Home > Commentary and Features

Home > Commentary and Features Fort Thunder Forever

posted December 31, 2003

Fort Thunder Forever

posted December 31, 2003

Introduction

Introduction

Arts movements require proximity and a shared outlook. Comics has long been big on the first and not so hot on the second. Since the medium's cohesion into an active artistic outlet late in the 19th Century, cartoonists have frequently huddled in the same place. Early cartoonists were bound by their common identity as newspapermen, and many spent at least some time in a bullpen working elbow to elbow with their peers. The early comic-book industry was dominated by New York City, and if you squint, the stories of studios being thrown together and artists working on each others' pages sound like the beginnings of the kind of back and forth that galvanizes certain approaches to the form. But commercial concerns didn't merely override more ambitious concerns; they steamrolled them. More importantly, these were not the kind of commercial concerns that left much if any room for artistic expression.

After a few decades, as industry relationships deepened and mail service improved, more comic strip cartoonists and comic-book artists began to drift back into their natural state of self-isolated productivity. Many of the strip artists began slinking down to Florida after World War II while a big cross-section of working comic-book people would eventually move West. Later, artists and writers entering the industry could avoid moving to New York City altogether. The underground-comix cartoonists of the 1960s shared geographical close quarters (most were in the Bay Area, or spent some time there) and a resistance to corporate expressions of and limitations to art. They remain the closest thing comics has to a recognizable true movement. The idea that sharing between peers might be valuable has been echoed in most recognizable groups of cartoonists that have popped up ever since - from the bearded, ball-capped second generation at Marvel and New DC to the Seattle Story Ark crowd of the early to mid-1990s to what I'm assured are close-knit smatterings of burgeoning talents in St. Louis, New York City and Los Angeles today.

Fort Thunder was different. The Providence, RI group has achieved importance not just for the sum total of its considerable artists but for its collective impact and its value as a symbol of unfettered artistic expression. The key to understanding Fort Thunder is that it was not just a group of cartoonists who lived near each other, obsessed about comics and socialized. It was a group of artists, many of whom pursued comics among other kinds of media, who lived together and shared the same workspace. As an outgrowth of the Rhode Island School of Design [RISD] where nearly all of them attended (some even graduating), Fort Thunder provided a common setting for creation that imposed almost no economic imperative to conform to commercial standards or to change in an attempt to catch the next big wave. They were young, rents were cheap, and incidental money could be had by dipping into other more commercial areas of artistic enterprise such as silk-screening rock posters. Fort Thunder was also fairly isolated, both in terms of influences that breached its walls and how that work was released to the outside world. This allowed its artists to produce a significant body of work that most people have yet to see. It also fueled the group's lasting mystique. The urge - even seven years after discovering the group - is not to dig too deeply, so as not to uncover the grim and probably unromantic particulars.

In The Fort

Fort Thunder was a key player in several arts scenes. In terms of its place in comics, Fort Thunder describes the group of artists who made mini-comics and cartoon art while living in Providence's Fort Thunder work and living space in the mid to late 1990s. Although several of the artists working there dabbled in comics, as did many likeminded artists not in the space, there are six artists on whom which we'll concentrate, who make up the core group of talents to emerge from the Fort in its initial flowering:

Mat Brinkman was born in Texas. He attended a special high school for the arts before entering RISD, where he studied printmaking and sculpture. His comics contain monsters and other fantasy-tinged creatures exploring elaborately constructed, roughly textured environments.

Raised near Philadelphia, Brian Chippendale was Brinkman's roommate during their freshman year at RISD. His comics, often drawn in pre-printed journals, feature sequences told in panel progressions that favor a snake-like pattern rather than conventional left-to-right storytelling.

Jim Drain met Brinkman in classes at RISD and moved into Fort Thunder with a second wave of artists and cartoonists. Acquaintances call Drain the most socially assured and charismatic member of the group. His comics feature thin lines, awkward figures and sparse backgrounds.

Leif Goldberg was raised in rural areas in the Mid-Atlantic and Northeastern United States. His comics feature vibrant color and musings on ecological themes.

Brian Ralph was born and raised in New Jersey. His comics are metaphorical fantasies set against lush backgrounds and drawn with an animation-ready line. He has thus far enjoyed the most traditional comics-publishing success of the group, with two books released, comics-industry-award nominations and gigs with comics-friendly magazines.

Paul Lyons became friends with Ralph early on during their time at RISD, knew Brinkman through skateboarding and moved into Fort Thunder with Ralph and Drain when the space expanded to its full size. Many of his comics are drawn in a traditional illustration style.

Before being appropriated by fans of comics, music, performance and printmaking, Fort Thunder was the name of a place: a living and performance space located in the Olneyville neighborhood of Providence. It began in 1995, when Brinkman and Chippendale sought an industrial location where Brinkman could book shows. That it would also be a living space for those involved was never in question: "We couldn't afford both," says Brinkman. It would also house the studios for any other arts the residents wished to pursue. Extra studio space would cost more money than many of them could afford, and space provided by RISD was available only as long as the students stayed enrolled, never a guarantee. Many of the artists living there also needed a way to make art that would in some way pay for their modest portion of the rent. The original residents were Brinkman, Chippendale, Rob Coggeshal and Freddy Jones.

The name "Fort Thunder" was selected by the quartet almost immediately upon moving in, as the space needed a name in order to advertise its music shows. (Brinkman says its first show was held within a month after opening.) The name is related to the fact that the space, on the outer edge of a sparsely populated neighborhood near downtown, allowed the music to be played as loudly as they wanted. Brinkman also liked the idea of a Fort where "you're there to defend yourself from the quietness of American bullshit." Another explanation given in a local newspaper article years later is that the words provided a play on nearby "Howell Lumber." The name proved appropriate, acting as the kind of buffer intended, but also encouraging the same type of isolation and absolution from responsibility that traditionally leads kids to build treehouses or dirt forts. Fort Thunder was a place where the aspects of adult life unnecessary for sustained artistic output could be kept from walking through the door.

The Fort flourished. Several months later (testimony differs whether the year was 1995 or 1996), the group of artists living there - primarily Brinkman with Chippendale's assistance - had been successful enough scheduling shows that the Fort's role as an important Providence-area performance space took on a life of its own. When their landlord threatened to rent the remaining floor space to an outside tenant, those living there took exception and invited like-minded artists to move in so they could subsume the rest of the area. This cartoonist-heavy group was Andy Estep, Brian Ralph, Jim Drain and Paul Lyons. Upon settling in, the new members found that the original residents had been working on their individual living areas as if each was an arts project just as important as any of the traditional work being done in the studio areas and performance space. The new members worked hard to catch up, the old members took advantage of the expansion and eventually the once entirely-empty space would be transformed into an indoor city of sleep areas, living spaces, and working areas - more science-fiction "terra forming," the creation of an alien environment, than legitimate interior decoration.

The Fort took up the entire second floor of a building in Eagle Square. Visitors who entered the building did so through a door over which remained a large painted arrow, the detritus of some long-forgotten painted advertisement. Several visitors recall a massive pile of bicycles and bicycle parts in the front room. The performance space just beyond that was most like the original warehouse. It has been described as having 25- to 30-foot ceilings and a massive length of floor (one visitor guessed "half an acre"). Wooden columns intermittently placed stretched from floor to a shadowy ceiling. The area was impressively big. Bands could set up in the middle of the room if they wanted to, rather than stuffed up against a wall as was the norm in privately owned performance rooms. Other parts of the room might even accrue their own sets of debris. One show attendee described a seating arrangement in one part of the space of 50 to 60 mattresses, strewn about the base of one of the columns, formed into a pile ten feet tall and 40 feet wide. Some of the uniquely constructed bikes lying about might be ridden in this area. The open space sweeps into the kitchen, which connected to the living spaces through one of the more memorable design flourishes; a refrigerator door, or as it was described by one visitor, "a fucking refrigerator door."

Former Fantagraphics art director and

Journal contributor Evan Sult toured the space in 1997 while on tour with his band, and described the living space in awed tones:

"So we start poking into people's rooms. Everything was immediately critically bizarre. My sense was that there were no real ceilings on the rooms; because the ceilings were so high, they just built the walls ten feet high or so and quit. Or didn't quit: that was when they attacked the walls, covering them with all kinds of crazy shit. There were bike parts everywhere, in amazing colors. I wouldn't swear to it, but I think I saw a pair of square tires, with spokes and everything. There were screenprints, posters, cast-offs from projects. I don't seem to recall a horrible stench or piles of laundry or anything else that I would have associated with a bunch of mentally disturbed people living together. There were piles of stuff, and it was a lot like a squat, but it was like a dream squat: all the records were good, everyone here was actively productive, all the posters were screenprinted and all the drawings were intriguing. The books on the shelves were comics and sci-fi and literature, a really bizarre mishmash that I associate with vegans and anarchists and juniors at university. And zines. And handmade clothes. And squeegees and paintbrushes and bottles of ink and carving utensils and glue and chicken wire and stacks of parent sheets and stapleguns and all of the stuff you could imagine needing to make something awesome. And after all of this overwhelming information, like 10 rooms or something, I finally noticed that the walls in the halls were covered with comics panels, by that guy who does obsessive drawings of Warlock from the New Mutants. The panels were probably no bigger than an inch square. There were untold thousands of them, literally, and they completely covered the wall, from the floor to however high the wall went. And then, on top of that, there were these Army soldiers glued perpendicular to the wall, in battle with one another. Seriously, there was enough room that whoever had glued that shit up there had illustrated whole battalions, one outflanking or ambushing another. They were just crawling violently all over the wall. Then we could hear Popesmashers tuning up in the other room, so we staggered out toward the music. All I can remember about leaving that space is that we didn't go through the fridge on our way out. Later, blissed out and with a serious buzz, I watched clumps of people hanging out or passing by the kitchen. I didn't see a single one of them use that door. It's like it really was a secret entrance.

Longtime

Journal contributor Robert Boyd, who made a trip to the Fort Thunder space with publisher Tom Devlin, noted that the ceiling that was obscured from sight on some evenings was "covered in hanging things - bits of garbage and junk. I specifically recall an old tricycle hanging down. There was no sense of this being a mobile, nor was there a design that I could see." He also noticed that none of the rooms (many of which were created from plywood) escaped a sense of artistic contribution: "The bathroom was the most room-like room, but again it was covered - every inch - in stickers, glued items, drawings and painting. It was clear that the artists had dialogues with one another through their decorations - that one graffito would be answered with a piece of collage." Boyd notes that the term that best describes the need of the artists to fill every inch of their space has a name that evokes its artistic qualities, as in this quote from E.H. Gombrich's

The Sense of Order: "The urge which drives the decorator to go on filling any resultant void is generally described as horror vacui … Maybe the term amor infiniti, the love of the infinite would be a more fitting description."

The unique qualities of the space in terms of design and decoration remains one of Fort Thunder's enduring legacies in art. The Fort's first comprehensive national profile was in Lois Maffeo's article for the design magazine

Nest's 13th issue (summer 2001). It included a number of photos by Hisham Bharoocha of the different living areas as well as discussion with the various artists who most directly influenced the more extreme flourishes. (A map of the Fort, drawn completely not to scale and with a large curve to the outside walls where none existed, also ran in that piece. It looks like a cross between Marie Severin's depiction of the 1970s Marvel bullpen and a cancer cell.) The visual cacophony had a definite impact on those visiting - Sult proclaims that his sense of design was "destroyed" by his visit. It also clearly influenced the kind of work being done there - Ralph has admitted a lingering fascination with living spaces in all of his work, and the Fort as a direct spur to the caverns depicted in

Cave~In. Brinkman's work is also very much about place, while Chippendale has since extolled the virtue of building things in real life as a balance to the imagination fueled creative act facilitated by comics. The stories of Fort Thunder haunt younger fans that did not get to visit - cartoonist Sammy Harkham calls missing out on seeing the place "one of the most disappointing things in my life."

Members estimate that about two-dozen people lived in the space over the course of its existence. The maximum number of permanent residents at any one time was approximately 13, a number hard to gauge because of the ability of people to live temporarily in the tiniest amount of real estate afforded by the Fort. There were female residents at various times, whose unique contribution, according to Brinkman, was keeping everyone from breaking as much stuff as they usually did. Comics continued to be made throughout, hand-assembled with material created in the printmaking area. But the house may have been best known for featuring a staggering variety of artistic activities of which comics was only one, from efforts as obscure as role-playing to more standard activities such as the well-received rock shows.

Fort Thunder has as impressive a legacy as a live-music venue as it does a living space or genesis point for comic books, if not more of one. The performing space could hold 150 people comfortably, while 50 to 100 more people than that was pretty common. Access to a regular venue and the booking philosophy of the residents galvanized a local scene and a series of sort-of house bands that included the incredibly popular Lightning Bolt (Chippendale and Brian Gibson) and such groups and fractions of groups as Landed, Forcefield, Pleasurehorse, Mindflayer (Chippendale and Brinkman), Marumari, 25 Suaves and The Olneyville Sound System. Local bands used the Fort as an important regular venue and launching point, one of only a few at the time in an area saturated with forward-thinking young people and artists. Bands from far outside of Providence stopped by on tour, or tried to. It became an important destination point for a growing web of similarly conceived artistic communities across the United States, and for artists interested in finding unique places to play while on tour.

What Fort Thunder could offer bands is a place to play and hang out that did not feature the commercial atmosphere of a bar - no demands were placed on the musicians, and Fort Thunder residents were happy to share the rough amenities of what they called home. What the Fort offered fans of music and local scenesters was an intimate show atmosphere, a place to hear bands that allowed for noise and exploration instead of commercial tune-making if that was their desire, and a series of energetic shows that slipped over into other media. Frequent attendee Ben McOsker of Load Records reminisced in an interview: "My favorite events were the wrestling with speed metal DJ's, featuring a battle royal at the end with a large multi-person creature." The costumed rock performance became a well-known staple of Fort Thunder, and the act of changing the physical appearance of things became another vital avenue those at the Fort explored.

Not only did members of the group slip between areas of artistic exploration, so did the groups. The band/arts collective Forcefield grew out of what Drain calls a "drawing jam," eventually swelling from two (Peterson and Brinkman) to four members (Drain, Brinkman, Goldberg and Ara Peterson) and taking on performance/music aspects. The group wore elaborate costumes; suits knitted by Drain, which gave their shows an eerie, unearthly feel and their press material claimed indicated they "dressed to impress." A 2001 show entitled "Forcefield" at Parlour Projects in Brooklyn led to interest from a representative of the Whitney, and brought about a follow-up visit to the Fort. This contact would result in one of the Fort's most important moves into the American arts mainstream; an invitation to produce a work of art for the 2002 Whitney Biennial. The installation "Third Annual Roggabogga" featured elaborately constructed costumes, statues and audio experienced in dim light. Described by one critic as a "psychedelic fun house" and another as "inane," it became one of the galvanizing, signature pieces of the show.

The legitimacy that comes with such an opportunity may have arrived too late; it probably wouldn't have mattered. Starting as early as 1997 and intensifying in 1999, rumors began to circulate that the building that housed Fort Thunder was about to be sacrificed to the general growth and development of the Providence area. In actuality, the city had been looking to gentrify its mill properties since the late 1980s. Suddenly the Fort's fate was in the hands of a story 150-plus years old in the making. Mill building development had long been a prickly subject in the town and throughout the Northeast. Mill operations, particularly those harnessing steam power, had put the city on the world map in the 19th century; by 1900, Providence was a regional manufacturing powerhouse. But its industries' decline the first two decades of the 20th century, fears of organized labor and the deleterious effects of the Great Depression moved many of the businesses into what was then the United States' own third-world country; the American South. Reagan-era economic policies accelerated the fade of what remained and by 2000, Providence factory employment had declined by more than half from its modest 1960s levels. What, then, to do with the buildings? Movements to preserve the structures as part of the heritage of American history had been slow in developing; many of the ideas behind these efforts were ventured in articles on industrial architecture in the 1960s, with some community efforts sprouting up in the late 1970s. But while many buildings in Providence had been surveyed, few had been protected.

In a twist on most millennial concerns in the air at the time, Brinkman says that the possibility that the world might end suited those living there at the time, because they would assume total control over the Fort. By 1999, these rumors began to seem more credible, and the eventual sale of the property to a group called Feldco for a retail space called the Eagle Square Project was announced. Unlike other similar urban reclamation projects, Eagle Square was to demolish several mill buildings in favor of new construction. Taking the place of the building housing Fort Thunder (and a thriving flea market) was a single-story structure housing a store from the upscale grocery store chain Shaw's. Fort Thunder became a local cause, a sterling example of the kind of vital arts community that would be lost to the New Providence to make for a few pieces of high-rent property. As writer Ian Donnis adroitly pointed out in his massive article "Eagle Square: The Rhetoric and Reality of Nurturing the Arts" (

Providence Phoenix, December 2000), such efforts might be counterintuitive: "An artist, designer or Internet start-up is never going to move here because of a supermarket, but they might just be fascinated by the reuse of an old industrial space." The anti-development advocates were quick to grasp the Fort's identity as a unique creature within Providence's culture, part of what makes that city unique, as well as a sign that artists in general may start moving in search of cheaper rents in nearby Central Falls and Pawtucket.

Yet despite several artist-led protests throughout the process, some politicized art from the cartoonists involved (Chippendale's work in particular among the cartoonists) and general acts of displeasure (the Fort's penchant for making noise was put to good use outside its windows), the project steamrolled on, with a few late concessions involving the use of certain mill buildings that hadn't immediately been demolished. As much as it may have given community forces ammunition for future tussles, this time out Fort Thunder's space was a casualty. On Jan. 31, 2002, the space hosted its last show. Eventually, the building that housed the Fort was locked to keep its longtime residents out. Only by gaining special permission were many allowed back in to retrieve as much of their personal property as possible. In May 2002, the wreckers began to move in. Although relative few artists in the Fort's wider circle would move out of the Providence area entirely - and in some ways, the artistic community had been galvanized by the fight and had won a potentially more significant place for themselves in the future development of Providence - it was definitely the end of an era.

Outside the Fort

One of the reasons for a continuing interest in Fort Thunder's comics is the group's relative mystery. They have released work slowly, and almost all of what the public has seen has been compelling, if not bordering on the inscrutable. More work has been released to a relatively small circle of comics insiders and fellow cartoonists than to the general public, keeping the group's reputation secure among what passes for opinion-makers in comics and creating a unavoidably hip vibe based on scarcity. This rolling discovery could not have been executed more effectively had it been planned, but it's largely an unavoidable consequence of how the artists have worked. The vast majority of the comics done by Fort artists are disposable mini-comics with small print runs and a relatively difficult screenprinting processes utilized for the covers. In addition, the extremely sympathetic and supportive publishing partner of many of the artists, Highwater Books, has struggled in recent years to keep a full release schedule.

An awareness of what each artist was doing would develop glacially, but there always seemed to be some sort of receptive audience. Only the extremely well-connected knew of the cartoonists' earliest efforts. Cartoonist and RISD alum Jason Lutes remembers reading a very early Brinkman effort and seeing some of the qualities that the Fort Thunder group would capitalize on a few years later. But at the time, he saw what Brinkman was doing in the context of a RISD comics scene. "My first encounter with their work was through my friend Howie Rigberg, a musician and erstwhile cartoonist who went to Brown when some of the Fort Thunder guys were at RISD, and participated in the famous parade/happening that involved some Fort Thunder guys and got the College Hill train tunnel shut down. He and I were working at Fantagraphics at the same time (1992), and he showed me a mini-comic by Mat Brinkman called

Kap Trap. It reminded me a little of the work or a RISD mini-comic contemporary of mine named Joe Fullerton, in its gloomy and atmospheric use of a forest as a setting, but where Joe's work felt rooted in the cruel mechanics of the natural world, Brinkman's evoked something basic, indescribable and compelling. 'Dreamlike' would be too simplistic a description. 'Sub-lingual'? 'Ur-human'?"

Brinkman and Ralph had developed local reputations for their work by giving them to friends and taking advantage of local distribution drop points. The positive feedback Ralph received from his fellow students, around Providence and through the mail-order-zine world played a big role in keeping his attention on comics. One of the cartoonists with whom Ralph had traded work was the then Chicago-based Jessica Abel (

Artbabe). When she and Windy-City-suburb cartoonist Joe Chiappetta (

Silly Daddy) made their way to Cambridge for a signing, Abel suggested to organizer Tom Devlin that Ralph be included. Ralph made the trip, one of the first times he had set foot in a well-organized comic book shop. Among others, Ralph met his future publisher Devlin and Robert Boyd, who, in addition to being the founder of the

Journal's "Minimalism" column was a well-connected, long-time editor in the alternative-comics industry then working at Kitchen Sink Press.

Ralph continued to send his work out, and the fifth issue of

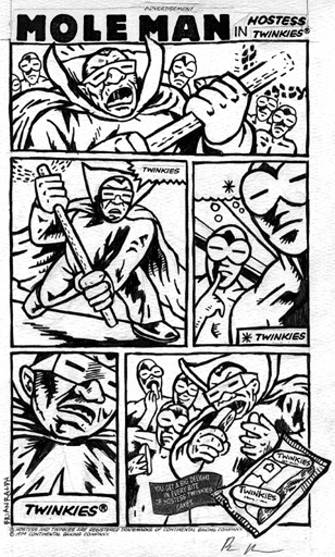

Fireball was reviewed in the September 1996 issue of this magazine. This was another audience reached for the first time, including small press cartoonists such as John Hankiewicz working in parts of the country far removed from the buzz that Fort Thunder was garnering as a performance space. That following summer, the bulk of the alternative-comics world became acquainted with those Fort Thunder artists who published in Tom Devlin's

Coober Skeber #2. This was the "Marvel Benefit Issue," which featured alternative cartoonists doing their takes on Marvel superheroes. This was exactly the context in which incredibly idiosyncratic approaches to the form would stand out, and Chippendale's application of his unique sensibilities to the adventures of Daredevil wowed his fellow cartoonists. K. Thor Jensen: "I was living in a shared house in Seattle with Jon Lewis at the time and he did a story for that book. His comp copies arrived and I remember being especially blown away by Brian Chippendale's

Daredevil story that read in his 'worm' style, where you read the tiers of panels in alternating directions. His line work was so unlike anyone else working in comics then, except Gary Panter …" At this point, the Fort mini-comics were continuing to receive attention as well, particularly with the growing alternative and small-press convention scene giving the decidedly non-Diamond-friendly work a chance to be sold face to face. Despite such limited exposure, Brinkman, Chippendale and Ralph nonetheless were individually profiled in this magazine's 1998 Young Cartoonists issue (#205).

The next step in comics terms was to distribute some of the Fort artists through trade book publishing, and these efforts were solidly conceived and well-received. Ralph's initial publishing success with Highwater Books (

Cave~In sold briskly and was nominated in all three major industry awards; the Harvey, Eisner and Ignatz) and through a Xeric grant provided the Fort with an amenable and crowd-pleasing point man in the alternative-comics field, a cartoonist whose approach was relatively easy to understand while remaining engaged in the formal challenges and primal approaches to narrative in which the Fort members specialized. It also kept artists like Brinkman, Goldberg and Chippendale in a reserve of sorts, their books almost a threat hanging over the audience's heads. It's not a criticism of Ralph's skill that his books carried with them the veiled promise of even more fantastically odd treasures to come, the implication "Wait until you see what's next." More than any group of artists in comics history, Fort Thunder has benefited from prolonged anticipation.

Today, there seems to be any number of frequent Fort Thunder sightings, to the point they almost seem common. The newspaper tabloid

Paper Rodeo - featuring consistent work from Brinkman and Chippendale, less frequent work from other known cartoonists and the appearance of new yet like-minded artists - continues to publish on an irregular but dependable basis. It is the closest thing to the Fort Thunder anthology comic dreamed of by rabid fans since the mid-'90s. In some ways, the audience has begun to catch up with the work or at least seems more prepared to deal with it. Ralph continues to make inroads into mainstream publications with work in

Giant Robot and various Nickelodeon efforts. Brinkman's mighty

Teratoid Heights collection made it to print in 2003 as part of a flurry of activity from Highwater Books, and is as pure an expression of Fort Thunder's approach to comics as readers are likely to ever see. None of these efforts have been greeted as particularly odd or overly challenging. Through anthology appearances - both

Non and

Kramers Ergot feature Fort Thunder content and a strong overall presence - the continued appeal of the mini-comics, and the growing influence of the Fort cartoonists among their fellow artists, the generally odd and idiosyncratic thrust of those comics has become much more familiar. The average alternative-comics reader may not be able to tell Jim Drain from Leif Goldberg, but even the most inscrutable Fort Thunder mini can now be seen within a context nearly ten years in the making.

Under the Fort

The comics works produced out of Fort Thunder are less about a group effort than different artists sharing the same creative ferment. There are very few examples of collaborative work in terms of comics or art, and none of it is particularly distinctive. As Ralph puts it in this issue's interview, there was very little back and forth about the comics each member was creating, let alone any running commentary on theory or comics in general. But they all watched one another, and many seemed very aware when someone else in the group had done good work or made major strides in terms of artistic development. The six major cartoonists to come out of the Fort are very different artists, and their legacy will be measured in great part by how each continues to develop their talent. In terms of work produced, this is still a story very much near the beginning.

Yet despite the uncontested originality of the six cartoonists featured here, there are elements that link many of their works. Building a framework to understand how they relate to one another proves easy. It's probably most revealing to put Brinkman at the group's center when finding common areas of interest. Brinkman is the most precocious, and seems the most naturally talented and facile member when it comes to moving between various modes of expression. In terms of comics, his work reads as the prime progenitor of most of the basic ideas around which the Fort Thunder comics would revolve. In addition to being the first in the group to tackle certain kinds of comics effectively, Brinkman is a considerable artist. Says artist Ted Stearn, "I like Mat Brinkman's comics the best. They are rich and gorgeous to look at. It is sometimes hard to read and follow the images, but the visual beauty of them makes up for that."

Chippendale has provided the purest expression of many of the ideas that Brinkman works with. "I'm always looking for extreme comic-book reading experiences," says James Kochalka, "and Brian Chippendale's comics offer the most extreme comic-book experience on the planet. Too extreme for most people, probably." Drain provides a unique spin on those same core ideas, and is the most likely to surprise by pursuing new areas of artistic exploration or dropping entire elements of typical Fort Thunder stories for effect. Goldberg has taken some of the ideas of seemingly lesser importance to Drain, Chippendale and Brinkman, like the use of multiple colors and severe masking, and gone furthest in exploring them on the page. His works may be the most idiosyncratic of the willfully diverse group.

Ralph's line and quality of drawing is very different from the rest of the artists in the Fort; his work is naturally appealing and vibrant in a very slick, professional way. "I think Brian's work is spot on," cartoonist Peter Kuper told the

Journal. "It's engaging and clear. He understands visual language and symbols and applies them in an exact way that makes it a joy and interesting journey for the reader. He doesn't let fancy page design get in the way of his storytelling, which makes his work all the more accessible." The way that Ralph has come to apply what Kuper calls visual language and symbols, since refined, was deeply and consciously influenced by a clear understanding of what the other Fort Thunder artists were accomplishing. Like Ralph, much of Lyons' work is clearly divergent from that of the other five, and he is the artist who could most easily "pass" as a cartoonist working entirely outside the influence of the others. But on more than a passing glance, it's clear that Lyons has developed many of the shared ideas in his own way, primarily how they might be interpreted through more traditional modes of art and writing. He is also a dedicated printmaker. Although each artist creates work idiosyncratic in nature, some of the members are more explicitly aware of the common threads; Ralph talks about his own work in terms of how like a Fort Thunder comic it is, and expresses slight regret that some readers may be devouring his work really wishing to get to Brinkman's.

As a group, one method to start an investigation into the Fort Thunder material is to note something they're not; cartoonists that rely on representational art in their comics. Hopefully, most of you reading find the notion that art be held to a very specific standard a rudimentary idea, but this may be a bugaboo for many more

Journal readers than artists might be comfortable hearing. As recently as the Gary Panter issue (#250), some comics fans expressed puzzlement over why anyone would see value in an artist who scribbled or drew poorly. One easy way to break through years of accrued belief that art must look exactly like the reality it chooses to depict - or an idealized version of same - is to see the iconography of a comic strip and the lines that create them as opportunities for expression rather than a call for literalism or romance. Each of the Fort Thunder artists is a skilled craftsman, something obvious from the animation-ready line of Ralph and the evocative feathered-line depictions of urban settings by Lyons. It should be enormously clear upon any lengthy consideration of the other four as well, both comics and stand-alone art. Taking a second look at stories from Chippendale, Goldberg or Drain reveals that each pays great attention to design and figure drawing. All six cartoonists draw their comics for intended effect rather than a capitulation to lack of ability.

Complicating matters, most of the cartoonists at Fort Thunder seem to see value in naive forms of expressions, such as the stiff ways in which a child might draw, the burning off of ostentation in their figure drawing, and weird leaps of logic between panels. The key is that visual interest must rule over all other factors, particularly ones of expediency or commercial concerns. Rather than devaluing art, the Fort Thunder comics are linked by their grasp of the status art has in and of itself within the comics form. Encountering their art for the average comic-book reader, particularly one with no experience reading Gary Panter or who has simply embraced the technical assuredness of Clowes and Ware, is therefore like encountering a foreign object - strange homemade alcohol, or a singing voice that breathes funny and values character and phrasing over smooth delivery. Cartoonist Sammy Harkham describes his first encounter with a Fort Thunder book, Brinkman's

Bolol Belittle: "I had no idea what to make of it. It was tiny, and precious, and had thick rough green ink on it. And beyond that, the comics inside were great. The thing was it didn't 'feel' like comics. The only thing I can relate it to was when I was six years old and found a copy of

Zap #1 in my older brother's room and looked at it and thinking 'This is not comics. It looks like comics, it is comics, but comics really aren't like this.' It felt new, in the best sense of the word." These cartoonists are undoubtedly skilled craftsmen, and if your eyes don't register what they do as powerful and effective art, try and remember the dearth of context for what most of them are trying to do. Or take another artist's word for it.

Another thread connecting many of the Fort Thunder comics is a fascination with movement, particularly silent movement. The Brinkman comic

Flap Stack, for all intents and purposes the ground zero of Fort Thunder as a comics movement, compels the reader to follow a group of shapes as they move around a unique landscape before becoming involved in a natural occurrence that changes the status quo. Elements of that story can be found in most of the comics Brinkman did in the remainder of his first prolific phrase, the stories since collected in

Teratoid Heights. Ralph's little caveman moving around the changing underground world makes up the majority of his

Cave~In. Although Ralph seems to believe that this was a subconscious decision in his part to follow more traditional Fort Thunder modes of exploration, from the looks of a skater story in

Fireball #4, movement was a recurring theme in Ralph's early work as well. Lyons gets a great deal out of following his characters through basic motions in

You Have Been Wrong About Everything (looking up, standing up, going forward) while Goldberg and Drain often feature some sort of basic action as a key plot point; a fence overcome, a hill conquered.

The Fort's king of mostly-silent movement exploration is Chippendale, whose comics follow single figures moving in an indiscriminate environment. Chippendale breaks the page into multiple tiny windows and then dictates different patterns with which they should be read back and forth. In one memorable comic, Chippendale even suggests the reader might be able to find more interesting patterns on his or her own. These are his famous serpentine comics, Chippendale's willingness to forego panel structure has done much to cement the Fort Thunder gang's reputation as one of formal invention, game-playing as comics art. But most of their comics, Chippendale's included, are fairly straightforward in terms of narrative, and many feature fundamental uses of the form; shading and line thickness to show space, and exaggeration to evoke empathy for a character's circumstance. Chippendale's experimentation isn't really wild, cutting-edge play; it's a device by which the reader is forced to latch onto the artist's pacing and pay particularly close attention to changes in motion and movement with everything they've got or be dashed on the rocks of incomprehension. It's the ultimate close-up in a medium that has long been characterized by wandering eyes drifting across the page, or readers who barely soak in the art with a backward glance while the focus is on the words. Chippendale's approach isn't a rejection of formal comics properties but a recalibration that ultimately favors panel progression.

All of the Fort Thunder cartoonists seem to similarly focus on movement and story as a function of individual and place. In doing so, many of their comics are reminiscent of video games, particularly the early generation adventure games, with their focus on a single protagonist and areas to explore - many of which had nothing in them. Cartoonist Souther Salazar notes that the Fort cartoonists with whom he's acquainted have named their pets after characters in games, a sign of their ubiquity and appeal. The emergence of every new medium forces existing ones to retreat to their fundamental strengths and, eventually, embrace new ideas based on their mutual confluence. When the visuals from a Fort Thunder comic burn their way into your mind so that you see them with your eyes closed, the intensity of sensation that cartoonist Jason Little describes in

Cave~In as "it is almost as though the temperature of the room changes when the colors change," the closest experience is the video-game player who has just ended an hours-long session. Among its many distinctions based on the art itself, Fort Thunder may by virtue of age and interest house the first important comic-book artists of a world now saturated with computer-based entertainment.

Many of the most popular videogames feature a specific kind of fantasy, quests derived from stories where characters are dropped into an otherworldly environment that must be explored - the experience of the character mirrors that of the player. A lot of the work produced by Fort cartoonists seems comfortable with this specific sub-category of the fantastic, already a great distance away from the scrubbed Tolkien-style books or Hal Foster-driven depictions that one normally thinks of when speaking about fantasy comics. In keeping with their appreciation of the elementary characteristics of the comics form when it comes to movement and environment, what the Fort Thunder artists produce can be said to be more primal fantasy, work that is based in recognizable, shared, base experiences rather than derived from a specific and meticulously developed context. A lot of Goldberg's environmentally focused works have fantastic allegories at their core, and feature the transposition of animal and human kingdoms. Drain has built a cartoon iconography out of figures reminiscent of 1970s science fiction and Jack Kirby's cosmic sagas. Ralph's books are light and familiar fantasy, with mostly limited technology taking the place of modern convenience and creatures standing in for some of some of the human actors. In his comics, like a rudimentary video game, one's skills are applied to thwart various and foreboding physical obstacles built out of dream-like encounters with monstrous shapes and close escapes from atmospheric destinations.

The early works by Chippendale and Brinkman also seem otherworldly, and about the creation of place as much as marking the progress of any character. Brinkman's most recent designs and current

Multi-Force serial in

Paper Rodeo are clearly influenced by more elaborate fantasies, such as the homemade stories concocted by fantasy role-players. It is all hierarchies, fortresses and physically imposing creatures that represent constant danger. Brinkman and Ralph's stories are often very funny and ribald in a way traditional comics fantasies are not, and they are much more imaginative than the labored narratives of someone holding a quill in one hand and a Joseph Campbell book in another. Chris Lanier points to the language being used in many of the stories as a key to understanding how they may work on multiple levels. By making their creatures speak like the people who might play role-playing games and video games, the cartoonists provide "an effective inversion of the usual function of these gaming environments (where you project your mundane self into a kind of 'super-self'). It also implies that changing our world into a mythological world won't change us." For Lanier, the Fort Thunder fantasies become interesting when we look at a future that may involve spending more in more times in manufactured worlds. The comics approach "genuine 'science fiction' - the prediction that the future of society will be populated by stoners in the bodies of gods and monsters."

In addition to simply exploring an environment, many of the books created by these six cartoonists are about transgression. Here Ralph becomes group cynic, as his characters usually suffer most quickly for stepping outside the line of acceptable behavior. Brinkman builds entire stories around misbehavior, and an aberrant choice or two. His protagonists are punished but usually not completely disabled, and often their disobedience is necessary to change the status quo. Chippendale's comics burn with the energy of a five-year-old running around the yard with his pants off. The reader imagines that an authority figure might have something to say to his protagonists if only he could slow them down. Chippendale includes furtive sex as an activity more than any of the other artists, and it's in the general scenes of interaction that one gets a feeling of someone acting out. The protagonists in some of Lyons' most interesting works seem to have something afflicted upon them, with little hope for escape, figures enduring a just reaction to their own bad faith. For his part, many of Goldberg's stories seem to revolve around the consequences of defying the natural order. In many of Drain's comics, a teenager's rebellious nature mixes with the disadvantaged twentysomething's feelings of futility. All of these worlds seem somehow constrictive and unfair, and it's always obvious what rules were broken to put a character in that situation. The Fort Thunder comics remind us how thematically rigid a comic-book reader's fantasy life has always been. Most are acts of imagination anchored by an adult's concern for balance and equanimity rather than a child's desperation for wishes fulfilled.

All of the Fort Thunder cartoonists also bring an appreciation of silk-screening and printmaking to their comics. Through those processes, they have raised awareness of comics as physical objects. Because of their extreme isolation from the business of comics, the members of the Fort don't share the artcomics audience's reactionary revulsion for comics as collectibles and the dubious effect that such a frequently manipulated system has on the market for more ambitious works. Also appealing for many of the cartoonists is the fact that by making everything by hand, the artist may wield more control over the final product. The original wave of Fort mini-comics therefore married uniquely attractive screened covers to mini-comics' throwaway format. As Robert Boyd points out, their physical appearance also plays a role in determining the artist's choices of what to make and when: "Because it's hand-crafted and difficult to produce, it is impractical to keep the work in print. Boring even; why spend a week silk-screening and hand-stitching another 100 issues of some comic? It's more fun to do a new thing." Cartoonist John Hankiewicz points out that the connection between printmaking and comic goes deeper than presentation and into the works themselves: "In the way some of their marks are made, too, Fort Thunder work is evocative of printmaking. Chippendale with his stamps (the lettering looks like stamps or type) and Ralph with his relief-type line … To the extent that printmaking intensifies your awareness of the physical origin of a mark, the printmaking-like quality of Fort Thunder art anchors their fantasy scenarios in a tactile physical realm - ink, paper, and pressure. In a way, the Fort Thunder print-conscious approach is the opposite of most fantasy art, which is often delicate to the point of being insubstantial." For cartoonist Greg Vondruska, this approach contributes greatly to the unique energy of the work: "I really like the idea of the sort of immediacy and urgency of the mark making of the Fort Thunder group. It's funny that I say mark-making as opposed to drawing, because their drawings are scratchy and sort of dug-out rather than clean. I don't get the idea that these artists make drafts of their comics before they do them."

As a group, the Fort's comics stand among the most compelling works of the last ten years. As individual books, very few reach greatness except in that they suggest a larger body of achievement, an ongoing project of rehabilitating cultural detritus into stories of meaning and significance. Most of what is interesting about the comics comes from a collision of ideas not easily apparent from a surface glance. The silk-screened covers and interiors look accomplished even when they're dashed off in pursuit of artistic effect. What seems like complicated formal play is really a celebration of the basic building blocks of comics language. The unaffected narratives easily communicate highly personal and complicated feelings and beliefs. The Fort artists, while accomplished in terms of craft, remain largely unfamiliar with established comics forms and therefore don't feel a debt to create work within those parameters. Yet while it might be easy to see them as dry and manipulative, they also display, time and time again, a willingness to see comics in terms of its value as junk, as stories, as a pleasurable activity. There is no literary recovery of a fallen art form here, no infusion of narrative tricks from outside media for lofty effect. By concentrating on comics as marks on paper, simple stories, lacking in affectation, the Fort Thunder artists are making works that derive their power from every reason why the form shouldn't work at all. This is an impressive achievement.

Beyond Fort Thunder

Beyond Fort Thunder

One unique aspect about Fort Thunder is that "membership," at least as the public preceives it, beyond the core members has been very fluid. By appearing in various anthologies linked to editors like Jordan Crane and Tom Devlin, Fort Thunder were to be seen as part of the post-alternative wave of cartoonists lightly clustered around Highwater Books. Of course, this made it hard for many people to figure out where the Fort ended and other cartoonists began - Ron Regé, Jr., P. Shaw and Craig Thompson are among those artists considered Fort members by artists responding to questions for this article. Even when you finally establish your list of talents, sometimes you're tempted into talking about the work done by artists at the Fort who barely dabbled in comics. Some of that work has been just as interesting as comics done by cartoonists outside the Fort who devote all of their energy to sequential art. Comics by Andrew Neal ("The Super Fiends") and Matt Obert ("Evil Eyeballs") hint at Fort Thunder's conventionally genre-soaked roots and suggest different avenues that might have been followed by the core artists. Erin Rosenthal's story "Unearth This, Our Bound City" that appeared in an issue of Monster and which has since been archived on the Fort Thunder Web site (with Neal's and Obert's stories) brings a sense of density and inscrutable iconography into play in way that would be familiar to fans of Chippendale and Goldberg. Keith McCulloch's occasional anthology contributions featuring a series of grotesquely illustrated, thin-lined dogs (a visual cross between Drain and Goldberg) are among the wittiest comics to come out of anywhere in the last decade, and feature the same verbal sense of humor one finds in Brinkman, Ralph and Chippendale.

Despite these obvious exceptions, the influence of Fort Thunder on the wider comics world remains difficult to measure. Like the members' best art, the perspective of the onlooker determines to a great extent what if anything ends up being taken away and utilized. Judging by the available evidence, the Fort Thunder cartoonists have enjoyed little influence in terms of content or narrative; there are dozens of wistful, nostalgic and elegantly but sparsely drawn comics - which can be traced directly to John Porcellino of

King-Cat Comix and Stories - and very few cartoonists if any at all who, as Robert Boyd puts it, are doing snake-style narrative like Brian Chippendale. But you can see hints of Fort Thunder influence in Jordan Crane's mini-comics, in Sammy Harkham's approach to line and even in publisher Tom Devlin's rare pieces. Kevin Huizenga claims to see several artists in the mini-comics submission pile for his USS Catastrophe shop that ape the surface elements without getting at the substance of the comics produced by the Fort Thunder crew, while Jason Lutes sees this as another sign of their authenticity: "I think the ripples from their splash are so strong that they are bound to have an effect in ways similar to that of any genuine, original cultural force. Some people will imitate the surface characters of the Fort Thunder work because it's perceived as 'cool'; some people will have a deeper response and take cues from their stylistic approach; others will internalize the spirit of their work and it will bubble up in subtle or imperceptible ways."

There are obvious adherents that can be seen even now - perhaps they're better described as fellow travelers - including many who publish with the Fort cartoonists on various follow-up projects, like

Paper Rodeo. These are the artists most likely to be mistaken as belonging to the original group. In some ways, they seem more "Fort Thunderish" than their predecessors, particularly those who have pursued more fundamentally divergent artistic paths like Lyons and Ralph. The two most important and prolific artists who fall into this category are Ben Jones and Christopher Forgues. Jones combines a fine artist's understanding of collage and color with a predilection for using childhood styles and modes of presentation. Forgues' work offers an idiosyncratic set of visual metaphors that are more opaquely and uniquely his own than perhaps any prolific mini-comics artist working. While many of their works share techniques with other artists - Jones masks his characters and builds his backgrounds reminiscent of Goldberg, while Forgues breaks down many of his comics into component actions and takes on the occasional environmental theme - they are stand-alone talents, and considerable ones. It is best to see them less as cartoonists inspired by Fort Thunder and more as the first among many artists whose work confirms the original Fort Thunder six had discovered a way of working and a set of aesthetic concerns to explore that was bigger and more important than their individual output.

Kevin Huizenga is one emerging cartoonist who has become interested in Jones as his primary avenue for processing the work that's come from Fort Thunder. "Ben Jones' work has always interested me the most," he says. "He has the widest range, is consistently inventive and surprising, and is extraordinarily funny. I think out of all these guys, he's really the only consistently funny cartoonist. He might be the only one interested in being funny. His attitude toward his work is also fascinating to me. He seems to both work hard - he's really put out a mind-boggling pile of books, as well as flash animations - but he also seems to not care, and to make a point of not caring, for his own particular spiritual reasons. He's 'anti-ego.' He used to accept no money for his books, which I thought was misguided but noble. He's generous to a fault. He only makes a few copies of the books and then moves on to the next book." Like many younger cartoonists struck by a particular artists working out of Fort Thunder's recent tradition, Huizenga makes very few distinctions between art and process.

Beyond a scattered few artists paying close attention, there exist a few areas where the influence of Fort Thunder is more diffuse but ascendant. They have without a doubt accelerated an appreciation for different modes of presentation and art direction through their books. There was a time, even post-Raw, where comics could be distinguished simply by working out of the mainstream format box. Chris Ware made an initial impression on thousands of fans through his variably sized

Acme series, the first issue of Walt Holcombe's

Poot shocked some readers with its resemblance to a standard mini-comic and some went so far as to blame the slightly smaller but still very traditional comic-book format used by Michel Vrana's Black Eye Books as contributing to its ultimate downfall. In this context, the choices of the Fort cartoonists, choices that have carried over into their more formal books, have served to obliterate much of the wailing and gnashing of teeth from traditionalists. Why not make a smaller book with different colors in different sections? Why not silkscreen every page? Why not round the corners? Why not make use of the alternative-weekly newspaper page as a standard page unit? The Fort has effectively moved the cutting edge in art direction so far away from the alt-comics regulars that nary a peep is raised in question about the vast majority of books that now deviate from the norm. Fort Thunder made fashionable the idea of presentation as a continuation of the book's art, breaking with years of art direction that catered primarily to the perceived desires of collector-completists and retailers with racking concerns.

Fort Thunder's bigger influence may be in their ability to let cartoonists see beyond very narrow expectations of what comics should look like. When it comes to helping the second and third generations of alternative cartoonists see beyond previous constraints, it's difficult to separate the influence of the Fort myth and the impact that the comics themselves have enjoyed - but exposure to either deepens the feeling that any set of influences, any approach to art, has the potential to become compelling work. This is the same set of feelings that many discover and explore through doing a 24-hour comic or jamming with other artists, just without the rules and inherent game-play. Fort Thunder has told artists and readers there is nothing stopping any comic from being good except the work itself. As Sammy Harkham puts it, "If I want to draw a comic about a tennis player or a talking car or a leprechaun, it can be good - and not in an ironic hokey way, but genuinely … Just be honest with your cartooning and it can work."

The desire to keep working, to keep busy, should serve all the Fort Thunder artists well in future years. The loss of the space, either by leaving or being asked to leave, has brought with it major adjustments for many of the members as they negotiate either side of 30 years old. Living in the Fort not only allowed many of the artists a chance to work and refine their talent, but it suffused those efforts with a meaning larger than any single project: "There was an energy level that was built up," says Brinkman. "It didn't really matter what you were working on. It could be the dumbest little thing, but it felt like a bigger thing." There are other undeniable changes as well - a new family in at least one case, Forcefield apparent dissolution over disagreements on what to do after the Whitney appearance, questions of how much energy should be devoted to pursue new directions and how much to perfect and refine artistic paths traveled thus far. While the mini-comics and collections contain startling works, to a large extent they represent a promising direction that has yet to be fully pursued. The weakest part of Fort Thunder's legacy to comics may be the individual comics themselves, something asserted by several cartoonists replying to questions for this article. Although there are no guarantees, the basic interest in all of the artists to keep working, specifically on comics to varying degrees, is all an audience can ask for. With a readership slowly settling into place that can perhaps better appreciate the artistic avenues to be explored and an infrastructure that should allow for any books to remain in print indefinitely, one has every reason to hope that greater works lie ahead.

Most people claim the building that housed Fort Thunder has already been torn down -- Chippendale talks of standing in the ruins and the still-active fortthunder.org loads with a picture of rubble on its front page - yet it's unclear if this is correct. Some people, including Tom Devlin, claim the building that housed the Fort itself still exists but the building next door has come down. This ambiguity seems an appropriate legacy. The journey Fort Thunder has taken from space into story, from a place to hear bands to a rallying point for a certain freedom to take comics wherever one's inner impulses say to go, to a launching point for perhaps up to a dozen potentially compelling comics artists -- all of this has become more important than the status of even the most clever and lovingly realized workspace. The uncertainty that many of its denizens feel will likely pass, and the art as always should continue. Studios close but artists survive; artists die but the art lives. For as long as the work springs from the hands of its artists, and for as long as other artists pay silent tribute to them in content, style or simply attitude, the best parts of Fort Thunder will always remain standing.