Home > Bart Beaty's Conversational Euro-Comics

Home > Bart Beaty's Conversational Euro-Comics Mon Fiston, Olivier Schrauwen

posted October 29, 2006

Mon Fiston, Olivier Schrauwen

posted October 29, 2006

I don't much more about Olivier Schrauwen than what is written on the back of his new book,

Mon Fiston (Editions de l'an 2). He was born in Bruges in 1977, studied animation at K.A.S.K. and comics at the Institut Saint-Luc in Brussels. He works primarily as an animator, but has published comics work in

Spirou,

Robbedoes and

Hic Sunt Leones (which I reviewed here about a year ago). Oh, I also know that he's some sort of postmodern comics genius.

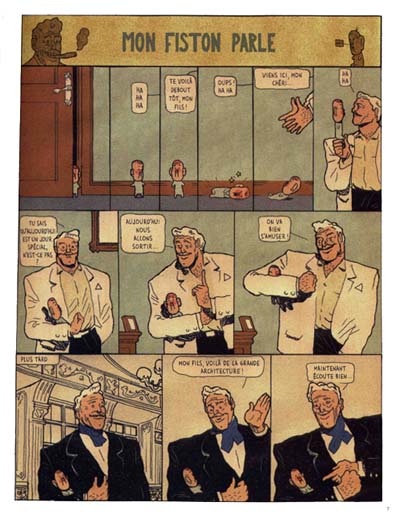

Mon Fiston, Schrauwen's first book, a knowing pastiche of early twentieth-century comics influences, is one of the most provocative comics I've read this year. What it lacks in length and scope it more than makes up for in subversive, obsessive depth.

Mon Fiston, with its simple, strange short stories, is a book like few others. Its retro sensibilities are so pronounced that it reads like an undiscovered classic, like something from the pages of

Art Out of Time. Yet, at the same time, it is so thoroughly contemporary in its critique of turn-of-the-last-century masculinity and image making that it also seems utterly contemporary.

Throughout the five short works in the book, Schrauwen channels the spirit of the masters.

Mon Fiston opens with a short wordless story about the birth of a young boy. Reminiscent of nineteenth-century proto-comics (no panel borders, grayscale, grand satiric gestures and broad melodrama), the first story sets the stage for the entire book. A wealthy man becomes a proud father, but loses his wife in the process. The rest of the book examines the surreal and nightmarish relationship of father and son.

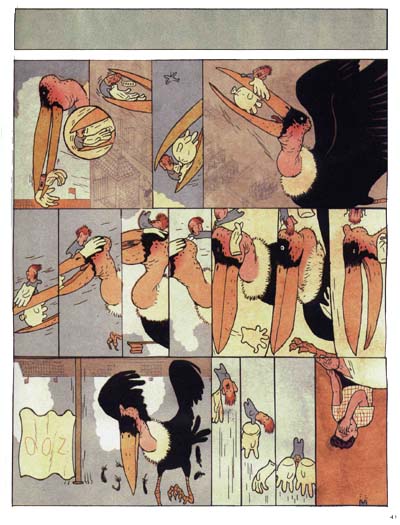

Clearly, Schrauwen's most obvious influence is Winsor McCay, whose style he apes throughout. The artist nails this tribute, with the quivering and strangely shaped word balloons, the muted color scheme, awkward panel sizes and arrangement, and the dream-like landscapes. The best story in the book finds father and son on at trip to the zoo, where the son (who is always drawn inappropriately small) is swallowed by a crocodile. Inside the belly of the beast, the boy is rescued by a pygmy, and is later caught up in a wide-scale pygmy revolt that sees the release of all the animals. Chaos ensues, including a man battling a giant ape, the flight of a vulture, and an amazing set piece in which the pygmies join forces to battle the police. As a story it is witty and sharp. As a commentary on the origins of the medium it is powerful and trenchant.

Schrauwen in no way shies away from the problematic imagery that structured early comics production. His pygmies are a cutting allusion to the influence of late-colonialist representations of Africans, and he further highlights the absurdity of turn-of-the-century bourgeois masculine codes. In this way, Schrauwen celebrates artists like McCay while problematizing our relationship to a comics heritage. His humor is a double-edged sword, and all the better for it.

Mon Fiston, translated from the Dutch by Thierry Groensteen, is scheduled for an English-language release from Bries some time soon. Put it on the shelf next to

So Many Splendid Sundays.

*****

To learn more about Dr. Beaty, or to contact him,

try here.

Those interested in buying comics talked about in Bart Beaty's articles might try

here or

here.