Home > CR Interviews

Home > CR Interviews CR Sunday Interview: Ben Schwartz

posted June 19, 2010

CR Sunday Interview: Ben Schwartz

posted June 19, 2010

*****

Ben Schwartz is a smart man and a good writer. It's a great thing that the industry has changed enough over the last two decades so as to be able to encourage working writers like him to participate through book projects like his forthcoming

The Best American Comics Criticism, a compendium of written pieces about comics chosen for their excellence by the book's editor. It's the kind of volume that starts fights -- let me assure you that my critical questions below about what gets covered and who is included are not Devil's advocate points; I'm the fool with myself for a client, and those are my real criticisms -- but that's okay and it's part of the fun. There's a lot of good work in the book and one or two absolutely inspired choices. Anyone with an interest in comics should at least give it a flip-through, and anyone with an interest in writing about the medium should use it as a springboard to discover a host of excellent new favorites. Ben and I conducted the following interview survey-style via the medium of electronic mail. -- Tom Spurgeon

*****

TOM SPURGEON: Was your own reading of comics influenced at all by writing on comics? When did you first become aware of writing on comics and what were some memorable early pieces of criticism you remember engaging? Were you an RC Harvey fan, a reader of Gary Groth's interviews, a "Funnybook Roulette" kid?

TOM SPURGEON: Was your own reading of comics influenced at all by writing on comics? When did you first become aware of writing on comics and what were some memorable early pieces of criticism you remember engaging? Were you an RC Harvey fan, a reader of Gary Groth's interviews, a "Funnybook Roulette" kid?

BEN SCHWARTZ: Well, not counting "

Stan's Soapbox," the first writing about comics I saw would be

TCJ or

the Legion of Super-Heroes issue of The Amazing World Of DC Comics. The idea that you could write a whole magazine on the history of a series one killed me. And that it had information on people like

Curt Swan or

Otto Binder. I read it to pieces, literally, 'til the cover came off. I first read

TCJ when I was 13 or so (1979) and met Gary at a Chicago Comic Book Convention -- which is how I first saw a copy, at the

Fanta table. I can't say it influenced me much at the time because no matter what Gary wrote I still kept buying superhero books. The first comics-related journalism I ever wrote was an outraged

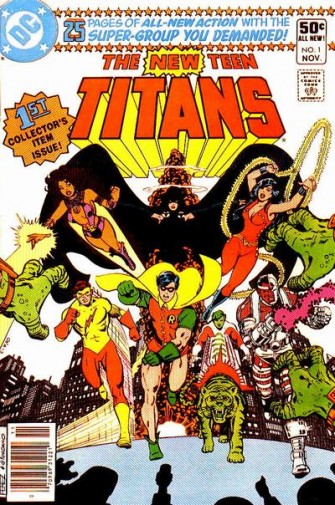

Teen Titans v

X-Men takedown in the 'zine of a comics club I joined, the Southeastern Wisconsin Comics Club (SWCC!). In

Ka-Pow!, I point-by-point dissected the

Titans as an

X-Men rip-off. Has the franchise recovered? I don't know. I was so into nerdville that when I first saw work by

Crumb and

Jaime Hernandez I thought, "Wow, those guys are good enough to draw for

Marvel."

What I liked most about

TCJ was

Gary's interviews. I barely had an idea that actual people wrote and drew comics beyond the names on the books -- I mean, any more than I knew there was a real Walt Disney at one point in time -- much less feature-length conversations with them. I grew up in Kenosha, Wisconsin and had no contact with "fandom" until I joined the SWCC. Fiore is the critic I remember from that time -- I always loved the Faulkner quote over "Funnybook Roulette," which is probably the first time I read

Wm Faulkner's name. Fiore's writing was fresh then and now. Fiore reviewed stuff I read along with stuff I didn't, so I no doubt picked up on stuff from him.

Carter Scholz, Bob Harvey, and later

Heidi MacDonald, too. I recall Gary so adamant about Marvel and

DC that reading him was like getting ready for a fistfight. I couldn't understand why anyone disliked superheroes that much. He won, tho. I wasn't an adult looking for comics to read then, nor a publisher trying to open comics up to something new. I mean, forget putting

Love & Rockets out,

TCJ may go down as the most groundbreaking publication Fanta ever did. The world has seen a

George Herriman, a

Schulz, a

Crumb. But a magazine devoted to comics commentary in the 1970s? An echo of that in writing about the 2000-2008 period came in realizing that with mainstream distribution of comics in bookstores, the need to bang your head against the brick wall (a metaphor Gary used, as I recall) isn't needed anymore. Gary and

Kim won a major victory in comics going mainstream. They used to rail against Marvel and DC because they dominated the sales, distribution, and creative life of comics. Now, not so much -- comics are reaching a bigger audience that knows superheroes comics as merch from movies like t-shirts and action figures. They meet

Ware and

Clowes in

The New Yorker, not a direct sales shop.

As for memorable pieces -- Gary's

Will Eisner takedown in 1988. Easily, because he touched on this third rail of comics -- attacking Will Eisner. Then, you had big names like

cat yronwode,

Denis Kitchen, and

Jules Feiffer in support of him, and a legion of fans who never questioned Eisner as comics' last word. He verbalized, albeit in his pitbull way, a lot of what I felt about Eisner but assumed, because of his universal acclaim, that I must be retarded for thinking. The firestorm Gary got didn't surprise me, but it was a great moments in comics criticism -- like

Andrew Sarris throwing down the auteur theory or the big personalized literary debates of the

Vidal-Mailer days. Gary challenged the canon while creating one in

Los Bros and so much else he published. He really drew a line that still causes argument.

David Halberstam once said something along the lines of, "any reporter with more than two people at his funeral is a disgrace to the profession." Well, that's Gary's attitude, and it's been pretty decisive.

SPURGEON: I know this is a pretty standard question, but how did this book come into being in a practical sense? What made you decide there might be enough work of this type to make a pretty good book? Was there a specific piece that convinced you to give a lot of this work a second look? Is it in the book?

SCHWARTZ: Doug Wolk edited

Da Capo's annual

Best Music Writing series some years ago and I thought, why not do that with comics? I'm writing another book for Fanta and pitched it to them and they liked the idea. Gary was the most skeptical. Early on he asked me if I seriously thought I could fill a whole book with good writing on comics. He sent me his essay "The Death of Criticism." Nice to know that's on your publisher's mind!

SPURGEON: To follow up, once you decided that this book could be done, can you talk about the additional reading you did, where you looked for potential pieces to include and the process you underwent in setting the final roster?

SCHWARTZ:

SCHWARTZ: I covered the waterfront. As I mentioned in my

BPRD interview with you, the biggest challenge was coming up with a roster that was unique to the book. That is, convincing a reader they had to own this book instead of looking at it on Amazon and thinking, "Why buy this when I can just Google it?" I e-mailed friends for thoughts on non-traditional sources for writing -- 'zines, panel discussions, on-line list threads, anything where the ideas were of value. That brought me to

Pete Bagge's

Ditko essay, Darell Epp's on-line interview with Chester Brown,

the videotaped panel with Daniel Clowes and Jonathan Lethem, and

the Pacho Clokey mini-comic I bought at

Meltdown years ago. The Moore interview was up on Youtube for months and then they took it down. It's the only case of Internet copyright infringement waste-of-time bullying of which I heartily approve -- because now the BACC has it! I went to some obvious places --

The New York Times,

Bookforum -- and the

Updike piece was a barely on the radar intro he did for a

Thurber reprint.

SPURGEON: Taking it from another direction: you wrote a very personal introduction to this book that I think a lot of people reading the book will enjoy -- I'm not sure that most introductions don't get skipped. Can you talk a bit about the development book as a way for you to satisfy a certain amount of intellectual curiosity? What did you learn in the course of doing this book? What surprised you?

SCHWARTZ: I learned there are a lot more question marks to this period in comics than I realized. The intro starts with a conversation I overheard about comics on the escalator at a Barnes and Noble here in LA between two teenage girls. My 14-yr-old self would not believe the 2010 me telling him that in the future teenage girls read comics passionately. Actually, these girls had better taste than I did back then. But, seeing the interest in comics from literary icons like

Lethem and

Moody and

Franzen and Updike in this period ... and then to see Amazon readers and mallrats argue as passionately as the literati, that range of fans was new to me. Debating fans on

TCJ's board, at cons -- yes. Those two groups -- new to me. Where else is that happening in publishing today?

Kitty Kelley v Oprah?

Also, there's so many new readers to comics and new talents coming in, the canon of who matters at this moment and what matters in comics at this moment is, as they say, a fluid situation. In the last ten years,

Dan Nadel and Doug Wolk have written books specifically challenging the baby boomer canon and back to the

Blackbeard and Marshall Smithsonian book. No one's done that in a long time. The revival of

Frank King,

Paul Karasik's Fletcher Hanks book -- it's all changing quickly. So, very serious people are asking us to wildly rethink the whole thing, and I had to rethink more than I thought I would going into it.

SPURGEON: If you haven't already talked about this, what made you decide to include a full array of critical inquiries -- interviews, introduction, historical pieces -- as opposed to focusing on direct appraisals of work? Do you think there's anything to say about comics that there is this strong variety in types of critical inquiry?

SCHWARTZ: I didn't want the reader to get bored, basically. Most "Best" anthologies offer a uniform set of essays/stories with various points of view. I wanted a lot of formats and points of view on the general topic of lit comics. A model I emulate is

Strong Opinions, a collection of hilarious introductions, interviews, essays, letters to editors, and arch rebuttals to other writers by

Nabakov. I love that book. My favorite collections of criticism mostly come from the music and film world, like

The Nick Tosches Reader,

Greil Marcus' Ranters, Ravers, and Crowd Pleasers,

Lester Bangs' sketchy collections, or

Manny Farber's collections. They're more accessible, less podding. They have that same mix of reviews, interviews, essays, etc. I just read (for research on a story)

The Bruce Springsteen Reader. That book is a pretty dazzling example of what I hope the

BACC will be -- and I'm not even that into Springsteen.

As to the last part of your question, it says two things. One, that a lot of smart people are thinking about comics in a lot of different ways and places. 2) There are very few regular forums, so I had to draw from a number of sources. Except for

TCJ,

Comic Art,

Comics Comics , no publication could do a comics anthology the way the

New Yorker can put out anthologies of its profiles, sports, or humor writing -- or

Rolling Stone can do musical genres. Given a few more years like we've just had, the

NY Times Bookforum could do it with comics criticism.

SPURGEON: One of the odder things about the book to me is that it's based in part in the flowering of literary comics but the "Appraisals" section is dominated by older works. First, why do you think that happened and was that intentional or a function of just what excellent writing was available to you? Second, do you think the rise of literary comics and the reclamation of the past through reprints and writing about those works are intertwined, and if so, what effect has that had on that kind of literary comic?

SPURGEON: One of the odder things about the book to me is that it's based in part in the flowering of literary comics but the "Appraisals" section is dominated by older works. First, why do you think that happened and was that intentional or a function of just what excellent writing was available to you? Second, do you think the rise of literary comics and the reclamation of the past through reprints and writing about those works are intertwined, and if so, what effect has that had on that kind of literary comic?

SCHWARTZ: Well, as to the older works, it's just easier to write a career, large-scale appraisal of an artist when you have decades of work. So there's that. I mean, George Herriman lends himself to overviews more than

Kevin Huizenga right now. Also, this book is about lit comics, but not about giving the reader a list of what comics to read. BACC means to reflect great critical thinking, so, it meant more for me to have Bob Fiore in it than a great piece about any single cartoonist. The It's why we have pieces by

Seth and

Chris Ware but nothing on them -- both are great thinkers about comics as well as compelling artists.

You say "older works," but In "Appraisals" I wanted great essays that gave a snapshot of the changing canon, where King and Schulz and

Gray have a determining influence on this lit era (Thurber, too, actually) more than they have in decades. So, yes, it's very intertwined, a point I wanted to make. The reclamation of a revised comics past rather than one dominated by

Kirby,

EC, Eisner, and

the ZAP underground is what much of the "Appraisals" section is about. Gray set down the first truly dramatic narratives in comics. Sure

Chester Brown admires his artwork, but Gray's pivotal impact -- no matter what one thinks of his politics or the schmaltzy musical

Annie -- has as much to do with comics writing today as it ever has -- including

Little Orphan Annie at its peak.

Jeet Heer's "Drawn from Life" is a landmark piece on King, as important to King as Gilbert Seldes' 1922 piece on Herriman, "The Krazy Kat That Walks Like a Man." Jeet pointed out to me once that every generation reinvents its canon, a comment often in my mind when I thought about the Appraisals section. So, as you say, "older works," but I'd say, never more vital.

Sarah Boxer's Herriman piece is the first great study I've read of Herriman dealing with the news that Herriman was Creole, not Caucasian. As to the youngstas of the bunch, Clowes,

Lynda Barry,

Phoebe Gloeckner -- the pieces about them speak for themselves.

SPURGEON: You touch on Europe's concurrent literary comics movement through a few piece, but the pieces that engage manga are limited to I think a single interview with Yoshihiro Tatsumi and I didn't see anything that dealt with an on-line comic. Do you think that's a weakness of the book? Was that about the kind of work or about the writing you encountered? How would you describe their omission to someone who really values those kinds of work and thinks they're as much a part of the modern comics movement as anything? Is there something qualitatively different about the writing done on those works?

SPURGEON: You touch on Europe's concurrent literary comics movement through a few piece, but the pieces that engage manga are limited to I think a single interview with Yoshihiro Tatsumi and I didn't see anything that dealt with an on-line comic. Do you think that's a weakness of the book? Was that about the kind of work or about the writing you encountered? How would you describe their omission to someone who really values those kinds of work and thinks they're as much a part of the modern comics movement as anything? Is there something qualitatively different about the writing done on those works?

SCHWARTZ: It's not an omission. It's just not the book they want to read. Tatsumi is not there to represent manga, but

gekiga, the Japanese version of lit comics. His choice to break with manga is as big as Eisner's in splitting with the superheroes, so that's why he's in it. I'm going by his definition there. As for on-line comics, I never came across a piece or interview about them that stood out like that. Do you feel, between 2000-2008, that a great piece of writing was done on on-line lit comics that I missed? Lit comics and it's post 2000 arrival in the mainstream lit world is what the book covers. I just didn't find anything on them that relates to the book -- or 2000-2008 Marvel, DC,

Dark Horse, etc. So, it's not a weakness of the book. It's the point of the book. I'm a huge

BPRD fan, but that's not in here. Except for

Pete Bagge on Ditko's Spider-Man and

John Hodgman on Kirby or

Gerard Jones on

Siegel and Shuster and the first wave of fans -- not much.

As for world comics,

David B,

Marjane Satrapi, those pieces appear because of their authors, Rick Moody and

David Hajdu, wrote great pieces on them. They did a great job of relating them to modern lit comics. In the intro I point out that we cover a long list of writers -- a really good one in my opinion -- but because I emphasize critics more than artists, the book leaves out many worthy artists: Joe Sacco, for example. You can't make a list of essential comics in 2000-2008 and not include him. But, I can, if I can't find a great piece on. Hopefully, the Satrapi piece makes the point of great non-fiction lit comics, that it matters.

Ivan Brunetti has done two great anthologies, and Houghton does one every year. So, if you're looking for comprehensive consumer guide, get those. I'd rather have a killer essay about something trivial than a trivial piece on a household name.

Also, the different sections have different demands: the History section is there to set up the lit era and how I see it through writers

Brian Doherty,

Paul Gravett, and Bob Fiore. It's functional to the book in that way. The Fans section focuses on the golden age of history and biography we're in for comics, and the focus both David Hajdu and Gerard Jones gave to the impact of fans on comics. The Reviews section, that's interesting because it sets aside the original topical and consumer guide purpose of reviewing and just shows off the writers. John Hodgman's piece on epic comics came out as a review of then current books. Now I hope people read it to read Hodgman and what he's saying about Kirby's contribution to lit-minded narrative up through today.

SPURGEON: Correct me if I'm wrong, but as creative as you are in finding different forms for critical inquiry, were all of these piece published in print except maybe the last one? Did you not find work worthy of inclusion from mostly on-line writers like Joe McCulloch or Abhay Khosla? Is there any worry that in leaving work like that out, you're not providing a full snapshot of what critical inquiry exists out there?

SCHWARTZ:

SCHWARTZ: Darrell Epp's epic interview with Chester Brown is represented (well half of it!) here as are the Amazon readers who went off on

Joe Matt's Spent. I missed Khosla! I also came across

Laurel Maury too late, and she's great. As for McCulloch, I mention him in the intro -- there's critics like him,

Tim Hodler, who I first encountered on-line. It's a matter of fitting the critic to my editorial slant. You know, a bigger problem for me was realizing I have more women cartoonists discussed in the book than women critics. Sarah Boxer's Herriman piece is it. But, most women on-line or anywhere I encountered were into superheroes and stuff that didn't apply here.

Linda Davis' Addams book had sections I liked, but it didn't apply in the way Thurber does today.

However, you asked about on-line critics. Here's what I think about on-line critics: by and large, they aren't as interesting as many print critics. I see a greater knowledge of comics in the on-line writers than MSM writing on comics. MSM critics often stumble to find something to say about comics specifics and have no history of it. But, MSM writers often have more insight. They may not know their Kirby inkers, but they generally read more literature and approach comics with a bigger frame of cultural reference. Often the better writers and bloggers are moving into print (and most print writers have no choice but to blog or review on-line in 2010). Print is a tougher area to break into -- the editors want more out of you. The

Comics Comics guys show up in

Bookforum.

You know what print venue has surprisingly weak on the subject of cartooning and comics? Of all places?

The New Yorker. Given their history from

Arno and Thurber to

Chast and

Booth and

Bruce Eric Kaplan and all the talent that

Bob Mankoff and

Francoise Mouly bring them, they sure don't publish with much passion about comics.

Anthony Lane fascinates me, because he was so tough on

Alan Moore in his

Watchmen review and then

Jane Goldman's script of

Kick-Ass. He takes the subculture vulgarity of comics to task -- unlike anyone since Gary, I guess. And I agree with him on

Watchmen, btw (haven't seen

Kick-Ass). That's what I'm talking about with that bigger frame of reference. All that dark gritty superhero sadism

Watchmen inspired -- he was appalled by it. Updike loved comics,

Gopnik wrote about Thurber and

Kurtzman, and

Spiegelman's Jack Cole piece is maybe the best thing they ever published on comics. They like to run on about their glory days, but that's the extent of it. They hire the best cartoonists, though. You know your side is winning the culture war when Ivan Brunetti draws

New Yorker covers.

SPURGEON: You include two of the older statesmen in terms of writing about comics, Donald Phelps and RC Harvey. Both made their comics-writing reputation by writing extensively about newspaper strips, and yet you have them both writing about modern comics. Was that intentional? From an editor's standpoint, what do you think each writer brought to the works in the pieces you include?

SCHWARTZ: No, not intentional. I was looking at a

Caniff section from Harvey's

Meanwhile but he sent me the

Bechdel piece, which is good as a review/analysis but also as a mini-manifesto of how he thinks comics should be reviewed.

As for Phelps, yeah, I did like the generation/gender contrast of him covering Gloeckner and Barry. It wasn't intentional, though, in the sense that I was looking for that anymore than I was with Harvey and Bechdel. I really liked the Barry piece and then he connected it to Gloeckner and so I added that because it said as much about him as them. That someone who has been thinking about comics as long as he has takes such delight in those artists is what I was interested in, mostly. Nothing worse than a humbug pining away for the good old days. I'm just thinking about it now, but it's funny that the Appraisals section worked out that younger writers are covering Eisner, Gray, and King while Bechdel, Clowes, Gloeckner, and Barry get the "kids." By kids I mean artists hitting 50, with Gloeckner the tot of the bunch. By younger writers, I mean 40-yr-olds …

But, with Phelps, I guess it goes back to me on the escalator, eaves-dropping on the iCarlyites -- a motif I had not considered until this moment. It ties into the changing audience and creators of comics.

SPURGEON: Can I ask after cover choice of Drew Friedman? How did that come into being? Was the concept yours or Drew's? Do you think it's odd in any way you're bringing to some public recognition these writers about comics but then also kind of mocking them on this cover?

SCHWARTZ: I told Drew I wanted to do a send-up of Charles Burns'

Believer magazine and anthology covers, something Burns has made as iconic as Eustace Tilley on

The New Yorker. All I asked Drew to think about when he did the faces was to come up with a gallery like his

Comic Book Store Clerks of America They'll Never Own A Yacht. He came back with those amazing faces, and then Fanta's Alexa Koening did all the precision design work that makes the parody so funny. I added the captions. None of the writers in the book appear on the cover -- Drew promises!

As for mocking the idea of comics critics ... oh, guilty! I love the way cartoonists portray critics. Clowes' Harry Naybors (whose bookshelf includes "The Buscemas of Brooklyn"), Seth's Art Stern (whom we include in the

Wimbledon Green on the day a critic is born), and then

C. Spinoza's Pacho Clokey a hilarious mini-comic I included in full that parodies overreaching critics by one "Nate Guinzburg." I love the fake comic the author (who prefers to remain anonymous) created and the equally fake critic to annotate it for us. It's like an eight-page

Pale Fire. And with the caliber of writers in this book, I didn't think I had a lot to prove to the public as far as whether criticism of comics needs to be taken seriously. Maybe it goes back to my instant "Oh, yeah?" reaction to Gary when I was 13! Besides, comics critics can take a joke. We'll always have sports writers to make us look normal.

SPURGEON: I love the inclusion of the Amazon.com comments section on Joe Matt's

SPURGEON: I love the inclusion of the Amazon.com comments section on Joe Matt's Spent

. Were there any hoops to jump through to run that material? What about the quality of that stuff made you decide to include it?

SCHWARTZ: Hoops? Not much. What made me want to include them was Rick Moody's thought, or as they say in the East, "notion," in his David B. piece. He said that cartoonists were the subject of debate as fierce as any on

Vonnegut or

Richard Brautigan. Of all the cartoonists he names only Joe still inspires fistfight-level debates. Joe gets the most wide-ranging reaction of anyone I've seen, from genius to hopeless. You can write that, as I just did, but you can't truly believe all that about an artist. Also, I come from a DIY-inspired writing background -- blogs,

Suck.com, 'zines -- that says one's point of view matters more than the corporate imprimatur on the masthead. I could have done an Amazon thing like that on any cartoonist out there, but Joe is Joe -- only Joe Matt drives people to such distraction.

SPURGEON: You've written about comics and cartoonists before. In fact, you call on your number with the inclusion of a piece. With whom in the book do you find the greatest critical sympathy? Was there anyone that was an eye-opener for you? Is there anyone you think greatly under-appreciated even by the meager reward system due writers about comics?

SCHWARTZ:

SCHWARTZ: Well, inclusion in the book means I'm pretty sympathetic. As I've said, it's the writers this book is about, not always there subjects. Let's see, Doug's Eisner piece sums up perfectly what I think of the old boy. Gary's interviews, I pinpointed all three of those to say "here's what I love about this guy." Eye-opening: Phelps' close examination of formal innovation in Ditko is killer as is Peter Bagge's hilarious revisionist take on him.

Most under-appreciated? Well, I always feel that I am the most under-appreciated writer in America. Period. I mean, where's my Pulitzer? You might say, "for what?" And I would say, "See, Tom, you don't appreciate me."

The under-appreciated award goes to Fiore, one of the best critics anywhere. Since he only writes on comics (and related movies and TV once in a while), only now is there an opportunity for a wider audience, imo. Thirty-plus years of

Funnybook Roulette is a giant body of work. It's always passionate, too. Only Gary and Bob Harvey can match that long record. Fiore's got a vast knowledge of the medium and the stylistic snap of a Pauline Kael or Lester Bangs. He's not burned out like some critics get. You ever see

Dragnet with Jack Webb as Joe Friday? On

Dragnet you'll see Joe Friday get really steamed and upset over a drug dealer or a killer. Then, next week, he's just as outraged over a guy bouncing checks at a hardware store. Bob's like that! He writes up every comic like it matters -- after all these years. George Harrison or

Fabian Nicieza, he's on the job. So, I give it to him. After I get my Pulitzer, I want him to have one.

But no one is well known as a comics critic yet. There's no

Michiko Kakutani or

Roger Ebert of comics. Any writer you've ever heard of in this book is generally known for something else they do first -- cartoonist, publisher, novelist, comedian, academic, movie or music critic, whatever. I'd say Doug Wolk is the closest to professional comics critic in public recognition.

SPURGEON: Do you read any writers about comics on an ongoing basis. How much of a role does engaging with this kind of writing have an effect on your comics-reading habits?

SCHWARTZ: Despite how I edited this book, my first instinct is usually to read about cartoonists I like. I read your site for news and reviews and stuff and

TCJ. That covers a lot of my fan boy interests. I probably read Doug Wolk more than most because he's in

The New York Times so much. I wish I read him less because I want some of that space! Then Jeet, because our tastes are so similar. On Saturday nights and Sunday mornings I look over the book sections of newspapers on-line and read whoever I come across. I also get

Bookforum and

The New Yorker in the mail, and then the

Comics Comics guys, so whatever they run.

Has it changed my reading? Sure. In the time I started reading

TCJ in '79-80, I wrote my first comics article on

Marv Wolfman's

Teen Titans. In college I did interviews with Drew Friedman and reviewed him and late '80s Bagge and Burns. By the end of college, I wrote a non-superhero piece -- a compositional study of

Carl Barks'

Back To The Yukon for Volume V of the Barks Library. That was a mix growing up, hanging around with

Howard Chaykin who I also interviewed back then, Fiore, Groth, and my own film and music critical reading.

SPURGEON: Will there be a second volume? Can you describe in any way what that might be like?

SCHWARTZ: I don't know, it depends how many copies my family buys of the first one as holiday gifts. One thing that would change is a tightened time frame to an annual or two-year collection. An annual affair might be tough, because I still don't see enough coverage in the MSM, but it's getting better.

Also, as many of the lit guys drift into

Sammy Harkham's

Kramers Ergot and Nadel's

Ganzfeld (I give them the last word in the book), I'd like to look at the art comics movement more. They're making serious comics and breaking into mainstream design, too. This BACC covers the long-form lit model, but literature ranges from fiction and non-fiction to haiku and epic theater -- no reason lit comics can't hit all that.

*****

*

The Best American Comics Criticism, Edited By Ben Schwartz, Fantagraphics, softcover, 280 pages, June 2010, 9781606991480 (ISBN13), 1606991485 (ISBN10), $19.99.

*****

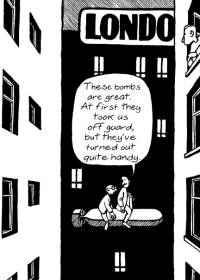

* cover to

The Best American Comics Criticism

* that special issue of

Amazing World Of DC Comics

* from Will Eisner's

Contract With God

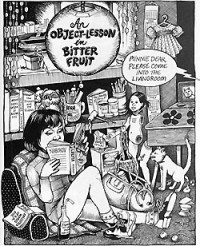

* that

Pacho Clokey mini-comic

* from Fletcher Hanks

* from Frank King

* from Yoshihiro Tatsumi

* from David B.

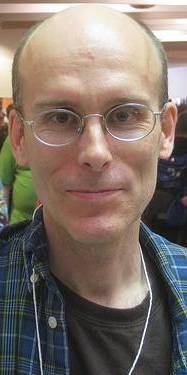

* photo of Chester Brown by Gil Roth

* from the great Phoebe Gloeckner

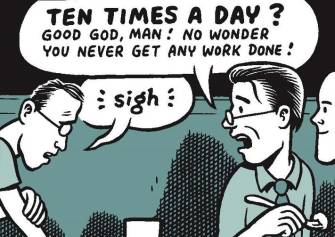

* comics critic Harry Naybors from

Ice Haven

* panel from Joe Matt's

Spent

* art from Steve Ditko

* what a professional comics critic looks like: Mr. Douglas Wolk

* the Teen Titans (below), subject of young Mr. Schwartz's ire

*****

*****

*****