Home > CR Reviews

Home > CR Reviews Snow Piercer Volume One: The Escape

posted March 10, 2014

Snow Piercer Volume One: The Escape

posted March 10, 2014

Creators:

Creators: Jacques Lob, Jean-Marc Rochette, Virginie Selavy, Gabriela Houston

Publishing Information: Titan Comics, hardcover, 110 pages, January 2014, $19.99.

Ordering Numbers: 1782761330, 9781782761334

This very, very handsome presentation of the 1982 graphic album

La Transperceneige by Jacques Lob and Jean-Marc Rochette likely owes its existence to a recent Bong Joon-Ho film adaptation starring Chris Evans, Tilda Swinton, Ed Harris and a cast of capable film veterans. That came out last year internationally and is currently held up in a bit of dispute by the Weinstein Company's unfortunate desire to want to cut work to improves its box-office chances; it will see a release in the summer, having made about $70 million in international markets. It's old-school science fiction: after a global weather catastrophe instigated by a weapon used during a nascent war, the planet's likely sole human survivors run a circuit on a massive train. A man from the lowly, tail end of the train moves towards the front where he instigates and uncovers in equal amounts a plot against the back half of the train. It's a giant, ponderous, and wholly blunt metaphor: class warfare played out on a limited stage where every player is thus important not just for the foregrounded situation but because they literally represent the future of humanity. It's easy to see a film here, and to project the original album's success, and to figure out why there were a pair of sequels (gathered into a single, second volume) by other talents working in the same mode of presentation. There's an audience for science fiction that's About Things, and this is certainly that.

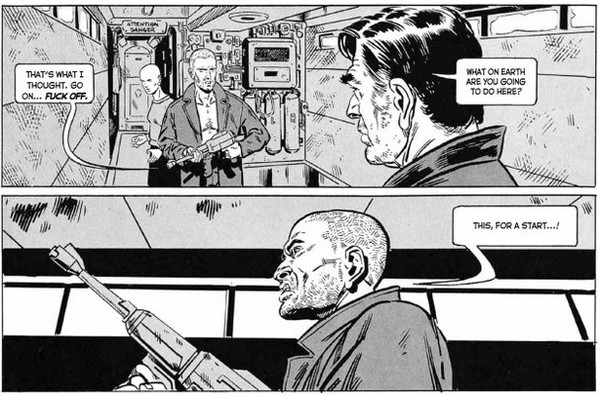

While I imagine the reviews for the re-release will be mostly positive, the book had a hard time holding my attention. For as much as I can see people trumpeting its grim vision of human nature as a sort of left-turn from a heroic version of the same story, I find what was executed on the page to be cliches of a slightly more serious-faced type. Every time a character introduced themselves -- surviving man from the back of the train eager to see to his own interests, idealistic woman that wants to help him, pompous bureaucrat, weathered soldier, acerbic doctor -- it was hard not to respond, "Well, of course you are." That this was the kind of book where a string of characters introduce themselves was another sign I wasn't going to find a whole lot here that interested me except maybe the broadest, allusive strokes. Nothing any of those characters did after those introductions surprised, except in perhaps the central metaphor being so sturdy and obvious that I thought they would do more with those in the train just generally in terms of providing a variety of reactions to the basic situations that presented themselves. "Fascinatingly dull" comes close to what we got instead. The most interesting element of the setting was by far the way limited information was employed up and down the train cars. In strong contrast to the life we have now where a constant barrage of information must be sorted, and also in contrast to one moment in the narrative where a radio is employed to bring a moment of truth directly from one set of charcters to another, those on-hand cling onto such limited scraps of intelligence and such rudimentary narratives that they could manipulated in ways that were almost heartbreakingly child-like. The visual approach of varying three-tier pages in a way that suggests the emergence/push-through of walking through train cars I also thought cleverly employed.

The original work's ending reveals our hero's importance less for the the specific experiences he had than for its broader meanings, and then quickly suggests that even that's not crucial, that his primary function was to carry some sort of flu bug through the train, and then one more time suggests that he himself is some sort of virus whose basic presence on the train is enough, even as we wonder after its eventual end. It nearly makes the stock situations and central casting feel of the early chapters work, that this final rug can be pulled out from underneath the whole idea that any character has agency that means much of anything in the wider scheme of things. When your metaphorical construct is a stand-in for humanity, that's a depressing place to go, and it is underlined by some work the authors did throughout in making a value out of being alone on the train when the pressing horror of the human condition and the danger in the milieu presented stems from isolation. This also made the sequels very hard to read, as they seemed like sideways riffing on an original idea whose first outcome holding sway over possible others was the point, and that a second take on the same basic situation couldn't help but diminish the first. I did like the more tightly cramped pages, particularly on the interiors, and some of the individual ideas floated intrigued me, but the second, equally handsome book felt to me like planting mushrooms in a corpse.