December 29, 2009

CR Holiday Interview #9—Jeet Heer On Louis Riel

CR Holiday Interview #9—Jeet Heer On Louis Riel

Jeet Heer

Jeet Heer is the kind of writer about comics I want to be when I grow up: eloquent, forceful and authoritative. Although his writing on comics appears in a variety of outlets, some of the best writing anyone's done this decade on cartooning are Heer's introductions to volumes of classic comic strips like

Walt and Skeezix and

Little Orphan Annie. Heer wrote

a fascinating piece on Chester Brown and Harold Gray when Brown's serial

Louis Riel moved into hardcover form. He was nice enough to discuss Riel further with me here. -- Tom Spurgeon

*****

TOM SPURGEON: In your

TOM SPURGEON: In your National Post

essay about Louis Riel

, Chester Brown and Harold Gray, you noted that Chester had discovered Gray in the early '80s. While there are elements of Gray's work in Brown earlier comics, they become full-blown and much more powerfully obvious in Louis Riel

. Why do you think Brown dove back into Gray to that extent at that point in his career? Was it just appropriate to the subject matter? Had he found something in Gray with which he felt comfortable or empowered?

JEET HEER: It's true that

Louis Riel is much more Gray-like than anything Brown did before. I think there were a number of factors that made a Gray-inflected style a logical choice. Brown's earlier work tended to be personal and inward looking -- the surrealism of

Ed the Happy Clown, the autobiographical focus of

The Playboy and

I Never Liked You, the religious concerns of the gospel adaptations -- culminating with the truly hermetic

Underwater series.

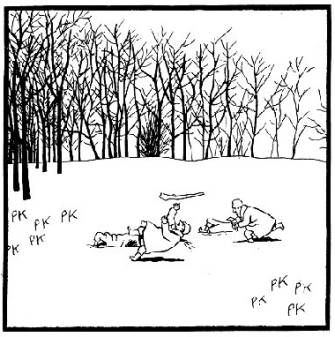

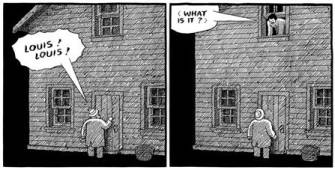

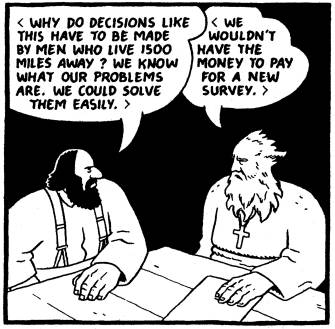

The Riel story, by contrast, was a very public one: based on history, dealing with politics, and often set in public places (open air meetings and courtrooms). Gray was a very public cartoonist in a variety of ways: dealing with public issues, but also showing his characters out in the open with very explicit, theatrical faces. So Gray makes sense for a history strip. Also, although Gray started cartooning in the 1920s, his style with its crosshatching and caricatures echoes the cartooning traditions of the 19th century (especially Victorian book illustrations). Thus it is a style that seems to come from the same world as Louis Riel himself.

SPURGEON:

The most memorable part of that essay for me was when you spoke about how the simplicity of Brown's art work prompted a close reading of the remaining information. That's a fascinating notion, and one that maybe counter to the popular notion that the less information we have the more we imprint our own. Is there something about the way Brown presents the visual information aside from its relative sparseness that captures our interest? What makes him so good at sustaining our interest, do you think?

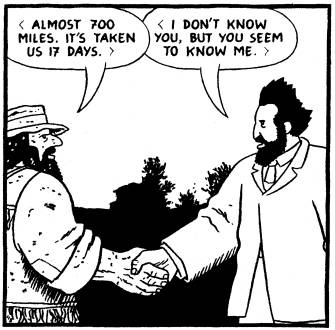

HEER: Aside from the sparseness I mentioned, I think Brown's great strength is in his character design: his people look like their personalities.

John A. Macdonald's slyness and prevarications are embodied in his long Pinocchio nose, Riel's passionate individuality

in his wild hair. Brown is also a master of understatement. One of the big problems with comics is that they are too blunt: melodrama is the default mode of comics. Brown consistently avoids the sort of ham-fisted emotionalism that comics are prone to. Brown's staging is also expert: there is a real clarity to how his people are placed, with the background furnishings also serving a narrative purpose.

SPURGEON: Re-reading

SPURGEON: Re-reading Louis Riel

, one way it really connected to Little Orphan Annie

was the beautiful way each work portrays the outdoors. Something about the way the sky looks, and the wide-open expanses. I know that in your first Little Orphan Annie

book introduction you talk some about the artists that inspired Gray. This may be a stretch, but is Gray's artistic approach suited in a particular way to a story of the central plains? Maybe more generally, how well do you think Louis Riel

depicted that area of the country?

HEER: I'll repeat here a bit from my introduction to the first

Annie book: The geography of rural Illinois left a strong mark on Gray's imagination, as can be seen if he's compared to his Wisconsin-born colleague

Frank King. In King's work, the country-side is always rolling and sloping, with cars constantly sputtering up hills or flowing down valleys. In the early

Little Orphan Annie strips, by contrast, once our heroine leaves the city, the countryside is as flat as a quilt spread out on a bed, each acre of farmland its own perfect square, with stacks of hay and isolated silos the only protrusions on the land. The flatness of the prairies, the prostrate manner in which the horizon spreads out as far as the eye can see, spoke to something deep in Gray's imagination: it perhaps explains his sense of the isolation of human existence, the persistent feeling of loneliness his characters complain of, and their commensurate need to reach out to Annie and create strong (although temporary) families, with the orphan as their child.

Brown of course didn't grow up in the prairies, which are the setting for

Louis Riel. His childhood was spent in the very different landscape of Quebec. But I do think that appropriating Gray's style helped Chester capture the landscape of western Canada, especially the flatness and isolation of the region. I do think there is a tradition of mid-western cartooning, a family tree that is rooted in

John T. McCutcheon and extends to

Clare Briggs, Harold Gray, Frank King (with a crazy branch that includes the grotesque approach of

Chester Gould and

Boody Rodgers). The latest branch of this tree is the alternative comics of

Chris Ware,

Ivan Brunetti, and

Kevin Huizenga. Brown is interesting because he's not from the mid-west at all, in fact is not even an American, but has absorbed the aesthetics of this approach.

SPURGEON: Is it fair to note that

SPURGEON: Is it fair to note that Louis Riel

isn't always historically rigorous? I remember someone pointing out that the story of Riel declining to take his parliamentary seat was different than what Brown portrayed, that Brown's depiction was humorous rather more than it was accurate. Should choices like that change our estimation of the book, or do you think it adds a quality a re-telling that adhered closer to the record perhaps couldn't?

HEER: Well, I think any narrative of the past has an element of fiction to it, whether the author is explicitly doing historical fiction (like

War and Peace) or biography (like

Donald Creighton's biography of John A. Macdonald). I don't see this as a problem because Brown is upfront in his notes about his sources and his narrative choices, which includes the choice to simplify. When you make a narrative you're always selecting from past events and bringing a point of view.

Louis Riel could be classified as a historical novel, but it's about as close to "the facts" as the autobiographical work of

Joe Matt (who also re-arranged events to tell his story). So I don't see this as a problem, but rather as an opportunity to get readers to think more deeply about the nature of historical reconstruction.

SPURGEON: According to Brown, this was the last serial comic of his career, which I think is definitely something that ties into industry and artistic trends of this decade in comics. Did you read

SPURGEON: According to Brown, this was the last serial comic of his career, which I think is definitely something that ties into industry and artistic trends of this decade in comics. Did you read Louis Riel

as a serial, and did that have any effect on how you read it? Do you think being serialized had any effect on the final, collected volume? Do you have any thoughts in general about the decline of serialized print comics? I suppose it shouldn't matter, but that's a way that a lot of us grew to read comics and move back and forth between various authors.

HEER: I bought the

Riel comics in periodical form when they first came out, but perversely didn't read them till the last issue came out so I could do so in one sitting. As art objects, I love all the periodicals Brown has done: he puts such care into the covers and the look and feel. But the periodical form is no longer really a good way to read long extended narratives. There are exceptions: I thought

Speak of the Devil was a dandy serial: I looked forward to each issue. But that's partially because

Gilbert Hernandez works so fast, so the previous cliffhanging ending was fresh when a new issue hit the stands.

In the case of

Louis Riel, I don't think serializing effected the final volume since Brown wrote out everything first.

I'd like to see the periodical form survive but serializing long stories isn't the way to go. What might work is a revival of the early

Eightball model of a series of short stories written in different tones. But it could also be that the form is heading to extinction, partially because its been supplanted not just by graphic novels but also by mini-comics, which is where the action seems to be for those looking for that single-issue kick.

SPURGEON: You've written so well about the positives, but does the general artistic approach used by Gray on Annie

and by Brown in Louis Riel

have a downside? You could argue Riel and Daddy Warbucks are portrayed with a significant amount of remove, that it's hard to understand why people react to them the way another style might make more clear. Is there something that approach doesn't do well, do you think?

HEER: Well, as I said earlier, Brown's earlier work was more introverted, and I don't think that can be done in a Gray-inflected style. It's interesting that although Brown is interested in religion and Riel had a strongly religious personality (seeing himself, as many revolutionary leaders do, in a messianic light), this isn't highlight in the Louis Riel book. But every artistic choice has a drawback as well as strengths.

SPURGEON: With a few years' perspective, where do you think Brown's

SPURGEON: With a few years' perspective, where do you think Brown's Louis Riel

fits into the context of other popular or historical portraits of Riel? In Canada, is it generally well regarded as history, as an artistic endeavor, an as item of popular culture...? How do you feel that it ranks in terms of the great comics that came out this decade?

HEER: It's hard to understate the impact of

Louis Riel in Canada: its one of the best-selling graphic novels in Canadian history (if not the bestselling). It's sort of had the same impact in Canada that

Jimmy Corrigan had in America: it made the graphic novel form much more prominent and respectable in media circles. One thing non-Canadians might not realize is the importance of Riel in Canadian history. He is as central a figure in our national mythology as Abraham Lincoln is in American culture. So the existence of a long, serious graphic novel about Riel has really resonated with many Canadian readers who don't normally pick up graphic novels.

I think

Louis Riel is definitely one of the top 10 graphic novels of the last decade but, as so often with Brown's work, it's an odd man out. The major movement in comics has been towards serious fiction with a heavy emphasis on color and page design (

Jimmy Corrigan,

George Sprott,

Asterios Polyp). But

Louis Riel is a work of history (albeit historical fiction), done in black and white with a simple grid pattern. As someone once said, Brown really does like to go off in his own direction, charting a path that is unique. In that sense,

Louis Riel is very an outgrowth of Brown's own personality.

*****

*

Louis Riel, Chester Brown, softcover, 280 pages, 9781894937894, 2006, $17.95.

*****

This year's CR Holiday Interview Series features some of the best writers about comics talking about emblematic -- by which we mean favorite, representative or just plain great -- books from the ten-year period 2000-2009. The writer provides a short list of books, comics or series they believe qualify; I pick one from their list that sounds interesting to me and we talk about it. It's been a long, rough and fascinating decade. Our hope is that this series will entertain from interview to interview but also remind all of us what a remarkable time it has been and continues to be for comics as an art form. We wish you the happiest of holidays no matter how you worship or choose not to. Thank you so much for reading

The Comics Reporter.

*

CR Holiday Interview One: Sean T. Collins On Blankets

*

CR Holiday Interview Two: Frank Santoro On Multiforce

*

CR Holiday Interview Three: Bart Beaty On Persepolis

*

CR Holiday Interview Four: Kristy Valenti On So Many Splendid Sundays

*

CR Holiday Interview Five: Shaenon Garrity On Achewood

*

CR Holiday Interview Six: Christopher Allen On Powers

*

CR Holiday Interview Seven: David P. Welsh On MW

*

CR Holiday Interview Eight: Robert Clough On ACME Novelty Library #19

*****

*****

*****

posted 2:00 am PST |

Permalink

Daily Blog Archives

November 2019

October 2019

September 2019

August 2019

July 2019

Full Archives