August 29, 2015

CR Sunday Interview: Robert Goodin

CR Sunday Interview: Robert Goodin

******

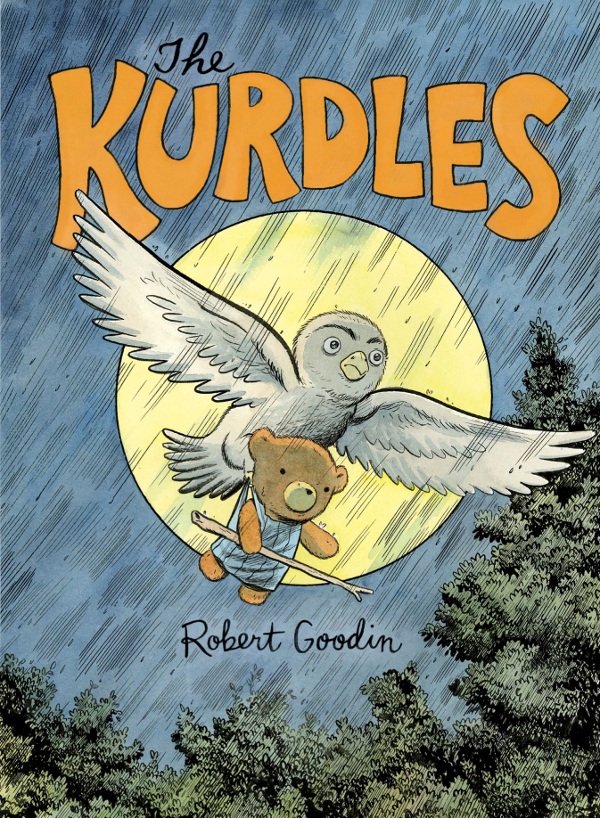

I was super happy when

Fantagraphics announced they were doing

The Kurdles with cartoonist and animator

Robert Goodin. Goodin is one of those talents that's been around for years and years, can clearly draw anything he wants in evocative fashion, has a unique voice as a writer, even, but has never put together that one book. I wish this were a list of one, although even one artist left behind as it were is too many. He has a number of excellent-looking

mini-comics to his name:

Après-Shampooing and

Binibus Barnabus are the two I remember best, but his site mentions

The Fish Keeper,

Pig's Missing Poo and

The Suicidal Dog. All of those titles are good enough to have out there just for the titles even if they aren't attached to a comic. A recent flourish of activity saw

The Man Who Loved Breasts land at

Top Shelf, and Goodin contributing to the anthology

MOME. Along with

Seth, he has kept the tradition of high production value physical holiday cards alive and well.

I'm happy to report that I quite enjoyed

The Kurdles. It has the odd bounce and stumble that my favorite all-ages books have; this determination that kids have to explore an area at their own speed, consequences be damned. I had no idea where it was going on any page past maybe the second, and would have little to no idea where a sequel might take us. That uncertainty is a gift, particularly for a book as visually rewarding as this one is. Hopefully we'll get to find out what happens when a sequel book is announced. -- Tom Spurgeon

******

TOM SPURGEON: Rob, I know it's a standard question, but I've known you for years and seen you at shows since I've been going to them but don't have a sense of how you became a cartoonist. Do you mind walking us through how you ended up drawing in a professional capacity, what your relationship to comics has been like/

ROBERT GOODIN: I decided I wanted to draw comics when I was about 12. Back then the dream was to pencil a superhero comic. I stuck to this plan through high school, drawing constantly in my free time. As I approached the end of high school, I started getting bored with superheroes. My interest probably peaked in '86 or '87 when so many exciting things were coming out, but I was becoming increasingly disappointed by what followed. As I entered college as an illustration major at Cal State Long Beach, I was reading very few comics. One of them was

Cerebus, a bit of a gateway drug out of the superhero tunnel vision. I was also beginning to read

The Comics Journal more often, which happened to be when you were editing it. What really changed me was when a teacher brought a photocopy of Dan Clowes's "Art School Confidential" to class. Evidently this was circulating around the Los Angeles art school scene at Otis, Parsons, Art Center, and now Long Beach. I hunted down some

Eightballs and the floodgates opened. Soon I was picking up

Maus,

Raw,

Jim,

Rubber Blanket and anything by Charles Burns. Naturally the

Journal was key for me at this time. It was very exciting.

Once I graduated from college, I needed a job. My dream was to draw comics, but I still had a lot to learn and I needed to pay rent. A high school buddy of mine, Joe Orrantia, was working on

Ren and Stimpy while I was attending school. I saw that a steady income could be made while still learning a lot on the job. It was like a masters degree that could pay me instead of the other way around. I set my sights on the animation industry and after a year and a half of rejections, I became a background artist on

Duckman in 1995.

After a few months at

Duckman, a fellow background artist who used to be a colorist at Malibu Comics brought up the idea of doing a comic anthology with our fellow work artists. His name was Albert Calleros and the two of us, along with another ex-Malibu guy, Larry Reynosa, put out

Hot Mexican Love Comics. The artists chipped in 60 bucks per page. We took it to some conventions and I started to think I'd like to do a more ambitious anthology that I would pay for myself. It would be inspired by

Raw and the Drawn and Quarterly anthology with very nice production values and it would be under my own company name, The Robot Publishing Co. I named it

Oden. Sadly, it flopped and I lost a ton of money.

I would go on to publish smaller books hoping that it was the expensive price tag that was the reason

Oden didn't do well. Those books flopped as well. After losing quite a bit of money over two to three years, I threw in the towel on publishing. It was crazy anyway. I couldn't successfully have a career in animation, and be a cartoonist, as well as a publisher. I was insane. Since then I've focused only on animation and my own comics.

SPURGEON: The Robot Publishing stuff was beautiful and ahead of its time and in retrospect seems quite doomed from inception. What are your memories of that effort overall, and Binabus Barnabus

specifically? Because it was amazing in that you were so right there with the fully-realized style right away. What do you think of that work now?

GOODIN: I'm really proud of what we did. here were primarily eight of us in this collective and I think for our experience level, we all did a great job. I'll always wonder what could have been if we had more time to hit our stride more and find an audience. At any rate, there was a lot of really talented folks in that group that have gone on to great things.

Binibus actually strikes me as a little bit of an outlier from my other stuff, at least in terms of drawing style. That book was really inspired by mid-century cartoons like the UPA animation studio, the cartoons of Ward Kimball and VIP. However, in terms of story, it does have a bit of a fable quality that has been a thread through most of what I've done. I still like the story, but I'd probably draw it differently now. I guess I'd draw most of early my work differently now.

SPURGEON: The other period in which I remember us seeing your work is maybe eight, maybe ten years ago, when you did both

SPURGEON: The other period in which I remember us seeing your work is maybe eight, maybe ten years ago, when you did both The Man Who Loves Breasts

and the short piece that appeared in MOME

. I assume that the non-comics part of your career was well established at this point, so what was that particular move at that time? Did you just have time to do work?

GOODIN: That was during a time when I was out of animation for a while. I had been working at Klasky Csupo for about eight years and I was a storyboard artist for about five of them on shows like

The Wild Thornberrys and

As Told by Ginger. At the turn of the millennium, I was also going through a lot of life changes. There were a few deaths in my family and I also met my wife, Georgene. Klasky was going through a major contraction and losing all of their shows. I think they only do commercials now. The writing was on the wall and I was not only burned out, but after these deaths I was really wondering if working so hard in animation was worth it. Georgene and I decided to get married and take a yearlong honeymoon in Paris where we would work on our dream projects.

Things didn't quite go as smoothly as we would have liked, but we did spend a year in Paris and I stayed out of animation when we came back. I was still very tired of it. I wanted to try to make it as an illustrator and cartoonist. It was during this time that many more of my comics were popping up. Thematically they're all over the place. I was still trying to figure a lot of things out (and still am). The downside was that I was making no money. Georgene was the main breadwinner at this time and we were constantly broke.

At one point I got a call from my old

Hot Mexican Love Comics pal, Albert, and he needed some help on an episode on

American Dad. I came in and ended up sticking around as a storyboard revisionist. A revisionist is typically an entry level job for storyboarding, but it isn't nearly the grind that being a regular board artist is, so I stayed and am still there eight years later. Naturally, my comic output dropped again, but I can pay the mortgage.

SPURGEON: What in general drives you to continue to do comics? What specifically about that form appeals to you in terms of personal expression?

GOODIN: It's an obsession that has never waned. I get depressed if I'm not doing it for very long. I think you nailed it in terms of personal expression because it is so personal. The work I do for my day job is completely impersonal. I draw in someone else's style, using shots that someone else decides, drawing out someone else's script. It's very machine-like, but in animation it's necessary and suppressing one's ego for the benefit of all isn't necessarily a bad thing.

However, for me, there's nothing like falling into a world created by one person, who has a distinct writing voice, a distinct ink line, and a vision that is unique. Pauline Kael wrote a critique about Jean-Luc Godard fairly early in his career that has always stayed with me. She comments on how he was distinct from the rest of cinema's history in that he was able to do what he wanted to do. He didn't have the political and economic obstacles that every other director that came before him had. He was free to succeed or fail purely on his terms, not because of producers changing his vision. One of the beauties of indie comics is that anybody can and does have this freedom. It doesn't mean what we produce is any good, but in a world that is even more dominated by corporate entertainment than it was in the '60s, you can't beat it. We are all

auteurs.

SPURGEON: [laughs] You're a really skilled, facile artist. Is it frustrating at all to work in a milieu -- alternative comics -- where that sometimes isn't appreciated as it is in more commercially-driven forms and expression. It's not like it is never appreciated, but there is an intermittency to it.

GOODIN: This is an interesting question that I think I could answer in a 100 different ways depending on my mood. First of all, thanks for the compliment, I really do work hard to be a solid storyteller who is in control of the story that I'm telling. It's important to me to not have the reader struggle with what I'm communicating unless I want them to.

In terms of whether those skills are appreciated in indie comics, it's hard to say. I think there are a ton of alternative artists out there that are very, very skilled. There are also a percentage of books I see where I think these skills are either not seen as being important in indie comics or people simply don't have the chops. It probably depends on the artist. There are a lot of people experimenting with ways of telling a story in alternative comics, which is great. Sometimes I think it works better than others, but that's the nature of art. What can drive me crazy is when I can't tell people apart, actions become a mess, or I don't know what panel to read next. If this is the intention of the artist and it has a point, that's fine, but a lot of times it's just a failure or storytelling and I never want to do that myself.

At the same time, I can also feel like my comics are conservative in terms of how they are told, maybe even square. I'm not one to experiment too much formally, but I also am not a fan of the mechanics of the story becoming the focus and bringing attention to itself. In my mind, that's putting the cart before the horse. Of course it would depend on the story and if it's appropriate and works, then that's great. See what's happening to my brain here? I start spinning around. Ultimately I'm not the kind of personality that is likely to write a manifesto about the one way comics should be done. I'm a fan of both Hitchcock and Godard and they approached film in very different ways.

SPURGEON: So why an all-ages work? How did this one develop? In fact, how do most of your projects develop? Do you start with an idea, do you work in sketchbooks?

GOODIN: This came about largely out of necessity. During my time out of animation, I was desperate for some kind of paying work. While I was at SPX I met an editor at

Disney Adventures who thought I should submit a pitch to them.

Disney Adventures actually printed creator-owned work and I thought that this could be the perfect answer. I put together a pitch of short story ideas for the Kurdles and sent it over. It sat there for about a year and then the magazine folded. By this point I had become rather excited about this world I'd created. I thought that it could hit the sweet spot of doing something that might make a little money but not feeling like a sell-out. I realized that I could still bring in themes that I wanted to deal with within the framework of an all-ages comic. I then considered doing it as a longer form book and sent it to my

MOME editor, Eric Reynolds, at Fantagraphics and he was up for doing it.

I do work in sketchbooks but it's sporadic. I do have a Kurdles-only sketchbook that is mostly filled with notes and bits of dialogue that has helped me understand these characters and gives me the building blocks for new stories.

SPURGEON: I love the opening sequence in this, the way Sally moves from one world to another. Sally isn't wanted. Why made you go in that direction rather than create a character that might more enthusiastically wish to go home? What was important to you about showing that move from "our" world to the milieu in which most of the story takes place.

SPURGEON: I love the opening sequence in this, the way Sally moves from one world to another. Sally isn't wanted. Why made you go in that direction rather than create a character that might more enthusiastically wish to go home? What was important to you about showing that move from "our" world to the milieu in which most of the story takes place.

GOODIN: I think I worked backwards with this. I had these characters and the world, but I needed a way to bring the reader into it. Having Sally function as the stranger in a strange land helped meet that need. At the same time, once I got her there, I needed a reason for her to stay, so I made the option of returning really unappealing.

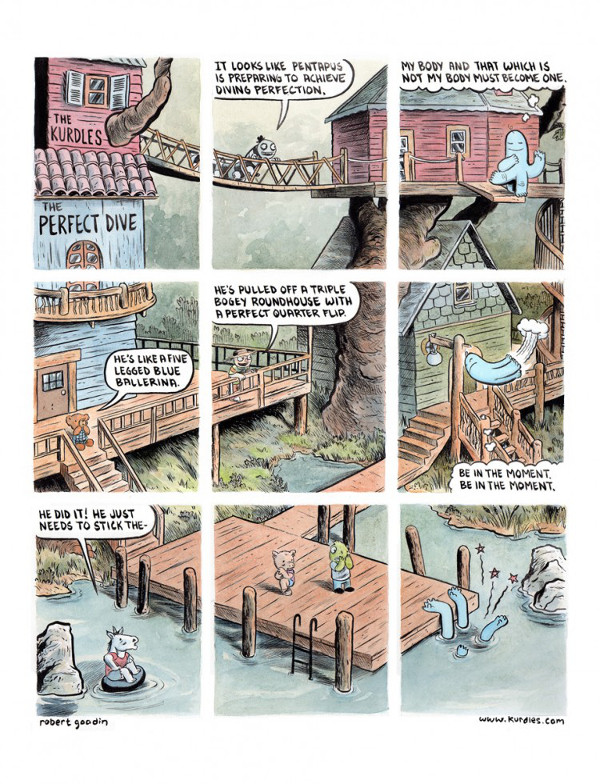

SPURGEON: You use a variety of storytelling techniques on the page: big images, close sequential progressions, even standard narrative jumps: can you talk about designing the pags up front, how you did that, what makes one page three panels and another page ten? Even when you use more standard page grids you do them with a twist, like a contiguous background.

SPURGEON: You use a variety of storytelling techniques on the page: big images, close sequential progressions, even standard narrative jumps: can you talk about designing the pags up front, how you did that, what makes one page three panels and another page ten? Even when you use more standard page grids you do them with a twist, like a contiguous background.

GOODIN: I guess I'm not much of a grid guy. Perhaps it's because my day job is spent drawing in the same sized box so I can't bring myself to do it at home. I think the only time I ever used it was for my

George Olavatia: Amputee Fetishist story which was really about the rhythm of the dialogue so the grid helped.

With this comic, I wanted it to feel organic and flowing, not constrained by something rigid. I think it also depends on the pages and what I'm trying to do. For example, when Sally is chucked from a car in the rain and starts to move for the first time, I thought her movement was what this sequence was all about, so the panels are relatively small and the same size focusing only on her and nothing else. When the page turns, there is a larger panel to show how small and alone she is in this world. The panels get small again as she moves out to the road, but open up again when she is almost taken out by a truck that fills the page.

Another reason I vary things so much is I sometimes want you to focus on one part of the page more than another, so I might make a panel bigger, or I want the reader to slow down a bit. Other times, I can feel like I'm getting in a rut and want to mix it up, so in that case it's also a gut thing.

SPURGEON: How did you work with the color in the transitional stage? The first page where we see all of the protagonists at once is very striking in terms of the lightness of the colors, and I wondered how much of that was intentional... how comfortable are you with color, generally, is there an aspect you feel a need to catch up a bit?

GOODIN: That was a big source of anxiety as I started this. I hadn't used color too much in comics before this and when I had I wasn't entirely happy with the results. When the Kurdles are introduced, the colors are intentionally lighter. It was a mood change and I wanted that reflected in the color. For the most part, I'm very happy with how the color came out, because I really thought it could have been a disaster. I have strong opinions about coloring, but I wasn't sure how to do good coloring myself. Now that I have this book under my belt, I feel like I avoided a catastrophe. Going forward I'd like to use bright colors a little less and let the ink do a little more of the work. I tend to prefer muted colors with bits of brightness for accents.

SPURGEON: What if your appraisal of your own skills as a character designer? How much did you work on each character, and did you shift characteristics around a bit before you were satisfied with each one?

GOODIN: They popped out more or less fully formed. Maybe in the case of Phineas I should have worked him out a big more. It bothers me that he's a bit of a scarecrow, it's too close to Oz. I should have pushed that farther and I think I'm going to deal with that in future books.

I like that they're easily distinguishable and I go crazy when I can't tell characters apart in comics. It seems like a major failure on the part of the artist. Beyond that, I'm pretty happy with them. I like that Sally basically has two expressions, as does Pentapus. That may be another part of me rebelling against animation and its big expressive eyes.

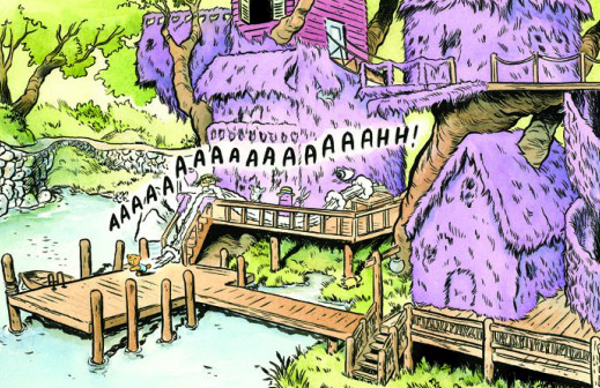

SPURGEON: The central narrative of the second two-thirds of the books is basically having the characters interact and work together to remove a layer of fur from the house. This is an extremely fascinating choice, and I wonder how you landed on this one.

GOODIN: I really, really struggled with the plot of this book. I think my biggest weakness as a writer is plot. I like writing dialogue, but giving characters a story to hang it all on is very difficult for me. Up until this point all of my stories were short and just popped out of my head. This was different in that I had these characters that I wanted to do something with and I needed a story. It felt artificial, in a way. I started with what I didn't want to do because it had become too played out: no chosen one hero stories, no evil antagonist, no stated life lessons, etc. I remember writing down ideas and dismissing them as clichés. It wasn't until I came up with their house having a disease that grew hair that I finally felt like I had something I could work with. The solution to this problem would be the framework for the character interactions that I really enjoy. Something I was concerned about was that this was not exactly an exciting third act and most of the action happens in the first 10 pages. With the help of Georgene, I was able to throw some things involving Hank and a door that spiced it up a bit.

SPURGEON: How important was it to you that the various characters being distinctive even worked together towards the same goal? Did this plot provide any difficulties in doing that? Is there a character moment, a contrast between two of the characters, that you're particularly proud of?

GOODIN: It's funny because when I started thumbnailing the book, the characters were not that distinct from each other, especially the boys. In fact, I needed to switch some dialogue from Hank to Pentapus because I realized over time that it was not longer in character for Hank to say. The thought of some of them bickering but needing to join forces was never much of a conscious thought, it just began to emerge as the story developed.

I think of all the character interactions I'm most proud of it would be Sally saying one thing and meaning something else. She's in a vulnerable situation and she needs help, but it's hard to ask for help and she's not entirely sure she can trust these guys yet. She went through some real trauma the day before and it's going to take some time for her to talk about that if she ever does. I wanted things to be communicated without being said and that can be tricky with a bear that only has two facial expressions. Hopefully, I pulled it off.

SPURGEON: Can you talk about why you did the "we're stuck with you moment" out of panel-bordered panels?

GOODIN: I wish I could remember why exactly, but it's been a few years since I roughed out the story. I like that for that moment, it's just about those two characters, Hank and Sally, who have been getting on each other's nerves all day. There's no background or even a panel border. I also just like a page to breathe every now and then. Panel borders are a little constraining sometimes. I like to open things up.

SPURGEON: That last sequence is about as charming as they come as Sally explores this space she has -- maybe the first time she's had space -- and then declares her satisfaction with it. At what point did you find this ending for the story? Had you tried another?

SPURGEON: That last sequence is about as charming as they come as Sally explores this space she has -- maybe the first time she's had space -- and then declares her satisfaction with it. At what point did you find this ending for the story? Had you tried another?

GOODIN: It's funny that you bring that up, because the last page actually was redrawn. I had the entire book roughed out and showed it to Georgene for her to read. The last page was similar, but it was of Sally looking over the lake at sunset saying, "I think I'm going to like it here." Georgene looked at it and thought we needed to see the house one last time, and for the first time fully removed of fur. I grumbled because it's a ton of work drawing that thing, but I knew she was right. [Spurgeon laughs]

I grew up as a military brat and moved around constantly. It's a very satisfying feeling being able to look around where you are, be happy with it, and know that you're home.

SPURGEON: Is this a kind of work in which you'd like to do more work?

GOODIN: Absolutely! I'm working on a follow up right now and have posted some short stories on my website:

kurdles.com. As I worked on this, I found that I can still deal with a lot of the same themes within an all-ages comic as I do for

MOME. I may need to bury things a bit deeper, but kids go through a lot. The world is a tough and confusing place to navigate and a stuffed bear being dropped into a world where fur grows on trees works as a pretty good metaphor for that. I also really fell for the characters while working on this and want to do more stories with them. I would like to do at least two more books -- I have them plotted -- give it some time to find an audience, and see how they do. In a lot of ways, a lot of things came together for me in

The Kurdles. The characters become richer and the world more fully realized in the stories that I have planned. I wish I could do this full time.

******

*

The Kurdles, Robert Goodin, hardcover, 60 pages, 9781606998328, May 2015, $24.99.

******

* the cover

* a photo of Rob from 2013; by me

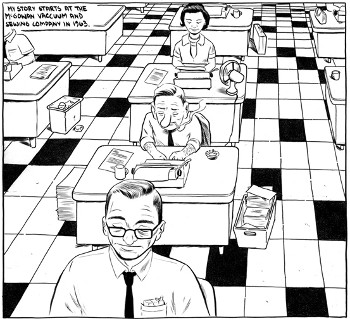

* an image of Goodin's earlier work

* multiple full pages or substantial panels from

The Kurdles, supplied by Fantagraphics Book. Includes the below piece.

******

******

******

posted 7:00 pm PST |

Permalink

Daily Blog Archives

November 2019

October 2019

September 2019

August 2019

July 2019

Full Archives