January 27, 2013

CR Sunday Interview: Calista Brill

CR Sunday Interview: Calista Brill

Calista Brill is Senior Editor at

First Second Books. Last week she instigated

a small ripple of controversy in art-comics circles for a mini-editorial published at

the First Second web site called "

When To Give Up." When

Gina Gagliano wanted to know if I'd interview Brill for this space, I leapt at the chance. I wanted to talk about that piece she wrote but also explore what it is she does for the publisher in one of the rare, hands-on comics editing positions outside of the mainstream serial comic book companies. I had a really good time conversing with her. I edited what follows a tiny bit for flow. -- Tom Spurgeon

*****

TOM SPURGEON: The first question, and one I have to ask, is why you hate young cartoonists.

CALISTA BRILL: Oh, because they're just terrible people. Their wills deserve to be crushed.

SPURGEON: [laughs] You guys have been writing more aggressively just kind of in general on the site, haven't you? Or it seems like you have. On various publishing issues.

BRILL: Yeah. That is correct. We've been on sort of a groove on the blog. Gina, our marketing person, has been sort of heading up that front. The rest of us have been chiming in here and there.

SPURGEON: Do you know if there was a reason for that? Was it just you guys wanted to enhance and increase your presence on-line?

BRILL: You'd have to ask Gina that question because it was sort of her initiative to start with. I can tell you why I like it. Having worked in conventional book publishing for most of my career, and First Second in certain respects fits into that category, I'm very aware of how opaque and sort of mysterious the New York City and Boston and San Francisco publishing scene must seem to people that are outside of it. It's easy to get myopic when you work in this industry, because you're surrounded by it all the time. When I speak to authors and artists and students who don't know a lot about it, I'm often shocked by sort of how mysterious it seems to them. That doesn't seem productive or useful. For anyone, really. Us including. Part of what I like about

this blog series we've been doing is it's out there to demystify the process a little bit, to make things a little more transparent.

SPURGEON: When you say it makes things easier, do you mean that people come to you with misapprehensions that you then kind of have to pave over?

BRILL: Oh, yeah. We're very interested in signing up new talent and fostering new talent and encouraging people. That's very hard to do if people are coming to us with all sorts of misapprehensions -- some of which are flattering, but mostly not-flattering. So it's nice to be able to have a public venue to lay out some of the realities of our business.

SPURGEON: So this essay in particular... As I recall and as I think you posted on top of it, you have been writing them in response to things you've been hearing from people. Do you know what initiated this specific piece? What were you hearing from people that made you want to talk about this? Did someone ask blatantly how do I be this self-analytical or was it something more obtuse that you then put into this form?

BRILL: I suppose it was a combination. I speak to art students frequently, and am invited to sit on classes or attend professional days at various art schools. In those contexts, when you're talking to young people that are investing a lot of time and money into getting started on a career in comics, the economic question comes up a lot. It's something that people are eager to talk about. So it's something that I've talked about frequently. Nothing in this little piece that I wrote on our blog is a departure from what I might normally say in a classroom.

More specifically, it was prompted by a series of... every now and then these pieces make the rounds on the Internet that basically say, "Stick to your dreams. Don't let assholes tell you to give up. You're the best judge of your own potential." This is actually something I agree with. [laughs] I'd like to make that clear. [laughter] I am, however, kind of a contrarian personality sometimes.

Faith Erin Hicks, who I'm very fond of and admire a great deal, and am a huge fan of, posted

this really inspiring and lovely essay along those lines. Because I have this contrarian streak, it got me thinking, after I had wiped away tears from my face from having been so moved by what she wrote, it got me thinking, "What are the circumstances under which hearing from a publisher or another industry professional, 'Listen, just get out of the business' would be useful?"

Where I sort of landed is that it's probably only useful under this very specific set of circumstances, which is the circumstances that I'm talking about in this blog piece, which is if you are setting out and your intention is to support yourself by making comics, then there's a number of things you have to take into account when making that decision. One of them is what industry professionals are telling you about your chances. One factor out of ten. It's up to you how you weigh it and up to you whether you give it any weight at all.

SPURGEON: Why do you think there's a lack of dialogue about those issues? Is it just that to keep doing art, people have to have a kind of willful self-identity? Is it that the publishing industry may gain from having people throw themselves after that career? Why do you think we don't have a more rational discourse on those careerist elements?

SPURGEON: Why do you think there's a lack of dialogue about those issues? Is it just that to keep doing art, people have to have a kind of willful self-identity? Is it that the publishing industry may gain from having people throw themselves after that career? Why do you think we don't have a more rational discourse on those careerist elements?

BRILL: I don't know. Obviously there's been a lot of conversation about this topic over the last few days. Some of it has been sort of painful. I think probably it's a net win, just because personally I think it's something people ought to talk about. Now there's a lot of people out there who have been unhappy with this piece because from their point of view comics is not something you do for money. And art is not a commercial endeavor. That's fine. I have no quarrel with that. The piece that I wrote was directly addressing decisions you have to make when comics is something you do for money. Or if it's something you'd like to do for money.

I think it's a painful conversation for a lot of people. That's probably something that I'm less conscious of than I should be because the part of the comics world that I occupy on a daily basis is a business. We're a business primarily driven by our love of the form, and our passion for beautiful comics, but we're answerable to our bottom line. Conversely, a big part of what First Second is about, one of our loftiest goals, is we would like to create an environment where people can support themselves with comics. We don't succeed always, but it's something we try for. It's a conversation we have with our cartoonists when they're interested in having it, which is not always. I'm always happy to have it when it comes up.

SPURGEON: I was interested in the timing of it. I think you guys are in a place, and talking to Mark [Siegel] a month or so ago I got his sense that he was thinking about those issues, that he was putting together a stable of creators and reusing people and one of the goals of that might be to help people establish themselves in a commercial way as well as an artistic way. The industry is different now. You've been around a while. You must have seen how the way the book publishing industry approaches comics has changed significantly in just the last few years. The nature of the dialogue you're talking about has to be different because of that. I think these are issues people are thinking about in a different way. Do you think it's a different time now when people think of these issues than even three or four years ago when it seemed possible some combination of movies and big-publisher interest would drive a lot more careers?

BRILL: I don't know. That's a good question and I wish I had a better answer for it. I hadn't thought about it. Probably. But I'd have to think more to come up with something useful to say.

SPURGEON: I read an interview with you where you talked about when people find out what you do for a living they invariably say, after being astonished that such a job exists [Brill laughs], "What does that entail?" I'm kind of interested in that question: what your daily routine is like. And I'm also interested in the editing of comics. How much of a hands-on, work-with-the-text editor are you given that it's comics?

BRILL: So that's two questions.

SPURGEON: [laughs] Yes. Yes it is.

BRILL: Which one do you want me to answer first?

SPURGEON: Whatever the first one was.

BRILL: The first one was what is my daily routine.

SPURGEON: Yes. Let's start from there.

SPURGEON: Yes. Let's start from there.

BRILL: It's a complete mish-mash. It changes day by day. I can sort of give you the broad strokes of what my job entails. I'll probably forget 50 percent of it. It actually involves a lot. I keep an eye out for interesting talent that I didn't know about before. So I spend a lot of time on

Tumblr and on blogs and other social media sites that are heavily trafficked by the comics community. I attend shows where I'm also looking for new talent. I also talk to my cartoonists that I already have relationships with about new talent. I also keep an eye out for people who are established that I didn't know about before, or who are doing things I'd like to get in on that I think make sense for First Second.

I acquire books, and that process can mean someone comes to me out of the blue and says, "I've written this graphic novel and I think you should publish it" and I read it and I think it's terrific and I say, "Hello, unknown stranger. Let me give you this sum of money and in exchange we will publish your book in partnership together." What more frequently happens is that things come to me by recommendation or from people I already have relationships with.

When I acquire those books, I'm juggling two forces, which I think is the core of the editor's job often, which is the uneasy relationship between commerce and art. I'm thinking, "Do I believe in this book? Do I think it's beautiful and important and fresh and engaging and profound and fun?" And I'm also thinking, "Do I think I can reasonably sell enough copies of this book to make everyone enough money on it that it's worth our time." By everyone I don't mean just First Second, I mean the author of the book as well. That's something I have to balance and consider when I buy a book for First Second.

Every book is different. Sometimes I acquire books and I sort of think, "This isn't a good bet for a commercial hit but I think it's important it be in the world, so I'm willing to take this gamble." Sometimes I acquire a book and I think, "If this doesn't do well I will eat my shoe." I'm often wrong with both of those gambles. [laughter] But every time I do it I get better at it. We publish a fairly eclectic list, but it has a unifying sensibility. That's something I have a sense for as well.

When I acquire a book I'll then work with the author and the artist, both as sort of an

ad hoc art director -- although

Mark Siegel our editorial director does a lot of that work as well and

Colleen Venable our designer does that work as well. And as an editor, both on story development and broad editorial work, then further down the line on more detailed editorial stuff like line editing and copy editing. I spend a lot of my time keeping things on schedule, keeping lines of communication with the authors and artists who are currently developing books for us. We have a lot of books that are currently in development.

I read a lot of comics published by other publishers. I try to keep current. Also, I just like reading comics a lot. [Spurgeon laughs] That's a pleasurable activity for me. I attend a lot of meetings. I have a lot of phone calls. I write about 80 e-mails a day.

It's sort of weasel-herding, I guess, but it's very pleasurable weasel-herding so it's hard to complain about it.

SPURGEON: When you said you think there's a unifying sensibility for the line, how would you describe that sensibility?

BRILL: Oh, I don't know! As soon as I said that, I thought, "He's going to ask me to define this." I would say broadly that as much as we're interested in really beautiful and lively and engaging and satisfying art, we are also interested in narrative. And in stories. So it's finding works that satisfy both of those needs that human beings have. We don't publish collections of strips. I'm trying to think. Every time I make a broad statement like that, there's always something that disproves it. I don't

think we've published any collections of strips. I've certainly considered it in the past, and there are a couple of strips that if I had the chance to I'd publish in a heartbeat. But it's not our bread and butter.

We look for stories that have something to offer on an emotionally satisfying level. That's sort of a vague thing to say, but it's hard to nail it down any further.

SPURGEON: It seems like you're the one there that engages with new talent on a regular basis.

BRILL: We really all do.

SPURGEON: Tom Hart suggested in his recent interview that younger cartoonists aren't as interested in narrative, in story, as they might have been in the '90s. Do you find that there are competing aesthetics out there that maybe don't fit into what you want to do? Is it hard sometimes to see that? Or are there enough people that want to do the comics that you like that you don't think about those that aren't on your wavelength?

BRILL: I think there are a lot of comics out there that are interested in other aspects of art than conventional narrative. A lot of them are comics I really like. Many of them are comics I wouldn't publish for First Second. I don't know that that division exists along generational lines. That's not a sense that I get. But again, what I should have said at the beginning of this interview is that I can speak only from my own admittedly narrow perspective. So that's been my experience. More broadly, I'm not in a position to judge.

SPURGEON: Another follow-up I had: you talked about a couple of books you've had where you maybe didn't have as strong a feeling in terms of its commercial success as you did an affinity for the work itself. I wonder if there's a book that comes to mind that you were particularly invested in? No matter how it ended up doing for you -- maybe it did well, maybe it didn't do as well as expected. Is there one in which you were really invested in that way?

BRILL: [slight pause] That's a tricky question, because the answer is everything I've ever acquired is something I'm deeply invested in. I'm trying to think if there's one in particular that seemed that it was sort of a risky proposition. It's hard to say, because honestly I feel that way about every book I bring on. I have qualms, always, about whether or not it will do well in the marketplace. And I have great love driving me for them, persuading me to make a case for them. I've turned down a couple of books that came to me that I thought were just beautiful and vital and important, because it seemed clear to me that we couldn't do anything with them that would find an audience for them or recoup the investment we put into them. And also the author's investment. The good news is that this happens very infrequently. Part of that I think is because my sensibility and my tastes tend to line up with the broader First Second sensibility. So the books I get the most fired up about are the books that make sense for us to take a risk on.

SPURGEON: One thing I get a sense of when I read some of the stuff you've written is that you are quite taken with comics' essential qualities. You seem to focus those primary things that comics do really well, maybe over a broader sensibility. I even go back to your being a fan of Wendy Pini's work.

SPURGEON: One thing I get a sense of when I read some of the stuff you've written is that you are quite taken with comics' essential qualities. You seem to focus those primary things that comics do really well, maybe over a broader sensibility. I even go back to your being a fan of Wendy Pini's work.

BRILL: Yeah. I love

Elfquest.

SPURGEON: She has a strong sense of pantomime in her work, and her characters are good actors on the page; these are very foundational comics things. Some of the stuff that you've written about what comics does very well, is that something that's continued to interest you as you've developed as an editor, getting what comics does nailed down pretty well and communicating that to your authors?

BRILL: Oh, absolutely. I love this stuff. I wish I were better at it. I have only my own instincts to go off of, and those get better every year. I envy people that have had the chance to sit down and study comics as a scholarly pursuit. That's something I haven't had the opportunity to do, but I'm interested in that kind of thing. I am someone that enjoys reading prose a great deal. I've also been reading comics since I was a little, wee kid. Some of my first favorites after

Uncle Scrooge and

Tubby and things like that were

Elfquest and also books like

Jim Woodring's autobio stuff that he was publishing in the '80s and '90s and

Love and Rockets. My mother and my brother were really plugged into the indy comics scene when I was a little kid. So I was exposed to that from an early age. So I've been thinking about comics for a long time. It just seems natural that if you're going to be publishing comics, and if you're going to be working with people on comics, why would you not then be making sure that they can do everything that a comic can do that nothing else can do?

SPURGEON: Is there an element that you like to focus in on, that you think you're particularly adept at communicating to authors? You've written about comics ability to communicate a narrative density; moment-to-moment storytelling seems like it appeals to you, too. Is there a hobby-horse? Is there something you're known for taking to cartoonists?

BRILL: That's a good question. I don't know. Let me think about it. [pause]

I'm going to say a bunch of stuff now that's probably going to sound really obvious and basic. So forgive me for that if that's the case.

I spend a lot of time working with people on creating a dynamic between the text and the art where the text and the art aren't duplicating each other's work, where the text and the art complicate and complement each other. I also work with a lot of people that are coming into comics, specifically coming into writing comics from other fields, that have written in other genres and haven't written in comics as extensively. And one of the things I see with authors like that is they don't know how much they can depend on the art to assist them in storytelling. They try to get everything done with the words. That's something I find myself doing editorially frequently is to get people to create a harmonious balance and also a complication -- what's that word for the harmonics -- overtones! There you go. A set of overtones that arise out of the integration of the art and the text.

SPURGEON: Now in a practical sense, is that just nudging people to cut stuff?

BRILL: Often. Yeah. I mean, it can be much more complicated than that, but frequently that's what it sort of boils down to.

SPURGEON: You know, that's not such a basic thing. I mean, it used to be what we considered comics basics. It used to be that comics were defined a lot more in terms of their verbal-visual interplay: Bob Harvey's definition of comics as opposed to Scott [McCloud]'s definition of comics, where everything is now visual narrative. So you're old school. You're really old school.

BRILL: [laughs] I guess so. I really don't think of myself in those terms.

SPURGEON: I don't know how many writers you deal with... I looked at your next year and I guess it was Jane [Yolen] and Jim [Ottaviani] that are both writers that aren't drawing their own work. I'm thinking I'm forgetting at least one more.

BRILL: I don't know the number off hand, but about half of our books are author/artist works and about half have separate writers and separate artists.

SPURGEON: Do you treat those projects differently? Is it different, just in practical terms, to have a script to work with as opposed how a cartoonist doing both might work? Or do you try to keep that the same no matter who you're working with?

BRILL: The good and the bad news here -- good news because I think it means these books are treated better, and bad news because it makes my life more complicated -- is whenever I acquire a new project to work on, the first thing I do is sit down with the author and the artist, or the author-artist as the case may be, and I have a pretty long discussion about how the process is going to work. That conversation is predicated on probably 70 percent consideration of how their process usually works and what they're comfortable doing, and maybe 30 percent on what's going to work for me.

I try to be as flexible as I can. I've never had good luck in situations where I walk into a new project and I say, "This is how this is going to work. You have to deliver the following stage of this book as such. And I'm going to do this and that's how it's going to be." It doesn't set a tone for a collaborative, creative relationship, which is destructive already. And it also just doesn't work, practically, because people come to this with all different kinds of processes. When I'm working with someone that's very new I will a little firmer with how I guide them. When I work with someone who's been making comics for 25 years, I'll often say, "Okay, how do you do it? I'm going to be involved; how do you want me involved? At what stage is it useful for you to get comments from me?"

SPURGEON: When you work with, say, George [O'Connor] or with Faith, someone you're working with again, the recurring talent, does that help you as an editor to have those comfortable relationships?

BRILL: It's lovely. Yes. And it's not maybe the main reason we seek out these lasting relationships with people. It's certainly an aspect of it. We know what to expect. They know what to expect. And also, the more frequently you work with someone, the more productive and the deeper the creative relationship can become. The more you trust someone.

SPURGEON: Do you have a wish list at all? Are there people with whom you'd kill to work?

SPURGEON: Do you have a wish list at all? Are there people with whom you'd kill to work?

BRILL: Jaime Hernandez. His work on

Love And Rockets has been one of the most artistic things I've been exposed to in my life. I would love to work with

Jim Woodring. He's another person I've been following with incredible admiration since I was a kid. I like

Emily Carroll an awful lot. I would like to work with her. I mean, there is a wish list. It has like 500 names on it.

SPURGEON: One thing that came up when I talked to Mark at Comic-Con last year -- I got a sense from him that he was happy with where you guys are right now, that things had settled a bit, that First Second had found a comfortable place in a directional sense.

BRILL: I feel the same way.

SPURGEON: So you feel that you've found a good place and it's a lot about executing what you're doing right now, at least for a while?

BRILL: Yeah, that's well-put. I agree with that statement.

SPURGEON: [laughs] From your perspective, how did you guys achieve that? Was it simply finding out what works in the marketplace? Was it about finding the right talent? Was it becoming comfortable yourself in what you're doing? Was it all of those things? What kind of locked that feeling into place?

BRILL: I don't know. I've sort of wondered that myself. It's probably a combination of all of those things. It also helps that we have had a stable crew for a couple of years. The core First Second gang is Mark and me and Colleen our designer and Gina our marketer and our publicist. We know each other very well and we work together very well. We get along great. That's helped a lot, I think.

A lot of projects that we set in motion right at the inception of First Second are also now bearing fruit, which I think has helped.

SPURGEON: What would be an example of that?

BRILL: Oh, let's see... I'm blanking. There were a few books we've published the last couple of years that were in development for many years. They finally appeared.

But beyond that, it's something ephemeral. It's hard to pin down. I will say, I don't want to make it sound like we're smugly resting on our laurels here.

SPURGEON: Well, that's the next question. Do you have a sense of things you'd like to do there three, four, five years from now that you're not doing now?

BRILL: I have a sense of something I'd like to do right now that I'm not doing right now, which is that First Second consciously tries to publish books for readers of varying ages and also varying sensibilities. I personally am a fan of very young, very goofy comics for kids. I also love serious adult literary fiction and non-fiction and everything. We are a little spare on the youngest end of our list, and I would love to bulk that up. I've been keeping an eye out for really fun, goofy, silly, satisfying books for younger readers because that's something I personally enjoy a great deal.

SPURGEON: Is that a market correction? I guess Francoise [Mouly] is doing stuff like that with Toon but there's not a ton of it... or is it just a sensibility issue, that you just want to do that?

BRILL: It's sort of a combination. I wouldn't be pursuing it if it wasn't something I was interested in personally. But I also feel comfortable pursuing it because I feel there's a place for it in the market.

SPURGEON: Is there an ideal work, maybe a past work you think of when you think of what you'd like to do?

SPURGEON: Is there an ideal work, maybe a past work you think of when you think of what you'd like to do?

BRILL: I mean again, I'm exposing how little my tastes have changed since I was 10 years old [Spurgeon laughs]. To me,

Carl Barks and

Don Rosa's work on

Uncle Scrooge is the

ne plus ultra of excellent kids comics. It's a great combination of ridiculous gags and really fun, exciting, strange adventures.

SPURGEON: The narratives are really powerful on those duck comics if you haven't read some of the longer stories in a while. It's like inhaling story.

BRILL: Right!

SPURGEON: They can be pretty amazing that way. I would look forward to seeing you put out something like that for sure. [slight pause] You know, I'm not sure how many questions I have left.

BRILL: There's something we dropped that I'm happy to talk about if you think it would be of interest. It's how one would go about editing a graphic novel.

SPURGEON: I am

interested in that, the practicalities of it.

BRILL: As I said earlier, it does tend to vary on a case by case basis, at least how I approach it. But there are certain things that always happen. I like to be involved in the broad development of the story. I'm interested in working with people on structure and character development and world-building, all of the fundamental aspects of storytelling. It's something I really enjoy doing. It's something that's when the chemistry is right -- and luckily, it often is -- having a collaborative relationship with an editor can improve that process for people. It doesn't always, but it can. That's a satisfying thing to be a part of. I also do some limited art direction work on the books that I work on. I have a decent aesthetic eye. I generally don't sign up artists whose art I don't already love and trust, so I don't tinker too much. But I keep an eye out for the nitpicky things, like awkward body language, unclear visual storytelling -- the practical aspects an editor can be useful on.

Once the art and the text are finished and are in place together, I generally go through the book with a fine-toothed comb, and do an intensive line edit. Depending on the book that can mean I change three pages or it can mean extensive changes on every page. It's much more common that the former is the case than the latter. Once that has happened, the files come in and they go to a designer. Usually our designer Colleen. Occasionally we send them out to freelancers we trust. We have a number of different copy editors we work with, most of whom we have been working with for a long time and who understand comics and know how to read them and how to edit them. The copyedit stage is more the nitty-gritty: checking punctuation, and grammar and clarity. Then I go over all of that myself as an editor and say yes or no or "Hey, author, what do you think?" then send that off to the author. They make their comments and send them back to me. We do several more rounds of that before the book is ultimately ready to go to the printer.

Once it's gone to the printer, I spend a lot of time during this whole process keeping track of budgets and schedules. Once it goes off to the printer I need to worry about that less because it's in the hands of our production department. My reward after it has gone off to print is when a printed book comes back and sits in my hands. That is one of the most satisfying things I experience in my life.

SPURGEON: Is it my impression that you guys do a lot less translated material now? It strikes me that that used to be a greater component of your line.

BRILL: It still is a component of our line. It's something we actively seek out. We do less of it. Partly because we now have a larger stable of domestic authors, people in the US we work with frequently and would like to work with again. We actually have several foreign projects coming up in the next couple of seasons.

SPURGEON: When you said earlier that you guys have a massive amount of stuff in development, how much is massive? How much is floating out there?

BRILL: I can answer that question, but I'm going to have to count. Give me a couple of seconds. I'm going to do a quick back of the envelope. Right now it's nearly February 2013, so not counting this Spring... somewhere in the range of 50 to 75 projects in development. And part of that is that graphic novels take a long time to make. We like to publish -- what are we at now? -- 20 to 25 books a year. That means having a heck of a pipeline.

SPURGEON: Off the top of my head, I remember in the initial announcement of the company a Brian Ralph book.

BRILL: In the pipeline.

SPURGEON: That's still in the pipeline?

BRILL: Yes! It is! I've just seen some of it; it looks amazing.

SPURGEON: [laughs] Are there books that you give up on?

BRILL: It has happened. The good news is that it happens exceedingly infrequently. Our track record... not our track record. There's probably a sports metaphor that would be useful here.

SPURGEON: Your batting average?

BRILL: Our batting average. There you go. Our batting average has been quite good. That's not on us. That's a testament to the excellence of the people we work with.

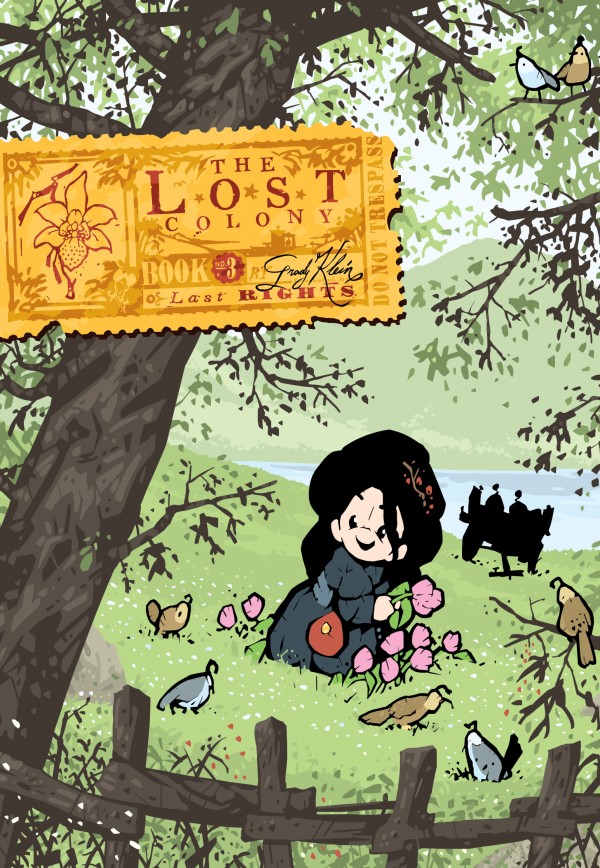

SPURGEON: What about Grady Klein? Are you still doing those books at all? I liked those books.

SPURGEON: What about Grady Klein? Are you still doing those books at all? I liked those books.

BRILL: You mean

The Lost Colony?

SPURGEON: Yeah. They were fun and weird.

BRILL: I love that series. I love that series as well as anything we've published. It is a source of heartache to me that they didn't find a larger audience. Grady's working.

He has a terrific series right now that's non-fiction. It's not from us. It's from a different publisher. I would love to work with him again. That series... it didn't really work commercially in the end. And that's a disappointment because we all love it. We would have loved to have seen it thrive.

SPURGEON: I don't know if this is something you can share, but how do you come to the decision to kind of not do something like that anymore? To drag in another sports metaphor, is there a post-game meeting? Do you assess projects when they're done, look at what worked and what didn't, what the sales are?

BRILL: Here's a terrible insider tip for you. This is more about the publishing industry than the comics industry. I used to work for a different publishing house that was at the Walt Disney company. After every publishing season, there would be a meeting called "the post-mortem" where that conversation happened. Every time I went into that meeting I thought, "Calling this a post-mortem basically makes the tone of it a foregone conclusion."

Yes. The answer is yes. Not in an especially systematic way, we take a look at it and try to make some call about whether or not it was a business success. That is never a conversation that is isolated form "How was it received?" "Did it find fans?" "Did we believe in it?" "Are we glad we published it regardless of how it sold?" It's never an isolated discussion. It is part of what we look at. The fact is, if the first three books of the series haven't sold enough to begin to justify a fourth, then it's very hard to make an argument for the fourth. In certain cases I have tried and failed. In certain cases we have continued a series that we probably should have continued. There's no formula for it. It's a sort of painful and complicated decision that gets made every time on fresh ground.

SPURGEON: There's an art to publishing. And I imagine that this is more an artistic choice than a formula.

BRILL: It's not an algorithm. It is more an art than a science.

SPURGEON: Do you think you're a lifer? Is there a point where you'll know when to give up? Do you have those kind of analytical thoughts about your own career path?

BRILL: Not really. I am a lifer. It's very hard to predict what the future will be. I have no intention of ever doing anything else as long as this is still an option for me.

*****

*

First Second Books

* "

When To Give Up"

*****

* photo of Calista Brill hard at work supplied by Gina Gagliano

* the First Second logo

* Brill at TCAF 2011 (photo by me)

* Wendy Pini's work

* three cartoonists with whom Brill would love to work: Jaime Hernandez, Emily Carroll, Jim Woodring

* a Don Rosa page

* from the series

The Lost Colony by Grady Klein

* one more of Brill at the office from Gagliano; thanks, Gina (below)

*****

*****

*****

posted 5:00 am PST |

Permalink

Daily Blog Archives

November 2019

October 2019

September 2019

August 2019

July 2019

Full Archives