October 21, 2012

CR Sunday Interview: Julia Wertz

CR Sunday Interview: Julia Wertz

*****

Julia Wertz turns 30 later this year, which seems to me an excellent time for any cartoonist to release their best work to date.

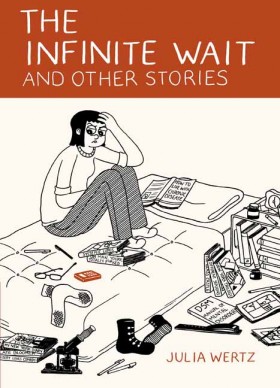

Koyama Press' new

The Infinite Wait And Other Stories offers up three stories about the young cartoonist's life: one about her being diagnosed with

lupus, one about her hometown library and one about her vocational history. Wertz's comics have always been funny, but in these stories we see a bit more of a formally restless comics-maker: plopping her jokes wherever she likes on the page, taking what might seem like long digressions into side-issues and stand-alone anecdotes, structuring entire sequences around a visual memory to match her facility with remembered dialogue. I liked it quite a bit, and I've been intrigued by some of the things which she's written and said through her comics about working with smaller publishers after her time working with bigger ones. I'm happy Julia took some time away from doing things in support of the new book to talk to me. At least two of those things are forthcoming: she's appearing with

Nate Bulmer at

Desert Island on November 15 and will be in conversation with

Ellen Forney at

the Strand on Nov 19th. You should go. -- Tom Spurgeon

*****

TOM SPURGEON: I know that you attended SPX, and that you said on your site that you were doing some work on packages for the book that are going out to people that buy

TOM SPURGEON: I know that you attended SPX, and that you said on your site that you were doing some work on packages for the book that are going out to people that buy Infinite Wait from you directly. I wondered how much of that stuff overall you have to do for a release like this one?

JULIA WERTZ: You mean like all the packaging and stuff?

SPURGEON: Yeah, that. I also wondered how many shows you end up doing, how many signings. For that matter, how much do you feel comfortable

doing?

WERTZ: The way that [Koyama Press Publisher] Annie [Koyama] and I did this book is that instead of getting royalties she just gave me a set amount of free books that I then sell. So it's a whole lot of... I'm actually packaging stuff right now. It's very tedious: a lot of sitting around and making keychains and signing books. It takes a couple of weeks to get those orders out.

All I did was SPX for this book; I'm not going to

APE or anything. I don't know, I feel like I could be doing more shows. I'll be doing a book release thing, and then I have this conversation with -- you know Ellen Forney?

SPURGEON: Sure.

WERTZ: I'll be doing a conversation with her at The Strand.

SPURGEON: What was appealing to you about doing the free books vs. royalties deal with Anne? Was it that you have a sense of your personal audience, an audience that you could reach independent of a publisher, that it was more profitable to pursue that audience this way?

WERTZ: Doing this kind of deal, I was able to get more money because I put together package deals: keychains, hand-drawn panels, mixed tapes, sales that wouldn't exist if I just received royalties. There isn't much, if any, money in small press so you have to find other ways to make it work.

SPURGEON: You've talked about moving to a small publisher in various places... in a very positive way, that you're very happy to be working with people at a smaller press. The book is dedicated to Dylan Williams, and you're working with Anne. Dylan was and Anne is a very positive force in that world of small-press books.

WERTZ: They're into their artists. They're into their artists making money and getting the recognition and the benefits of their work, as opposed to a big publisher where they're all about, "How can

we make money off of this?"

SPURGEON: Now is that something you personally react to, something where you think this makes them better people and you'd rather work with them? Or is it more about how you prefer to work? Because I have a hard time imagining you as someone who might get bruised rubbing up against the crassness of big publishing. Is that you just have distaste for that kind of profit motive?

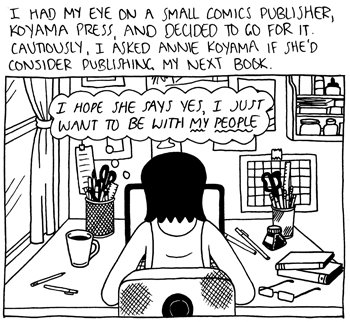

WERTZ: Yeah. I wrote about this in the book. With the big publishers I said I wanted to do a book about having lupus and they said, "That's not mass-marketable." And they wanted to see a proposal by me. So that didn't sit well. They also don't table or anything, so they just sort of put the book out and that's it. I would end up spending my advance money on travel and tabling and it did not work out. It feels cold, because they don't care about it at all. They don't have any investment in the book once it's published other than whether it sells or not.

I decided to take it to Annie because I really like what she's doing with Koyama. She's very artist-positive, and she shows up for them and she tables. It was more of a personal decision. Also she liked the idea of doing a story about lupus as opposed to being, "That's not going to sell." She never thinks about what sells or what's going to sell. That's really not something that's on her agenda. You know how it was, that there was a bubble where all the cartoonists were getting big publishing deals and that bubble sort of burst. I think it was good. We all went back to where we belong, which is small press. These indy comics aren't mass-marketable. I just feel it's sort of good to be with my people again. These are people that are going to care about the work.

SPURGEON: This is an aside, but it strikes me as weird that anyone would think lupus isn't mass-marketable. So many people have systemic, connective-tissue diseases. Who doesn't know someone that has lupus or scleroderma or something along those lines? That's bizarre to me.

WERTZ: It makes no sense. They estimate that there's two million people in America with it. Auto-immune diseases in general... I mean, you can even group AIDS into that if you have to.

SPURGEON: Now will you get any attention on this book for the subject matter, do you think? Are you interested in receiving attention from people that have those issues themselves?

WERTZ: I would like that, but it's not as much of a thing I want. When I talk about my drinking problem, I really want the people that have the same problem to read that. This one is not so much where I want people to connect with it -- I do get e-mails that say, "Yeah, I went through the same experience and it's really nice to see someone joke about it on paper. It's so horrible when it's happening."

SPURGEON: One more thing about working with publishers of different size. You've written about this in the book, and in some of your pieces outside of the book; I think you wrote something after a Minneapolis show that was very positive. When you joke in your introduction along the lines of this kind of working relationship satisfying your "not the boss of me" impulses, it made me wonder: do you think working with the book publishers was having an effect on your art? Will your work be different moving forward in part because of how you're publishing?

WERTZ: Yeah. Yeah, definitely I think it was affecting my work. As soon as there's a lot of money and a lot of prestige involved I caught myself leaving certain things out. With comics you kind of veer into a very weird avenue or just things that don't read well to them. They don't like books that don't have a conclusion, that aren't really about anything. Short stories are very hard to sell.

I caught myself... there was one story where I wanted to get a little bit meta with it: put a diary comic in it, so it would be a different style. The editor said, "This is going to confuse people; just stick to your style." I definitely caught myself tailoring it to a larger audience. I don't want to work that way. Even though I could do what I wanted, it's a mental block that I have to work differently to sort of please them.

Also during the time I decided to do this book with Annie was when I was dealing with a Hollywood deal that I ended up killing because of this reason. I just came to the conclusion that even thought it's not financially beneficial for me to work this way, so independently, it's not worth the money for me to be miserable for it to affect my creativity. That's the one thing I want to have control over at all times. If having money in it is affecting it, I don't want to do that. Even if it might be a smart career move, I just don't give a shit. [Spurgeon laughs]

SPURGEON: Do you worry about the other side of it, though? Maybe you have a low opinion of the kind of support you got, but do you worry about not being able to work with an editor, not being able to get that kind of feedback, not having your art develop through the kinds of resources that you may not have access to working with a small-press publisher?

WERTZ: Yeah.

SPURGEON: Do you pull in your friends to get feedback that way?

WERTZ: I should more than I do. Especially because there are some errors in

The Infinite Wait that we did not catch. I guess it would be nice to have more professional people on top of it, I guess? [laughs] I will get help from friends to get that feedback. I feel that one of the big-publisher editors I had didn't give me the kind of feedback that was even helpful. Once she took a page and actually circled a punchline and wrote in the margins, "Can you make this funnier?"

SPURGEON: Oh my god. [laughs]

WERTZ: That made me so angry. I called her and I was like, "Don't ever tell me how to write a punchline for a comic." This person didn't know comics. Their editing doesn't help me with the comics; their editing is more like does it make sense to an average

Barnes & Noble reader who wants a story that has a beginning and a middle and some sort of satisfying, wrapped-up end.

I don't really work with people who give me feedback on it, because I just want to do what I want to do. Working with a small press means that it won't reach a larger audience. I won't break through that ceiling -- I don't know if that makes any sense. You can only go so far in comics, and if I stick with small publishers it will be harder to break through to a large audience unless I did some kind of TV deal.

SPURGEON: One thing I liked about this work is that it does seem like you're pushing at some things. The way that you structure some of your jokes seems different than the way you've done things in the past. There's an assuredness to it: you seem confident in the writing of it, and where the humor is.

SPURGEON: One thing I liked about this work is that it does seem like you're pushing at some things. The way that you structure some of your jokes seems different than the way you've done things in the past. There's an assuredness to it: you seem confident in the writing of it, and where the humor is.

WERTZ: Well, thank you.

SPURGEON: My point is I wouldn't dare tell you how to tell a joke at this point. You know how to tell a joke. I wondered, though, how precise you are with the writing. Humor can very difficult; it can rely on a degree of precision. How much is it just natural for you to make something funny on the page, and how much is what we see something you really worked over?

WERTZ: With this one... you've read my earlier work, so you know how it was set up in four panels to be 1, 2, 3, punchline. That was very easy to do. With

Infinite Wait I kind of throw the punchline in the middle of the page. It's actually easier that way because that's the way natural dialogue happens. It's not at the end and then the conversation's over. That's how I'm going to work from now on. I'm not going to do any of that punchline stuff.

It's not really that complicated. When I'm going through times in my life that I know I'm going to turn into a comic, I write down all conversations I have that I think are worth remembering. In this case I had drawn this comic out many years ago in stick figure form. So I was basically recording dialogue how it is, how it is in real life. It's actually pretty easy.

SPURGEON: How did you land on that process? I know with playwrights, sometimes in an early class they make you record conversations and write them out. Your way of doing it sounds like it may have developed more naturally. Was it just your desire to want to be able to capture elements of dialogue, or are you a compulsive recorder of what's going on around you?

WERTZ: Half of it is compulsive recording. Actually, I have a very good memory for dialogue. It's a little bit creepy. I can recall conversations I had years ago, like verbatim. I think that that's just a natural skill, I guess. Maybe it's helped by recording and knowing I should remember something. But I don't know, I can remember conversations I had as a teenager word for word, so I think that's just sort of a natural thing.

SPURGEON: So what ends up on the page? How refined is that? There's a big difference between recorded dialogue and dialogue for the stage, to continue with that example. For the comics, do you play with the dialogue? Or is it pretty much naturally as you remember it?

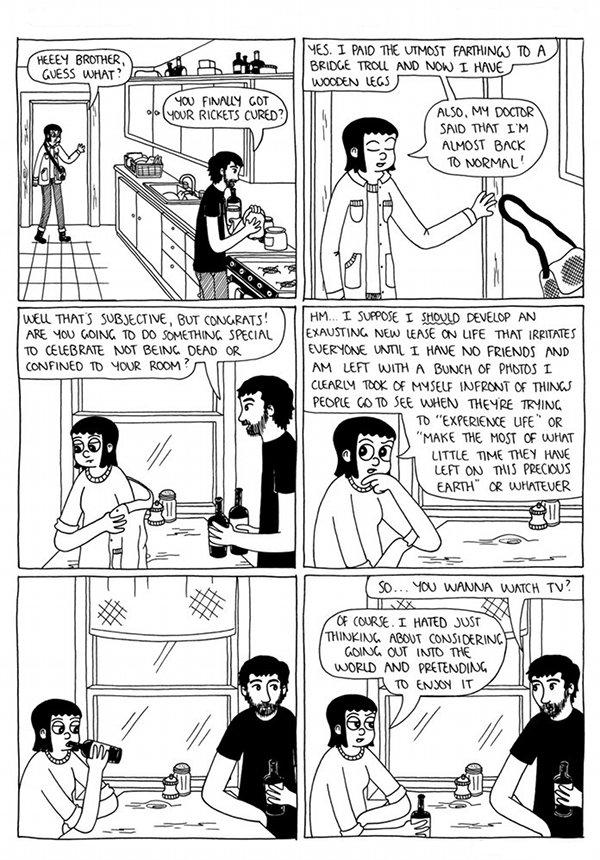

WERTZ: I'll work on it a little bit. Sometimes I'll have said a joke way later. And I'll be like, "Oh, I should have said that." A lot of conversations with my brother we would have over text messaging, and then in the comic I turned them into face to face because reading three pages of text messages does not make any sense. [laughter] I'll take conversations that happened over a week and put them into one afternoon. In that way, I sort of manipulate time and conversations. I'll take snippets of conversations and act as if they happened in an hour. There's a little bit of poetic license, I guess.

SPURGEON: You're my new favorite interview subject, because you're anticipating all my transitions. [Wertz laughs] The stuff with your brother: I think those scenes are pretty great. There's an intimacy to your conversations, an easiness to your conversations, to the point I wonder how important it was for you to nail down a distinctive voice for your brother, to make it his own? My impression is that what you did was very subtle but I thought you nailed that, that you got the shared intimacy, the shared language, while at the same time his voice was different than yours. He's a very appealing character in the book, too, as a result, I think.

SPURGEON: You're my new favorite interview subject, because you're anticipating all my transitions. [Wertz laughs] The stuff with your brother: I think those scenes are pretty great. There's an intimacy to your conversations, an easiness to your conversations, to the point I wonder how important it was for you to nail down a distinctive voice for your brother, to make it his own? My impression is that what you did was very subtle but I thought you nailed that, that you got the shared intimacy, the shared language, while at the same time his voice was different than yours. He's a very appealing character in the book, too, as a result, I think.

WERTZ: I'm totally happy to hear that. It's a little bit tricky, too, though, because my brother and I, I've had friends say that if you transcribed your brother's and your conversations you would not know who said what because we have exactly the same sense of humor and have the same things we joke about. I tried to make him a little bit more dry, which is absolutely how he is. He's very good at insulting me. It was a little bit tricky because we talk the exact same way. I didn't want it to appear as if I was putting punchlines in his mouth. All his punchlines, they're all things he said in real life. Sometimes I do think it sounds a little bit too much like my character, but that's what happens, so that's what I went with.

SPURGEON: I got the sense that he was a distinct character; I just wasn't sure how you got there. It sounds like you work on it. You applied your writing skills and it came out that way. [laughs]

There's a basic question I wanted to ask, that comes out of writing for yourself, writing autobio, writing about things that happened to you. Your comedic character is very different than a lot of cartoonists' stand-ins. There's not a lot of working out of your neuroses. It's a very strong character. You're more Groucho Marx than Woody Allen. There's something heroic to the character that you're being funny all the time, and constantly killing it with humor. It's not just a funny character, it's a strong character, and I wondered how aware you were of that.

WERTZ: That's something I've really not considered too much. I would assume it's a reflection of myself. There are definitely things I don't work on because I'm just talking about myself. I tend to handle things in real life maybe with more humor. I'm a little bit more blase about things in real life because that's my defense. I think that comes out in the work. I will try to make my character not look too much like she's using it as a defense. I want to have the moments of humanity in there. I wonder if there's a little bit more mopey scenes. In the one I'm working on about trying to get sober, there's a few more of those. It's a little bit less jokey; I don't want that to be my gimmick: "this person clearly has a problem where they can't deal with anything without making a joke about it." So I'll probably veer away a little bit. But because that's a natural response, that's how my work comes out.

SPURGEON: In one memorable scene in this book, you talk about your discovery of comics. One thing I think interesting about how you describe it is that you had a reaction to the experience of comics themselves, the impression of the words and pictures together and how you were able to read it. That strikes me as an intriguing reaction, and maybe not one I'd guess for you. I could see you responding to the personal expression aspects of it, but it seems you also had a reaction to the medium itself.

WERTZ: It was a very instant and positive reaction. I also don't think that's too common in comics because most people grow up with comics. It never hits them over the head like that. I had never seen that kind of graphic novel before. So it was so instant. I loved it immediately, and I'm not really

into things. It takes a lot for me to be into something, but I don't know, right away I knew -- I didn't know I wanted to do it, but I knew this was a thing I was going to be obsessed with for a while.

SPURGEON: Can you describe what it was about the experience, the visual impression you were getting? Was it getting that kind of information visually? Was it the range of expression that the artists were able to get for mixing the prose and art?

WERTZ: A lot of it had to do with just the way that they drew.

Julie Doucet's and

Will Eisner's artwork. I didn't know that comics could be that kind of artwork; I was only familiar with

The Far Side and

Calvin and Hobbes and

Garfield. Then they had these really detailed drawings of the city… or of their bedrooms. You know how Julie draws her bedrooms? I had no idea that the art could be that pleasing. I could spend all this time looking at it.

I didn't understand before that there's a connection to the writing with that kind of artwork -- it fills in the blanks. The kinds of comics I was reading before, they don't fill in the blanks: they complement the text. That's how newspaper funnies work. I had no idea they could be so interconnected, that looking at the artwork could be like reading between the lines of a story. I just didn't know you could tell stories like that. Where a lot of it is silent. I think that's what really connected with me, because I had never seen that before.

SPURGEON: You have a very direct art style. How do you feel about the visual side of what you do in terms of communicating the same things that Eisner or Julie were able to? Do you think it has something of the same effect?

SPURGEON: You have a very direct art style. How do you feel about the visual side of what you do in terms of communicating the same things that Eisner or Julie were able to? Do you think it has something of the same effect?

WERTZ: I hope it does. I definitely try to make the artwork tell parts of the story as opposed to just being complementary. I also know that I have a lot of limitations as an artist. I'm not as good as the average person working in comics. They did their art first and then came into comics storytelling, where I did it in reverse.

I may have talked about this in the first interview we did, where I choose to do it simple because that's the way people connect to it, they can project themselves into it more than a very detailed image, which separates the artists and the reader feels that they're looking at an artist's interpretation of something as opposed to putting themselves to it. I think that my lack of artistic skill can be of benefit to the work itself in terms of progressing the story.

SPURGEON: I wonder how you feel about it now, though. When my friends and I talk about your work -- because we're nerds, and we talk about people's work [Wertz laughs] -- one thing that seems to come up with people that are mostly complimentary of your work as well as those that are critical of what you do is that the direct style you use works very well with the humor that you do: that you can get right to the joke, and it allows people to project themselves into a situation. Now you're engaging these subjects with a lot of nuance, stories that even refer to other stories and past work you've done. People wonder if your art can communicate those elements as effectively as it allows us to see Julia slaughtering people verbally. As you engage more themes, do you think about developing your work to better encompass those things you wish to engage in your comics?

WERTZ: Yeah. I hadn't really thought about it. But I guess the more complicated the work gets, the more complicated the art style gets... I don't think that was a conscious decision. I think that was me developing as an artist and wanting to put more time into the artwork. I've been debating working for my next on maybe not putting the more detailed backgrounds from

The Infinite Wait, more detailed than previous work. I wonder if I should not do that, not only to save time, but also I feel it gets a little repetitive and distracting. That just might be more of a personal decision, though, not so much a conscious one.

SPURGEON: What element of the visuals do you think best reflects where you are as an artist?

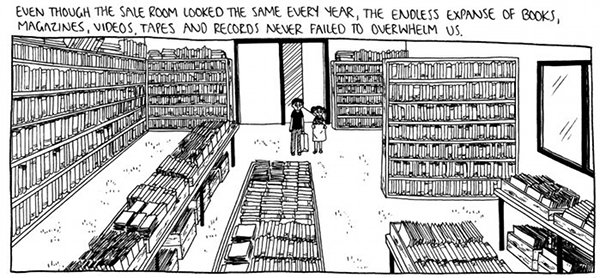

WERTZ: I think it's in those backgrounds where it comes through. I'm terrible at drawing people, but I think I've become good at drawing simplified versions of the backgrounds. Not so much the artwork but I like what I did with the artwork in the short story about the library. There are a lot of books; it helped create the environment.

SPURGEON: The library story shows off another strength of yours, something we've talked about maybe a bit in terms of dialogue, that you have this very specific string of memories -- the alcove where you can fit under, for instance. I think that's a strength of your work overall, that your memories of moments and places are very pointed, very exact. Do you have a similar gift for place-memory?

SPURGEON: The library story shows off another strength of yours, something we've talked about maybe a bit in terms of dialogue, that you have this very specific string of memories -- the alcove where you can fit under, for instance. I think that's a strength of your work overall, that your memories of moments and places are very pointed, very exact. Do you have a similar gift for place-memory?

WERTZ: Yeah. It's not as strong or persistent as the dialogue memories, but when I have something from my childhood that had a visual sensation, I can very easily recall it in my memory. I have memories from early childhood when you're really not supposed to have memories. Those memories are very visual: the pattern of a couch or the pattern of a dress that I sort of took a picture of and then remember it for forever. If it was something I was obsessed with, like a secret hole I could hide in -- which I have a lot of -- that just stuck with me and I would try to draw it verbatim as I remember it.

SPURGEON: Was the library story always supposed to go last in the collection? The introductory material makes me think it might have been intended for second.

WERTZ: Actually, now that you've said that I feel like it was an accident to go last. I should have put the short story in the middle to break up the two long ones.

SPURGEON: I hate to talk about "next," but you mention in there that there's work that you haven't published yet that seems like it was important to your development.

WERTZ: The book that's coming out next I actually drew the whole thing, I drew 220 pages of it. I did that before I did this book. I'm going to trash it and re-do it.

If I do this book; I haven't made up my mind whether or not I'm going to do it. The stuff I reference as unpublished in that book is childhood stories that I haven't had time to really work on. I've maybe drawn six pages of it. I have a lot of that stuff, where it's just random pages I want to work on. I've got that whole beast of a book that's just sitting there.

SPURGEON: I wondered in general how much work you do that doesn't get used. I've wondered that about people that post stuff on-line generally, but you specifically.

WERTZ: Well, there you go. I have a whole book. The year and a half I worked on that I'm going to flush down the toilet.

SPURGEON: The work or the personal experiences as well?

WERTZ: Just the work. It's good that I did it, because I have something to work with as opposed to just starting the book blindly. It does mean that I just spent a year and a half on artwork I'm not using.

SPURGEON: Something I wanted to build on when we talked about your character being different. There are a bunch of stories in here that touch on class. Some of it is overt: the material about the jobs you have, and waiting on rich kids in the diner. But also seems like class informs your work more generally. When most autobio cartoonists talk about being broke or not having a ton of resources, it seems like it's coming from a different place than where you're coming from. Do you feel there's a difference?

WERTZ: I think what you're getting at -- tell me if I'm wrong -- is that when cartoonists talk about being broke, it's a self-inflicted thing. You don't

have to be a struggling cartoonist. You can just get a fucking job. [Spurgeon laughs] It kind of irritates me. That whole aspect of, "I'm so poor; I just want to do my artwork." Not everyone can make money from their artwork. That's a very privileged thing to be able to do, that even if you're a great artist you can't always achieve. So sometimes you just have to nut up and get a job. The stuff that I was talking about in

Infinite Wait, that came from a childhood of not having money, and growing up poor in a very rich town. I had no control over that financial situation.

SPURGEON: Do you think that has an effect on your decision-making now? You talked about not pursuing things that might be better for your career; do you think your unique perspective allows you to make stronger decisions?

WERTZ: Yeah. When you don't grow up with money, it's never of great importance. It's never a goal. I've always just wanted enough money that I could live the life I'm living now. I live alone, which is great. I don't need a whole lot of money to do what I do and be happy with it. Making money was never really a goal. When you grow up without money, you never assume you'll have it. I feel like I have it in the sense that I live the life I want to live. I don't need any more. That's why I'm able to turn down opportunities that might be more lucrative because I'm happy with where I'm at.

SPURGEON: Is it weird to take that kind of stand in public? I remember when you posted the strip about turning down the screenwriting/television work, people were hectoring you about this specific personal choice you'd made. I couldn't believe that people thought they had a vote. Have you become accustomed to that aspect of it, that people think they get to weigh in on what you're up to?

SPURGEON: Is it weird to take that kind of stand in public? I remember when you posted the strip about turning down the screenwriting/television work, people were hectoring you about this specific personal choice you'd made. I couldn't believe that people thought they had a vote. Have you become accustomed to that aspect of it, that people think they get to weigh in on what you're up to?

WERTZ: Yeah, I mean [laughs] that's the problem with the Internet, that people think they do get a say in your life and the way you live it. When I turned down that deal, a lot of people, they were like, "You're an idiot." [Spurgeon laughs] When you're not a creative person, if you're just someone that views the creative world as a spectator, you sort of assume that everyone's ultimate goal is to go to Hollywood and make that kind of money. That was never, ever my goal. It wasn't something I even thought of until it was right in front of my face. It wasn't something I was striving for, so it was very logical for me to turn it down when it wasn't what I wanted. People from an outside point of view don't understand that's not everyone's goal. Even people in the TV world were totally baffled why that wasn't my goal. "Isn't this what all artists want? Look at all this money we're going to give you. This is what you wanted since forever." The fact that I didn't want that, it's just confusing to a lot of people, I think.

SPURGEON: How typical are you in your peer group, maybe not this specific decision but more generally? You talk in Infinite Wait about the Pizza Island experience. Are you guys all going through these kinds experiences? Are you typical in terms of how you and your friends are processing these issues?

WERTZ: Yeah, definitely. I think so. When I was in Pizza Island, three of us were working with big publishers, and we all got dropped at the same time.

Lisa [Hanawalt] is doing a book with

Drawn and Quarterly. We're all in the same boat of getting back to working with our people and being really happy with us. There's a lot of discussion. I spent time in Minneapolis talking about Koyama and

Tom K's Uncivilized Books, and

Spit and a Half Distro. It's very exciting. I think we're happy to be in the same boat, working with less, I guess.

SPURGEON: And does that make that decision easier, having other people around making those decisions? You talked in Infinite Wait

about suddenly discovering you had fellow travelers, an artistic peer group.

WERTZ: Yeah. We can definitely talk about it. Oh, we shit-talked so hard and that's always delightful to be able to do that with people at the same sort of level. I don't feel like I'm flying blind here at all. It's definitely a comfort.

*****

*

The Infinite Wait And Other Stories through Julia Wertz

*

The Infinite Wait And Other Stories through Secret Acres

*

The Infinite Wait And Other Stories at Koyama Press

*

Museum Of Mistakes

*****

* photo of Wertz taken at SPX 2012

* cover to the new book

* images from the new work hopefully used so well that there's no question as to why they're being used

* end image from the work (below)

*****

*****

*****

posted 6:00 am PST |

Permalink

Daily Blog Archives

November 2019

October 2019

September 2019

August 2019

July 2019

Full Archives