Home > News Story and Obituary Archive

Home > News Story and Obituary Archive Obituary: Pat Boyette 1923-2000

posted December 31, 2000

Obituary: Pat Boyette 1923-2000

posted December 31, 2000

Aaron "Pat" Boyette, a strip and comic book artist most closely identified with Charlton and Warren, died Friday afternoon, January 14th, in Fort Worth, Texas, following a long struggle with pnuemonia and related bronchial problems. He was 77 years old.

Boyette was born July 27, 1923 in San Antonio, and remained in San Antonio for the majority of his life, excepting certain periods where he moved to remain close to family. As a child and later as a young adult, Boyette lived in various locations related to his father's employment, while a recent move to Fort Worth was designed to put him in closer physical proximity to a daughter. But Boyette considered himself first and foremost a San Antonian, and was proud of a Texas comics tradition that stretched from Jack McGuire (

Bullet Benton) and Roy Crane (

Wash Tubbs), to V.T. Hamlin (

Alley Oop) and Boyette's close friend Jack Kent (

King Aroo). While the self-effacing Boyette would not have placed himself in that company, or even described himself as a full-time cartoonist, friends and acquaintances agreed he had one of the more interesting personal and professional histories of anyone working in comics.

One fact distinguishing Boyette's comics career from those enjoyed by other Texas cartoonists and many of Boyette's contemporaries was its relative late start. Despite a lifelong interest in the comics form he could trace back to the primacy of newspaper comic strips in the homes of families during the Depression, Boyette enjoyed a number of careers before becoming a regularly-employed comics artist.

Boyette's first major career, and that for which he was best known in the San Antonio area, was that of broadcaster. He began in radio as a teenager, working his way from an office boy position secured with the help of a family friend into a news producer position and then disc jockey/announcer for San Antonio station WOAI. Boyette would later say that he was so overjoyed to be working in radio he would work an average of 60 or 70 hours a week. "I'll never forget the first time I walked into a radio station... The lure of that microphone, the excitement of what this really meant, just could not be denied."

His work as a news announcer allowed the young Boyette a draft deferment, and when the deferment wasn't filed for a second six-month period, the broadcaster was drafted and served in World War II. He returned to radio station KONO after the War.

Boyette soon made the switch from radio to the burgeoning television medium -- "those glowing boxes," as Boyette would later describe them. Boyette later spoke of his work in the initial days of television with great dramatic intensity, calling it a shared cultural experience that would never be repeated. His desire to switch from radio to television was often illustrated by a story in which he saw people enraptured with the new technology. And the reaction of people to his first broadcast on San Antonio TV also gave birth to a story.

"The next day I caught a bus into town. I kept noticing people were looking at me. And I thought, 'What in the world are these people looking at? Am I unzipped? What are they looking at?' Then it dawned on me: they were looking at me because they had seen me on the box. And from then on, you became, strangely enough, a celebrity of sort. You couldn't go anywhere or do anything without being recognized or catered to."

Boyette was primarily a television newscaster for 20 years, and remain involved with TV and radio in a limited capacity through the remainder of his life. It was during his first period working full-time for station WSTA that Boyette started work in comics. Meeting

Ella Cinders artist Charlie Plumm while doodling in the art department of the television station, Boyette soon worked with Plumm on a strip,

Captain Flame, for Plumm's small, regional syndicate. Despite professing great pleasure in working in comics, Boyette chose not to continue

Captain Flame when Plumm sold the strip's rights to the Smith Syndicate. One factor in giving up the strip work may have been fatigue -- Boyette drew the strip in his office between broadcasts.

In the early 1960s, another career beckoned. A self-described "bored" Boyette calculated that television's continued growth would lead to the need for more movies to fill broadcast time, both in the afternoons and late at night. As a result, Boyette became an independent, low-budget filmmaker seeking to follow in the path of an entertainment business idol, Roger Corman.

Like the Corman pictures and other regional films of the time, Boyette's films were made on the cheap, with the broadcaster and part-time cartoonist providing the script, direction, and art direction for the entire production. Boyette would then try to seek distribution for the films himself, a process he once kiddingly described as "begging." Boyette's signature, best-remembered film was the 1964 (Boyette in one interview says 1962) horror movie

Dungeons of Harrow (also known as

Dungeons of Horror, or

The Dungeon of Harrow), starring then-San Antonians Russ Harvey, Bill McNulty and Lee Morgan. Narrated by Boyette, the film tells the story of shipwrecked survivors fulling into the machinations of a doctor on a mysterious island.

Brad Beshaw, owner of Seattle's Hypno Video, says that the fact that

Dungeons of Harrow is the film of Boyette's to remain known and distributed is really "just a lot of luck." Asked to describe Boyette's signature work, Beshaw called it "a super-heinously low budget film. It was one of those Marquis de Sade movies, along the lines of a simliar film by Mickey Hargitay, where the plot seemed to be an excuse to get a lot of girls naked." Behaw added, "Because it's so cheap, it's genuinely creepy. The atmosphere... it's claustrophobic, and you can't really recognize any of the actors. I hesitate to say it has a 'snuff film aesthetic', because there's really not so much snuff films as much as there's something called the 'snuff film aesthetic'. It's simply very cheap, and very weird."

For his own part, Boyette had a modest view of his accomplishments, but expressed pleasure over the years that

Dungeons of Harrow continued to be seen, expressing a different view of the film than Beshaw. "The kids love it," he told interviewer Ken Smith in his

Comics Journal interview. In defense of the artistic merit of his movies, Boyette said in an earlier interview that

Dungeons of Harrow suffered from the casting of Harvey in the lead, and the fact that his distributor wanted 90 minutes of film forced the director to leave in at least 20 minutes of unnecessary footage. But in general, Boyette was humble about the quality of the films he made, and enjoyed the total creative control of the process. He produced another film with complete creative control,

No Man's Land. But the experience of having a scripted work,

The Weird Ones, taken out of his hands (Beshaw told the

Journal the credited director was actor Harvey, and that Boyette is listed as a co-producer), and a failure to place a science fiction film with Roger Corman despite an offer to try directing a script Corman provided, seemed to be disillusioning for Boyette. He placed one more script,

The Girls From Thunder Strip, with a fellow renegade filmmaker, David Hewitt. The loss of his filmmaking equipment in a fire was taken by Boyette as a sign his filmmaking days were over.

In the mid-1960s, Boyette was commiserating with a friend in San Antonio over those aspects of their careers each found unfulfilling when a shared artistic interest led them on a lark to pursue jobs drawing comic books. Following up on a Charlton comic book randomly selected by the friend, Boyette called the company, made sure they were looking for artists, and sent along samples. When Charlton replied to his mailing, it was to say the company was re-structuring, and they would contact him in a year. Boyette recalled putting the thought of working for Charlton out of his mind.

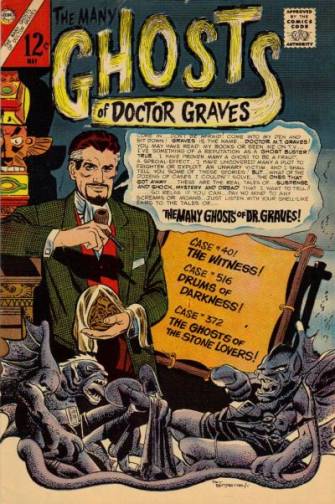

Almost a year to the day later, Charlton and Dick Giordano provided Boyette with scripts to draw, and thus began the longest professional comics relationship of his career. Boyette's first story was called "Space for Rent," and he soon established himself as an artist on several of Charlton's anthology titles. He would also eventually do work for "name" series. Giordano noted that Boyette did more work than a book called, saying of one later assignment at DC, "It was a stupid idea, and the writer didn't do very much with it. But Pat did everything he possibly could. I recently looked at that work again, because I was doing a miniseries for DC featuring the character. Looking through that material, I was even more impressed now with what Pat did. I was running around all the time, with 17 books. Only when I left was I able to look at the books with an arm's length persepctive. In the heat of battle, you don't realize what you had."

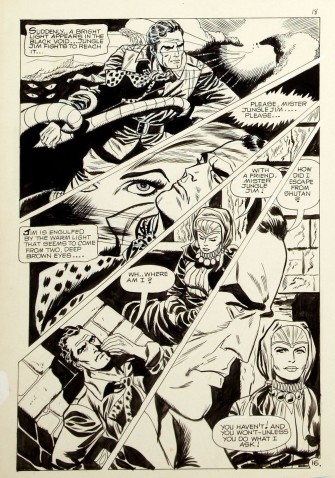

Perhaps because he started in comics so late, Boyette brought to comic book art a number of habits that seemed strange to fellow artists. One was that he didn't like to work in the customary oversized format for comics pages, getting special permission from Giordano to work at a smaller size. Says friend Tom Sutton of Boyette's desire to work smaller, "He considered work oversized a waste of paper! He had this little thing that would be drawn on copy paper, and colored. It would be all wrinkled, but he found if you put it under the scanner it would flatten it all out. The real kicker was drawing it that size is impossible. And lettering at that size is madness. But you couldn't tell!"

A phone relationship with fellow Charlton artist Rocky Mastroserio led Boyette to the other publisher with whom he's closely linked: Warren. Mastroserio hired Boyette to perform ghost work for him on a couple of assignments, and when the artist passed away, Boyette contacted Warren who encouraged him to continue on the job. Like his ongoing stint at Charlton, Boyette's stay at Warren was distinguished in many ways by its autonomy. Doing stories for

Creepy and

Eerie in a horror vein reminiscent of

Dungeons of Harrow, as well as painting covers, Boyette later said he was never asked to make changes and almost everything he sent to Warren, with the exception of a few spec covers, was used. Many believed that the Warren material was the best comics work of Boyette's career.

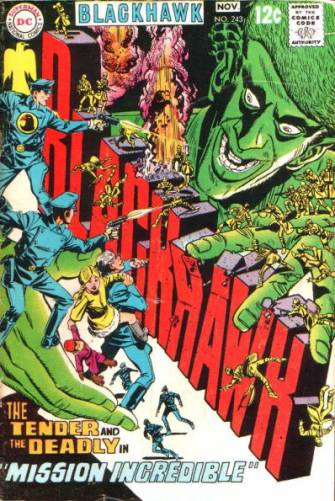

Remaining one of Charlton's workhouses, Boyette ended up working just about everywhere in comics. He was one of the Charlton artists who followed Dick Giordano to DC, although the experience of working for the major publisher, including turning around seven pages of

Blackhawk art in a single day (Giordano told the

Journal Boyette's work on the difficult assignment, originally given to Reed Crandall, was extremely well-done) helped dissuade Boyette from pursuing more work with them, preferring the reliable work relationship he enjoyed with other publishers, particularly Charlton.

Boyette's work for the remainder of his comics career was as eclectic as his general vocational path. He was one of the mainstays of the Atlas line that flourished briefly in the mid-'70s. He did some inking work for Valiant, enjoyed a healthy run doing comics featuring Hanna-Barbera characters, and did strip work for a Bruce Lee comic strip and with the long-running Phantom character, in addition to some other fill-in or short-term work with various comics publishers, such as First Comics'

Classics Illustrated re-launch. (Boyette's adaptation of

Treasure Island remains for sale through Amazon.com.)

It was during that final phase of Boyette's career that his interests became even more diverse within related arts fields. He worked with Charlton and a local Texas business to help provide a way to do better color separations for their covers. He also worked with a Texas printer investigating ways to more cheaply print comics. Boyette worked on a few TV animation storyboards (including episodes of

The Real Ghostbusters), put together a Texas pictorial history for an oil concern that pulled financing, and later wrote his own history of the Alamo.

Boyette's best-remembered works remain his Charlton stories, his painted covers for the same company, and his time doing very atmospheric stories as part of a strong Warren stable. A recent book by David Spurlock features some of the best pieces from Boyette's unique career and is a testament to a largely unknown, undervalued, artist.

Boyette's friends and co-workers recall Boyette's personality as much, if not more, as his work. Boyette was perhaps best known to many people in comics for his presence on the telephone, enjoying a wide variety of long-distance but close relationships with artists such as Tom Sutton, Alex Toth, Gray Morrow and Wally Wood. Sutton pointed out that Boyette's broadcast background made him a natural phone friend. "He had that frequency-modulated voice." According to Boyette, the phone conversations he enjoyed with fellow professionals were usually on every topic except comics, and were part of the way that cartoonists fought the inherent loneliness of the comic book artist's life.

Mark Evanier, who used Boyette as an artist on Hanna-Barbera comics he edited, also remembered the artist warmly. "Pat had a warm, friendly, radio-trained baritone voice that made you like him the minute you spoke to him on the phone. He was enormously humble about his comic book work, forever deflecting compliments, always hoping that he would some day do work that was worthy of the praise that many heaped on what he'd done. He was very fast -- and willing to work very long hours -- so he often bailed out editors in deadline crisis situation. We spent hours on the phone, talking about everything under the sun and, unlike many in comics, you could talk at length with him about something other than comics. I only got to spend time with him in person twice but I liked him on the phone and I liked him even better in the flesh."

Dick Giordano remembers an interesting man who was humble about his wealth of experiences. "The way he talked about his previous work, outside of comics, it almost sounded like it was something he did in his spare time. Recently I read something about what he actually did in radio and on television, and I was impressed." Although their professional relationship was conducted entirely over the telephone, Giordano later met the artist in Houston. "But I never really got the chance to speak to him the way I wanted to. I lost a good friend."

For a man who never considered himself a full-time comics artist, Boyette was grateful for his professional friendships and for the recognition afforded his work from fans. He is remembered as a true Texas original. "Here was a guy who had a hell of a lot of fun, and accomplished a lot of things that other people never did," said Sutton. "He was a dear person."

Pat Boyette was preceded in death by his wife of 54 years, Bette. Survivors include a daughter, Melissa.

Originally Published in The Comics Journal #221

Originally Published in The Comics Journal #221