November 16, 2008

CR Sunday Interview: Jesse Reklaw

CR Sunday Interview: Jesse Reklaw

*****

Jesse Reklaw

Jesse Reklaw's

The Night Of Your Life will be seen by most as the latest in Dark Horse's ongoing, informal series of print publications featuring prominent webcomics. As we find out in the interview below, a difference with Reklaw's book is that it had been planned before the series came together and was kind of grandfathered in. That's an appropriate place for the book in the sense that Reklaw's on-line efforts precede most of the strips receiving praise right now by an entire lifetime or two in Internet years. It's worth noting that

Slow Wave, a comic where Reklaw translates into comics form other folks' dreams, straddles both the growing on-line funnies world and the fading one of alt-weekly comics distribution. One hopes that it finds purchase in enough places to allow Reklaw to continue doing it for as long as he likes, and to facilitate the cartoonist's moves into different projects like the memoir

Couch Tag. I caught Reklaw at the far end of of a fairly extensive tour in support of

Night. He seemed very nice. -- Tom Spurgeon

*****

TOM SPURGEON: Am I right in that you left graduate school at Yale to pursue cartooning? I see that mentioned, but always kind of in a way that indicates trivia. How did you move from one career path to the other, and was that difficult? Have you ever thought about returning to school?

JESSE REKLAW: I was in the PhD program at Yale for Computer Science, and it wasn't really working out -- partly because it wasn't the best program for my interests (artificial intelligence), and partly because I was just beginning to realize that I couldn't continue to do both art and computer science at the level I wanted to, so I really had to choose one. Around the same time,

Slow Wave (which I had been self-syndicating for three years) got picked up by five papers in a two-week period, and I calculated that -- in my dumpy grad student apartment, with no car or serious expenses, entertaining myself with free film school movies and dumpster-diving, and basically being a cheap-ass -- I could support myself on comics.

I knew at the time it was very unlikely I'd ever return to grad school, and certainly not at a place like Yale, so it was a pretty tough decision. I think I made the right choice, though if I knew it would take me another ten years to get where I am now...

SPURGEON: Slow Wave

has been around for a long time, almost since the beginning of the wider public perception of the Internet, and I wondered if you could talk about some of the early kind of Internet-culture influences on the strip that I've seen you mention in other interviews. The first is that I think you started doing Slow Wave

during that first period where people were desperately looking for original on-line content, or at least saying they were, am I right? The second is something you mentioned in passing, that the collaborative impulse of the strip comes in part from wanting to engage in the culture of sharing and collaboration that the early Internet boosters supported.

REKLAW: Slow Wave very much came out of that early collaborative/interactive digital art movement, and I certainly wouldn't have been able to do the strip without the internet's easy access to thousands people who would send me dreams. The concept came out of a 24-page dream comic I self-published called

Concave Up, in which I drew more long format dreams. Some of the submissions were too short for anything but 4-panel strips, so I drew those and published them on my website to attract viewers who would hopefully buy the 24-page comics. Few sold, but on a lark I submitted

Slow Wave to some alt weeklies, and had some success there. I still published

Slow Wave online though, and I saw it as part of the internet collaborative art culture. I also made and sold fonts, zines, hand-made stuffed animals, plus had an HTML-chat program and an online diary briefly, all on a site called nonDairy.com, which I envisioned to be a collective of artists (me, my girlfriend at the time, and a few friends). I was inspired by several other such internet art hives, like SITO, which is still around.

SPURGEON: Has any aspect of Internet culture since changed the way you've done the strip? Are there any comics on-line efforts from which you've been tempted to borrow an approach or a way of doing things, either business-wise or creatively?

SPURGEON: Has any aspect of Internet culture since changed the way you've done the strip? Are there any comics on-line efforts from which you've been tempted to borrow an approach or a way of doing things, either business-wise or creatively?

REKLAW: Later people came along who were really able to make a living off their online comics and merchandising. I've tried making T-shirts, prints, postcards, and such, but I don't think

Slow Wave has the kind of fan base that can support a whole web store, and I guess ultimately that's not what I want to do with my comics.

SPURGEON: Should we consider The Night of Your Life

part of Dark Horse's current, wider efforts to do print editions of on-line strip like with The Perry Bible Fellowship: The Trial of Colonel Sweeto and Wondermark: Beards of our Forefathers? Or are you your own thing? I ask because you were talking about a collection as long ago as 2005.

REKLAW: When Dark Horse first made their offer, I understood my book was part of a creator-owned series that would include the works of

Gilbert Hernandez and

Paul Chadwick. But I think as things developed, and the marketing people got involved, it made more sense for Dark Horse to present it as part of a "webcomics in print" series.

The comics in

The Night of Your Life collect strips from 1999-2003; I had been delinquent in finding a publisher for them after my first book (

Dreamtoons, which collects 1995-1998) came out in 2000. I now have enough material for another five-year collection of

Slow Wave, but it'll probably be a few years before that comes out. It contains a lot of style experiments that I'm not sure how to organize.

SPURGEON: What is Dark Horse like as a publishing partner? As the work's already done, do they make suggestions as far as presentation or which strips to use, or are they willing to follow your lead?

REKLAW: Dark Horse (which to me was mostly

Diana Schutz, my editor) was pretty hands-off. They had some small but very helpful edits and production tweaks, but mostly the book was mine to edit and design. It really helped having them in town (Portland, OR) for when problems came up, and that proximity was partly why I wanted to work with them. Also, Diana is fun and a great comics mentor.

SPURGEON: Whose idea was a tour? How has Dark Horse been in terms of support in this endeavor. You're kind of doing it rat-a-tat-tat, one stop after another? What made you want to get out there and hit a bunch of cities?

SPURGEON: Whose idea was a tour? How has Dark Horse been in terms of support in this endeavor. You're kind of doing it rat-a-tat-tat, one stop after another? What made you want to get out there and hit a bunch of cities?

REKLAW: The tour was pretty much all me wanting to get out there and have some fun. My publisher for

Dreamtoons (

Shambhala) organized a tour for me, but it was basically a disaster -- only two dates, one on the east coast and one on the west coast. I got some good tips from

Al Burian at a Portland Zine Symposium workshop a few years ago about booking tours. I wanted to try it, just to see what I could do and get some experience. Selling books was cool too.

SPURGEON: How has the tour been so far?

REKLAW: A whole lot of work and a financial loss, but really fun and addictive too. Part of my strategy was to link up with other people on tour, to share the costs of travel, and the shame of low attendance. I had a great time being in a car with

Trevor Alixopulos,

Ken Dahl,

Hellen Jo, Calvin Wong, and others. I was really drained when I got back from the east coast half, and thought it would be difficult to get excited about the west coast tour, but after a few days I couldn't wait for it to start.

SPURGEON: Jesse, what's the status of your involvement with Global Hobo? This is terrible of me, but I can't tell if you're still hanging in there.

REKLAW: It's no fault of yours; we never got out the press release that

Eli Bishop took over Global Hobo earlier this year. He's doing a terrific job of getting new books up on the web site.

SPURGEON: What have you learned about the business of comics and 'zine culture through Global Hobo? Is there anything that's particularly discouraged or encouraged you about that aspect of cartooning?

SPURGEON: What have you learned about the business of comics and 'zine culture through Global Hobo? Is there anything that's particularly discouraged or encouraged you about that aspect of cartooning?

REKLAW: I really wanted to learn more about distribution, and Global Hobo certainly helped with that. It gives me more sympathy for publishers and what they have to deal with, and also lets me know what to look for in a publisher. Going into Global Hobo I knew it wasn't going to make money, but I couldn't help myself from trying to make it work financially. When, after three years, I finally admitted that the best I could do selling mini-comics was make about $2/hr, I felt kind of stupid for throwing so much time into it. But sometimes it takes me feeling really stupid about something to make a change.

SPURGEON: I think of you as part of a group of cartoonists of a certain age. How important has it been to find friends and creative fellow-travelers as you've developed as a cartoonist? Is there any downside to being part of a creative community like that? What are the positive aspects for you personally?

REKLAW: I've always needed community, and when I lived in Connecticut for five years I was really starved for it. I'd be interested to know who else comprises the group you see me in, because I've been continually frustrated and jealous seeing people my age (and younger!) find success and notoriety in a community. The two people I feel the most affinity with are

David Lasky and

Dylan Williams, because we're all ex-early '90s SF Bay Area cartoonists who never seemed to settle into a community or find great success.

SPURGEON: Something I read made me think that you think of yourself as less of an on-line cartoonist and more of an alt-weekly cartoonist whose work also appears on-line. Is that fair?

REKLAW: I guess I toe the line. Like I mentioned,

Slow Wave couldn't exist without the internet. It's certainly cooler to think you're an alt-weekly cartoonist instead of a web-cartoonist, since there are so many web-cartoonists at an amateur level. Maybe

Slow Wave is more of a print-comic since that's where my money comes from.

SPURGEON: I know that you had at least five clients because you won an award in a five papers or over category. I also know that of your original two clients, the Rocket doesn't exist and the other paper whose name I forget no longer carries it. Lynda Barry painted a brutal picture of the alt-weeklies as a home for comics in an interview I did with her this last summer. What's the state of that market right from your perspective, and what is your place in it?

REKLAW: I have been in about 8-12 papers since 1998, usually dropped from one around the same time I get picked up by another, so my circulation is conserved. There is no security for an alt-weekly cartoonist though. Lately it seems to be getting worse. I send out submissions to new papers once a year or so, and the last two times I've had zero response. Usually I'll get three to five inquiries, and one of them will pick up the strip.

Joey Sayers who does Thingpart said she's had the same experience recently. I don't know if it's the downturn in the economy, or the fact that many alt-weeklies are no longer very alt, since they're being bought up by media conglomerates who like to consolidate content and staff. It might be that I just lucked into an alt-weekly boom in the mid-'90ss, and it's all falling apart now.

SPURGEON: It seems like in the late 1990s there was also a mini-boom of interest in dream narratives in comics, with cartoonists like Rick Veitch and Max doing dream comics or comics that depended on that way of looking at reality. Were you interested in any of these other efforts? Are there dream narratives in other media that interest you?

REKLAW: Julie Doucet was a big inspiration for me doing dream comics. I loved the way she captured small moments of twisted reality, and I wanted to try and do that. I was later (1997 or so?) very inspired by

Jim Woodring's comics. I'm not sure why it took me so long to get to them. I've enjoyed Rick Veitch's work, but it never provided for me a complete world to explore, like Doucet and Woodring did. Did Max do real dream comics, or were they just fiction masquerading as dreams? I'm not so into that, which seems like a false use of fiction. I could never get into

Winsor McCay for the same reason. Most other media seem to use dreams in that false way, though

Akira Kurosawa's Dreams was pretty cool.

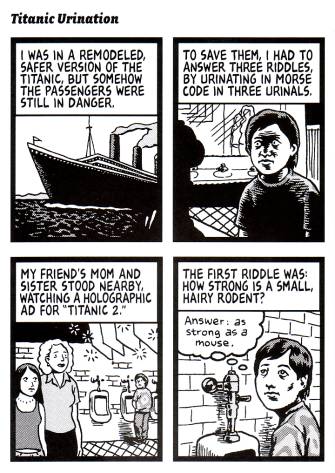

SPURGEON: The Joanna Davidovich "Live Nude Girl" dream made me eyes pop a bit because it's the first time I'd seen you work in fewer than four panels. Since it's clearly not a formatting issue if you could submit that one, can you talk about why you work in that rigid structure? What made you break out of it there, and what does in general?

SPURGEON: The Joanna Davidovich "Live Nude Girl" dream made me eyes pop a bit because it's the first time I'd seen you work in fewer than four panels. Since it's clearly not a formatting issue if you could submit that one, can you talk about why you work in that rigid structure? What made you break out of it there, and what does in general?

REKLAW: I did a few strips in my first book (

Dreamtoons) in three panels too; it's just that some strips don't have enough content to fill four panels. Since

Slow Wave is printed both as a long strip (1x4) and a grid (2x2), I do need to make sure the first half has equal width with the second half. So using a long panel in the top or bottom is my only formatting choice (unless I want to go more than four panels, which I don't, since the narration looks screwy when it gets cut too small like that). I think putting dreams -- which are loopy and tangential -- into a rigid format helps the reader to follow them.

SPURGEON: Are there dreams that are too abstract for you to draw in a way that interests you? Most of your cartoonist have at least a time line aspect to them: this happens, this happens, this happens? do you get dreams from people that are more random or out there?

REKLAW: There's a lot of stuff I don't try to do because it just doesn't interest me, like randomly shifting realities and non sequiturs. But I'm also conscious of trying to tell a story that others will find interesting, and that a large number of people (who aren't necessarily into oneiric minutiae) will be able to follow. So I do clean up a lot of ambiguities. Like if someone says in their dream that a person was a mix of their dad, Christopher Walken, and some guy they saw selling hotdogs in the park, I'll pick which one of those identities best serves the dream narrative.

SPURGEON: How has your work refined itself doing it for so long? Are there strips or things you don't do now that you may have done a long time ago? How much do you consciously work on refining your work?

REKLAW:

REKLAW: For the first 20-30 strips, I was really into oddness in dreams, and tried to honor the weird details. Later I wanted to focus on the humor, because I saw the strip as being more or less a humor strip (though some would disagree). Lately I've just been trying to keep it fresh. When I first started doing this strip 13 years ago I thought I'd never run out of material, but it's surprising how many dreams I get that are similar to ones I've already drawn.

SPURGEON: Your strip has a very striking look. Can you talk about the heavy, dark quality to the line work and overall look of the strip and how you approach it as a cohesive, visual entity? How did you decide on the lettering choices you use?

REKLAW: I try to be conscious of information design principles in my comics, to enhance clarity and flow. But I think I have a tendency to overwork the details, which is bad. The heavy lines may in part be a function of the smaller size I drew the strips collected in

The Night of Your Life -- almost at the size printed. I draw them much bigger now, though I'm thinking of going a little smaller because my draftsmanship gets wonky at that large size. I'm really attracted to early '60s illustration style, realistic but bold and simplified.

As for the lettering, I made a font of my comics writing in 1993 when I was an undergrad at UC Santa Cruz, and I used that for

Slow Wave when I began the strip. The word balloons were hand-lettered because I didn't have an easy way of doing it on the computer back then, and I made them mixed case to differentiate from the narration. Although I'm now a fan of hand lettering I've kept the hybrid look of

Slow Wave for consistency.

SPURGEON: Do you ever think about suspending the strip or bringing it to a close? What might make you do that? Is it helpful to have the occasional outside comics project?

REKLAW: Just about every week (right around deadline time) I think about quitting

Slow Wave, but it's such a great opportunity to try out techniques and get a steady paycheck (well, ten of them), that I'd be a fool to quit unless I had something better lined up (or I just couldn't do quality work anymore). I started drawing other people's dreams because I wanted to work in private on my comics writing. It's taken me a hell of a lot longer than I thought it would, but I'm finally at the point where people can get from my writing what I'm trying to convey.

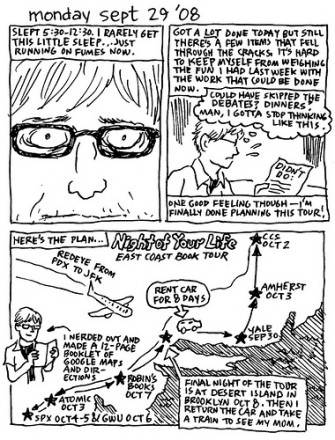

SPURGEON: I forgot to ask directly abou the comics you've been doing lately in conjunction with that publicity tour. Tell me a little bit about the tour diary; is that something you've done before? Why add the work?

REKLAW: I was just feeling kind of manic when I was setting up my tour, and I tried out anything I could think of to get more press; the diary was one of those things. But I have always toyed with the idea of doing a diary comic, and I was looking for some way to use the new social networking sites too (like flickr, facebook, etc.). It's really not that much more work, and if the diary wasn't successful, I would have quit after two or three weeks. But I think I'll do it for a year now and see where I'm at.

SPURGEON: Other than that and the syndicated Slow Wave, do you have something in mind as far as a next project?

REKLAW: Right now I'm working on about seven different long projects, one of which is a memoir called

Couch Tag. A chapter from that was published in the

Best American Comics 2006, and I'll hopefully be done with the whole 150-page book in 2010.

*****

* cover to the new book

* photo by Tom Spurgeon or Gil Roth, I can't remember; probably Gil

* dream from account given by Grig Larson, in the new book

* from the dream diary

* Reklaw's excellent mini-comic

Applicant

* the Live Nude Girl comic described in the interview

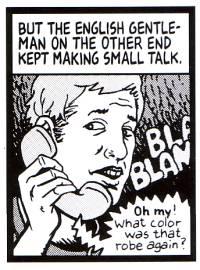

* panel from a dream account given by Colin Atrophy

* panel from a dream account given by Ray Jewel; note the differences in lettering

* (below) the dream to which I most related because it was like one of my own; from an account by Max McBarron

*****

*

The Night Of Your Life, Jesse Reklaw, hardcover, 256 pages, October 2008, 9781595821836, $15.95

*****

*****

*****

posted 7:00 am PST |

Permalink

Daily Blog Archives

November 2019

October 2019

September 2019

August 2019

July 2019

Full Archives