February 17, 2008

CR Sunday Interview: Douglas Wolk

CR Sunday Interview: Douglas Wolk

*****

Douglas Wolk

Douglas Wolk is easily one of the most influential and widely read writers about comics working in North America, with a client list to die for and an attentive audience to match. Among his great strengths is an ability to write equally effectively about art comics and the latest offerings from the mainstream superhero comic book companies. He has also maintained a profile in both older media, such as daily newspaper and alt-weekly magazines, and newer, at the group blog

Savage Critics and his focused, single-series blog

52 Pickup. Wolk's 2007 book

Reading Comics brought to print a mix of general comics theory and specific comics/cartoonist reviews, hitting the difficult mark of proselytizing on behalf of the art form while maintaining a stance that comics is at a point where its great art should justify itself. The book was very well-received, I think initially for the achievement and cultural advancement signified by its existence. The content of Wolk's essay by essay snapshots of various comics and their creators will be discussed for years to come, and hopefully this interview contributes to that process. -- Tom Spurgeon

*****

TOM SPURGEON: I know that you worked in a comic shop... is there anything about that experience that still informs your present-day interaction with comics?

DOUGLAS WOLK: For one thing, it meant I had virtually unlimited access to old and new comics for a few years (and whatever I didn't read there, I read at

Michigan State University's library -- the folks in their Special Collections department were very, very kind to a young, obsessive reader). But I think what I liked best about it was getting to see people's deep attachment to and joy in comics as a medium. Like most comics stores, we had a lot of regular customers, and the day they got to go in and buy the new arrivals -- it was Friday back then -- was a happy day for them. I still get at least a little excited about Wednesdays now.

SPURGEON: How did you go from the comic shop to writing about comics?

WOLK: There was a gap of a few years in there. I moved to New York at the beginning of 1992 and drifted, almost accidentally, into writing (mostly about music) and editing; in 1993, I became the managing editor of

CMJ New Music Monthly, which had a tiny freelance budget and a lot of pages to fill, so I started writing short comics reviews every month. That led to a gig writing longer features about cartoonists for a glossy Australian art magazine called

World Art, then (after I quit the magazine in 1997 to go freelance) to other opportunities.

SPURGEON: I first became aware of you in the late '90s through a couple of your pieces on comics in I think the Village Voice

. What was it like being a writer about comics in that era? How was it different than it is now?

WOLK: Writing about comics was a bit more of a hard sell then, although it was easier at the

Voice than other places. (Alternative weeklies always need content, and if you can put together a decent paragraph and are willing to work for very little money, it's not hard to write for them.) There was usually the sense that you had to make a case for why a general-interest publication's readers would be interested in comics in general, let alone the specific thing you wanted to write about. It's gotten a lot easier over the last decade, though -- partly because there's more good stuff to write about, and partly because there are some editors who've opened up space for comics coverage. A number of publishers have mentioned that Calvin Reid getting

Publishers Weekly to expand its graphic novel coverage was a big push toward the cascade of bookstore shelf space, public demand and publishing acquisition budgets we've seen since 2000 or so, all of which makes it easier to write about comics in mainstream publications.

SPURGEON: Can you talk about the impetus to put together a book of critical writing about comics? Why Da Capo? Were you approached or did you approach them?

WOLK:

WOLK: The idea of putting together a book of comics criticism came out of discussions with my literary agent, Sarah Lazin. She knew me mostly through things I'd written about music (and she works with a lot of other music writers), but she was interested in this idea. I assembled a proposal, and she shopped it around. I'd actually worked with Da Capo once before, when I edited the first volume of their

Best Music Writing series back in 1999, and they'd never really done a book on comics before, but they've been very helpful every step of the way.

SPURGEON: What led you to the structure you used with Reading Comics

? Were there inspirations you were looking at? Because you were going to use some past material, did that dictate the tone or did you have an idea of how you wanted the book to read going in?

WOLK: The structure of the book -- general essays first, reviews of particular books later -- was modeled on a few books by critics I like:

Pauline Kael,

Roger Ebert,

John Updike. A lot of them seemed to group together longish reviews that had been written over the span of a few years, and also group together pieces that deal with broader ideas. The tone mutated through rewriting and tinkering as the project went along -- I was aiming for a

Susan Sontag-ish epigrammatic-academic sort of voice at first, but I couldn't pull it off, and if it seemed unnatural and dull to me, I couldn't very well inflict it on anyone else. So I ended up going back to the kind of casual voice I use for

Salon pieces, since I was going to be using a bunch of them anyway.

SPURGEON: Am I right in thinking that all of the essay on individual works and creators had a previous life elsewhere? If there were new ones, which ones were they and how did you select them? Was there any piece that re-written? Can you talk about your process in going over the essays to be re-used?

WOLK: The Gilbert Hernandez, [Craig] Thompson/[James] Kochalka and

Tomb of Dracula chapters were entirely new -- they were all things I wanted to write about and hadn't really gotten to before -- and some of the other essays have only a few sentences or paragraphs left over from older pieces. (I think the Chester Brown chapter, for instance, cannibalizes a 250-word

Village Voice review but is otherwise new.) The Grant Morrison chapter actually began its life as an academic paper about

The Invisibles, although it was very heavily rewritten for the book. I think at the beginning of the project I made a list of about 40 possible essays for that section, and ended up picking 18 that I was eager to tackle or that would be easy to adapt from available material. When I realized that I could specifically not try to be comprehensive or definitive -- that I could write about what I wanted to write about right then instead of worrying about "completeness" -- that really freed me up.

SPURGEON: In

SPURGEON: In Reading Comics

, you kind of push the discussion of superhero comics into an area that you find valuable -- superhero comics marked by interconnected, shared worlds. That being said, I'd like to know what you think of the success of writers like Kurt Busiek and Robert Kirkman, who have created works that don't have this shared history on which to draw. Is it that they've been able to approximate that feeling in their comics? Does their work operate differently than things like Civil War

or even Seven Soldiers

?

WOLK: Well, they do and they don't have that shared history: both Kirkman's

Invincible and Busiek's

Astro City are very much commentary on the conventions of

Marvel and

DC continuity, and both operate in ways that mean they don't have to deal directly with that continuity.

Invincible specifically evokes '70s-'80s Marvel, to the point of having its own

Official Handbook, and I can't read

Astro City without thinking "Oh, Samaritan, he's the Superman type." But

Civil War and

Seven Soldiers provide particular perspectives on a bigger picture; with

Astro City, you're getting the only perspective on an implied bigger picture, if that makes sense.

SPURGEON: Your chapter on emerging seemed to me more about categorization than discussing anyone's work. Could you identify maybe one or two cartoonists younger than 35 whose work specifically interests you? Or maybe one or two books from younger cartoonists that you think are really valuable. You touch on it lightly at the beginning of the chapter, but do you think the way these artists are coming up, for instance without the market opportunity for many of them to do one-cartoonist serial comics, is going to have an effect on how their work develops?

SPURGEON: Your chapter on emerging seemed to me more about categorization than discussing anyone's work. Could you identify maybe one or two cartoonists younger than 35 whose work specifically interests you? Or maybe one or two books from younger cartoonists that you think are really valuable. You touch on it lightly at the beginning of the chapter, but do you think the way these artists are coming up, for instance without the market opportunity for many of them to do one-cartoonist serial comics, is going to have an effect on how their work develops?

WOLK: As far as younger cartoonists go, besides

Kevin Huizenga and

Hope Larson, who got their own chapters in the book (both practically unaltered from their Salon incarnations!), and

Bryan Lee O'Malley, who's not exactly a big secret... I follow

Laura Park's Flickr page, and I'd love to see her do more narrative stuff, but I'll happily look at anything she draws.

Tom Neely's The Blot makes me eager to see what he's going to do next. (Also:

Anders Nilsen's 35, I think, but a couple people have mentioned that I seemed to be dismissive about his work, and I'm sorry to have given that impression--I love a lot of his stuff, and even when I don't I'm impressed with how hard he's pushing himself.) Yes, I think the market conditions for non-mainstream serial comics are making a lot harder for some kinds of young cartoonists to develop their voice across a substantial body of work -- I can't see something like

Neat Stuff or

Lloyd Llewellyn flying now, for instance. On the other hand, when people really, really need to make comics, sometimes it happens even without decent market conditions, which is why

The Blot exists.

SPURGEON: Any chance for a paperback? Are you happy with how it did? Anything about bringing the book to public you might do differently were you able to do it all over again?

WOLK: There's a paperback edition coming out at the end of June (which will correct some gruesome factual errors I committed in the hardcover). I have no idea how it's sold, and probably won't know until late this year, but Da Capo seems very happy with it, and I'm really happy with the response it's gotten. If I had to do it all again... I'd probably rewrite the entire damn thing, since every time I open it up I see some sentence or argument that I want to tighten. But that's what deadlines are for.

SPURGEON: I know I've kidded you about this, but do you have any idea why you've authored the lightest-feeling hardcover in the history of my reading books? I have socks that weigh more than your book.

WOLK: I think those

Fourth World Omnibus books might be lighter! My guess -- and I could be totally wrong about this -- is that when Da Capo was budgeting for a 110,000-or-so-word book, they didn't take into account that there would be about 100 images (and I had stupidly resisted the idea of including images until fairly late in the process, when some friends convinced me that I was out of my mind). That bumped up the page count considerably, so maybe they went with a less expensive stock? I don't know.

SPURGEON: I apologize in advance for the length of this, but you sent a lot of my flags up in your section on what you call "nostalgia de la boue." For one thing, you call the term "nostalgia market" a former name for comic collecting when it wasn't -- it was a term used for a wide number of activities that included collecting items related to, for instance, old movies and radio programs. For another, when you talk about the tendency of art comics to reference old comics you bring up [Dan] Clowes, [Robert] Crumb, [Chris] Ware and Seth and then make reference to their being a lot of others, which I thought was really loading your point.

SPURGEON: I apologize in advance for the length of this, but you sent a lot of my flags up in your section on what you call "nostalgia de la boue." For one thing, you call the term "nostalgia market" a former name for comic collecting when it wasn't -- it was a term used for a wide number of activities that included collecting items related to, for instance, old movies and radio programs. For another, when you talk about the tendency of art comics to reference old comics you bring up [Dan] Clowes, [Robert] Crumb, [Chris] Ware and Seth and then make reference to their being a lot of others, which I thought was really loading your point.

So let me ask you: can you rattle off 10 or 15 of these supposedly numerous other art comics artists who reference older, feeble comics as significantly (or at least approaching that significance) as the aforementioned? When you say that Crumb hasn't quite let go of MAD

from 50 years ago, can you cite an example where you see this as a detrimental element in a recent work? Considering that MAD

informs all of modern satire, from The Simpsons

to Chappelle's Show

, why shouldn't a satirist have recognizable elements of [Harvey] Kurtzman appear in his work? Isn't this just natural? Why is this a drag?

WOLK: Thanks for the correction on the "nostalgia market" thing. For a list of others who fall into the art-comics-referencing-pulp-comics category, and please note that I love some of these artists' work:

Tim Hensley,

Johnny Ryan,

Ben Jones,

Glenn Head,

Ivan Brunetti,

Onsmith,

R. Sikoryak,

Mark Newgarden,

Kaz,

Rick Altergott,

Archer Prewitt... For a Crumb example -- well, "recent" is relative with him (I confess I haven't read

The Sweeter Side, and I'm looking forward to his Genesis book), but that "Super Duck" story in the third

Mystic Funnies seemed like 2002 Crumb channeling the same strain of

MAD he was channeling in 1968, to no particularly interesting effect. I agree that Kurtzman is always in the air, but influence has degrees --

Chuck Berry informs all of rock, but that doesn't mean I hear "Sweet Little Sixteen" every time I go see a band play.

SPURGEON: I'm a little confused by your summary of the significance of Seven Soldiers

. The idea that these characters in fantastic stories are different ways of describing the human experience and the idea that fantastic stories have their own reality that can imbue our experiences with the fantastic, aren't these concepts that have been around since the first Tarzan

story was published? Is it that he addresses these ideas directly instead of unconsciously that makes Grant Morrison specifically interesting to you?

WOLK: In part, yeah. I think another thing I really like about

Seven Soldiers is the suggestion that it's not just that these stories and characters metaphorically address particular aspects of existence, but that a whole lot of them can systemically form a broader, interconnected web of metaphors for the human experience--the idea that the value of a "shared universe" is greater than the sum of the individual sets of stories that make up that shared universe. Also, it's incredibly entertaining, which counts for a lot.

SPURGEON: I thought one of your better chapters was on

SPURGEON: I thought one of your better chapters was on Tomb of Dracula

, in that you really get at this moral hopelessness that pervades the book and the way that certain artistic choices and publishing factors underlined that element of the work. While I got a bit of a sense as to what effect, I kind of missed out on the why. Do you think the effectiveness was an unintended consequence? An outcome of doing an old-fashioned vampire story? A passing along of nuclear dread or economic despair?

WOLK: I'll optimistically chalk it up to the deliberate consequences of artistic decisions--the fact that the

[Marv] Wolfman/

[Gene] Colan/

[Tom] Palmer team was able to work together long enough and well enough to have a kind of control over the tone of their collaboration that takes a while to develop.

Tomb does take a while to kick in, but it keeps getting more assured (and more morally dark) over time. There's some of that tone that stayed in place for Wolfman and Colan's later

Night Force, although by then it seemed more forced. I don't think

Tomb really had much to say about the '70s, as entertaining as it is now to see some of the outfits people are wearing in it. And yeah, it absolutely got a lot of its power from being a by-the-book vampire story, although there are plenty of those that aren't nearly as good.

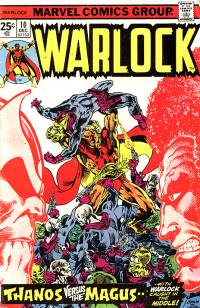

SPURGEON: Reading the

SPURGEON: Reading the Tomb of Dracula

and Warlock

essays in particular, it seems like you avoid talking about them or framing them in terms of influences and factors outside of comics. Ditto Morrison, whose ideas I've always thought of as very much of a time. Is that not a line of inquiry that interests you? Do you think that most comics exist in relation to other comics?

WOLK: It's probably more neglect than avoidance, although I do think

[Jim] Starlin took a few cues from the prose science fiction of the late '60s and early '70s -- there's definitely some

P.K. Dick in there. (Actually, I'd love to read the kind of takes on that material you're suggesting.) I don't know whether I think comics existing in relation to other comics is something I'm interested in or just something that seems nearly tautological: movies exist in relation to other movies, poetry to other poetry, etc. But one thing I was trying to avoid was the habit -- which I know I've occasionally indulged in -- of justifying comics (or implying that I'm justifying them) by tracing their influences from and parallels to art in other media. (I remember, many years ago, reading a terrible book about indie-pop whose thesis was that indie-pop was good because it was inspired by and/or alluded to Modernist art, Beat fiction, etc.)

SPURGEON: Are there any other older comics suites of work that you think are as interesting as the few you include here that you just have yet to write about?

WOLK: Absolutely. ("Suites": I like that!) I've taken a few fruitless stabs at writing about the

[Tom & Mary] Bierbaums/Keith Giffen Five-Year Gap issues of Legion of Super-Heroes; I keep coming back to

Peter Blegvad's The Book of Leviathan; I'd like to go back sometime and take a good close look at the

[Chris] Claremont/[John Byrne] Byrne collaborations in X-Men and Marvel Team-Up and Iron Fist; I don't think I've ever written anything about

Asterix or

Tintin, although I just got an advance copy of

Tintin and the Secret of Literature and suspect it's going to make me want to go back and read all the

Tintin books in order; I'd love to do some kind of long overview of

John Wagner and Alan Grant's Judge Dredd stories;

Jim Woodring is probably my favorite cartoonist but every time I try to write about his

Frank stories they squirm away from me...

SPURGEON: Is there a danger in being a fan of works and then writing about them that you might presume elements that aren't in evidence? For instance, in your Jim Starlin piece you talk about the death of Adam Warlock being shattering, and I couldn't help but feel that we were just supposed to trust you there.

WOLK: Well, where does "admirer" end and "fan" begin? I suppose it's the critic's job to win the reader's trust -- to try to communicate not just our responses to a work but how those responses happen and why, and that's true no matter what the work is. If you as a reader don't buy into what I'm saying, then the problem isn't that one of us is misexperiencing something, it's that I'm not communicating my experience of it well enough.

SPURGEON: Why does manga have such a limited presence in your book? What are your own manga reading habits like?

SPURGEON: Why does manga have such a limited presence in your book? What are your own manga reading habits like?

WOLK: I'm a manga dilettante at best, and figured I should keep silent about what I don't know about. I feel like I haven't really developed a taste for a lot of manga; some of the work championed by people whose tastes are otherwise more or less aligned with mine doesn't do much for me --

Yoshihiro Tatsumi, for instance, leaves me cold. I loved

Death Note, enjoyed the first few volumes of

Monster but haven't kept up, really like a lot of what I've seen of

[Osamu] Tezuka, thought

New Engineering was terrific, etc. But if you'll forgive me yet another music analogy, enjoying a couple of

Mahotella Queens records doesn't make me qualified to write think-pieces about

mbaqanga.

SPURGEON: I think I understand the distinction that you're making when you compare Chris Ware to Charles Schulz and Frank King and George Herriman in terms of what you designated as being impressed by vs. enjoying a work, but I'm not sure what you're getting at when you suggest this keeps Ware from that pantheon. Can you unpack that a bit more for me in terms of the value you place on those gradations of expression?

WOLK: The reason Schulz and King and Herriman are in that particular pantheon is not just their craft and originality but the enjoyment to be had from reading and looking at their work; it makes people happy to read

Peanuts. And it's that particular pantheon -- the masters of a strain of art whose primary purpose is light diversion, as far beyond that as it goes -- that Ware keeps hurling himself against. He defines his work as separated from their work's values every time he mocks the idea of light diversion, which is why a Jimmy Corrigan toy is ironic in a way that a Snoopy toy isn't. Pleasure, fun and joy are tough for me (and for a lot of other people) to deal with critically; a lot of the fine art of the last half-century or so has tried to get away from them, to draw a boundary between itself and uncritical experience of uncomplicated kitsch. But they're really important to me, and one of the things that draws me to criticism is the opportunity to try to puzzle out how they work for me.

SPURGEON: There was a rumor/gripe that was going around at the time of the Reading Comics' publication that you chose a cover that looked like a Chris Ware in order to capitalize on Ware's success, while the book didn't have a particular focus on Ware nor are you a particular booster of Ware. I noticed that none of Ware's eligible books made it onto your

SPURGEON: There was a rumor/gripe that was going around at the time of the Reading Comics' publication that you chose a cover that looked like a Chris Ware in order to capitalize on Ware's success, while the book didn't have a particular focus on Ware nor are you a particular booster of Ware. I noticed that none of Ware's eligible books made it onto your Salon

notable books list. Would you like to speak to that accusation?

WOLK: I actually had next to nothing to do with the cover design of

Reading Comics -- Alex Camlin from Da Capo designed it. (I say "next to nothing" because I did request one small change: the eye on the cover that was initially presented to me looked exactly like the eye on the cover of

Understanding Comics, and I asked if it could please be any other eye... which is why it's looking to the right on copies of the finished book.)

As far as the year-end

Salon list -- I don't think I made it anywhere near clear enough that that was a list of "some stuff I liked a bunch in 2007 that I didn't write about at length elsewhere," not a comprehensive list of my favorite books of the year. If it had been a Top Ten of '07 piece, and more to the point if I'd actually gotten to put it together after 2007 was over, I'd very probably have included

Acme Novelty Datebook, vol. 2 -- but I didn't see a copy of

Datebook 2 until I bought it on December 12, when it came out, and I'd turned my piece in on the 7th (it ran the 17th). And I think I've managed to give a lot of people the false impression that I dislike Ware's stuff; it's probably more correct to say that I'm fascinated but deeply frustrated by it.

SPURGEON: Similarly, was the title selected in similar fashion to put potential readers in mind of Scott McCloud's series of books?

WOLK: No, although I realized almost as soon as I'd thought of it that it had the same structure -- hence my embarrassment over the eye! But I couldn't think of a better title (and discarded some much worse ones).

Reading Comics is also the title of a postcard book published a few months before mine by

Denis Kitchen, who was incredibly kind to not kick my ass about it. He just sent me a copy of a new postcard book he's publishing of political-horror images, with a little note saying "Hope your next book's not going to be called

Capitol Hell!"

SPURGEON: You've stated that you wanted your book to start conversations. Did you succeed? Can you point to some conversations perhaps on-line that were instigated by your book that pleased you? What were they like?

WOLK: I think one of the ones I was happiest about was a conversation that drew some ideas out of the book and applied them to theater--see

this and

this. (And I was also delighted by that "Comics Are Not Literature" panel at

Comic-Con, and the conversation that spilled out into the halls after it.)

SPURGEON: I'm mistrustful of the goal of starting conversations because I think it can be used to absolve the critic's responsibility to say something with clarity and precision and force. Why in your opinion is starting a conversation a goal in and of itself a valuable goal for criticism separate or at least distinct from providing insight into a work? Is there something about the quality of a conversation that a critic starts that is different from the conversation started by the work itself?

WOLK:

WOLK: I don't think the goal of conversation-starting can absolve that responsibility -- a muddled argument is a lot less likely to engender discussion, anyway. ("Honestly, I don't know what I think about

All Star Batman; how about you?" Crickets.) I see a whole lot of arts criticism of all kinds every week, and most of it is totally inert: it doesn't affect what art people choose to experience, or the way they respond to it. If a piece of criticism leads to a conversation, then it's acting in the world, and deepening its readers' engagement with its subject. I also think the value of conversation-provoking criticism is probably greater on the Web than in print: readers of a book or newspaper don't think of themselves as part of that publication's community, but the discourse on a lot of good Web sites is one-to-many-to-many. To put it a different way, "good post kicking off a worthwhile discussion" beats "good post." And conversations started by work itself tend to be small and low-key: it usually takes a reaction stated with clarity, precision and force to get them moving, at which point we might as well call that reaction criticism. I suppose trolling is a sort of guaranteed conversation-starter, too, but I think there's a big difference between phrasing one's actual opinions in a way that's likely to provoke a response and randomly jabbing a pointed stick into a crowd.

SPURGEON: You have one of the on-paper great gigs right now, writing about comics for Salon

's art-interested but perhaps not comics-centric audience. How did that gig start? Are you limited or have you limited yourself to discussing a certain kind of comic there? What has the feedback been like from their regular readers?

WOLK: It started when Hillary Frey, who was then editing

Salon's books section, wrote and asked if I'd be interested about doing a monthly-ish column on comics. It's been a trial-and-error process finding out what

Salon readers care about and don't -- there were a ton of comments when I wrote about

Lost Girls, almost none when I wrote about

Brian Chippendale's Ninja. Generally, if it has to do with history, prose literature, sex and/or politics, that's a good bet for

Salon. I usually run a few possibilities past my editor each month, but if there's something I'm really into I can usually cover it.

SPURGEON: You also write for

SPURGEON: You also write for Savage Critics

. How does that fit into the overall scheme of your writing about comics -- is there a certain kind of comic you can discuss there that you're not discussing elsewhere? How do you feel your work has been received there?

WOLK: I don't even think of it as "work" (much less "my work"), not least because it doesn't pay! Writing for it is something I do to relax, kind of like a plumber getting together with co-workers on the weekend to do a little plumbing; I really enjoy the hanging-out-at-the-comics-store-chatting vibe of the site and its comments. I basically think of

Savage Critic(s) as a place to write about stuff that nobody would pay me to write about -- pamphlet comics, small-press things, oddball items like

Alphabets of Desire. I suppose I could post about them on my own blog, but

SavCrit feels more communitarian, and it's a place that people go to read about

New Avengers or

The Brave and the Bold as opposed to what I'm writing for

Blender or cooking for dinner or the band I saw last night or whatever.

SPURGEON: Without forcing you to rank all of the writers, and with the idea you aren't damning anyone by not mentioning them, are there any writers on Savage Critics to whom you think people should pay particular attention? What is it you like about those writers?

WOLK: I have no idea if

Abhay [Khosla]'s read Richard Meltzer or not, but I get the same kind of feeling from his writing -- he cares as much about making his critical writing interesting and original in itself as he does about the work he's dealing with, and he's hilarious, too. And

Jog's stuff is just a joy to read -- he's curious, enthusiastic, totally engaged, and a brilliant close reader of comics. And he's read everything. I don't know how he does it.

SPURGEON: Now that you've had some time to reflect, what did you learn via your experiment of blogging about the DC superhero series

SPURGEON: Now that you've had some time to reflect, what did you learn via your experiment of blogging about the DC superhero series 52

? Was there anything that was particularly enjoyable about it? Not-so-enjoyable? Surprising?

WOLK: I loved doing the blog -- the regular pace of it, the challenge of coming up with something to say every week, the cover-link-heavy writing style, and especially the community that developed around it. I'd originally decided to do it as a sort of five-finger exercise to make myself write in a way that wasn't constrained by professional obligations, and to contribute something to the comics blogosphere I'd been enjoying a lot more passively, but it was really surprising and gratifying to see how much the people reading the blog were enjoying it and responding to it. It was a little weird to have people introduce me as "the 52 Pickup guy" -- spend all those years trying to build up my professional rep, and end up known for something I do for free! -- but I also got some good gigs out of it, so I'm not complaining.

SPURGEON: Given your insight, why in your opinion hasn't the follow up series from DC enjoyed the same degree of positive reaction as

SPURGEON: Given your insight, why in your opinion hasn't the follow up series from DC enjoyed the same degree of positive reaction as 52

did?

WOLK: It probably has a lot to do with the fact that

Countdown is stone terrible.

52 was a mess a lot of the time, but it was a very interesting mess -- it kept me invested week-to-week in what was going on, it had a lot of really entertaining incidents and characters, it had the heat of collaborative invention and the sense that its creators were trying to make something really fresh and having fun in the process. I look at

Countdown every so often, and I've yet to see anything in it that makes me care about it. (I like

Dirk Deppey's phrase "extruded-comics product.") I was enjoying both

Downcounting and

I Was 28 When I Heard the Countdown Start, but both blogs got so bored with the series they couldn't go on.

SPURGEON: The last couple of years have seen the rise of a lot of woman writers about superheroes, or at least an increased visibility for a critical voice coming from female writers on the basis of the social and cultural implications of superhero comics. Have you read any of these essay or posts? What do you think of them? Are there voices you would still like to see come to the table in terms of those writing about comics?

WOLK: I don't always follow

When Fangirls Attack, but I read

Laura Hudson,

Cheryl Lynn, and a few other bloggers who address women-in-comics stuff; Ragnell's posts on

Seven Soldiers: Shining Knight gave me some particularly useful perspective on that story. (I don't know if it exactly counts as writing-about-superheroes, but I found Pam Noles'

long series of posts on the Golliwogg's appearance in

League of Extraordinary Gentlemen pretty eye-opening too.) Yes, I'd absolutely like to see more voices in comics criticism that don't fit my demographic profile. I'd also like to see more voices in American comics themselves that don't fit my demographic profile. I've been thinking a little about something

Valerie D'Orazio said in your interview with her -- "the question is, who is going to be the female Grant Morrison?" I think the opportunity is there now in a way that it hasn't been as much in the past, and I bet we'll see something along those lines the next few years. But I also don't know if there's a male

Karen Berger or

Francoise Mouly.

SPURGEON: You received some backhanded criticism recently for saying that you were looking forward to Dave Sim's new work from those who believe that his writing on women and politics is repugnant in one way or the other. Do you share these folks' negative assessment of Sim's views in those areas? If so, do you think you can be fairly criticized for still anticipating and enjoying other aspects of his work?

SPURGEON: You received some backhanded criticism recently for saying that you were looking forward to Dave Sim's new work from those who believe that his writing on women and politics is repugnant in one way or the other. Do you share these folks' negative assessment of Sim's views in those areas? If so, do you think you can be fairly criticized for still anticipating and enjoying other aspects of his work?

WOLK: I'd hope it would be clear (and if it's not, it's my fault for being too subtle about it) that my own politics, and especially my sex-and-gender politics, are pretty damn far to the left. But I'm praising the guy's cartooning, not endorsing him for political office. I understand why Sim's politics, and the exhausting way he rattles on about them, would drive people away from his art -- when he writes prose, I scan it for anything he says about cartooning, and otherwise, as Linus said about long words in

The Brothers Karamazov, just "bleep" over it. I also think that to avoid his comics is to miss out on something really special. (

Sean T. Collins compared Sim to Richard Wagner, and not in a good way, but I think he was pretty much on the mark -- when I used "gesamtkunstwerk" to describe

Cerebus, I meant it as a compliment with a little bit of a backhand.) If I had to limit myself to art by people whose world-views matched mine, I wouldn't have a lot left, and if I couldn't enjoy art by people whose world-views I find repugnant, I'd lose some things that mean a lot to me.

SPURGEON: I was intrigued by a recent article in

SPURGEON: I was intrigued by a recent article in Washington Post

about archiving strips, where you wrote, "The next wave of first-rate comic strips may be less likely to come from newspaper funny pages -- where they're thumbnail-sized and crowded by the persistence of ancient franchises -- than from the Internet." You cited Little Dee

, which is a nice strip but I can't quite see it standing alongside work like Gasoline Alley

and Peanuts

at any future date. Do you really believe Little Dee

is one for the ages, and if not, what on-line strips or what about on-line strips make you believe that they're a breeding ground for future classics?

WOLK: I don't know if

Little Dee is for the ages, but I enjoy it a lot, and figured the

Post's readers probably would, too. And I think Chris Baldwin is a good example of someone really talented who's using webcomics as a kind of R&D tool (

Little Dee is very very different from his

Bruno, for instance) -- I wouldn't be at all surprised if he did come up with some kind of lightning bolt in a few years. (

Bobby Make-Believe had to come before

Gasoline Alley,

Li'l Folks had to come before

Peanuts...) What I think makes on-line strips a potential breeding ground is that right now they're a playground: cartoonists have space to romp around and stretch in ways that are nearly impossible within the physical and conceptual confines of newspapers. There's no way

Achewood could fly as a daily newspaper strip, but it's way funnier and more inventive than virtually anything that is in papers right now.

SPURGEON: What's next for you, Douglas?

WOLK: I'm figuring that out now. Most of my income actually comes from writing about stuff other than comics -- I just wrote a cover story for

Billboard about

Starbucks, and I'm spending most of February writing a short history of new wave for a nonprofit organization that's developing a pop-music-history curriculum for schools, and putting together a lecture about the political history of "

The Ballad of the Green Berets." I've got a handful of book possibilities in the hopper, mostly not comics-related (and not called

Capitol Hell), but I'm also trying to work out some ways of writing about comics for a general audience that aren't just, "Here's a new graphic novel! it has pictures! isn't that cool?"

SPURGEON: Finally: what's the last good comic you read? What's the last potentially great one?

SPURGEON: Finally: what's the last good comic you read? What's the last potentially great one?

WOLK: The last good one? I really enjoyed

Kate Williamson's At A Crossroads, which I think comes out in a few months -- it's a diary of a couple of years she spent living at her parents' place while she worked on her first book, and she pulls off the John Cagean trick of staring at boring things so intently that they become interesting again. Potentially great? I love

Eric Shanower's Age of Bronze, even though I don't find myself paying much attention to the individual issues -- it takes a while to get into every time -- but that new collection is fantastic.

*****

* cover to

Reading Comics

* photo of Wolk by Tom Spurgeon

* Wolk's previous Da Capo book

* image from one of Kurt Busiek's Astro City series

* Laura Park

* from R. Crumb

* Marvel's

Tomb of Dracula

* Marvel's

Warlock

* from

Death Note

* a Jimmy Corrigan doll

* from DC's

All Star Batman and Robin

* from DC's

Brave and the Bold

* from DC's

52

* from DC's

Countdown

* Dave Sim's Cerebus

*

Little Dee

* one of the

Age of Bronze trades

*****

*

Reading Comics, Douglas Wolk, Perseus Publishing, 416 pages, July 2007, 9780306815096 (ISBN13), $22.95

*

52 Pick-Up

*

Lacunae

*

Savage Critic(s)

*****

*****

posted 5:00 am PST |

Permalink

Daily Blog Archives

November 2019

October 2019

September 2019

August 2019

July 2019

Full Archives