Home > CR Interviews

Home > CR Interviews A Short Interview With Matt Madden

posted January 8, 2006

A Short Interview With Matt Madden

posted January 8, 2006

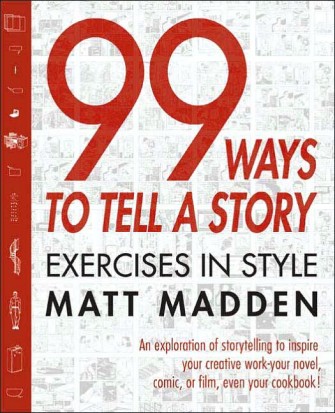

Matt Madden's

99 Ways to Tell a Story is a surprisingly fun read for a book devoted to one-page variations on formal storytelling techniques. It stands even more impressively as one of the few comics really about comics, a teaching tool that is so form-specific you can actually, ironically, pretty easily draw lessons that you can apply to other media. The author of several well-regarded graphic novels and short stories, and an educator himself, Madden is an eloquent spokesman on his work's behalf. I had fun exchanging e-mails with him, one supposes because this is the first time that I've been able to combine reading Matt Madden with the act of talking comics with Matt Madden.

The art that follows are panels from the template comic from which all the variations follow, presented in order.

TOM SPURGEON: Can you kind of remind me of where you are, geographically and vocationally?

MATT MADDEN: I live in Sunset Park Brooklyn and my time is spent teaching comics and drawing at SVA, working on my own comics (occasional anthology work,

A Fine Mess), promoting

99 Ways, and doing occasional freelance illustration and coloring work.

SPURGEON: When we originally talked about an interview, we spoke briefly trying do a variations interview along the same structure as your book. Do you think you might have put a strange stamp on your career with this being your highest-profile work. Are you the stunt cartoonist now, Matt?

MADDEN:

MADDEN: Ha ha, yes, that does seem a bit of a possibility but the idea doesn't bother me much. I don't think it's all that different from the situation all cartoonists often find ourselves in where non-cartoonists friends say "oh you should do a comic about [some not very funny thing that happened to them that day]!!" We're all stunt artists in that sense. I don't really mind being known as the "Exercises in Style guy" because although I do not plan on returning to "Exercises in Style," many of its principles -- repetition and variation, formal experimentation, playfulness -- will continue to be an important part of my work.

SPURGEON: In your estimation - and maybe your publisher's - who is the audience for 99 Ways to Tell a Story

? Students? Fellow artists? Fans of literary exercise equivalents? What are you seeing and hearing as the book rolls out?

MADDEN:

MADDEN: I am continually surprised at what a wide variety of people respond to the book. Certainly I intend for it to appeal to the groups you mention but it can also appeal for example to people who want to learn about comics -- what they are and how they work. I think of my book as in some ways an inductive counterpart to

Understanding Comics, one that will give a reader who has no experience with comics a sense of the possibilities of the medium. I've been surprised at how young readers, say 8-12 year olds, have reacted: my agent's 9 year old daughter confiscated a copy for herself and later demanded another to donate to her school library. Penguin has decided to pitch the book as a creative writing manual and while I'm OK with the idea in general it's been frustrating because it's not a "how-to" book and I have had to fight them a lot on the wording of press releases etc to avoid misleading people; what's more, listing the book as "creative writing" means that it is necessarily shelved only there in all chain stores because their rigid policies don't allow them to cross-shelve the book in the comics section as well.

SPURGEON: How do you think the book is different for you having waited several years before you started doing strips?

MADDEN:

MADDEN: I'm glad I didn't start drawing this in the early 90s when I was still learning how to draw and put comics together in the most rudimentary way. I think I continue to improve as a draftsman and I am a noticeably better artist now than I was in 1998, when I started the project. Luckily, I think I was just competent enough at that time that there is not an alarming discrepancy in drawing skill in the final work. As for the conceptual side of the project, I've felt more confident in that all along and would have probably started earlier if I had better drawing chops.

SPURGEON: You're probably sick of telling this story, so I apologize, but can you describe how you got into learning about Raymond Queneau. As I recall, this went as far as you and some other cartoonists setting up a formal-play group along the lines of his group, am I right?

MADDEN: I discovered Queneau's book when I was working at a book store in Ann Arbor MI in the early 90s, just out of college. I studied a lot of French literature in school but this is a book I came across on my own. It was a few years more before I started hearing about the group he formed in 1961, Oulipo, the Workshop for Potential Literature, which was created discuss the connections between poetic mathematicians and mathematic poets.

Not much later Tom Devlin -- back when he was working at Million Year Picnic -- pointed out

Oupus 1 to me, the first book put out by Oubapo, the Workshop for Potential Comics, an officially sanctioned sub-group of the Oulipo founded by a bunch of the Association cartoonists and the critic Thierry Groensteen. This was very exciting to me: cartoonists more or less systematically exploring ways that constraints can be used to generate comics. Thinking about my own comics I realized that I had been using similar strategies in my own work, so this was like finding a bunch of lost relatives and it helped sharpen my focus in that direction.

A few years later I ended up living in New York and found that both Jason Little and Tom Hart were excited about Oubapo so we decided to start an American Oubapo group (Later Tom Motley from Denver also became involved). The group didn't get much further than a website and a couple of calls-for-entries for comics following different constraints. The most popular and productive one (which I hope many more people will attempt) was to do a 26-panel comic where each panel corresponds in as many ways as possible to its corresponding letter of the alphabet. We got at least ten really good comics out of that, several of which have been published in different venues (Sara Varon's, Roger Langridge's, David Lasky's, and my own "Prisoner of Zembla"). The group is currently more-or-less dormant although there is still an e-mail discussion group. In the meantime I've been elected as an official "US Correspondent" for the French Oubapo group and am slowly getting involved in some of their activities.

SPURGEON: How much time and consideration did you put into the template? Was there anything about the template as you went along that you wish had been different?

MADDEN: It was pretty difficult to come up with the template story -- how do you get inspired to write something that is itself uninspiring and deliberately mundane? From the beginning I knew I didn't want to use Queneau's original story, partly because my goal was to adapt his concept and not just do a cover version but also because his two-part text would be harder to handle in a one-page comic format. So I wanted a non-story of my own, one that would fit on one page.

I brainstormed regularly for quite a while, mostly fruitlessly, but at a certain point I zeroed in on a quasi-autobiographical approach and the scenario I used for the template occurred to me shortly after that. The "autobio" aspect had the additional advantage of allowing me to draw my surroundings, which I think adds a level of visual detail and idiosyncrasy (the small fridge, the spiral staircase, the window) to the basic story, which I was able to use productively in the later comics.

On re-drawing for the umpteenth time I certainly came to regret including both the spiral staircase and the metal window frame, but when it comes down to it I wouldn't have it any other way. There were minor compositional and drawing things that I could have done better and I did consider having one of the final exercises being "Template 2005," which would have been me completely redrawing the template, improving the anatomy a bit, fixing the framing in a few panels (for instance: why did I draw myself almost completely cut off in panel 4?), but it didn't make the final cut.

SPURGEON: Was there any set of variations that were more difficult to you than the others? Was there a general group of variations that was easier?

MADDEN: The homages and parodies were probably the most technically challenging but it was also very rewarding and mostly fun to try and figure out how to draw like Jack Kirby or Jack Chick. The oubapian constraints were some of the hardest things to do (roughly pages 61-79), especially "Inking Outside the Box," which I had originally hoped to model more closely on Art Spiegelman's "Nervous Rex" strip from Breakdowns, and the anagram versions.

SPURGEON: Was there any you abandoned or didn't try?

MADDEN:

MADDEN: When I finished the book I probably had about ten or so extra exercises in some stage of development, and notes for maybe thirty more. Some I could have finished and just didn't make the final cut of 99, but there were quite a few that I abandoned because I wasn't able to crack them; for example: an acrostic version -- where you would be able to read multiple strips in any direction -- which was too hard to work out with such a minimal story; an airline safety card version -- ironic, because it was one of the first variations to occur to me; I also played around with a Chris Ware-style diagrammatic page but wasn't able to make it work in a way I liked. I don't think there were any that were so daunting that I didn't even try them, I made a solid attempt to make all the ideas I liked work.

SPURGEON: Are you going to go back into fiction now that this book is out? What effect has this experience had on how you approach comics generally?

MADDEN: All along I've been working on fiction alongside the Exercises. I started the project at the same time as

Odds Off and have been doing other projects all along, most of which have appeared in

A Fine Mess and

Rosetta 1 & 2. Now that it's done I've been working on a number of short stories -- I have a few ideas for a longer, book length work but I'm not ready to embark on that yet. It's hard to say how much the experience of drawing 99 one-page comics has affected my overall approach. I've never seen it as a radical departure from my other work but rather as a complementary project which allows me to explore comics in a way that conventional stories cannot.

I have always varied styles and approaches in my different comics and in a perverse way I hope

Exercises in Style has gotten that out of my system so that I could settle into a more consistent style so that I don't lose so much time with each comic trying to decide how I'm going to draw it, using which tools, with what kind of composition and rhythm, and so on -- but I know that's impossible because in addition to being attracted to stories like "US Post Modern Office Homes Inc" (from

Rosetta 2), which varied style from page to page, I'm working on a story that will begin in

A Fine Mess 4 which will consist mainly of excerpts from a variety of imagined comics, a bit like

Hicksville or

Ice Haven.

SPURGEON: It's easy to see your book as a argument for comics' versatility, the strength of the medium. Are there other less obvious messages that come out of this experience you would hope people might take away?

MADDEN: There aren't any particular message I've planted in the book for people to find but I do hope there's enough meat in the book for people to come back to it and find new things to react to and think about. My experience talking with readers has suggested that people are generally inspired by the audacity of its creativity and humor regardless of their interest in comics, which is something I certainly hoped for. As for other messages or issues it raises for different readers and critics I'd rather wait and see what happens as the book gets out into the world.

SPURGEON: Has someone's reading of the work surprised you?

MADDEN: I had a woman at a signing recently decline to buy the book because she found it implausible that someone could go to a refrigerator and not remember what he was looking for -- that left me speechless, but other than that nothing has surprised me particularly, although I've been truly gratified to see the variety and richness of reactions readers have had to the book. The appeal is broader than I had imagined and I've gotten great feedback from family friends and neighbors who otherwise don't care for comics. Pre-teens have also been a surprise audience, as I said earlier.

SPURGEON: What's next, Matt, and if it applies, how did this experience change how you're approaching that one?

SPURGEON: What's next, Matt, and if it applies, how did this experience change how you're approaching that one?

MADDEN: I have a few short stories coming out in anthologies soon: "The Running Man Story" appears in a new anthology called

Blurred Vision from a new publisher called Blurred Books which itself developed out of Pod Publishing, the high-end inkjet print gallery run by Kevin Mutch; I just finished my second story for Fantagraphics with the word "fuck" in the title, it's called "Fuck Freely and without Fear!" and it will appear in

HOTWIRE #1, edited by Glenn Head. Otherwise, I am working on a 32-page story -- a star-crossed love story that is a kind of narrative palindrome -- that will make up

A Fine Mess #3. I hesitate to put a release date on that one... In addition to all that, of course, Jessica and I are working on our comics textbook for First Second, which will be out in late 2007 or thereabouts.