Home > News Story and Obituary Archive

Home > News Story and Obituary Archive Bill Blackbeard, 1926-2011

posted June 6, 2011

Bill Blackbeard, 1926-2011

posted June 6, 2011

Bill Blackbeard

Bill Blackbeard, the great archivist of 20th Century comic strip material and a man as important as any to modern comics publishing,

died on March 10 in the Northern California nursing home where he made his home. He was 84 years old.

Blackbeard was born in 1926 in Lawrence, Indiana, a community in Indiana's Marion County that remains distinct by name and nature from that area's dominant Indianapolis, and was certainly so back then. His parents were small business owners that moved west to Newport Beach, California while Blackbeard was still a child. He was educated locally, graduating high school in 1944. Blackbeard served in World War II in the 9th Army, participating with distinction in the European Theatre in France, Belgium and Germany. After leaving the Army he attended Fullerton College on the GI Bill. He studied history and American literature, appropriate subjects considering what was to come, but never graduated.

Blackbeard had continued into adulthood a childhood practice of collecting comic strips. Strip collection was a not-uncommon practice for fans of newspaper strips in the pre-War glory years. This was a time where very, very few comics works were reprinted in any form and thus yesterday's offerings could meet a variety of final fates, nearly all of them dire: consigned to domestic use around the house, or employed as raw material for play, or used to start fires in fireplaces. What newspaper comic strips weren't was formally recycled. This gave a collector with Blackbeard's perhaps unique appetite for a wide variety of strips, a hunger focused on the strips themselves rather than any specific offering, a foot in the door in terms of piles of newsprint to be teased from garages, attics and storage bins. It was an encounter with just such a collection containing newspapers stretching back to the years before his birth that first enthralled Blackbeard. So began a lifelong war between the late archivist and the destruction of print, a battle he would fight first hand-to-hand and later on an international platform.

It is because of Blackbeard and a few fellow travelers that it's hard to conceive of the notion, but there was a time in the battle between the newspaper comic strip and oblivion that you could make a case that oblivion on a mass scale stood a good chance of eventually winning out. Newspapers themselves and local libraries kept copies of printed issues, but there were always storage space issues with the former and exposure issues with latter. As radio and television media continued to surge in the 1940s and into the 1950s, markets served by several newspapers -- and several sets of comics -- began to shrink into double- and single-paper cities, with only intermittent attention paid to saving the fallen publication's physical record. There was the further matter of the quality of the material being saved. Fans less mature and more focused on the obsessive joys of owning a run of a certain strip as they saw it appear daily might not pay attention to the way the post-War publication might trim the edges to have more features fit. Judging from the relative quality of Blackbeard's future archives, his holdings tended to represent the best copy of a strip available in a way that could not have been an accident. Blackbeard was that rare reader and enjoyer of comics with wide enough taste so that a great deal of material was saved, but also maintaining standards as to what he was reading and enjoying so that the reputation of certain strips would be protected and promoted above others. He was clearly the ideal man, the only man, for the job of his lifetime.

Hoping to parlay his collection into a book about the comic strip form, the 1960s saw Blackbeard's archival efforts intensify. Published-strip collection -- clipping individual strips right out of the paper or the rarer choice of keeping sheets of the funny pages intact -- wasn't just important for the fact that it could be left to the self-actualized efforts of a Bill Blackbeard, it was in many ways the only dependable resource for gathering together the art in any format. There did not exist the original art market that exists today for comic strip material, which frequently meant that the originals were given away or otherwise hastily disposed of, making in most cases an unreliable archive for future collection. (In contrast, it's my understanding that the recent

Bloom County books from IDW made extensive use of Berke Breathed's originals.) Syndicate tearsheets and similar material devoted to the publication process have become a source for many collection efforts in recent years, but particularly with the older strips they fail to cohere into a dependable resource because of their own versions of the problems facing both newspaper/library holdings (syndicates were institutions that frequently went out of business) and original art (such hard-copy records weren't valued within many of those companies). It is in no way a stretch to suggest that the archival comics efforts of the last 35 years would, without Blackbeard, be a vastly spotty, arbitrary and much more limited affair.

Blackbeard's foundational acquisition, and a turning point in his career, came in I believe the early 1960s when he secured from the Library of Congress a number of newspapers from their warehouses that they were in the process of scanning for microfilm and destroying. Not only did this yield truckloads of material for Blackbeard's holdings, but it provided a strategy to pursue in securing more material and a cultural movement to fight against. Since at least the early 1940s, libraries had been collecting newspaper material with the idea that it would have to be eventually scanned into microfilm or other medium because of storage concerns and the inevitable decay of the material. Blackbeard quickly seized on a counter-narrative: that the printed material wasn't decaying to significant extent except as it was haphazardly exposed to light, that a great deal of this material's power would be lost to a form that did not feature color or a way to capture delicacies of line, and that this was going to happen mostly because the libraries had invested in a way of thinking that said it was going to happen, any evidence to the contrary be damned. Blackbeard would eventually find an eager recipient for his thoughts on the matter in the author Nicholson Baker, who had discovered and written about the destruction of printed material in San Francisco's libraries using versions of the same specious arguments that Blackbeard had now spent decades inveighing against. Blackbeard appears as a kind of combination wise man, spiritual teacher and desert prophet in Baker's award-winning 2001

Double Fold: Libraries and the Assault on Paper (and the

New Yorker pieces that preceded it), about the latter stages of a movement against keeping and cherishing print that Blackbeard had witnessed three to four decades earlier. Its main title comes from a test for paper that Blackbeard had taught Baker.

Blackbeard initially used the knowledge he had gained about the microfilming and disposal process to set about securing piles upon piles of newspapers that would otherwise have been tossed out. He had enough strips now that his collection could now take on systematic aspects, finding complete runs of strips in multiple newspapers, for instance, or favoring a higher-quality run over one that was not printed as well. In 1968, Blackbeard founded the San Francisco Academy of Comic Art, a non-profit devoted to his endeavors with newsprint. It seems as if the Academy had equal value as a place to house the material being gathered, and as a construct to organize the endeavor in a way that was as financially advantageous as possible -- never all that much, but enough to apparently pay some of the bills accrued. That building and its massive, increasingly legendary holdings remained a beacon of saved newsprint until its closure in 1998.

Blackbeard never wrote the systemic history of the field that had intensified his collecting efforts, but he contributed to something far better: a foundational and

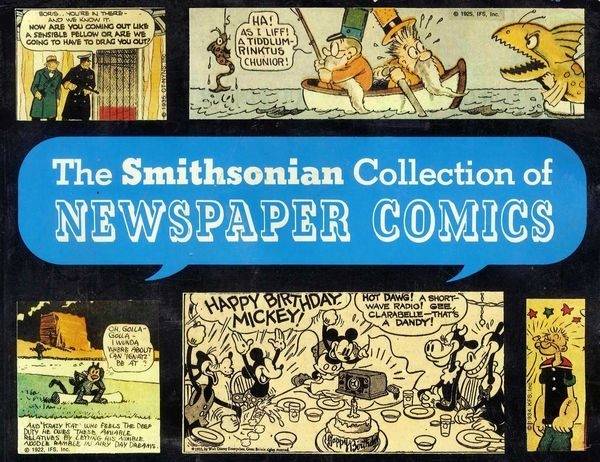

popular book reprinting select runs and examples from the great comic strip efforts in history. In 1977, with Martin Williams, Blackbeard co-authored

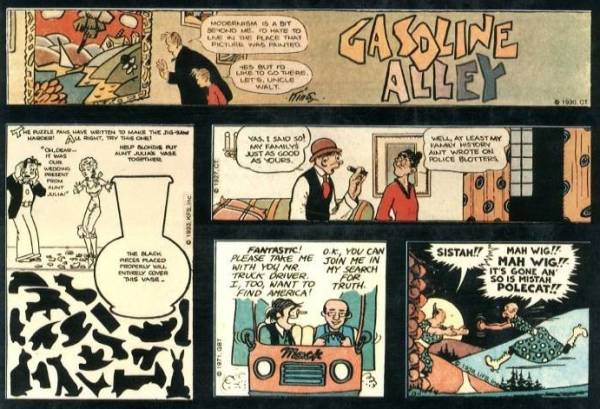

The Smithsonian Collection Of Newspaper Comics. In doing so, Blackbeard changed the direction of comics and the direction of many lives of those that choose to read them. It is one of the ten most influential and important publications in comics history. The

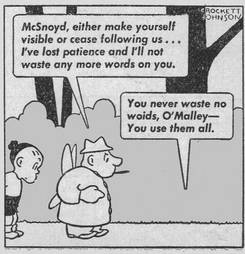

Smithsonian Collection exposed multiple generations of comics readers to dozens of comic strips that they hadn't yet seen. Remember that even for those fans like Blackbeard that lived when many of the great strips were published, readership was frequently limited to whatever newspaper the family took. Some of the best strips, including Crockett Johnson's

Barnaby, to name one whose reputation was sealed by publication in the collection, never enjoyed the massive market saturation that the average hit 1970s gag strip might have secured for itself. Also recall that while comic-strip collections weren't an absolute rarity by any measure at this point, this kind of astutely collected book did stand out, and was perfectly oriented to hit any younger cartoonist wannabe scrambling for any books and material he could find in bookstores and in libraries. This includes most of the first alternative comics generation, many of whom cite the Smithsonian book, or some comic discovered there, as a significant influence. The world of comics as conceived by many comic book fans doubled; the world of comics as conceived by comic strip fans now had a physical touchstone. One measure of the

Smithsonian Collection's influence is that you can count on one hand the number of newspaper comic strips that have come to be well-regarded in the years since that did

not have a significant entry in that book. Another is how many similar efforts basically ape its approach and format, frequently to reduced effect. It remains a titanic achievement, a book of a lifetime.

Blackbeard's contributions were certainly not limited to any single work, even one as rightfully lauded as the

Smithsonian Collection. He contributed material and efforts of scholarship to over 200 books in his lifetime. His archives and knowledge, both of which were almost always freely shared, proved foundational to three great flurries of comics reprint publishing, some of which he directly participated as editor. In 1977, the same year of the publication of the

Smithsonian Collection, the Hyperion Library of Classic American Comic Strips offered up a sweeping panoply of early comics work, some of which hadn't been seen since their initial publication six decades earlier, including such foundational strips as

Bringing Up Father or those whose cultural reputations had changed from their heyday, like

Skippy. In the 1980s, Blackbeard made possible two crucial

Krazy Kat series (one from Eclipse; one from Fantagraphics), and the massive effort from NBM collecting the crucial adventure series

Terry And The Pirates (of which there were 12 volumes) and

Wash Tubbs (18 books in all). In the 1990s, not coincidentally a fallow time for American comic book publishing on a lot of levels, Blackbeard worked with Dale Crain on the best companion book to the Smithsonian Collection, the double-volume

The Comic Strip Century, as well as to one of that decade's best stand-alone historical/reprint efforts,

Richard Outcault's Yellow Kid.

In 1997, Blackbeard sold the vast majority of the SFACA holdings to the Cartoon Library & Museum (now the Billy Ireland Cartoon Library & Museum) at Ohio State University, and began the processing of moving his holdings to that Midwestern campus in early 1998. It was a huge stamp of approbation for the yeoman's work done by museum curator Lucy Shelton Caswell in growing OSU's holdings from a few personal archives into a major cultural institution. One piece of legend that turned out to be true is that the bulk of the material made its way to Columbus in six massive trucks; another was that the collection wasn't organized in a way that a university library could immediately put the collection to use, which caused ripples throughout the reprints collection community. As an editor working with reprints at the time, I can remember one series being put on hold due in great part for lack of access to quality strips as one came to expect of those archived by Blackbeard. R.C. Harvey's obituary linked to in this post's first graph indicates that over half of the original files may still have yet to be organized despite the best efforts of any number of grant-supported workers setting themselves to the Herculean task. As OSU's reputation has only grown since taking on the bulk of the collection, there's a good chance that the holdings will continue to have an impact with everyone from researchers to publishers for decades to come. For his part, Blackbeard and his wife moved to Santa Cruz with some key, cherished collections. At the time of his death, Blackbeard had been in nursing home for an extended period of time.

Bill Blackbeard was placed on the Will Eisner Hall Of Fame nominations ballot in 2004 at the primary insistence of judge Andrew Farago of the Cartoon Art Museum, and has remained in cycled reconsideration ever since. He is up for the honor of inclusion again this year, via on-line voting that ended in that time period after the historian's passing but before it was made widely known.

Through a lifetime of acting on a child's impulse in a way that never doubted the value of its attention, by combining the roles of enthusiast and collector and historian and advocate, Bill Blackbeard changed comics from the way they're published to the way we think about them. He became one of the great figures in American comics history, a man whose life and work touched on as wide a swathe of books currently on the racks as all but two or three other individuals. He will be missed in equal measure to how he will continue to be felt.