to write that scene haunted me from the moment I started writing the book. I'd go to sleep trying to work out all the pieces, and the next night I'd do it all over again. The original production of the play really nailed it -- the sheer brutality was just breathtaking -- but another production I saw a few years later completely ruined it, almost turned it into a shaggy dog moment. So I was hyper-aware of how easily you could screw it up.

Part of what made it gel in my mind was the realization that Fred would have to get actively involved in that action in a way that he hadn't in the play. That was when it started to make sense to me. I saw that we needed Fred to participate for logistical reasons, and that made the scripting come together. And now Fred would have to own some of this, and that was the final piece of his character arc that I'd been missing.

Dan and I corresponded about it for months. I had to plan it so it looked like spontaneous chaos, but all the pieces had to happen just right or it would fall apart. I think I was so obsessed with getting it right that I probably confused the hell out of Dan at one point with all my tinkering. For a while he was thinking about

Krigstein-izing it into even smaller micro-moments, and we just worked ourselves into a lather over getting it right. In the end, of course, he did it simply and brilliantly. I think it's a model of collaboration. It's just what I wrote, but only Dan could have taken that script and made it so beautifully awkward and ugly and effective.

SPURGEON: I thought one of the more compelling through-lines in terms of theme was the power that memory has over us... is that something with which you personally struggle? I know that I think more in those terms the longer I live. Do you feel like you're haunted by specific memories, specific feelings of guilt?

SPURGEON: I thought one of the more compelling through-lines in terms of theme was the power that memory has over us... is that something with which you personally struggle? I know that I think more in those terms the longer I live. Do you feel like you're haunted by specific memories, specific feelings of guilt?

VANCE: I don't know that I struggle with it more than anyone else... or maybe I'm so consumed with regrets that I can't tell the difference. Like anyone who's lost someone they loved, I can find myself wishing I'd done something better or differently for them while I could. I was expecting people to pick up on Gordon's pain and assume I was working out issues from Kate's death, but the truth is, that angle was in the original play that I wrote before I'd ever met her. Maybe I was able to bring more depth to it now, but if so it was subconsciously.

The book's told by Fred in the past tense, so of course, it's all a memory. And in this story, he's surrounded by people who have lost something so vital that they can't let go of the past. But I think the moments where they shine are the ones where they force themselves to move on -- not abandon their guilt and their memories because you can't do that, but to find a way to engage with life again in spite of it. That's why Gordon's a kind of hero at the end. He's manipulated everyone around him out of weakness and self-centeredness, but he finally changes his plans when he sees that the cost of wallowing in his own guilt is going to cost someone else too much. That guilt he refuses to accept.

SPURGEON: Are we going to get more comics from you? Where exactly does the Omaha

work stand?

VANCE: Omaha's finished.

Reed Waller turned in the final corrected pages a few weeks ago, and the book will be published around the end of summer. I can't tell you what a relief that is. Kate had asked me to finish it if she couldn't, and I hope I never put that much emotional pressure on myself with another project. I hope it would have been up to her standards, but I know it was the absolute best job I could do as her stand-in. Reed seems pleased with it, so now the question of how we did will be up to all those people who have been waiting for a conclusion all these years.

What I can tell you about doing more comics is this: At some point while I was writing

On the Ropes, I rediscovered how much I like working in comics. There's really nothing like the sense of discovery I get from the pressures of working in this form. With the right collaborator, a sensitive artist who's in tune with you, you can be as subtle and as serious about the material as you like, because after all that hard work it's going to be an absolute joy when you see the final product.

So more comics are a definite possibility. I've already been asked if I might have more to say about Fred Bloch, and the answer is yes, I know what happens to him next. And Dan's told me that he's up for another one if it doesn't take another 25 years. Recently, I've had ideas for some other kinds of stories that could work as graphic novels, too. So it's possible that you haven't seen the end of me yet.

*****

*

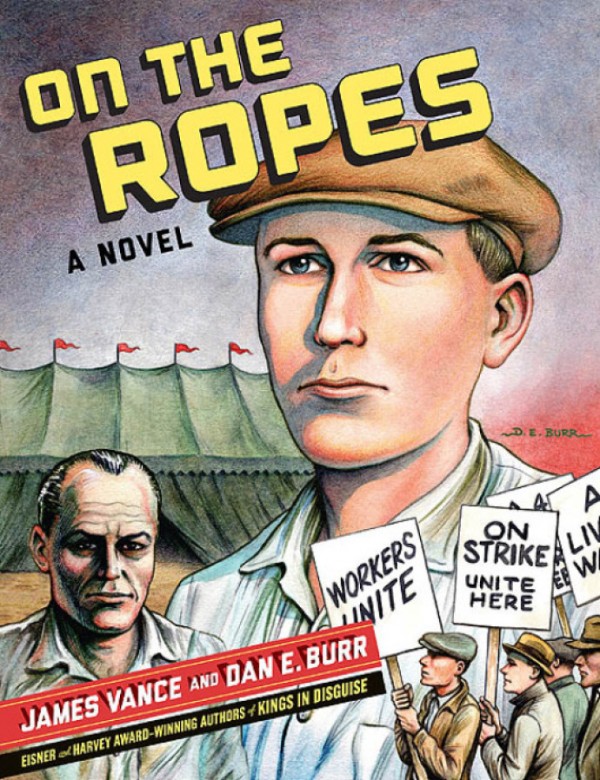

On The Ropes, James Vance And Dan Burr, WW Norton, hardcover, 9780393062205, 256 pages, March 2013, $24.95.

*****

* cover to the new work

* some of Vance's seminal comics-reading experiences

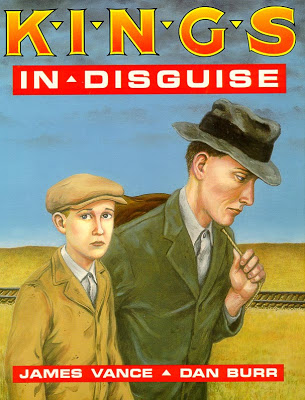

* a cover and a title page to

Kings In Disguise

* work for Tekno Comix

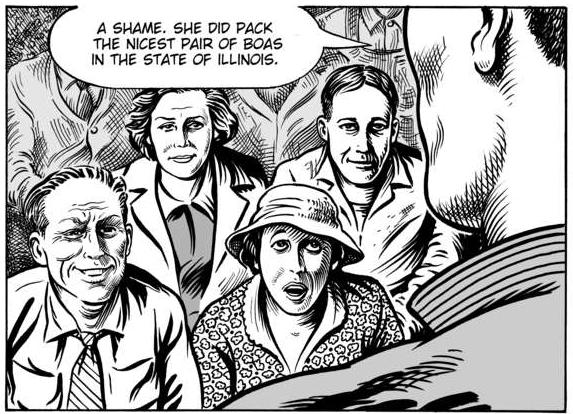

* various images taken from

On The Ropes, hopefully explained in context (include image below)

*****

*****

*****

posted 10:00 pm PST |

Permalink

Daily Blog Archives

November 2019

October 2019

September 2019

August 2019

July 2019

Full Archives