Home > News Stories and Obituaries

Home > News Stories and Obituaries Kim Thompson, 1956-2013

posted July 9, 2013

Kim Thompson, 1956-2013

posted July 9, 2013

Kim Thompson, the iconic co-publisher at and co-owner of Fantagraphics Books, a major figure in the development of North American literary, art and alternative comics, and a well-liked editor, translator and writer about comics, died June 19, 2013 of causes related to cancer. He was 56 years old.

"It would be difficult to overstate the influence that Kim Thompson had, along with Gary Groth, in the modern graphic novel industry," Drawn and Quarterly publisher Chris Oliveros said in a statement presented to

CR. "Along with Art Spiegelman's and Francoise Mouly's Raw Books, Kim and Gary were instrumental in building the foundation for what was then called 'alternative' comics." Writer and one-time co-worker Mark Waid: "No one can convince me that Kim Thompson wasn't one of the most important behind-the-scenes figures in American comics over the last 30 years, nor can they assure me he ever got his due." Longtime close friend and co-worker Eric Reynolds: "A lot of folks in comics thought of Kim as the more silent partner between he and Gary, because he kept a lower public profile than Gary. But he was a towering presence within Fantagraphics, as anyone who has ever worked here could tell you. He is one of the great influences in my life and I'm gonna miss his deep reservoir of knowledge and wisdom in more ways than I can even fathom. He made me better."

"It seems wrong to attempt to sum up his accomplishments so soon," the cartoonist Seth told

CR. "It's almost too early to appreciate the importance of his influence on the world of comics. He should have lived to a grand old age where time would have clearly written out his legacy for us. At the end of a long life it's more blatantly evident just what one has done. Kim was still in mid-career. Not that I'm implying he didn't fully accomplish a life's work. If anything, he did more in 50 years than most people do with 90 or 100."

Kim Thompson was born on September 25, 1956 to John and Aase Thompson. He was born in Copenhagen, Denmark. Thompson's father was a systems analyst, and worked for a variety of employers under contracts of up to a few years in length. The elder Thompson's most consistent employer was the US Army. The Thompson family lived in several different places according to where that work took them: France, Martinique, Thailand, West Germany and Holland. Thompson's mother was Danish, which brought that language into his home as a primary along with English. This was the baseline from which Thompson would eventually come to know and use several languages and employ them in comics translations and business dealings with European comics publishers, creators and printers.

As a small child, Thompson enjoyed a variety of European comics, primarily

Tintin and various Disney funny animal comics. He would occasionally see a superhero comic book purchased at one of the Post Exchanges on the military bases where his father's employment was centered. Thompson became obsessed with Marvel comics as a young teen. This was at the tail end of the initial 1960s Marvel glory years, and the company had instituted a thorough reprints program in several titles. This and the occasional mail-order company allowed Thompson to purchase some version of most of what Marvel had published in its recent burst of Lee and Kirby-led creativity, and thus to grasp the entirety of that company's modern, superhero-driven output. As the company moved into the 1970s, they began to feature younger writing talent at about the same time Thompson was paying close attention to individual styles and approaches on the comics page.

Thompson wrote letters to various Marvel comic books in the 1970s. A list provided by a contributor to Thompson's page on the public-sourced news site Wikipedia gives him credit for publishing commentary in Marvel's

Amazing Spider-Man,

Captain America,

Conan the Barbarian,

Incredible Hulk,

Iron Man,

Marvel Spotlight and

Marvel-Two-in-One titles. Thompson also traded letters with other devoted, engaged, and actively-commenting fans, and at one point belonged to a circle of fans that traded letters and writing, a collection of individuals that included several folks that would eventually become the movers and shakers of the emerging comics generation.

"Back in the 1970s, Dean Mullaney -- later co-publisher of Eclipse -- approached several of what were then called Marvel 'letterhacks' (i.e. frequent contributors to Marvel's various letters columns) to correspond privately with each other -- through snail mail, of course, because in those days that's all there was. Looking back, it was like a precursor to chat rooms," the writer Robert Rodi wrote to

The Comics Reporter. Dean Mullaney added in a different correspondence, "Our pen pal group in the 1970s included Kim, Ralph Macchio, Rob Rodi, Mary Jo Duffy, Jack Frost, Jana Hollingsworth, and me, among others." He added, "Most of us aspired to become comics pros. What particularly fascinated us, in general, were the new group of writers at Marvel who were expanding comics in entirely new dimensions -- writers such as Steve Gerber, Don McGregor, Steve Englehart and Doug Moench."

"Love of that era's Marvel Comics was what united us, but our conversations ranged very far afield," Rodi reported. "We were geographically, socially, and culturally very diverse -- though as our group became more enmeshed, Dean realized that we were all male. He asked what we thought about asking Jo Duffy and Kim Thompson to join, and we all agreed. Kim accepted at once, and made up for the disappointment of actually turning out to be male by bringing great wit and

élan to the circle, and a knowledge of European comics that put the rest of us in the shade."

Another member of that general, active fan community was the late prominent Marvel editor Mark Gruenwald, like Thompson's eventual business partner Gary Groth a devoted fanzine maker. Thompson seemed to have been only lightly involved in that specific comics culture relative to his letter-writing habits, contributing to a few publications here and there such as

Omniverse and

Woweekazowie. The Fantagraphics blog in 2011 threw a spotlight on one whimsical effort

here.

Thompson's entry into the world of comics may have been slightly atypical for his fan peer group, many of whom took more established office-job and freelancing options with mainstream comics companies. Thompson used an acquaintance in that larger fan community to meet Gary Groth upon moving to the United States in 1977. He immediately began working for the fledgling company, called Fantagraphics, then based in the larger DC area from which company co-founders Mike Catron and Groth hailed. To be as specific as possible, the company was located in the spare bedroom of Groth's College Park apartment. Both Catron and Groth have described in subsequent interviews that Thompson basically just showed up and started working. Thompson contributed money to the struggling company that next year, a small amount of cash diverted from an educational fund given to him by his grandparents. Although there have been differences of opinions expressed as to whether or to what extent this constituted Thompson's actual, formal bid for part ownership, it was clear he was wholly invested with the company within months of beginning to work with them. He had found his life's work.

In those days, the business of Fantagraphics was

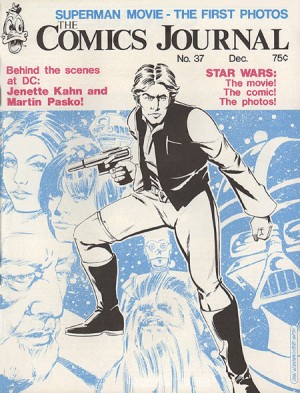

The Comics Journal. Thompson quickly became a presence within the magazine as a reviewer and interviewer. According to former

TCJ managing editor Milo George, Thompson's first credited issue of the magazine was #37, the first "modern" issue of the magazine from its

Nostalgia Journal and tabloid format beginnings. As a critic, Thompson took a rigorous look at some of the higher-end genre work that had attracted him to American mainstream comics in the first place, including a famously tough review of writer Don McGregor and artist Billy Graham's

Detectives, Inc.:

Marshall Rogers's work on this book is a huge disappointment. Oddly enough it is not so much a case of McGregor dragging Rogers down to his level as it is of Rogers being out of his depth.

Rogers, who studied as an archiÂtect before turning to comics, had produced some handsomely designed work for, coincidentally, Detective Comics, as well as a handful of other mainstream projects before turning to this. Unfortunately, Rogers simply cannot draw very well anything that cannot be broken down into blueprints; in a story where the human element is not only the core, but virtually the totality of the story, McGregor has been saddled with an artist who is incapable of drawing the human face and figure. Rogers' work in this area is at times staggeringly bad: there is not one body in Detectives, Inc. that is not stiff, cold, and awkward-looking, and they all have heads that are too small, making them look nine feet tall. The facial renderings are horrendous: every character is afflicted with a blank, unfocused stare, a mouth that hangs limply open, and gestures that generally don't seem related to one another (in one, panel, Rainier's ex-wife is shown facing the 'camera,' but her nose is in profile). For some reason, every single character in the book has this incredibly long, thin nose -- even the blacks, who look like curly-haired Caucasians with zip-a-tone all over them. Worse, no one looks the same from panel to panel.

One memorable piece he contributed to the

Journal in those early years was the magazine's first full-length interview with the cartoonist Dave Sim. Thompson championed Sim's comic book

Cerebus almost from its conception, and would remain convinced of the cartoonist's skill -- if not various, specific beliefs Sim held -- for the remainder of his days, even offering to publish certain works of Sim in recent years (Sim debated and then declined the offer). The Sim interview ran over two issues, and featured a cut-in-half cover. It was likely

not the first interview in the magazine anticipated as "

The Comics Journal doing what they do with this specific cartoonist," given the publication's impressive run with a variety of mainstream comic book figures ranging from the fully-invested executive to the strictly iconoclastic creator, but the Sim piece was early as the magazine began to secure a reputation for longer, more serious talks with an emerging generation of cartoonists increasingly looking to the comics medium in terms of its opportunities for personal expression. The choices made by the publication were not automatic, even though they look inevitable in the rearview mirror. Thompson and the rest of Fantagraphics ran the risk of routinely alienating the professional community on which the magazine depended for advertising revenue, a significant chunk of its readership and access to interview subjects.

For critic Jeet Heer, Thompson's writing contributions were directly vital to the magazine's growing sense of mission. "When I started reading

The Comics Journal circa 1980, Kim Thompson was among the most important 'voices' in the magazine, along with Carter Scholz, Gary Groth, R. Fiore, and Dale Luciano," the writer told

CR. "What characterized Kim's criticism was clarity of expression, candidness, and an erudite familiarity with the cartooning traditions of many nations -- which was even more rare 30 years ago than it is today. He was equally good as a negative and positive critic. He could acutely debunk certain over-praised works and locate their problems -- say Don McGregor's

Detectives Inc. or Frank Miller's

Ronin. But he could also pinpoint the reasons why Harvey Kurtzman's war comics have stood the test of time, an analysis that went to the brass tacks of the storytelling including sharp observations about Kurtzman's sound effects."

Thompson's early work at

The Comics Journal was the starting point for a significant, career-long sideline in writing about comics: for the magazine, for other Fantagraphics publications, and later on-line. While the majority of Thompson's time in comics was spent away from the writing-about-comics camp, particularly as Fantagraphics expanded, Thompson's writing has always been welcome and still has its fans. "Kim was a generous writer," current TCJ.com co-editor Dan Nadel wrote

The Comics Reporter. "He seemed to want to educate the reader by explaining, in a very matter of fact way, not only what made a particular comic work but also the context -- historical and aesthetic -- in which it worked. And best of all he really knew and could describe that context." Nadel mentioned he was a particular fan a series of "Editor's Notes" for the Fantagraphics blog that Thompson wrote about various subjects tying into new releases, sometimes employing an interview format. Nadel was constantly on Thompson to contribute to the flagship publication itself.

It appears Thompson's last major piece of writing for the

Comics Journal site was

this obituary for Moebius, his last piece of critical writing for the Fantagraphics blog was likely this piece on

New York Mon Amour, and in terms of

The Comics Journal's print iteration

a major interview by Kim Thompson with Jacques Tardi ran in the recent

The Comics Journal #302.

Fantagraphics moved from College Park to Connecticut in 1979 in order to be closer to the industry that their lead publication covered. The company and its growing staff settled into a large house near Stamford where many on staff both lived and worked. This included Kim Thompson.

Asked how Kim fit into the young company's overall culture, particularly its three-headed brain trust of Groth, Catron and Thompson, Mike Catron told

CR, "Kim was the

noodge. Kim was always into everybody else's business. Whatever projects Gary was working on, or what I was working on, or whatever anybody was doing, if Kim suddenly took an interest in it he would find a way to insert himself into it in some capacity. He was vitally interested in everything that Fantagraphics did, even if it wasn't one of his books. He made no bones about it and he did that because he wanted to make sure that the project was as good as the vision he had for it, even if it wasn't his project." Catron laughed. "And it sometimes drove people crazy."

The publisher remained vastly under-capitalized. Its owner-employees and the incrementally-growing staff worked past many of the issues brought on via operating so close to insolvency by investing an enormous amount of personal time and effort. This had started in Maryland -- during which Groth, Catron and Thompson also held day jobs -- and continued in Connecticut. "No one worked harder than Kim, and he expected everyone to hold themselves to the standard he held himself to," explained Tom Heintjes in a statement to

CR. "I remember when I joined Fantagraphics in May 1984. They were still in the house in Stamford, and several of us lived in the house because we couldn't afford rents elsewhere. So everyone pretty much slept or worked. Kim was a machine -- setting type, copy-editing, coordinating deadlines with creators, paginating books, working with printers, some of everything. Gary was a big-picture guy, establishing the overall vision, but Kim was the guy with his sleeves rolled up, working on the nuts and bolts. He would lie on the floor and make sure the books' signatures worked out correctly, all those production-related issues. Pretty much his 'work uniform' was a pair of gym shorts and a T-shirt. It was many months before I saw him wear anything else... I think it might have been the party we threw when we were leaving Connecticut to move to California. He worked very intensely, which we all had to do because of the small staff and the large amount of work."

One highlight of the Connecticut era for the company was starting the magazine

Amazing Heroes, in order to take better advantage of the opportunities to serve superhero fans that had formed under the growing direct market of hobby and comics shops. The cartoonist Frank Santoro, a fan of the publication, described

Amazing Heroes in succinct terms for

CR: "It brought the same high-brow approach to comics that the

Comics Journal had but did so without making fans feel silly for liking superheroes." Thompson would later in an interview for the unpublished

Comics As Art... We Told You So company history admit to slightly less lofty goals: to cadge ad revenue that was going to other publications, a mission he says

Amazing Heroes largely accomplished. The publication remains a curious bridge between straight-up fanzines and ad zines and the slicker, once hugely profitable, men's magazine-reminiscent

Wizard.

The in-house instigator for the

Amazing Heroes project was actually Mike Catron. He had difficulties from the magazine's founding in terms of keeping up with the necessarily strict deadlines. The magazine soon fell to Thompson, who with a series of co-editors kept the publication, which generally ran from 64 to 88 pages, on a startling, at-times bi-weekly schedule for almost a dozen years, including several over-sized specials and theme issues. To do this and remain as involved with other aspects of the company is one of the major feats in modern comics publishing production history and speaks to Thompson's terrifying facility as a writer/editor and to his general work ethic.

Calling it "the comics news magazine for unabashed hero-worshipping fans," the writer and academic Charles Hatfield remembered

Amazing Heroes as a key part of the company's history and something for which Thompson should be better known. "The eventual death of

Amazing Heroes in 1992 was an inevitable sign of Fantagraphics' growth, but for quite a few years the magazine provided, again, a smart alternative to the adzine and

Buyer's Guide sort of journalism that had come before it.

Amazing Heroes was the not-so-hardnosed cousin to

The Comics Journal, good cop to the

Journal's proverbial bad cop, and a brighter, friendlier mag. Maybe it was a compromise, but it worked: it helped Fantagraphics navigate the direct market, and positioned the company relative to what was going on in the weekly world of comic book retailing. That was vital. I'd say

Amazing Heroes was the unacknowledged other part of the

Journal's history, though officially and editorially the two magazines were just that, two separate magazines. The

Amazing Heroes previews were mouth-watering coming attractions for months and months of promised comics, and I remember poring over some of them with pure, uncut enthusiasm.

AH also ran smart interviews and nostalgic comic book history, tastily written, without condescension or bias. Kim's long, long editorial run on that magazine, an under-acknowledged part of his career, was a great, gracious balancing act."

Mark Waid worked on

Amazing Heroes for a brief period starting in 1986, after Fantagraphics had moved to the greater Los Angeles area. He recalled the publication and its reflection of the broader tastes of Kim Thompson in an e-mail to

CR. "

AH was Kim's long-standing thorn in Gary Groth's side, a publication Gary loathed partly because he was very cynical and elitist about mainstream comics, partly because it was the company's main source of revenue. But Kim never let it rattle him and, on occasion, would confess a secret joy in being able to get under Gary's skin with it. A good-natured 'sin,' because -- as I admired -- Kim was almost wholly without malice. He was positive, he was a problem-solver, he didn't have much use or time for grudges, and his smiles and laughter were genuine. When I came to work at Fantagraphics for about seven minutes in 1986, Kim was my boss and became my friend in short order; in one another, we'd found a kindred spirit who could enjoy Greek literature and the TV show

Moonlighting in equal measure, to Gary's eternal disparaging despair." (

Amazing Heroes contributor Heidi MacDonald told

CR the TV show she and Thompson discussed most was

Hill Street Blues.)

Fantagraphics moved more fully into comics publishing in the early '80s, starting with the stand-alone

Flames Of Gyro featuring neighboring Connecticut talent Jay Disbrow and quickly moving into a selection of high-end genre comics. This meant opportunities for Thompson to edit actual comics content, another significant, career-long contribution he would end up making to the industry in which he worked. While Kim's editorial duties would eventually include work with cartooning luminaries such as Peter Bagge, Chris Ware, Joe Sacco, Stan Sakai on both solo titles and more than one iconic comics anthology, he started out in Fantagraphics editorial much more modestly and in some instances remained so: Thompson was credited as an associate editor or editorial coordinator on early Fantagraphics comics efforts such as

Dalgoda and

Journey, perhaps a reflection of the collective ethos of the company. He would later hold not-quite-full-editor titles on Fantagraphics anthologies to which he provided material and assistance without being the publication's main driving force, such as a contributing editor title on the humor-focused

Honk!

Thompson arguably became first known as an editor when he became the driving force behind the funny animal anthology

Critters, which for its longevity and the general quality of its features during a sustained period of anthropomorphic comic books being published in the US remains one of his specific, lasting legacies. Thompson tapped artists comfortable working within that tradition such as Stan Sakai and Mike Kazaleh, accessed a few key works from other countries, and even at times encouraged contributions comics-makers known for other kinds of work entirely, such as the cartoonist Ty Templeton, as described

here. Like much of what Fantagraphics published,

Critters represented a specific idea that Thompson wanted to see made real. It's worth noting that any number of Fantagraphics projects over the years -- including many of those directed by Thompson -- came down to