October 19, 2008

CR Sunday Interview: Lucy Knisley

CR Sunday Interview: Lucy Knisley

*****

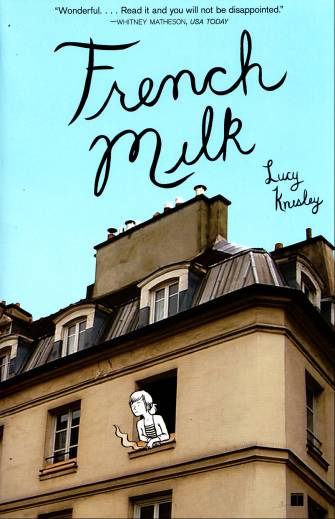

I knew nothing about

Lucy Knisley before we spoke that I hadn't learned from reading her book,

French Milk. I knew that she's in her early twenties, she became a student at the

Center For Cartoon Studies after completing course work at the

School of the Art Institute in Chicago, and she has a book out at an age most of us are still working at jobs instead of launching careers.

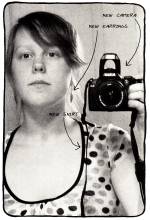

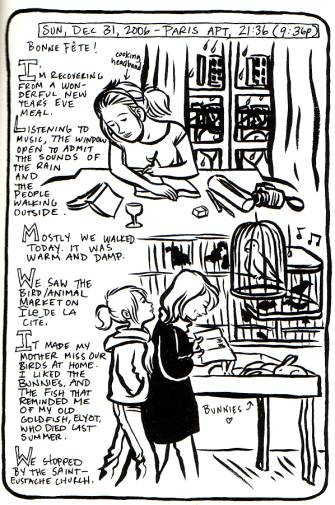

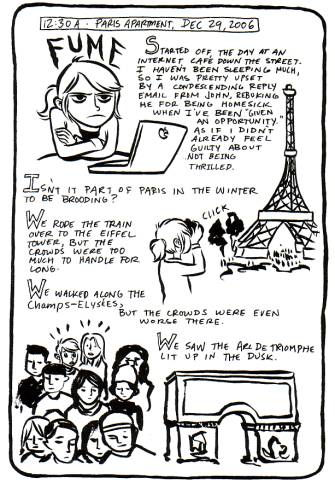

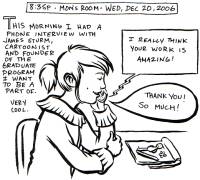

French Milk is the story of Knisley's early 2007 trip to Paris to live in an apartment with her mother for about six weeks, told in drawn diary form supplemented by the occasional photograph like the one attached to this paragraph.

The charm of

French Milk is that it's not about much of anything other than that trip. If there was a cathartic moment or a life-changing event somewhere in there, I missed it. But most travel is like that: a tiny portion of our lives raised just a little bit out of the stream of day-to-day living, something worth pondering even when -- maybe

especially when -- there's little in the way of a compelling, conventional narrative through-line. I enjoyed hearing the details. Knisley and her mother ate very, very well, saw great art and experienced more than few moments of gentle reverie. If you've never been on a similar trip, you may at least be able to remember what it's like to be in your early 20s and between things.

We did the interview via e-mail after a lengthy process of getting my request approved by the Simon and Schuster publicity team. Hopefully, I've not irked them in anything that follows. -- Tom Spurgeon

*****

TOM SPURGEON: I know very little about your life in general beyond what I've been able to glean from the book and your site. Is there anything specific you remember happening as a child that cemented your desire to become a cartoonist?

LUCY KNISLEY: My dad is a word man, and my mom is an artist. When they divorced when I was seven, I began reading Archie comics with a furious intensity. My dad disapproved of them, because they weren't works of literary genius, and my mom disliked them because of their sexist content. As a result of their disapproval, I had to think critically of the comics I was reading, and defend them to my parents. Every time I learned and new word or spotted a particularly nice panel, I would take note of it and store it up for ammunition. Now they look back fondly on my Archie adoration, and I see comics as a way that I combined my inherited loves of writing and art.

SPURGEON: How did you end up in Chicago?

KNISLEY: I went to four different high schools in three years, and wound up pretty freaked out by the experience. I finished up my junior and senior year in a little hippie school for artist kids, where they allowed us to spend entire class days in the studio, or in Manhattan on weekly field trips to the gallery district. I had a great teacher,

Wayne Toepp, who was a practicing artist, and someone who really encouraged me. I went from being this kind of troubled kid, to someone who had a handle on what they wanted to do.

Thanks to that school, and to Wayne, I ended up at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, which is a really nice school. I had intended to paint and make comics on the side, but in my freshman year, I found that I was pretty scarred, socially, from all my school switching in high school. I felt really distant and unable to connect with my classmates. I began to publish my comics in the school newspaper, as a means of communicating and identifying with the kids around me. That's how I met my friend and fellow SAIC alum,

Hope Larson, who really mentored me in becoming a professional comic artist.

I really love Chicago. It's fascinated me since I've moved here, in various ways. Sometimes it's this really American city, all new and industrial and shiny, and then you look beneath the surface and find all these hidden facets. After the great fire, all the new buildings were made of brick and adobe, because they wouldn't burn. Unfortunately, adobe is not a material that lasts in this kind of inhospitable weather, and it's begun to erode. The architecture here is a mix of fancy new glass skyscrapers, and crumbling, eroding old facades that are only really a few decades old.

SPURGEON: Has your interest in comics grown as you've become more interested in doing them?

KNISLEY: Weirdly, I've actually become less interested in comics as a reader since really getting into it in a professional capacity. I certainly follow my friends' and colleagues work, but I'm not as widely read as others, and I'm a little stodgy when it comes to picking up something new. I'll grab the occasional book at

Quimby's (a great Chicago indie comics mecca), but it's pretty rare. Part of this reluctance is that I've lost so many of the series I used to read as a teenager.

Strangers in Paradise by Terry Moore ended recently, and I've been a bit of a comics widow ever since. But a larger part of my skittishness has to do with the small world of indie comics. As someone who can and has taken large influences from reading comics, I know how easy it is for me to absorb a style of art or writing. I worry about the insular nature of this field, and how trends and fashions move through the comics world. As a result, I tend to stick to reading prose, and trying to keep my own work as a developing process away from too many influences, lest I fall into a familiar pattern or inadvertently rip someone off.

SPURGEON: Lucy, I thought I remembered, and the back cover copy confirmed, that

SPURGEON: Lucy, I thought I remembered, and the back cover copy confirmed, that French Milk

had a comics life before this edition from Touchstone. How did the book make the progression from one edition to the other? Who on earth did you get it to that you ended up with your first book from a New York publishing house? Can I ask how you entered into a business partnership with your literary agent? I know that might be a sensitive line of discussion, and certainly a private one, but I think a lot of young cartoonists wonder about having that kind of professional relationship and whether it's for them and how to get one.

KNISLEY: When I set out to journal my trip to Paris, I really didn't know that it would be such a momentous experience for me. I had this very imposing blank journal, that had been sitting on my shelf for quite a while. I thought, "I want to draw and write about my trip to Paris while I'm there," and brought the journal along. I supposed that I'd scan a few of my favorite pages to put up on my website, and maybe I'd eventually make a mini-comic out of the journal, if it turned out nicely. I ended up filling the pages every night, chronically a time in my life when I felt really displaced, and just so happened to be traveling in a foreign country. When I came home with this journal, really crammed full of vivid experiences, I didn't really know what to do with it. It was too enormous to make into a mini-comic -- I would never have gotten the staple through -- and it was too much of a whole to scan individual pages.

My mother, who runs a small publishing company with her husband, struck upon the idea of having it professionally self-published. She's always been behind the book, even when I had my doubts. So she helped me edit it and publish it through her self-publishing division, giving me the pride-and-joy discount. I took the self-published edition around to comic and book stores, and sold it online, where it started to get some buzz. I'm lucky enough to have friends in the industry, like Hope Larson, who liked the book and helped me promote it.

It wasn't until I took the book to MoCCA --

The Museum of Comic and Cartoon Arts Festival, in New York -- when it was picked up by my editor, who was seeking out promising young artists at the convention, to bring into her publishing house. A few weeks later, I had this giant, imposing contract on my lap, and I was pretty intimidated. I was graduating college, going off to grad school, moving across the country-- I needed help. I spoke with my friends, Hope Larson and Bryan O'Malley, who advised that I try to get myself an agent. Then I consulted with

Steve Bissette, who is my teacher at CCS and a long-time comic artist, and on the alert for when comic artists are being ripped off. I didn't think I'd know how to spot it when a big company was trying to rip me off, so I began to research the agents of cartoonists I admired. That's how I found

Holly [Bemiss], who has worked with

Alison Bechdel and others. I emailed her, and she called me the next day and we set up a working relationship, and I had an agent. She was really helpful in getting through the contract process, and now she sort of holds my hand and reassures me about a lot of the business stuff of being a comic artist. It's really nice, because I can focus more on the creative aspect of it.

SPURGEON: Were there any changes made between editions?

KNISLEY: Oh yes, lots of changes. There are a bunch of new pages that were cut from the original, that I spruced up. Some new photos, and many, MANY spelling corrections. I couldn't believe how many spelling mistakes I had made, but like I said, it was a journal, and I never thought of publishing it during the process of making it. The cover is also a little different, and my french grammar, which was usually phonetic and made-up, is much better now.

SPURGEON: Was there any worry that what you were putting together wasn't really hard hitting enough in terms of dramatic impact – that you weren't depicting any life-changing experience or anything like that? For that matter, how much refinement and editing was done? Is the book you made from day to day, or did you work from a script that you made day to day, or did you work backwards?

SPURGEON: Was there any worry that what you were putting together wasn't really hard hitting enough in terms of dramatic impact – that you weren't depicting any life-changing experience or anything like that? For that matter, how much refinement and editing was done? Is the book you made from day to day, or did you work from a script that you made day to day, or did you work backwards?

KNISLEY: Certainly, I've had my miserable times of doubt about the book. I look to meaningful works by beloved artists and I cringe, that my own book seems so shallow and self indulgent by comparison. But I've learned that it's better to judge a thing on it's own merits, rather than holding it up to the standards of other works, and that there is a great deal of value to be had in something that might be considered a little shallow or frivolous. In the book, I visit

Oscar Wilde's grave, where a bird craps on my head. Oscar Wilde upheld the belief in art for art's sake, and beauty for beauty's sake, which is a strong motivator for my own work. The bird crap might have just been a coincidence, but then again, it might have been one of those real-life messages not to take everything in my art so seriously. It's a travel journal, which allows for the inclusion of what I ate and saw and bought, but I think that there's a slow and subtle current beneath the surface, which is absorbed along with the sights and descriptions, the way you might come to your own unconscious realizations while traveling.

SPURGEON: What have people that have read the book responded to?

KNISLEY: Quite a few people seem to identify with the gaping chasm of uncertainty that I was experiencing at the time, being 22 and leaving college to enter an adult world. It's felt pretty keenly throughout the book, along with the new adjustments to a mother-daughter relationship as the daughter leaves the nest. I've also talked with readers about the guilt and isolation that can be felt while traveling in a foreign country and worrying that every moment isn't an idyllic postcard. Mostly, though, people seem to like the descriptions of food, and the francophile delights of shops and museums and streetcorners. I'm so glad I can bring that to the readers, and share my total love of that stuff.

SPURGEON: Your ending is very interesting to me in that I wondered for about the last third of the book how you would end it, and you do so in very matter of fact fashion, with a return to your apartment and drawing of your boyfriend. Did you know how you wanted to end it?

KNISLEY: I had absolutely no idea how to end the book, though I knew I would probably have to stop feverishly journalling my every move at some point. I set out to record the trip, and it's various vibrations in my life, and it was right that I stopped when I returned. I think that I wanted to leave it on a note where the reader felt that I was now able to look at the familiar life I'd come home to, and embrace it with a new regard. Paris was so consistently beautiful and ancient and glorious, that coming home can be such a disappointment. I think I wanted the reader to experience that melancholy, but also how my trip had become part of how I looked around, and how I faced and appreciated my life. My trip contained all this turmoil and passion, and when I came home it was much more peaceful and comforting. So the drawing of John asleep is a slower, more steady observation of the quasi-adult life I had stumbled home to.

SPURGEON: Speaking of that ending, I wondered because of the pacing of the last several pages if that material came from a bunch of pages some of which were left out. Did you every drop pages that you might have done because they didn't fit? Did you ever leave any out?

KNISLEY: I left out a few pages, but I also chose not to journal certain days. I spent the few days I arrived back from Paris sleeping and sitting around, so there wasn't much to journal. Also, there was so much less to look at. Returning home was simultaneously a downer and a relief. The obsessive need to document my experiences waned, and I think in the end of the book, there's a noticeable reduction in the feverish quality of my journaling.

SPURGEON: As someone who was just in a BFA program, what's your time at Center For Cartoon Studies been like? Do you work on very specific things; are you refining certain elements of your cartooning craft? What is it like to be there having sold a book?

SPURGEON: As someone who was just in a BFA program, what's your time at Center For Cartoon Studies been like? Do you work on very specific things; are you refining certain elements of your cartooning craft? What is it like to be there having sold a book?

KNISLEY: I went to CCS expecting something like a cartoonist's lodge, where we gathered around a cookstove in the woods and scribbled over our work in companionable silence. There were certainly elements of that, as it's located in the heavily wooded Vermont, where we did spend many hours drawing around any source of heat, but it's much more of a boot camp (and I say this with a great deal of fondness). It's grueling, and challenging, and you crank out work at a really high rate. I came from SAIC, which is a school focused on painting and conceptual artwork, and where I was forced to really fight for my right to make comics, which were not considered "Fine Art."

I spent four years in Chicago, seeking out teachers who would tolerate me working in this format, but they often could only contribute criticism and advice for my writing or my artwork separately. Much of my comics undergrad was generated by myself, as a combination of writing and drawing classes, combined with the connections I generated with professional comic artists who I met on the internet or at conventions. I was very much independent in my work, and had created a hard-won groove for myself, and become respected at SAIC for making comics for a fine arts degree. When I arrived at CCS, I was suddenly surrounded by teachers who examined both elements of writing and artwork together, and could reference comics and graphic novels to compare to my work. It was a totally new experience, to be working with the teachers and making comics, rather than fighting for my right to do so. I chafed a little, forced to work less independently than I was used to, but eventually I found a way to work that better incorporated the input I got from the teachers and students. It was a little awkward, entering the school with more professional comics experience than some of the students, and a little frustrating in the first few months when we went back to basics to get everyone on an even keel.

It was great to be surrounded by passionate comic artists, though, and people at many different levels. Comic artists are intense, often slightly socially awkward people, though, and while I am very fond of CCS, it was a hard environment in which to work, especially for someone like me who is most productive when given a lot of leeway to work independently. I think my time at CCS is helping me a great deal, to work with other professional comic artists and develop myself among people who know this milieu so well. And the teaching and guest lectures at CCS are unbelievable and unique -- where else will you learn from and meet

Lynda Barry one week, and

Garry Trudeau the next?

SPURGEON: Did you every worry in the course of making the book in terms of keeping certain narrative threads alive? There are some throughlines, but did you ever worry about things, "Oh, I have to tell them how this worry of mine turned out" or how a certain trip ended?

KNISLEY: In my second edition, I brought in a few pages that wrapped up a couple things, but I tried not to let it bother me too much. It's honestly a journal, and it's going to have some loose ends, and feel a little scattered. I wanted to leave my story open-ended, while still retaining some resemblance to "a story."

SPURGEON: How did you decide when to add photographs and when to exclude them? Was it simply a matter of using what turned out well considering your limited interest in taking photos, or were you going for a certain effect shifting from cartooning to photography?

KNISLEY: One of my absolute favorite things, when I read, is frequently flipping to the author page to look at the picture. I don't know how many other people do this, but when I read, I like to be connected visually to the writer. With comics, it's a little easier, because you can see their drawings and their hand in the work. I still love to see pictures of the creator. Perhaps it's something to do with me being a very visual person, who enjoys having a face to accompany a writer's voice. In non-fiction or autobiographical stories, the desire to see an actual photo, beside their a representation or description, is something I have always felt. When you see something drawn or read something described that you know well (When I read

David Sedaris' description of the Anne Frank house, for example), there's this jolt of recognition and pleasurable connection to the writer, through shared experience. My inclusion of the photos from my trip were an attempt to strengthen my bond with the reader. They not only get to experience my observations in the reading, but they get to see my impressions, and then turn the page and see an actual photographic representation. It proves it was real and gives the reader another facet of experience in reading about the trip.

SPURGEON: One of the entries in the book indicates that you have cartooning friends, certain peers that you look to for advice or feedback. Is that true? What have those relationship done for you in terms of your development as a cartoonist?

KNISLEY: There's a great, and sometimes small community among independent comic artists. I'm lucky enough to know some incredibly talented people, from who's advice and example I've learned a great deal. Hope Larson is likely the strongest influence in my development, as she was the first comic artist with whom I struck up a real friendship, during our briefly overlapping time at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. I continue to depend on her advice and opinions. She and her husband,

Bryan Lee O'Malley, are good friends, and really helped me get started as a comic artist, by bringing me to conventions and introducing me to the community. This network of comic artists are a great resource, as I can monitor their work on the internet, and be aware of their excellent progress, while also turning to them for advice or criticism or reassurance. I have a good group here in Chicago that I meet with every week, where we discuss our professional experiences, but mostly we just eat cupcakes and draw together. It's really important to have a number of people in your life who can understand and sympathize with what you do, even if you never discuss it. It's just nice not to feel alone, when you're hunched over your drafting table at three in the morning.

SPURGEON: Was there any specific influence on this work? French comics have a tradition of travelogues, and Craig Thompson is one American cartoonist that's done a work in that style… was there anything in comics or outside of comics that informed French Milk

?

KNISLEY: I often keep note of my experiences through journal comics, but Craig Thompson certainly opened my eyes to the possibilities of such a thing with

Carnet De Voyage. I think that

French Milk was influenced by the written stories of Paris that I have loved, and read or re-read around the time I was preparing for my trip.

Edmund White has written quite a bit about his time in Paris, and

La Flaneur is a favorite read of mine. I also read

Ernest Hemingway's A Movable Feast, which I believe influenced my dedication to description in my writing, and enhanced my experience of Paris.

Anais Nin, who gets around to alluding to her surroundings in her sensual writing, is another favorite, who likely flavored my attempts. I also took inspiration from

David Sedaris, (who is mentioned in

French Milk a few times) in his writing about his experiences as an American living in France, and the hilarity that can ensue from the cultural or language barriers.

I'd love to say that I read

Elaine Dundy's The Dud Avocado before my trip, and that

French Milk's resemblance is intentional and thought-out, but I was given the book by my father a few months after my return.

The Dud Avocado is a novel, though written in the first person, from the perspective of a 22-year old American girl who has come to Paris to become an adult (during the fifties). When I read the book, I was stunned at some of the elements of the book and their resemblance to exactly what I had tried to convey, and with how much more eloquence and flair she had done so. They are very different books, of course, but I have to cite Elaine Dundy as an after-the-fact influence, as my perception of

French Milk changed after I read

The Dud Avacado.

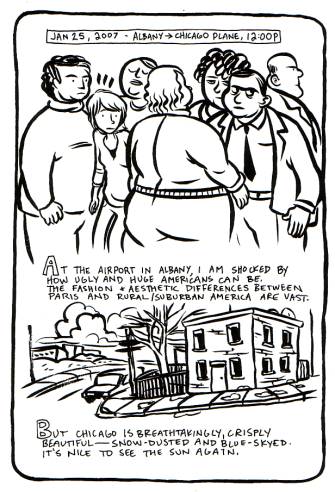

SPURGEON: I thought it was interesting that you did very little in terms of comparing and contrasting elements of your life in the US and that specific stay in France, and what you did was almost all back in America -- noticing the numbers of heavy people, a really nice panel that draws a comparison between Chicago to Paris. Is there any reason do you think that you didn't do more of this while in Paris, or go back into the book and do it?

SPURGEON: I thought it was interesting that you did very little in terms of comparing and contrasting elements of your life in the US and that specific stay in France, and what you did was almost all back in America -- noticing the numbers of heavy people, a really nice panel that draws a comparison between Chicago to Paris. Is there any reason do you think that you didn't do more of this while in Paris, or go back into the book and do it?

KNISLEY: I suppose I assumed that it was pretty obvious from my descriptions of Paris that it was a world away from America. You notice the difference so much more when you return. Paris was such a riot of distracting images and tastes, that comparing it much to America was off my radar. I wanted to immerse myself in the foreignness of Paris, noticing the loveliness without directly drawing a line back to it's difference from American cities.

SPURGEON: I was wondering if you could talk a bit about one of the themes that in your introduction you suggest may be a part of the work. You say one of the meanings for "French Milk" is a reference to your own struggle for adulthood. While I see that throughout the book, I'd like to hear your view on what was significant about that trip in terms of that particular journey.

SPURGEON: I was wondering if you could talk a bit about one of the themes that in your introduction you suggest may be a part of the work. You say one of the meanings for "French Milk" is a reference to your own struggle for adulthood. While I see that throughout the book, I'd like to hear your view on what was significant about that trip in terms of that particular journey.

KNISLEY: Most adults in America don't drink milk past their adolescence. The title refers, beside to the obvious "mother's milk" aspect, to my voracious appetite for something that is traditionally thought of as a children's beverage. There is a literary connection between milk and comfort or immaturity. When I came home and read through the journal, which mentions my admiration for the sweet, fresh milk that I drank in Paris, I began drawing a connection between the underlying emotions I felt during the trip, in struggling with my mom getting older and having to grow up myself, all while I found the taste of the milk, or childhood, so particularly sweet. It's about savoring something ephemeral, like a trip that won't last forever, or the safe and comfortable feeling of being your mother's child.

The trip took place in the winter before I graduated from college, meaning I had one semester left to me before I had to move on, and accept the responsibilities of becoming an adult. My mother, becoming older and used to my absence from home, was becoming a separate entity from my mom figure I'd know as a child, and our relationship was changing on that trip. She was becoming more of a friend and less of a protector, and her life and mine were deviating, though this was pretty subtle. There's something about that trip that forced me into these realizations -- I don't know if it was my feelings of being "un-homed" in such a foreign environment, or the strange familiarity of Paris, and how easy it was to slip away and become immersed in the culture, that began to root my mind in this idea of leaving childhood to arrive in the foreign and confusing culture of young adulthood.

SPURGEON: I know that you probably don't have a ton of ways to make comparison, but how has Touchstone been as a publishing partner on this book? Is there anything that's surprised about the process of getting a book out there? Is there anything you're looking forward to in terms of the publicity support you're providing for the book?

KNISLEY:

KNISLEY: It's been a long and confusing process, but very rewarding overall. I come away from this experience as someone who has managed to, at least in part, bring graphic work into a traditionally literary publishing world, and I'm happy to have been a part of that bridge. My editor at Touchstone has been really understanding and patient with me, and all my confusion and inexperience. I had no idea that the editing process would be so long or labor-intensive. I'm looking forward to the book talks and signings, even as someone who considers herself to be pretty shy, and I'm happy to be moving on to new projects in the hopes that I'll be able to keep up a steady production clip.

SPURGEON: What's next for you, Lucy? If you don't know exactly, is there a specific kind of comic you'd like to explore?

KNISLEY: Right now I'm working on a couple projects, but mainly focusing on a graphic novel of short stories detailing my experiences with food, and growing up with a chef for a mother. I found that the culinary aspects of French Milk were really interesting to me, and food comics are not something I've seen a lot of, whereas food writing is pretty popular. The addition of drawings to writing about food, I think, can be really lovely, and I'm exploring that at the moment. I'm very fond of a little book by

Claes Oldenburg and Coosje van Bruggen, called Images a la Carte, which contain these incredibly beautiful watercolors of architectural restaurant dishes. The pictures of food tell this beautiful story, and I've been trying to do something similar, through comics. Really, it's autobiographical, but I tell my stories through memories of food, and growing up in Manhattan restaurant kitchens. It's much more conceived and careful than

French Milk, but just as full of enthusiastic description and edible evocations.

*****

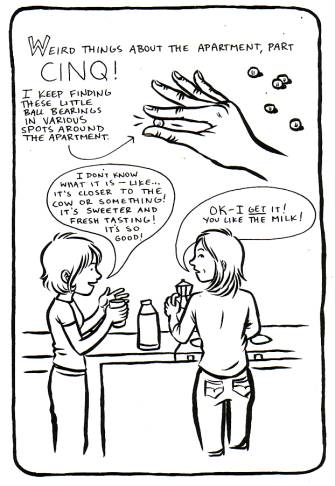

* all images from

French Milk

*****

*

French Milk, Lucy Knisley, Touchstone/Simon and Schuster, softcover, 9781416575344, 200 or so pages, 2008, $15.

*****

*****

*****

posted 9:00 am PST |

Permalink

Daily Blog Archives

November 2019

October 2019

September 2019

August 2019

July 2019

Full Archives