December 23, 2013

CR Holiday Interview #07—Dean Mullaney

CR Holiday Interview #07—Dean Mullaney

*****

Dean Mullaney is a key figure in comics publishing's greatest generation, a group of devoted fans born after World War 2 that helped reshape an industry devoted to profitable junk to favor the best art in its midst and to encourage the creation and inclusion of more. The

Library Of American Comics, his venture with

Bruce Canwell,

Lorraine Turner and

IDW Publishing, is one of the agreed-upon good things in modern comics, providing high-end reprints of the best of the classic comic strips while at the same time facilitating a greater critical and biographical understanding of strip creators. He is also known to comics people of my generation and older as co-founder and co-owner of

Eclipse Enterprises (later Eclipse Comics), one of the key publishers of the independent comics movement of the 1970s and 1980s. A lot of what adult readers enjoy about comics now had an antecedent or early example at Eclipse. Mullaney has taken the "I can live anywhere" opportunities of self-directed employment more seriously than some, making a home in

Key West. Like many discussion between two older men, we started out talking about the weather. I tweaked what follows for flow. -- Tom Spurgeon

*****

TOM SPURGEON: One way to enter into our conversation: you announced a Bobby London-era

TOM SPURGEON: One way to enter into our conversation: you announced a Bobby London-era Popeye

book the week we're talking. I wonder if that might provide us with a snapshot as to how you guys select and then orient yourself to a new project. How does that work? Did someone bring that work to you? Did the notion enter your head at some point? Is this something you always wanted to pursue? How do you progress from concept to announcement?

DEAN MULLANEY: There are more books that I want to do than I'll ever have time to do. My main interest is 1930s and 1940s strips, but I'm interested in good strips from every era. I've always liked Bobby's work. At the time, King Features' choice of using him on

Popeye seemed odd to me. But it was fantastic. I didn't see it all the time. It wasn't in my local newspaper. It's one of those runs that everyone wants to see but nobody has seen except for that one small collection.

One nice thing about running the imprint is that I can basically do what I want.

SPURGEON: [laughs] So at what point does a project become a priority, does it start to progress towards publication? Are there ease-of-production issues? Do you move forward once you know you can get a hold of something?

MULLANEY: Obviously you can't publish a book if you can't find the material, but the biggest factor I have now is trying to find room in the schedule to add books. On average, we have two books a month on the schedule. I'm looking at next June -- we're going to hit release #100. That's a lot of titles. I have a piece of paper in front of me, since I still like to keep my schedule on a piece of paper rather than a computer... I'm filling in holes up to the end of 2016.

SPURGEON: My goodness.

MULLANEY: At the bottom of my sheet I have 12-16 one-shots that I'd love to do, and I'm trying like hell to find a hole for them.

SPURGEON: So the LOAC Essentials series, like the book of strips from The Gumps you did this year, people have always talked about that line to me in terms of you guys hedging your bets over something that may or may not sell. But am I to take it it's also a factor that there's value for you in having a line where you don't have to make a full commitment to all of a strip because that means you can actually put out more works?

SPURGEON: So the LOAC Essentials series, like the book of strips from The Gumps you did this year, people have always talked about that line to me in terms of you guys hedging your bets over something that may or may not sell. But am I to take it it's also a factor that there's value for you in having a line where you don't have to make a full commitment to all of a strip because that means you can actually put out more works?

MULLANEY: It's not a matter of something not selling in another format. There's some strips that I think you don't need to see 40 years of it. To me, 40 years of

The Gumps is like I'd be snoring after the top five years. The same with

Bringing Up Father. I

love [George] McManus' work. We've done two books so far, and we'll probably do a third one. But do I want to read 50 years of it? No. To me... some strips you just want to present the best years of the strip. With something like

The Gumps, what I'm hoping is we'll be able to do two more volumes of

The Gumps, and pick two years: maybe the one where Andy runs for President, or something like that.

The concept behind the Essentials for me is exactly what Bill Blackbeard was doing with the Hyperion Line. That was the late '70s, so I was in my 20s when those books were released. Bill's concept was that if you were going to have a comics library, and if you're not going to have an expensive comics library but you still want to have one, then these are the books that you need to have in your library to understand the full breadth of the history of comics.

SPURGEON: You talked in an interview with Tom Mason a few years back of wanting to do collections of Terry And The Pirates as long ago as the early 1980s. I wonder how much of what you get to do now is based on your experiences of seeing what other publishers have done with similar material, what the other attempts have been. I wonder if there's been some sorting out of what you've liked and what you haven't liked -- for instance, if you liked a quality of a book Bill did, or if you didn't like someone else's approach in a certain way. Do you have the benefit of picking and choosing what you thought worked and didn't over the preceding quarter-century?

MULLANEY: That's not really a consideration for me. The reason that Bill's efforts were influential on me is that he introduced me to all this material. So obviously, any of the other publishers that release work, like the early Frank King

Gasoline Alleys, I never knew how great that stuff was. I think most of us didn't. So obviously certain series will introduce and allow us to re-evaluate certain creators. I hope to be doing that with Sidney Smith; I hope we're doing that with Cliff Sterrett. What I choose is what I've seen and what I like and what I think other people will like, too.

SPURGEON: Correct my memory here. A moment I remember encountering you early on in the imprint's days was when you had a mock of the Noel Sickles book. It was a San Diego, and IDW had secured a little room for meetings and you and I went through the Sickles book. The Caniff work... did the Caniff work you've, the reprints, did they come before the stand-alone Sickles? Because the dates says it did, but I always remember the Sickles book as

SPURGEON: Correct my memory here. A moment I remember encountering you early on in the imprint's days was when you had a mock of the Noel Sickles book. It was a San Diego, and IDW had secured a little room for meetings and you and I went through the Sickles book. The Caniff work... did the Caniff work you've, the reprints, did they come before the stand-alone Sickles? Because the dates says it did, but I always remember the Sickles book as the

early book for you. I wonder if I'm just fudging the dates because the Sickles book was so interesting to me.

MULLANEY: Terry was the first, and I decided that because it was my coming back into comics... over the years we've all seen people publish series that stop after the second one, or after the third one. So with

Terry, it was important to me not to just do it and do it the way I wanted it to be done, but release it on a quarterly schedule so that people would think, "Yes. This is definitely coming out." You don't want to buy a series if you don't know it's going to be completed.

The second series we started was

Little Orphan Annie and the Sickles book was released shortly thereafter. So it would have been the third different strip we added to the line.

SPURGEON: The Sickles book was a remarkable book, I think, in great part because of the sheer publishing chutzpah involved in putting a $50 Noel Sickles book out into that market.

MULLANEY: When Bruce Canwell and I went to Ohio State to look at the Sickles papers, it became immediately apparent to us that no one had really researched the Sickles papers since his widow had deposited all the materials. Everything was in the same boxes and in the same order as it had been deposited in. There might be something related to the

Saturday Evening Post in this box or in that box; nothing was collated or organized. We had virgin territory; it was fantastic.

The original idea was to reprint the complete

Scorchy Smith for the first time, and maybe have a 40 page introduction about Sickles. We ended up finding so much unbelievable material it turned into 140 pages and the binding of the book was falling apart. [laughter] It's essentially two books in one.

Would I do it another way? No, because I think it belongs together. We could do it as two books and put it in a slipcase... we just found so much material to add in. That's what we do with the entire line. If we need to add 24 pages or 32 pages to a book, even 100 pages, because it needs it, we do it. You don't get a second chance at doing this.

SPURGEON: The Sickles story I wanted to know about... I heard that you tracked down original Scorchy Smith

material right up to date of publication. That is like a little-kid version of how I think strip collections should work. Did you really find vital material at a small-town newspaper very close to press?

MULLANEY: Yeah. We were down to... I think two strips we were missing. We had really crappy microfilm for them. We were going to go with it. We were going to go with the microfilm rather than have a hole in the book. We had maybe two weeks to print. The same thing happened with the first

Blondie book... we were missing a couple from the first few weeks of

Blondie. Either it's my luck or my tenacity but so far we haven't published a book with any holes in it. We've come right down to the deadline on probably half a dozen books including the first Superman Silver Age dailies. Those we just found just a couple of weeks before publication. I'm always optimistic. I'm always optimistic we'll find the strips if we just contact enough people.

It's not like the old days. I remember years ago at Eclipse I reprinted the

Johnny Comet strips. We would send letters -- this was obviously before the Internet -- so we would send letters to a collector in Austria... You'd have to wait a few weeks for the letter to get there. [laughs] Then the guy sends you a letter back. Maybe he has access to a stat camera, and maybe he doesn't. It's a lot easier to find material now.

Some strips are still almost impossible to find. We're going to add a volume in the Essentials of

The Bungle Family. That's a really hard to get a complete set of. I have about ten or twelve years since I've been collecting it. Some strips are very hard to find.

SPURGEON: What makes that one to find? Was it the number of papers it was in? The kinds

of papers it was in?

MULLANEY: I think because of the syndicate it wasn't in major papers, but that didn't stop people from clipping other strips. I just don't know. I don't know why certain strips are harder to find than others.

SPURGEON: Do you encounter the post-war difficulty of shaving strips? I edited the paperback series of Pogo strips that Fantagraphics did, and Bill Blackbeard's strips were unavailable. We had a good collection of clipped strips, but into the early '50s the newspapers themselves would crop the strips. Like cut off an 1/16 of an inch strip on the bottom to make it fit on the page. That seemed like a post-War thing... at least with that feature.

MULLANEY: That actually started in 1941, I think, or 1942. I encountered it with

Terry And The Pirates with our

Complete Terry. I'm always going for the full version of it, but there's about I would say three months worth where the strips have the bottom -- I'd say the bottom quarter-inch or so -- cut off. That was for newsprint considerations because newsprint was hard to come by and rationed during the War. The syndicates and the newspaper used that as an excuse after the War to keep the comics small so they could fit more comics in there. That's a perennial problem in trying to assemble complete sets of strips.

In the

Steve Canyon set we're doing now we're using full versions. But what Denis Kitchen had access to years ago was the cropped versions. Caniff particularly... it changes the entire composition and look of the strip when the bottom is cropped. Granted, all these artists knew their work was going out in two formats. They didn't want to put anything important down at the bottom. Somebody like Chester Gould would put a lot of black and dead space in there. But Caniff would add interesting information, interesting artwork. It also makes the balloons wordier -- it changes the look of each daily, it changes the look when the balloon takes up more room relative to the rest of the strip.

SPURGEON: I know with the Walt Kelly strip a lot of dead information was down there, but the cropped versions just looked awful.

MULLANEY: You can only print what you can find. Whenever we can find the full versions, we use them. If we can't, we have to use the cropped version. It's still a real version, a legitimate version; it's just a different version.

SPURGEON: How much institutional support do you get, Dean? Are the syndicates helpful? Are the collectors? What about the universities? I know that Billy Ireland makes their work as available as they can as an explicit part of their overall mission. But I also know that all academic institutions haven't always had that reputation. Have you had good support from schools, collectors or the syndicates themselves?

MULLANEY:

MULLANEY: The syndicates don't keep much. We've gotten a few things from King Features. A few years ago King Features digitized what they had. The quality of the digitization -- I"ve seen some of it that's fantastic and some of it leaves a lot to be desired. I think it's more for reference for them than anything else. Do they really need every strip from a feature from the 1930s for licensing purposes? I doubt it. They donated the original syndicate proofs to both Ohio State and Michigan State. When I need

Rip Kirby strips, I go to Michigan State and make copies of the strips at Michigan State.

The Tribune Syndicate had some proofs, but not many. They've moved so many times over the years. From New York to Orlando and now in Chicago... some things have disappeared over the years. We have access to most of the

Little Orphan Annie proofs and

some of the

Dick Tracy proofs, but not much more.

SPURGEON: Another basic question I have is I wonder if the time passed is starting to become an issue now. With families, you're starting to get into subsequent generations for whom a strip the patriarch might have done wouldn't loom as large in their lives, so they might have a different attitude towards taking care of this material. Even collectors might not be as naturally inclined to collect a lot of the older stuff as they used to.

MULLANEY:

MULLANEY: We're still close enough in terms of generations... like

King Aroo, Jack Kent. Jack Kent Jr.... his father saved all the art -- for the most part, except for the later stuff -- and it was all in a pole barn in back of the house. It was sitting in this outside pole barn in San Antonio, Texas. Surprisingly, the art was still in fantastic shape. Luckily, he had it. He knew was it was. He didn't know necessarily what to do with it, even how to sell it. It's made available to us.

In terms of collectors, it's amazing how many people would clip a strip for an entire year back in the '30s and '40s. I remember a story that Steve Ditko's brother told us when we were researching a Steve Ditko bio many, many years ago. He said that his father worked -- I think it was in a mill -- in Johnstown, Pennsylvania. And he was so busy he didn't have time to read the Sunday comics. So the family would cut the Sunday comics out and for Christmas each year the mother would sew them up into a bound volume so that over Christmas vacation the father could read a year's worth of Sunday comics.

SPURGEON: Wow.

MULLANEY: That's fantastic. That's an amazing story. That's where my

Bungle Familys come from. I've got a set of

Bungles from the

Kansas City Star. Somebody clipped them out. Somebody clipped them out, and either saved them for themselves or for somebody in their family. They keep popping up.

SPURGEON: Maybe The Bungle Family

is a way to get into something that interests me... it seems that The Bungle Family

might be more

relevant now that it was even 20 or 30 years ago. There's something about the acerbic nature of the strip and the cantankerous relationships on display that might work better now than it might have a generation previous. There might be an audience for the type of material just for its tone and approach. And there are strips that seem harder to process at certain times... I think we may be going through that with Pogo

right now, which is a strip that is very much a confluence of various aspects of 1950s American culture. It's not that it's so far behind in the rear view mirror as it is that a number of factors put us out of touch with the context in which that strip hit so hard with its audience.

MULLANEY:

MULLANEY: I agree with you on both counts.

The Bungle Family, because of the acerbic nature of it, it's more quote/unquote modern in 2013 than it would have been 25 years ago.

Pogo was more hip 25 years ago than it is today. That in-between period of the past. It's not

really in the past, which makes it fascinating, it's not yesterday but in-between time. That's always a consideration. We all... whether it's me, or Fantagraphics or Drawn and Quarterly or Charles Pelto with Classic Comics, we're all looking at the long picture. We're not looking at what might be popular in 2013. We're doing this not for the money but because we love strips and want to preserve them and we have this fantastic window right now. It's truly, truly a golden age for strip reprints. There's more stuff reprinted now than any of us ever hoped to imagine would be. So we take the long term.

I'm doing the same thing with the Essentials. Is

The Gumps going to be the best-selling thing that we ever did? No. Will it lose money? It will probably break even over time. Will

The Bungle Family be a best-seller? No. But they're important strips to do. We can afford to do them.

SPURGEON: Is it different at all doing later volumes of a work? Little Orphan Annie

and I'd say even Dick Tracy

, too, they seem far enough long in their respective series that the feature itself might have changed. Are there unique challenges to doing later volumes in a series that you don't have with a one- or two-shot or even the initial volumes of a longer series?

MULLANEY: Oh, sure. It depends on the strip, too. With

Annie, I just read ahead until the end of the '40s. During World War 2, when she gets into the Junior Commandos, it's not necessarily as interesting to me as it was before the War. Then after the War, it's fantastic again. He does this really biting story about a cartoonist named Tik Tok. It's basically after Joseph Patterson at the

New York Daily News died, and it's really ramming it at his bosses. Some strips have low periods. Can you imagine trying to create work over a 40-year period and have every month...? It's not going to happen. [Spurgeon laughs] It's not! I mean, I don't care... but Chester Gould and Harold Gray really have strong periods almost all the way through their strips. I know with Gould some people don't like -- well, hate -- the Moon Maid stuff, but that's what I read as a kid. I read that in the early '60s in the New York Daily News and it was fascinating. If I had started reading Dick Tracy in the early 30s I probably would have been horrified. [Spurgeon laughs] But to me, it's a fascinating period. That period also his art is so iconographic, it's fantastic.

SPURGEON: How much of working with these strips continues to be an education for you? Is there a strip you've come around on maybe in the last few years, that you didn't like as much before?

MULLANEY: Gasoline Alley I've always liked. I read Dick Moores' version when I was a kid. I appreciated Frank King's work, especially the Sundays, which was basically what was available for us to see. It wasn't until Drawn and Quarterly's editions that I got see what a masterful, incredible storyteller he was. I just think so much more of him now. Twenty years ago you would have asked people to name the 10 or 12 top cartoonist of all time, Frank King would not be on most people's lists, but I think he would be now.

SPURGEON: One way to look at the work you do that maybe doesn't always get taken into consideration is as biography, or as a benefit to biography. There's a real focus on curating the supporting materials, and presenting even within a strip reprint a portrait of the person and their times. I don't know if there's an angle there for a question even, Dean, but I wonder if that was a priority for you...

MULLANEY: It was absolutely a priority for me and for Bruce Canwell when were planning the line at the beginning. That was... we didn't want to just reprint the strips. We wanted to place them in context for a modern audience. Without placing the strips in context, it's... I'm not sure how to say this. It make the reading experience easier. It allows you to get right into the strip. If we can present an introduction that brings you up to speed. If it gives you background on the cartoonist, background on the era, and what the strip is about, then you can start and start enjoying it. The people that read it at the time understood the context. It was 1935 and they were living in 1935. They know what society is like. They know what's going on in the world around them. A person now doesn't necessarily know what it was like living in 1935. So it's our responsibility to provide that context.

SPURGEON: Is there a benefit to just feeling like we know the cartoonist, Dean? That's something we do now, and I think at the very least by virtue of the celebrity that many of them had was a part of the reading experience back then. You knew these cartoonists by default, almost, and knew that this work was the extension of that person. Seeing the man behind the strips... I know I feel I'm relating to Charles Schulz when I read his strips, that I'm relating not just to the strip but to this person.

MULLANEY:

MULLANEY: Absolutely. You're dead on with that. Getting to know the cartoonist and their background, and if they have political beliefs or a social issue they want to get across. That doesn't influence everybody's work, but it influences most of their work. Some more overtly than others. If you look at Chester Gould, for instance, people always talk about Harold Gray being an arch-conservative, but Chester Gould outflanks him easily. Here's a guy that was so upset by what he felt was the liberalization of society, the Miranda decision and things like that in the '60s, that he has to take Dick Tracy off of the planet because he can't figure out how a guy do law and order in this country given that things have become so liberal. He has to take him off the freaking planet. [laughter] That's the background to the story. You can still enjoy the stories without the background, but it gives you more to grab onto. Another level on which to enjoy them.

SPURGEON: You finish up your Alex Toth trilogy next year, right?

MULLANEY: Bruce just turned in his manuscript for the third and final book. I have all the art assembled. Now comes what for me is the fun part of it, which is to lay the whole book out. It should be 300-350 pages of Toth art; we have so much fantastic stuff.

SPURGEON: Am I right in thinking that went from two to three books?

MULLANEY: [laughs] It went from one... it started off as one book, then it became two books, and we kept finding so much material. Fans have been so generous in loaning things. Like I said before, you don't get a second chance at these things. I'm going to be 60 years old next year. I don't know how many years have left, or how many any of us have left. I want to do as many books as I can, while I still can.

SPURGEON: With Toth, I wonder if there aren't some intriguing contexts specific to him. One is that within cartooning circles Toth is so universally admired that I wonder if that wasn't oppressive in some ways, if that kept you from developing a critical view of elements of his work. I also wonder if the fact that he is not known for specific works had an effect in terms of how you approach him. We point to Toth more generally as an artist than to a half dozen significant works in which he played a creative part... even those works we do point to we usually do so as representative

works rather than as formidable, stand-alone, achievement in comics. We might even point to whole periods of his work, or changes in his general approach more than discrete assignments.

MULLANEY: I don't know who it was, but I read someone recently that said, "Alex Toth is the master without a masterpiece." It could be argued that

Bravo For Adventure was his masterpiece, but while it's a good story, a fun story, I don't think the writing is up to the same level as the art in that book.

SPURGEON: So how cognizant are you when you present a book like these Toth books? Because it seems to me that a book series like this one was a good solution on how to present Toth -- maybe the only way to present him -- as respectfully as possible.

MULLANEY: The thing that's interesting, is the fact that he's a master without a masterpiece, that he couldn't write by his own admission, that he was constantly changing stories from writers -- that's the story. The story is the guy's artwork is absolutely incredible. His sense of design. He brought modernity to post-War comics in a way that no one else in comic books did, in a way that Alex Raymond did with Rip Kirby. Toth did this in comic books in a different way, totally above everyone else. Nobody was doing anything close. He influenced everybody working in the medium in the early 1950s.

The other question is why he didn't work on a series for a long time, why didn't he create something, a story, that he could keep doing over and over again. It's because he wasn't able to. That's part of the story. Part of the story is his personality: being friends with someone for 30 years and then deciding one day that because he pissed him off for whatever reason he's never talking to this person again. I remember years ago Julie Schwartz said to me, "You know, an artist can be three things. They can be a great artist, always on time, or a hell of a nice guy. All they need is two out of the three to get work." [laughter] I never forgot that. Alex always had trouble. He had trouble with the editors. He had trouble with the writers.

SPURGEON: He had a strong sense of self. Do you have any idea what he might object to in your books?

SPURGEON: He had a strong sense of self. Do you have any idea what he might object to in your books?

MULLANEY: You never know depending on what day it would be. [Spurgeon laugh] I mean, seriously. I'm not putting him down. The main reason I wanted to do these books is I got to know Alex. I worked with him on the

Zorro books and I admired the hell out of him. He's one of my great artistic heroes. As a person, I think his children say it best in the book. He was a difficult person. That doesn't take away from his art. Whatever was torturing him internally affected how much work he did and the kind of work he did, obviously. That again is part of the story.

SPURGEON: You mentioned turning 60. I think of you as part of the generation as people that rewrote the North American comic book industry. That came up with a bunch of new models for doing business, and expanding what could be published and how, and expanded the breadth of themes that could be engaged. Do you have a sense of your generation's accomplishments? This is a year we lost Kim Thompson, a friend of yours and a prominent member of that generation. Do you have a sense of the graying of your peer group?

MULLANEY: Oh, sure. Kim Thompson's death affected so many of us. Personally, it affected me greatly. Professionally it certainly had an influence. It's made me look at the line and ask, "Can we do more than two books a month? Can we do four books a month?" No one knows how much time we have. If you look at people doing strip reprint books, almost everyone is around the same age, or the same generation at least. Ted Adams at IDW is allowing all this stuff to happen, and he just turned 40. He's younger. But the rest of us. Gary Groth... Charles Pelto... I'm not seeing people 20 years old self-publishing strip reprints. [laughter] They may. But they may say eventually, "What's a newspaper?" I think our generation just like very generation in comics has a profound influence on the medium. Collectively. Some individuals have more of an influence, but I think collectively we all grew up... I think Eclipse started at the same time the Direct Market did. So there were no rules. We were making up the rules as we went along. It was a hell of a lot of fun.

SPURGEON: I mentioned to someone that I was interviewing you, and they mentioned that it struck them that there was a hobbit movie out, and Rocketeer

comics out, and two-three things that reminded him of Eclipse. There is still currency for the kind of publishing you were doing. And of course you guys were a creator-friendly house in a lot of ways, and worked with book distribution, and struggled with earlier forms of many of the same issues that publishers like IDW might now. Are you pretty secure in the legacy from that part of your life? Is there anything that stands out to you now in terms of what you might have been trying to do then? It's 20 years now... and in some ways this whole period of publishing began just as you guys slipped from view.

MULLANEY:

MULLANEY: I'm very proud of everything we accomplished at Eclipse. We published the first graphic novel specifically for the comic-shop market. Phil Seuling was the only distributor, and he looked at me, and he said, "Five dollars for a comic book!? Are you crazy?" So things change. In some respects I was ahead of my time; I did things too soon. We co-published the first line of manga. They sold okay. But manga was just starting to get attention in the US, and it was too soon. That Hobbit book on the other hand, that sold phenomenally. I don't know the sales figures on other books, but we sold a few hundred thousand copies of that one, between the Eclipse edition, the Ballantine Edition an the Harper Collins/Eclipse edition in the UK. The thing sold phenomenally well.

SPURGEON: Ted Adams was an intern of yours, am I right?

MULLANEY: No, he wasn't an intern. I needed an assistant for Beau Smith, our sales manager. I don't know if we advertised in the

Comic Buyer's Guide or

The Comics Reader, but it was somewhere Ted saw the ad. Ted reminded me of this story when he was moderating a tribute to me at San Diego when I got the inkpot. He said it was the most exciting day of his life. He saw the ad, and he called up and I said, "Hey, come on down." He was in Portland, Oregon. He came down for an interview. He drove seven hours -- I don't know how many hours -- down, did the interview, and he went back to the hotel and he was so excited. He said he knew he nailed it. I called him up and said, "The job is yours." I hired him straight out of college. He was never an intern. He was an assistant sales manager to Beau Smith.

SPURGEON: The way that companies are structured now, what they're doing, is there any wistfulness on your part of the opportunities they have now as opposed to what you had back then?

MULLANEY: I have no interest in being in the new comics market in 2013. [laughter] I like to do things my own way. Things are more tightly structured, and more... limited in some ways. More expansive in others. At the beginning of the Direct Market, and with Eclipse, we were writing the rules. Every month we would sit down and figure out what we were going to publish next month. And just do it. There was nobody to stop it. The comic shop market was expanding so retailers were looking for product. They were looking for material. I was in the right place and the right thing. With Ted and IDW now, I can say that Ted is so much more of a better businessman than I was. He's a guy with good taste that likes good comics and wants support them, but he also has good business sense. I would get some money and go, "What cool stuff can we lose $25,000 on?"

*****

*

The Library Of American Comics

*

Mullaney Bio On A Library Of American Comics Page

*****

* one of the Library Of American Comics books

* a Bobby London

Popeye

* book from the LOAC Essentials series

* a Noel Sickles illustration

* a

Scorchy Smith image

* look how busy Milton Caniff's dailies could be in the bottom 1/16th inch

* from

King Aroo

* from

Rip Kirby

* from

The Bungle Family

* Gould's Moon Maid

* a bit of Alex Toth

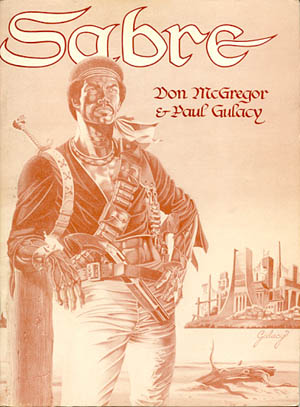

* the

Sabre graphic novel

* Toth (below)

*****

*****

*****

posted 4:00 pm PST |

Permalink

Daily Blog Archives

November 2019

October 2019

September 2019

August 2019

July 2019

Full Archives