Home > CR Interviews

Home > CR Interviews An Interview With Joe Casey (2007)

posted June 10, 2007

An Interview With Joe Casey (2007)

posted June 10, 2007

If he's amenable, I would like to interview the writer

Joe Casey once every couple of years for the rest of the time he and I both work in or near comics. Casey's current projects include the extended meditation on mainstream cosmic comics

GØDLAND, with the artist

Tom Scioli, and

Iron Man: Enter the Mandarin, with artist

Eric Canete. Casey is also I think pretty typical of today's mainstream comics creators in that the work he does anchors a wider variety of interests in television (he's part of the

Man of Action group responsible for the recent animated series

BEN 10), music (he's played in several bands) and film (he's recently directed a movie).

An admirable element of Casey's work is that recurring values of obvious personal importance show up in his comics no matter how out-sized or fantastic they might otherwise be. As we established in

a longer interview for The Comics Journal, one of those issues for Casey is personal responsibility. One that I think comes out in his most recent round of work, which includes

GØDLAND and a second installment of the

Earth's Mightiest Heroes retro-Avengers series, is the notion of psychological trauma as an

expectation of certain vocational choices, what we do to cope when we have a daily existence that makes us feel really, really bad about ourselves.

Other reasons I like talking to Joe is that I think he sees the process of interviewing as a valuable thing in and of itself, and he's practically unfazed by any stupid, rude notion I'll put on the table.

*****

TOM SPURGEON: What do you know now about writing for comics that you didn't know five years ago?

JOE CASEY: Heh... talk about a loaded question. I think, at this point, the language of comic books is completely second nature to me now. I've written enough that the basic semiotics involved just seem to flow without effort. Now I don't mean to suggest that, just because I know the language, every comic I write now is great, chock full of skill and brilliance and perfect in every way. Far from it. But telling a story using the medium is so ingrained now, it's hard wired into my brain. The trick now is to continually challenge myself and find areas of the craft that feel new and different to me. It gets tougher and tougher, because there's not a lot of techniques I haven't at least tried. But, for better or worse, I do think I found my voice and so these days, it's just about refining it as best I can. I'm always learning.

SPURGEON: Two years ago I watched you do a couple of panels at San Diego. You were at the center of the Image panel, and kind of off to the side of the Marvel one, and I thought that sort of reflected where you were at the time. How do you feel about where you are in a career sense right now?

CASEY: Let me put it this way, if you catch me on a panel this year at Comic-Con, I'd be shocked. Having said that, I'll probably do the Image panel, because I'm really just representing myself there. Plus, it's very low key (as you saw last year). But I've got a very "been there, done that" attitude to a lot of the

accoutrements of a professional comic book writer's career. I'm ten years in this game, Tom. I've experienced the ride as both boy and man. At this point, I'm only interested in writing good comic books, fun comic books, and letting my creative juices flow where they will. You can't hold onto these things too tightly, you'll strangle them. So, when it comes to my career, I try to tone down my Type-A personality and just try and do good work. It's actually interesting that you made a distinction between the two panels and the two companies' place in the comic book landscape, as if there really were a "mainstream" within the publishing hierarchy. I suppose there is, but I don't really make those distinctions any more. It's all comics to me.

SPURGEON: You did an autobiographical comic book story I think about five or six years ago where you kind of stepped back and saw yourself really working hard and almost lost in your work. How much of your time is spent on comics now? How much time is spent on other writing?

CASEY:

CASEY: I'd say about one-third of my time is spent writing comic books, which I guess is just about right for me at this point. I've got family obligations now that have come to the forefront, and obviously I've ventured out into other kinds of writing. With Man Of Action, having created

BEN 10 opened quite a few doors in animation, and I'm in post on a film I wrote and directed. If there's any work I get "lost" in now, it's probably the film... mainly because it takes so much focus and energy to make a film. At the same time, it's also been the most rewarding creative experience I've had in the past few years, so naturally I'm going to gravitate to the thing that engages me the most. Having said that, I love comic books too much to ever give stop doing them. Those are skills that were too hard won to ever put down.

SPURGEON: What was the experience like working with the later Avengers

material in your Earth's Mightiest Heroes

miniseries as opposed to the early material? What do you feel changed in comics between the first period, 1963 or so, and the second, 1966-1967?

CASEY: EMH2

CASEY: EMH2 was the series I was really looking forward to writing, even as I was writing the first series. The

Roy Thomas era was one I was more familiar with (mainly because the

Stan Lee stories -- especially the first year of

Avengers -- weren't the most compelling comic books he'd ever written). I tried to approach

EMH2 in the same manner that Thomas wrote his stories... more soap opera, more of a potboiler, more character continuity... all the things that made Thomas' run crackle with a specific kind of energy. Of course, he also had

John Buscema,

Sal Buscema,

Gene Colan,

Barry Smith and

Neal Adams drawing his run... always a bonus.

I think, if you're comparing Stan and Roy, it comes down to this... Stan created the universe, but Roy was the first writer that really got to play in it. That's the difference. It's obviously rewarding to create something... but it's also great fun to play. That's basically the reason to write

anything for Marvel or DC... because you get to play.

SPURGEON: Why can't anyone seem to write Iron Man?

SPURGEON: Why can't anyone seem to write Iron Man?

CASEY: The thing is, anyone

can write Iron Man, if they meet certain criteria. You have to 1) know how to write superhero comics, 2) know the character and its history, 3) have some insight into the character and its history, and 4) Marvel Comics has to hire you to write Iron Man. In a way, the idea of quality doesn't

have to enter into it. It does for me, but those are my own personal standards. Actually, the only one that really matters out of that list is #4. For me, Iron Man is a childhood favorite (especially his appearances in

Avengers and the Michelinie-written runs of his own book), so I take that gig extremely seriously (in the sense that I'm serious about having fun with it). Just like my work on the

EMH mini-seires, I hope the die hard Iron Man fans enjoyed

The Inevitable series I did with

Frazer Irving and that they'll dig the IM/Mandarin mini I'm currently writing (with art by my former

Mr. Majestic collaborator, Eric Canete).

SPURGEON: Tell me more about the film project. In fact, tell me as much as you can about the film project.

CASEY: Honestly, there's not much I want to say... until it's finished and ready to be seen (which will hopefully be in the next month or so).

SPURGEON: Why are you reluctant to talk about it?

CASEY: C'mon, how many times have we seen guys announcing an option or some nebulous Hollywood deal, puff up their chests and soak in the envy they assume we're all feeling, and then nothing happens? The list is long and tedious. I did an end run around all that bullshit by simply going out and making a film. I went the indie route. The thing is, I'd rather create than talk about creating... which absolutely makes me an anomaly in practically every field of entertainment, including comic books.

The experience itself was amazing. Putting together the production, assembling all the pieces to make the thing happen, then working with the actors... it was all great. The shoot was blessed from day one, no major disasters, we made all our days, etc. Post has been kind of a drag, because you scale back to a small crew again and I really miss all the folks from the shoot, but I think the end result will be worth it. Writing comic books is a lonely life. Making a film is an extremely social endeavor. Sometimes it's frustrating, because of the sheer size of a feature... but overall, the positives absolutely outweigh the negatives.

SPURGEON: Outside of your own perspective ten years ago to now, how do you feel about the way your friends and peers are treated in the industry? It seems to me you've reached that point where you're all no longer on the same page as up and coming guys... so is it a good place to work? Do you feel like your generation of creators is being treated well as you head into your second decades?

CASEY:

CASEY: I think I've seen every kind of career trajectory play out around me over the past decade. I don't necessarily think there's a blanket statement I could make about the "treatment" myself and my peers have received. Everyone ultimately receives the treatment they deserve, and it's always a case-by-case basis. I also have to be completely honest, I've gotten to the point where I'm fairly disinterested in the "moves" that I see being made. Except for my friends in the business, where I have an interest beyond their careers, it's just kind of... boring, really. To hear publishing reps -- and even creators -- talk about their participation in company-wide crossovers like no one's ever thought of doing this before is laughable. It's

all been done before!

Marvel in 2007 is no different than Marvel in 1997 or 1987. Same with DC. It's about crossovers and events and gimmicks. That's what mainstream publishers are

supposed to do. But just don't act like you thought of it or that you're doing it better than it's ever been done before. I guess I have been

in the industry long enough that I now see the patterns pretty clearly... I've experienced the cycles myself.

SPURGEON: We've seen exponential growth and untold money and attention pouring into comics the last five years. Are creators sharing in that wealth and attention to the same extent it's coming in. If not, why not?

CASEY: Is this a trick question?

SPURGEON: I hope not.

CASEY: Creators will never share the wealth in a manner that anyone could classify as "fair." We've talked about this before... creators get screwed. Artists get screwed. The model for the industry has always been that way, and probably always will be. We do get the attention, so if that's what you're after as a creator, to see yourself in

Wizard Magazine or be mentioned on

G4TV, then I suppose it's all good. But having "fame" is one thing... having power is another. Fame is easy. So easy, I can't even tell you. But getting some power is a much trickier thing, and in the long run, is much more valuable to a creative person. And I mean

real power, not the power I see people trying to trick the rest of the world into thinking they have.

SPURGEON: But certainly the last two periods of growth led to increased benefits for creators, particularly those working mainstream American comic books. The 1980s Shooter-driven growth provided creators greater benefits through a royalty system. The 1990s Image period, for all of its excesses and horrors, provided some cartoonists with previously unheard-of financial opportunity. Has anyone benefited at all in this new period? Who? Where?

CASEY: My feeling is that we're now operating in a landscape that's pretty wide open at this point. How a creator benefits from that all depends on what they ultimately want to get out of comics. Look at

Frank Miller... not only did he co-direct, but it was an adaptation of his own comic book.

Dan Clowes is another example of a creator who shepherded his own comic book material into new media. So, the walls have broken down significantly, just in the past five or six years.

When I broke into the field as a professional, comic books seemed so off the cultural radar, it never occurred to me that I could parlay the work in one field into work in another. Now, here we are and not only are comic books a main source to be exploited in Hollywood and other media, the creators themselves often have the clout to be intimately involved in the translation of their creations. We're been taken much more seriously for a number of reasons, not the least of which is the fact that we often control our creations, we own them fully. And ownership is everything in Hollywood. Y'know, I suppose the real trick is not falling out of love with the medium that provided you with all these new opportunities in the first place...

SPURGEON: In our interview for The Comics Journal, you expressed a level of dismay for the fundamental lack of respect for the professionalism of creators you'd experienced during your years as a freelancer. Has that changed, or are you still treated poorly? If it has changed, how have you noticed it to change and why do you think it has?

CASEY:

CASEY: Well, I think it's more that

I've changed. I tend to expect less and that tends to make it easier. Or, at least, I don't leave myself open to abuse. I also seek out better people to work with. I'm pretty happy with the editors I've worked with at Marvel over the past few years. They've been pretty professional with me and that's all I could ask for.

The fact is, freelancers are treated "poorly" only when they open themselves up for that treatment. I've done it in the past, and hopefully I've learned my lessons. If a publisher offers you a shitty deal, don't take it. After ten years of writing comics and getting my work out there... there's no one project that's make-or-break with me anymore. Sometimes people I work with don't quite get that, and have tried to somehow hold me hostage by what they think is my own burning desire -- that "I'll do anything"-desire" -- to see a project come to fruition. But I'm just not desperate like that, and I have no intention of bending over for

anyone just to get any one project out there. Besides, I've worked long enough and hard enough that I have plenty of options for whatever I end up wanting to do. Right now Image has been a real home to me in the projects I've had a genuine desire to do. Couple that with the fact that they have the best deal in the industry and there ends up being no reason whatsoever for me to have to take shit from anybody.

SPURGEON: That's kind of depressing in its implications, though, Joe, isn't it? Aren't you basically saying that comics is an abusive, exploitative system by nature and the way to get around that is to a) not give a shit and b) take enough crap for long enough you get in a position where you have other options? That's like the G. Gordon Liddy school of creator's rights.

CASEY: Without seeming

too glib about it, welcome to the entertainment business. There is a fray and you can place yourself above it all, if you so choose. Especially after you've been in it for a while and gotten a taste of it (or a distaste, as the case may be). I'm certainly not suggesting my approach to the business is the best approach, it's just the one that's worked out for me and my sanity. Let's be real here... fundamentally, exploiting artists is what every facet of the entertainment business is all about, including comic books. The word "exploit" can be used in its most negative connotation, or it can simply be the word that describes what goes on. Both can apply, depending on your point of view.

The thing is... artists can exploit the entertainment business right back. When I write for a mainstream publisher, am I exploiting them and their considerable presence in the

Direct Market to get

my name out there more? Sure I am. Are they exploiting me by paying me less than I'm worth for a product they'll get a lot more in return for? Absolutely. I think it's only depressing when you have a different view of what the entertainment business

should be. Particularly one that somehow

owes you something. I don't have that view, and to do the work I enjoy doing, I need to master the system that's there, evolve when it evolves, bob and weave when it throws another punch. I'm not depressed about it at all, really. You can yearn to change the system, but you have to realize going in that the system doesn't

want to be changed. And at this point in my life, there are other things -- other people -- much, much closer to me that I can actually have a direct effect on, where I

can affect real change, so that's where I tend to concentrate those particular energies. I hope no one thinks that I'm somehow ducking a cause... but it is my life, isn't it?

SPURGEON: What's the single thing that you and other pros talk about that readers would be surprised to hear is something on your minds? Is there something in pro-bitching zeitgeist we can get out there on the table for everyone to consider?

SPURGEON: What's the single thing that you and other pros talk about that readers would be surprised to hear is something on your minds? Is there something in pro-bitching zeitgeist we can get out there on the table for everyone to consider?

CASEY: No, it's still the same petty bullshit we're always talking about. It is funny to hear some of my friends bitch about the things

I used to bitch about. Actually, this may not be so surprising to hear, but I get a kick out of it... pros can look at other pros' careers and know instantly ways to "fix" them. But their own career... no clue whatsoever. It's easy to look at someone else's situation with an analytical eye and really come up with solid solutions or even just valid insights but it's terribly difficult to turn that eye inward. And, of course, the last thing pros want to do is take the career advice of fellow pros. I've seen readers on the message boards try to play career counselor, but they never quite get it like we do in the trenches of the industry. You could name me five writers or artists and I could instantly tell you what they should do next to further enhance their careers. But for me...? Hell, I feel like I'm just winging it most of the time. I'd never be able to analyze my own career with such certainty.

SPURGEON: How has working on BEN 10

changed the way you view how comics work?

CASEY: BEN 10 has been a nice paycheck. One day I'll actually watch the show.

SPURGEON: What can comics offer that film and animation can't?

CASEY: Comic books at their best have an autonomy that no other medium can provide. Now, I should qualify that statement... it's not complete and total autonomy. But it can be significant. Especially for a writer/artist/cartoonist. I'll never have the kind of autonomy that guys like

Kyle Baker,

Jeff Smith,

Jim Mahfood,

Erik Larsen or

Evan Dorkin have. Those guys don't need anyone to make comic books, which is fantastic. I would think that, in that respect, animation, film and TV could learn more from comic books, not vice versa. If anything, comics -- the industry, not the medium -- have learned the wrong things from Hollywood, in terms of behavior. But, that's how it goes, I guess.

SPURGEON: You mentioned the notions of playing a couple of times. If you and other are writers find the greatest benefit in working in a setting like the Marvel Universe in that you're getting to play, how come so many of those comics are fussy and depressing?

CASEY: Well, I can't speak about how other writers get their rocks off when they splash around in the Shared Universe Pool. I only know what

I get out of it. And I honestly don't read too many Marvel comics so I can't attest to how fussy and depressing they are. I guess it stands to reason, since most of the writers working at Marvel were probably '80s readers and haven't shaken the

Moore/Miller influence yet. Hell, that influence has infected film and television, too, hasn't it? Talk about fussy and depressing!

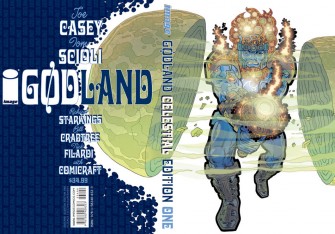

SPURGEON: How has wanting to have more fun in your work changed the way you approach your work? Are you as concerned with things like the development of theme or saying something through your work? Do you have aspirations for work like GØDLAND

, that they achieve a certain level of greatness or quality?

CASEY: I suppose my main aspiration these days is to get rid of as much self-consciousness as possible in the writing. With

GØDLAND in particular, it'd be real easy to get caught up in the "bigness" of the ideas... cosmic gods and the origins of the universe, etc. It could easily fall into some trap of self-importance that, for me, would really undercut the fun of the whole thing. Superhero comic books are entertainment, first and foremost. What I get out of writing them personally is my business. What any reader gets out of reading them, above the pure entertainment value, is their business. It's not that my expectations are low, but I've already gotten off just getting able to write the thing. Anything past that is icing on the cake. But it's about the act of creation, the sheer fun of making shit up.

SPURGEON: Do you think GØDLAND

has been interpreted unfairly and perhaps dismissed as a Kirby pastiche?

CASEY: Tom's art invites those comparisons. If anyone has dismissed the book on that basis, that's their choice. I can say without question that it's a lot more than a Kirby pastiche.

SPURGEON: How would you articulate your wider aims with the series?

CASEY: I may sound like a broken record at this point, but I've always seen

GØDLAND as a thoroughly modernist series. Plus, Tom and I both know we'll never be as good as Kirby, so why even try. He did his books, we're doing ours. He played in the sandbox he created, we're doing the same. Tom's use of the Kirby style is nothing more than the use of a specific comic book language.

GØDLAND was created to speak in that language.

SPURGEON: One of the interesting things about GØDLAND

for me is that it's reframed a certain kind of mainstream comics as a 20th Century artifact, as in, say, the way they approach Armageddon-like threats from the sky. What does a comic like GØDLAND

say about right now that might be different than how these stories were used in the 1960s and 1970s?

CASEY: I think I'd take what you said one step further... those "Armageddon-like threats from the sky" are really our future that's just come a' knockin'. In the past, that particular dramatic trope was representing things that were much more sinister in nature... the enemy beyond our shores, for instance. More than anything, I think the book demonstrates the ignorance of humanity. How we're fearful of change, how we hate what we don't understand, even as it comes from within ourselves. I'd hate to get too deep about it, but the real antagonist in

GØDLAND is a humanity that doesn't embrace the future.

SPURGEON: In your first

SPURGEON: In your first Earth's Mightiest Heroes

series, you did a nice job unpacking the Iron Man character in terms of his feelings of responsibility towards holding together a lot of disparate threads, some of which involved doing things that are a lot less gratifying than giving someone the finger and walking away. In this latest one, I thought you provided a nice snapshot through Giant-Man of the horrible psychological pressures that must face people constantly undergoing life or death pressure. Would you say this is an extension of your interest in vocation and adulthood? Do you realize you're exploring this kind of thematic material as you write?

CASEY: I would say that kind of stuff is in there somewhere, although for the most part it's probably as unconscious a thing as it ever was. With the

Hank Pym character in

EMH2, I approached it like this... there's the man you want to be, and then there's the man that you truly are. It's a question of self-image. Can any of us be completely honest with ourselves about who we really are? It's something I struggle with quite a bit, actually. Especially in a field like comic books, where you're thrust into branding yourself as a part of the normal career path. The brand may not be reality, but how we wish others to perceive us.

With Hank Pym, this was a character that I felt had a lot of integrity. He wasn't pretending to be a greater hero than he was. But, eventually, being that normal and well-adjusted in a world of gods and monsters will get to you... and Hank Pym cracked. In a way, his persona as "Yellowjacket" was a subconscious commentary on just about every other superhero he'd ever encountered over the years, from the bluster of

Thor to the wise-cracking of

Spider-Man and so on. Now, add to that the fact that my ideas on what "adulthood" is tend to morph and change over time... I guess I can't help but to explore that in the work.

The other thing about the Avengers is how, when I was reading the book as a really young kid, I always associated that particular team with the concept of being an adult. These were adult characters, often with adult problems, talking to each other as adults, doing a job (the Avengers got paid a stipend, y'know). I honestly felt like I was sneaking a peek into the adult world. If anything, that's a testament to the writers at the time --

[Steve] Englehart,

[Jim] Shooter,

[David] Michelinie -- not writing down to their audience, which at one time consisted mainly of children. Hard to believe now... when it seems like hardly any kids are reading Marvel and DC comics.

SPURGEON: Your career is marked by long runs on stand-alone titles, while the industry is becoming increasingly driven by event books and crossovers. Good idea or bad idea for mainstream comics to move in that general direction? Why?

CASEY: I actually don't mind event comics or crossovers... as long as they don't suck. Unfortunately, that's rarely the case. It's when retailers get fooled into ordering shit comic books because they think they "matter" to the event that I get a little nervous about the future. It's a real chicken and the egg situation... what comes first, retailers' desire to make a buck... the publishers' desire to exploit that fact... or the readers' desire to be completists? And do those desires overlap from group to group? I think they do... which makes it even more of a fucking quagmire.

SPURGEON: Your run on Adventures of Superman

was distinguished by never having the lead throw a punch. This is the same tactic employed in the recent Superman movie. Would you like to apologize for that film sucking?

CASEY: All I can really say about that is... the Superman I wrote was happily married. To a woman. Nuff said.

SPURGEON: Wait, are you suggesting that heterosexuality is a crucial component of the Superman myth?

CASEY: I wouldn't necessarily know the answer to that, my friend. It's been a while since it was my job to think about the crucial components of the Superman myth. Ask

Dan Didio or

Paul Levitz that one... and let me know what they say (in case I ever write the character again).

SPURGEON: There seems to be a disconnect between the way you talk about your

SPURGEON: There seems to be a disconnect between the way you talk about your GØDLAND

work as play and fun comics and the way you're presenting that work in a massive hardcover out this summer, complete with testimony about the work in essay form included in the book. Does this reflect some sort of ambiguity you have about creating serious works of meaning, or doubts that you have about your ability to the same? All deflective bullshit aside, Joe, how good do you think this work is? And if you don't have a high opinion of it, why should a reader?

CASEY: Don't get me wrong, Tom, I think

GØDLAND is the greatest thing since sliced bread. But that opinion comes from my own personal experience writing the thing. It's as close to the thrill of being a kid, making up comic book stories on the floor of my bedroom, when I was just doing it for myself. Having said that, I'm extremely proud of it, and of the fact that it's lasted this long. And the work that Tom Scioli, colorists Bill Crabtree and Nick Filardi, and designer

Richard Starkings have done truly

deserves this Celestial Edition format. As [Howard] Chaykin once said, it's not going to replace sex, but it's definitely work that I'd put up there with the best stuff I've done.

Besides that, I have to admit that while I'm gratified that Image thinks it's worth putting out this hardcover, it wasn't my idea to do it. Nor was it Scioli's. The thing is, we're now in a market where hardcovers are a viable publishing option. Marvel puts out hardcovers like they're going out of style... but that's because there's a market for them. So, why shouldn't

GØDLAND compete in that market, if we're given the opportunity? Besides, you wrote such a great essay for it... people have to be able to read that in a permanent edition, right?

SPURGEON: I'm always writing for the trade, Joe. Hey, say you're given an opportunity to jump in the wayback machine and and travel back in time to have a business lunch with the 1998 version of Joe Casey, but you're only allowed to give business advice. What would you encourage him to do differently?

SPURGEON: I'm always writing for the trade, Joe. Hey, say you're given an opportunity to jump in the wayback machine and and travel back in time to have a business lunch with the 1998 version of Joe Casey, but you're only allowed to give business advice. What would you encourage him to do differently?

CASEY: Oh, man... I don't know. That's a loaded question. My first though is that I wouldn't want to fuck anything up for Casey '98, because all the shit he'll/I'll go through gets me to Casey '07, which ain't a bad place to be. Even being a loudmouth got me to places I never thought I'd get to, so I don't know if I'd even dissuade him/me from doing that. I don't have any serious regrets, so it's weird thing to consider. Plus, there's always the possibility that Casey '98 would never agree to having a "business lunch" with an old fuck like Casey '07. Interesting question, Tom... do you happen to possess a

Flux Capacitor that the rest of us don't know about? Oh, wait... you said "wayback machine." My apologies,

Mr. Peabody.

SPURGEON: How can that be a loaded question or even an interesting one when your answer is a serene "I wouldn't change a thing"? What are you reluctant to say?

CASEY: Well, c'mon... it's loaded because I could tell Casey '98 everything he/I would need to know to become King of the Fucking World, couldn't I...? And I'd be tempted to, believe me. Hell, the pitfalls of a comic book career would be small potatoes when it comes to that kind of power. But then, that would expose the inherent megalomania that I try so desperately to lock down. Ultimately, I do take a Captain-Kirk-in-

Star-Trek-V approach to life: "I don't want my pain taken away! I need my pain!"

SPURGEON: Has the pleasure you derive from the act of writing changed in the last 10 years? How would you describe how you feel about the physical act of putting work onto paper at this point in your life? You talk in terms of really busy times, fully absorbed in your work. Is that an intensity you can maintain when you get older?

CASEY: I think I'm becoming more efficient in the time I spend at the keyboard. I have more outside concerns now than I did even two years ago, so it's less likely that I want to sit here, 24/7, like I've done in the past. I sometimes miss the workaholic I used to be, because it was a great, gratifying period to be so into the work I was doing. Just completely immersed in it. But you have to move through a period like that, you have to evolve beyond it. I've had to learn how to let other things take precedent in my life. The benefit of that, I think, is that it begins to inform my work in new and interesting ways.

You pointed out that a lot of my work related to a search for and an exploration of adulthood. Of maturity. Of being a grown man, not an overgrown kid. I'd never disagree with that, I think it's true. But, I think I'm here now... more than I ever imagined I would be. Even working on the film -- which is as immersive a project as I've tackled in the past few years -- doesn't take my focus away from my family like it might've a few years ago. At least, I hope it doesn't. And, if it does, I get frustrated and even angry about it. That's certainly a big change from before, when I tended to use work to try and escape from those things.

Does that sound too self-aware? Yikes...

SPURGEON: During our Comics Journal

interview a few years back, we talked about the fact that a writer you admired, Mike Baron, wasn't working a lot at that particular point in time. Now that you're old enough we can point to established, working writers who came after you -- Robert Kirkman, Matt Fraction, for instance -- do you ever worry about being one of those writers who one day no longer gets work? If not, what is it about you that you don't think this will happen? If so, are you comfortable with that notion?

CASEY:

CASEY: Well, I think something that might've been seen as a career detriment has actually turned out to be an advantage for me in the long term... which is that no one, neither editors or fans, can completely pin me down as to what I "do". If you took something like my work on

[Adventures of] Superman or

Cable and compared it to something like

Automatic Kafka or

GØDLAND, I don't think you'd think it was the same writer. I may have a voice, but there's not a style or a genre that I've been pigeonholed in so it's kept me out of being lumped in with whatever fads might have come and gone -- in the mainstream at least -- over the last decade. That's kept me pretty viable as a writer. Also, I've never been a top guy, the Hot Shit for this year. And I'd rather be tenth in line for twenty years than first in line for one.

I'm running a marathon here, not a sprint. So there's that... but there's also the success that Man Of Action is having with a show like

BEN 10, which is just the tip of the iceberg for us. That sense of not having to completely depend on writing comic books -- not for the mainstream publishers, at least -- gives me a lot of freedom, a lot of room to maneuver in my career. And I think I've been enough of a student of my heroes in this medium to learn from their mistakes as best I can. They made their various choices and sacrifices and mistakes so that I don't have to repeat them.

Having said that, it's beginning to look like I'll have more mainstream work in the coming year than I've had in quite a while. That's come mainly from being fairly precise about what I want to

do in the mainstream, and going after those projects with some degree of tenacity. Writers fall out favor when they start to expect that publishers and editors will just automatically keep offering them work, and that it'll always be like that. That's just setting yourself up for a rude awakening. You can't coast when you're dealing with the Big Two. You can't depend on a corporation's generosity and your certainly can't count on their loyalty. If you want something from them, you have to get in there and fight for it... creatively speaking. I've never shied away from that process.

For instance, this mini-series I'm writing for Marvel,

Iron Man: Enter the Mandarin, is a project I brought to

Tom Brevoort, pretty much as a cold pitch. I brought on Eric Canete as the artist. It wasn't something that Marvel had lying around, in search of a creative team. The series wouldn't exist if I hadn't thought of it first. I kinda' dig that. It all came down to my own initiative. And had they not accepted and approved the project, I wouldn't have been too broken up about it. That's just how it goes. There's always another idea.

SPURGEON: You mention a few questions back that you enjoyed the act of creating

SPURGEON: You mention a few questions back that you enjoyed the act of creating GØDLAND

because it took you back to being a kid and making comics on the floor of your room. I was thinking of the fact that you created Stacy X, one of the least-liked characters in modern superhero history, and the two acts of creation may make you uniquely qualified to answer this question. Given the talent and resources that have been put into superhero comics, why aren't there more successful, iconic characters created? Is it that it's a genre that's suited for child-like outlook? Because I don't think of Jack Kirby as child-like. Is it a restrictive genre? A poorly utilized one?

CASEY: First of all, let's not gang up on poor Stacy X. She was an honest character before other writers fucked her all up. At least she got people talking. I do think you might have something close to a point there... to really create something that breaks through barriers and becomes iconic is, to me, an instinctual thing. I always felt that's how Kirby worked... completely on instinct. You can't over-intellectualize something like that. And I'm not sure you can do it purposefully. I can't imagine Superman was created to

be an icon. Or Batman. Or Spider-Man. Comic books is a medium of accidental icons. And I think the dominance of DC and Marvel superheroes for the past 50 years pretty much answers your question about whether or not its a restrictive genre.

SPURGEON: You've had some difficulty throughout your career with your endings. Do you have ending in mind to your professional career? What one thing would you like to accomplish -- even if it's just doing comics consistently throughout -- before you go?

CASEY: There's no such thing as retirement for writers. At least, not as I see it. It's much more than a job, it's a life. And a "career" is generally a byproduct of simply doing the thing that you're inexplicably compelled to do, the thing that you'd do for free anyway. It's amazing to me that I've been doing this professionally for ten years now. I followed my bliss and it actually worked out for me. It's the longest commitment I've ever had to

anything...! At this point, I guess I don't think much about what I want to do for the breadth of my career... I spend more time just thinking about what I want to do

today.

SPURGEON: Why are there so many ugly people in the comics industry, Joe?

CASEY: You mean, physically? Or spiritually? That's a good question... even if it's a rhetorical one.

SPURGEON: When was the last time you were really, really frightened and why?

CASEY: Hmmm... probably something to do with a personal family situation that your readers would no doubt find very boring.

If you're alluding to what has frightened me, comic book career-wise... I wouldn't have a good answer for that, either. First of all, there's nothing or no one in comic books that's worth being scared of. I used to think there was such a thing as "making it" in the comic book field. I guess it used to stir up some fear and anxiety in me that I would never make it, whatever that meant to me at the time. Now I see that you don't "make it" in comic books. You never cross a magic threshold of success where you can kid yourself that all your problems are gone. Has Alan Moore "made it"? DC still pulped his book when they felt like it. Has Frank Miller "made it"? I guess we'll find out when

his Batman-vs-Al-Qaeda book comes out. It's the fallacy of fame, isn't it? So anyway, once I realized that, so much anxiety I'd had about the business just went away.

Wait, I take that back, Tom... your question about Superman and heterosexuality frightened me a little.

*****

*

Godland Celestial Edition, Joe Casey and Tom Scioli, Image, hardcover 360 pages, July 2007, 1582408327, $34.99

*

Avengers: Earth's Mightiest Heroes Vol. 2, Joe Casey and Will Rosado, Marvel, hardcover, 192 pages, July 2007, 0785118519, $29.99

*****