May 11, 2010

Frank Frazetta, 1928-2010

Frank Frazetta, 1928-2010

By Tom Spurgeon

Frank Frazetta

By Tom Spurgeon

Frank Frazetta, an artist that enjoyed a decades-long career in comics before ascending to pop culture icon status as a painter of powerful fantasy imagery,

died on Monday in Fort Myers, Florida from complications due to a stroke. He was 82 years old.

Frazetta was born in Brooklyn in 1928 as Frank Frazzetta. He would drop the extra z as a schoolboy due to aesthetic concerns (he didn't like the way the second z looked in the same name with two t's). Like many talented young artists, among his first memories of making pictures was a commercial consideration: selling artwork and roughly done comics to eager schoolmates. An early beneficiary of the many opportunities for art training that existed in New York's public schools in the first half of the 20th Century, Frazetta took courses at the Brooklyn Academy of Fine Arts from the age of eight under the tutelage of an artist named Michael Falanga.

Frazetta described his training

in a 1994 interview with Gary Groth at The Comics Journal. "He'd [Falanga] come and see where I was working and he might say, 'Very nice, very nice. But perhaps if you did this or that." That's about it. We never had any great conversations." Frazetta cited a number of his fellow students as equally important in learning how to make art, as well as studying the work of cartoonists like Milton Caniff.

Frazetta was one of a handful of precocious teen artists that found work in the first decade of mass comic book consumption before and then directly after World War II. According to his entry at the Lambiek site, Frazetta's first job in comics was assisting

John Giunta, then a member of Bernard Baily's studio. His first published work was the Snowman story that appeared in December 1944's

Tally-Ho. Frazetta worked for Fiction House during roughly this same period, doing assistant's work cleaning up the by-market-demand, furiously performed artwork of veterans like Bob Lubbers and George Evans. His final apprenticeship came at Standard/Nedor soon after Fiction House. There the young artist became a skilled maker of funny animal comics, placing work in such titles as

Supermouse and

Happy. According to

a biography assembled by art and books dealer Bud Plant, Frazetta's work in those first few years was providing illustrations to text stories that were included in the various Nedor magazines.

Between 1946, when Frazetta did his first solo work for Prize Publications'

Treasure Comics and 1948, when he began to take on a veteran's workload in terms of active art assignments, Frazetta began to flower as a comics artist. His pages during the 1948-1951 became much more his own, more idiosyncratically drawn and lovely to look at, much more effective comics in terms of flow and tone. His clients expanded to include DS Publishing, Eastern Color, DC Comics, Avon, American Comics Group and Magazine Enterprises. Most of his comics during this period were adventure-oriented, including a well regarded run of "Shining Knight" six-pagers that ran in

Adventure Comics in 1950 and 1951. Other series on which Frazetta worked included "White Indian" in the

Durango Kid title.

In 1951, Magazine Enterprises reached out to Frazetta, hoping to secure a more structured and more profitable relationship with the young cartoonist who admitted later he was still as interested in playing baseball -- a naturally gifted athlete with acrobat's physique, he was once offered a tryout with the San Francisco Giants -- as he was in art. The result was Frazetta's first solo comic book series, the jungle adventure

Thun'da, which ran for six issues in 1952 and 1953. Frazetta did not commit back to Magazine Enterprises. He added Toby Press, Prize and EC as clients to his already crowded list. Frazetta enjoyed a second run on a name character at DC, this time on the

Tomahawk feature. He created a comic strip for the McNaught Syndicate called

Johnny Comet (later

Ace McCoy that ran for only a couple of years. It wasn't his first gig in strips, having ghosted for Dan Barry's

Flash Gordon in a period just prior to launching his own feature. He even began a limited focus on covers-only work during the early '50s, suggesting an eventual direction and specific for the cartoonist's career in future years. His "Buck Rogers" covers for

Famous Funnies are some of the most-lauded mainstream comics covers of all time.

Given the nature of his skill, his time at EC wasn't as fruitful for Frazetta as it would be for many of his peers. He created a handful of well-regarded stories, with "Squeeze Play" likely making the greatest impression. That story appeared in

Shock SuspenStories #13 in Spring 1954.

In 1953, Frazetta began work for Al Capp as an assistant on

Li'l Abner in part to make some money in a more structured way than may have been available to him in the rapidly shrinking and always chaotic American comic book industry. Capp offered him $100 a day for five days' work in Boston. He would need it, marrying Eleanor Kelly in 1956 (on Sadie Hawkins Day) and starting a family with her soon after. He would continue to work for Capp until early 1961, moving the bulk of the work to his home studio. In exchange for the stability involved, the assignment involved infrequent trips Boston, working for the parsimonious and famously difficult Capp, and doing work not his own for an extended length of time. Frazetta's run on the strip is regarded by some comic strip fans as a highlight of that feature's middle years and by some Frazetta fans -- and perhaps Frazetta himself in the years right after -- as a frustrating side journey that took the artist away from many of the things he did best. He left the job when Capp demanded he relocate to Boston.

Upon his departure from Capp, Frazetta quickly discovered that the comics market had changed just enough to gently nudge him onto its sidelines. Unaccustomed to being on the outside looking in, it was during this period that Frazetta did work for various Men's Magazines, work later reprinted in books like

The Sensuous Frazetta. He assisted Harvey Kurtzman and Will Elder for a time on the solidly lucrative

Little Annie Fanny feature they were doing for

Playboy, although it's unclear if that ever felt like a long-time gig to the briefly struggling artist.

In 1964, Frazetta forged a relationship with Jim Warren and his fledgling empire of genre-driven magazines. He would do one major interior story but soon switch to covers and the kind of iconic single-image making that was increasingly dominating his professional life. Frazetta's art on the Warren Magazines

Creepy,

Eerie and eventually

Vampirella combined some of the pulp tendencies for which he was soon to become very well known with a sense of classic horror. They remain some of the company's most iconic pieces of art, and many were re-used in the 1970s as the companies did more in the way of special issues and compilations. He also did the covers for Archie Goodwin's short-lived

Blazing Combat, some of the most somber and fascinating pieces of art the painter would ever attempt on behalf of a comics company. Although much fewer in number than their reputation might have you believe, Frazetta's Warren covers provided that company with a visual standard that provided a boost to its general newsstand presence, and took Frazetta's name and visual impact to mom and pop store magazine racks coast to coast.

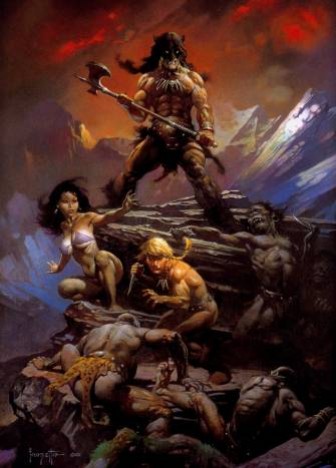

There was a second major component to Frazetta's creative and professional rebirth in the 1960s: paperback covers. Encouraged by Roy Krenkel to try providing art for paperback books, Frazetta began to take on gigs at Ace Books. Starting with Tarzan covers and an assist by Krenkel, this soon expanded into a full-time job providing painted covers and occasional interior illustrations to a number of Edgar Rice Burroughs paperback series and related genre works. The Frazetta paintings sold books all by themselves, and if any of the characters seemed slightly off-model in terms of what the books might describe -- Frazetta wasn't reading them, and wondered out loud how many people were -- nobody seemed to care. It was as if the artist had reached back to moments of high illustration craft that were common in visual media in the 1920s and 1930s and employed them solely in portrait after portrait of vigorous men, savage beasts, inclement weather, the occasional powerful, foreboding female figure and scores more soft-looking, bosomy maidens sporting fleshy buttocks that all by themselves were an effective argument for a type of beauty that ran in the opposite direction of that decade's more androgynous fashion icons. It was impossible not to feel grateful for the work in addition to slightly overwhelmed. His paperback cover-painting career is probably most firmly linked to a certain physical conception of Conan The Barbarian that envisioned him as a hard man but not an overly muscled one: a stone cold, stone-age killer.

It was an older client that changed Frazetta's life. His portrait of Ringo Starr in a mock advertisement for "Blecch Shampoo" moved him out of making comics and more fully into making painted images, a place he would stay for the remainder of his professional life. It directly led Frazetta to his first gig doing a Hollywood movie poster, for the Peter Sellers film

What's New Pussycat? He dove into this lucrative profession in typical Frazetta fashion, making poster art for a slew of films for the next seven or eight years, including

The Secret Of My Success,

The Busy Body,

The Fearless Vampire Killers,

The Night They Raided Minsky's and

Mrs. Pollifax.

As the 1960s became 1970s, Frazetta the painter started to accumulate enough work in enough high-profile showcases that he started to become Frazetta the brand. Frazetta's career was firing on a number of cylinders, a combination of mainstream gigs like the Hollywood posters (his last before his own

Fire and Ice was a much-publicized poster for the Clint Eastwood/Sondra Locke effort

The Gauntlet); an almost grassroots effort that involved connecting with fans of his paintings through portfolios, prints and books; and using the accumulation of prestige in all corners as a way to facilitate the sale of original art to collectors of both the status-seeking and genuinely-touched variety. The rising heavy metal music world picked up on the boldness of Frazetta's fantasy imagery and his work ended up appearing on a number of album covers, perhaps most famously southern rock outfit Molly Hatchet's 1979

Flirtin' With Disaster album, that made use of the painting

Dark Kingdom. It was that group's biggest hit, and the gothic excesses embodied in such covers were both a part of that aspect of the music scene and an element against which pushed later pop music scenes and movements.

The

New York Times reported in 1977 that a single volume containing multiple reproductions of his work,

The Fantastic Art Of Frank Frazetta, sold 300,000 copies for Bantam in its first two years on the market -- a hit by any standard and an almost unfathomable one for a book of pulp art paintings. That book would continue to be sold and reprinted well into the 1980s. Frazetta enjoyed other book successes over the years. The best single volume was likely 1994's

Frank Frazetta: A Retrospective, published by the Alexander Gallery as a stand-alone but as a catalog for their showing of the painter's art. Its high-end production values have made the first edition a book worth multiples of its original low three-figure price.

The verve of and general success enjoyed by Frazetta's work hadn't gone unnoticed by younger artists, and he remains a popular touchstone for anyone that wishes to combine fantastic subject matter with western painting tradition. A slew of popular artists such as but certainly not limited to Jeff Jones, Gerald Brom and Boris Vallejo, inspired to varying degrees by Frazetta's work and professional example, began to find work of their own starting in the early 1970s, and the number of artists with at least some Frazetta influence has grown in every decade ahead moving ahead. While the level of fealty some displayed for Frazetta's work might bring accusations of their riding the artist's coattails or simply providing an inferior version of what Frazetta did well for an audience that frequently wishes for more of something somewhat related to an original if no more original is to be had, the sheer number of artists who found at least some inspiration from Frazetta has meant that his approach to fantasy imagery has retained currency above and beyond the direct impact of his own work. Long before his passing, Frazetta's spirit haunted the science fiction and fantasy sections of most mainstream bookstores. While not everyone knows Frazetta's name, there are very few literate adults that won't recognize him according to his general artistic approach and subject matter if described in a few words.

In the early 1980s, Frazetta collaborated with animator and director Ralph Bakshi to produce an animated film based on elements of his work.

Fire and Ice opened in the US in August 1983 on approximately 90 screens and in various markets around the world for the next three years. Its domestic box office total was $760,883 according to

Box Office Mojo. It has enjoyed a haphazard critical reputation over the years, although it seems to fare well for those looking to an alternative to Disney and anime styles that don't balk at the film's use of rotoscoping, or drawing over actors. The film is at its best capturing the physical action of its actors/characters, feats sometimes worked out on set by Frazetta himself according to the Groth interview some years later.

Beginning in 1986, Frazetta experienced the first symptoms of a debilitating thyroid condition that he spent the next eight years fighting, along with a related 50 pound weight loss (to 128 pounds) and massive amounts of anxiety. In the 1994 interview with Groth, Frazetta cited a massive workload and exposure to inexpensive chemicals in various work materials as a potential cause. He also indicted much of the art from this period as lacking the verve of work before and after.

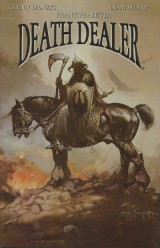

The Frazetta name also made several minor, sporadic comebacks into comic books over the last 25 years.

Fantagraphics published two comic book-sized collections of Frank Frazetta comic book material in 1987 as

Frank Frazetta's Thun'da Tales and

Frank Frazetta's Untamed Love. Then-Fantagraphics rival Kitchen Sink Press published some of the artist's humor work as

Small Wonders: The Funny Animal Work Of Frank Frazetta in 1991. A reasonably high-profile series featuring Frazetta's Death-Dealer character

appeared from Verotik in 1995; those books featured Frazetta paintings as covers and involved both Vertotik's founder Glenn Danzig and two Frazetta-influenced artists,

Simon Bisley and

Liam Sharp, in various creative roles. That series ran five issues at a point at which the North American comics industry was beginning to fracture badly especially for anything not a recognizable superhero comic. That series informed or at least prefigured a more ambitious, interlocking series of comics from Image starting in 2007. Bearing Frazetta's name and based on a number of iconic paintings, series and one-shots released to date include

Frank Frazetta's Death Dealer,

Frank Frazetta's Dracula Meets The Wolfman,

Frank Frazetta's Moon Maid and

Frank Frazetta's Neanderthal. Those comics again featured Frazetta paintings as cover with the interior duties coming from younger writers and artists.

The Frazetta's opened a small museum on their East Stroudsburg, Pennsylvania property in 2000, which quickly became the focus for the artist's ongoing projects and the starting point for establishing his artistic legacy. Lance Laspina's 2004 DVD release of his

Painting With Fire documentary brought new attention to the Frazetta, and a glimpse into their life at the time of filming starting in 2000. It was generally well-reviewed.

Frazetta continued to paint throughout. He would expand the number of images enjoyed by certain Frazetta icons, such as the Death-Dealer, and work in a wider variety of fantasy settings, from the soldiers in

Seven Romans to the almost science fiction-looking

Sound. In the early 2000s, Frazetta suffered a series of small storkes that caused him to relearn to draw with his left hand. There were eventually rumblings late in his career that like many older artists Frazetta continued to work on older paintings that many thought could suffer due to the time passed, a drop in facility, and the potential lack of connection between the aims of the older artist and his younger self.

Ellie Frazetta

passed away on July 17, 2009 after a year-long battle with cancer. She was rightly memorialized as not just Frazetta's life partner but as a savvy managerial presence who managed to raise both the artist's profile and the money he was paid for art gigs and original work. Following the loss of the family matriarch, the Frazetta children began to fight over custodial matters regarding their aging father and his impressive estate. This boiled over into public view in December 2009, when Frank Frazetta Jr. was arrested after trying to break into the East Stroudburg museum, maintaining that he had his father's permission to move some of the work to a safer location. Those 90 paintings had an insurance value of $20 million. Just last month a statement from the family said that the conflict over the work had ended due in part to the insistence of Frazetta. The criminal charges were subsequently dropped. It is no small note of encouragement that this arrangement was reached before the passing of the artist.

It's hard to grasp the overall impact of Frazetta's long life and prodigious career. He had enough credits and displayed enough skill early on that he might be considered a forgotten Golden Age Great if his career had stopped the moment he left Al Capp's studio. There are a couple of massive What If? moments that took place in the early '60s. If DC hadn't been so rigid in terms of its approach to house style and someone smart there had seen Frazetta's work as grounded in the same Dan Barry take on adventure comics that drove a lot of their books even then, he could have been an astonishing high-workload, high-craft freelancer and provided them with another Joe Kubert-type anchor for their line as Marvel surged. Or he could have become as

the cartoonist Sam Henderson suggests a valuable contributor to

MAD in its soon-to-be sales heyday, with all the attendant freelance illustration work that likely would have come his way.

As isn't the case for many people in comics, Frazetta's roads not taken

aren't the happier story; he accomplished almost three careers worth of work in his busiest decade, and stayed as productive as possible after that. He kept the important rights to his work, profited for that resolve, and connected with fans like almost no other visual artist of the 20th Century. Frazetta's attention to fundamentals of craft, his dominant influence on a field of illustration that is likely to continue for decades yet and his relationship with iconic figures in an entire sub-school of popular literature, provide ample opportunity for children born at any time over the last 60 years to experience his work in a meaningful way.

Coming across his work in the 1960s and 1970s, amid those decades' absolute disconnect from the recent past and outright suspicion of junk culture, was a specific revelation for their being so very little out there like it. Frazetta's work was one of the few consistent, visually accomplished gateways to somewhere else, a way of escape available to a generation of kids that was psychologically preparing to die when someone set the skies on fire. Frazetta's were potent images, strange, of obvious skill and stuffed with conflicting messages. There were the soft women and the more dread, powerful ones. Men faced off against monsters but also nature, and in some cases their own savage impulses. There was light like the light we were used to but also strange colors, light like no one had seen but that Frazetta somehow understood. They weren't

inviting fantasies, but formidable ones, foreboding, aspirational rather than something that coddled or flattered you. If you went through the wardrobe into Narnia, events would likely fall into place, and you were pretty sure you could've handled that ring, but if you went to one of the worlds Frazetta painted something was going to eat you or stab you or have your soul. These were fantasies you steeled yourself towards rather than fell into. And so it was with Frank Frazetta's art: it frequently impressed, it almost always inspired.

Mr. Frazetta is survived by three sisters, two sons, two daughters, and 11 grandchildren.

*****

*****

*****

posted 11:00 am PST |

Permalink

Daily Blog Archives

November 2019

October 2019

September 2019

August 2019

July 2019

Full Archives