September 12, 2012

CR Sunday Interview On A Wednesday: Tim Sale And Scott Hampton (2010)

CR Sunday Interview On A Wednesday: Tim Sale And Scott Hampton (2010)

*****

It was my great pleasure to talk to

Tim Sale and

Scott Hampton in 2010 at Charlotte's

HeroesCon on the subject of painting in comics. The conversation took place shortly after

the passing of Frank Frazetta, so we started with a discussion of his work and legacy -- actually we start with a discussion of hotel-related convention emergencies, but we get to Mr. Frazetta pretty quickly. We also spent some time tracking each artist's attitude about their respective professional journeys. That's the heart of what I wanted to talk about, and that's what the small but very respectful audience got.

Tim Sale is one of mainstream comics' premiere illustrators of the last 20 years, with a dozen or so major projects to his credit;

Scott Hampton is an enormously skilled painter -- and artist more generally -- who was present from the very beginning of this extended, current era of paintings employed in genre comic books. They're not the kind of comics-makers to whom I generally get the chance to speak, so I was grateful for the opportunity presented by the convention. I remember it as fondly as I remember any panel experience. Both men were super-nice, and I thought very articulate. I hope I get to chance to speak to both artists again, together or separate.

You can listen to this conversation

here. You may notice if you listen to that that I tweaked a bit for this record from my recording. I just sort of do that naturally, now, so I apologize if anyone finds that disconcerting. I think theirs is slightly longer, too. -- Tom Spurgeon

*****

TOM SPURGEON: One thing that occurred to me coming into the weekend -- Tim, I read your writing on the subject, as a matter of fact -- is that we just lost one of the greats in terms of painting and also in terms of comics in Frank Frazetta. He's an iconic figure for fantasy culture and recognized as one of the significant visual talents of the 20th Century. Tim, I was intrigued by what you wrote about his legacy, how that legacy might develop and how his comics legacy is different from his painting legacy. Tim, I was wondering if you could talk about those thoughts, and Scott, if you could tell us what your thoughts were when you heard that one of the great comics talents and visualists had passed away.

TOM SPURGEON: One thing that occurred to me coming into the weekend -- Tim, I read your writing on the subject, as a matter of fact -- is that we just lost one of the greats in terms of painting and also in terms of comics in Frank Frazetta. He's an iconic figure for fantasy culture and recognized as one of the significant visual talents of the 20th Century. Tim, I was intrigued by what you wrote about his legacy, how that legacy might develop and how his comics legacy is different from his painting legacy. Tim, I was wondering if you could talk about those thoughts, and Scott, if you could tell us what your thoughts were when you heard that one of the great comics talents and visualists had passed away.

SCOTT HAMPTON: I'll jump in, but first I want to address myself to this business of hotels and emergencies. I was at a show in Chicago, and this was as comics convention, and at two in the morning the fire alarms started going off, saying everyone get out. The thing was, my hotel room itself had a fire alarm inside the room. Not in the hall but in my room, above my bed. Now, if you've ever head a fire alarm go off in the hall, you know how horribly loud they are, but can you imagine in the room, just 12 feet away? [Spurgeon laughs] I levitated six feet. [laughter] I'm in my underwear. My ears are bleeding. I'm trying to get into clothes but I have to take my hands from ear... I come downstairs half dressed. My ears have exploded.

Joe Jusko is half dressed. [laughter] Did you have that experience? [to Sale] You must not have done that show. But my God. I'm the only person I know of that actually had an alarm in their hotel room and I can't explain... you just don't know how loud those things can be until you've done that. I could have sued the place. I look back and I think my hearing is not the best, it wasn't before that, but it's certainly worse now, and I wonder if that might have had some effect. So anyway, I just thought I'd throw that out.

SALE: Be sure to check your hotel room. [laughter]

HAMPTON: Exactly. Exactly. [short pause] Anyway, Frazetta. [longer pause] Tim, you first. [laughter]

SALE: For those of you that don't know, I'm color blind. and so I don't paint. That doesn't mean I can't appreciate painting, and painters. Like so many people, I came to Frazetta through the Conan covers. I couldn't believe it. I'd never seen anything like it. It not just fit Conan it fit so much shit running around in my head that I couldn't do because I can't paint. Just the dynamic aspect of it. The cover of

Adventurer, he's just standing there, but it's just so damn cool. And so powerful. You look at it now, and increasingly -- this is in the '70s, when I... were they published in the '70s?

HAMPTON: '60s and early '70s.

SALE: Okay. It was the early '70s when I saw them. I came to them because

Marvel was going to do

a comic. And so I was like, "Okay." I'd never heard of it before. So I went and picked them up. Loved them. I had an old army coat that had pockets and I carried four

Conan paperbacks with me at all times.

HAMPTON: Brilliant. I love that.

SALE: You never know when you have to wait for a bus. [laughter]

HAMPTON: Exactly. Did you read some of them?

SALE: I read them all.

HAMPTON: Interesting.

SALE: And I liked the stories, too. There was a fight where Conan is pinned and he reaches back and pulls the guy's eye out. And I thought, "Man... that is

cool." [Hampton laughs] It was like a love story in a movie, people start kissing and then you cut to a fireplace and then you're in the next day. This didn't cut away from anything. [laughter] When you're a 13-year-old boy, that was terrific. Frazetta's work was so emblematic of what was going on inside the books, and like I said I'd never seen anything like it. I didn't see any of his black and white work until considerably later. I was in school in New York and I was going to get on a bus because it was what I could afford to come back to Seattle. Seventy-two hours. So I stopped at a newsstand and picked up my first issue of

Heavy Metal and the second Ballantine collection of Frazetta's work.

HAMPTON: Right.

SPURGEON:

SALE: It had a lot of

the Lord Of The Rings black and white work in there. They're great drawings, and very dynamic, the brush work and everything is amazing -- they didn't really fit the book as well his Conan work fit that stuff, but still, as drawings they were amazing. Even after that, kind of working my way backwards, the

EC work and all that.

HAMPTON: I had a very similar experience with Frazetta. I used to dream Frazetta paintings.

SALE: I did, too!

HAMPTON: I had a dream where I walked into a room and there were 50 unknown, brand-new Frazetta originals. And I woke up, and I said, "Oh, I've got to try and remember some of them and put them down." [to Sale] Did you remember any of them? Could you sketch any of them out.

SALE: Yeah. And they sucked. [laughter] With the dreams, I used to do that with

Neal Adams' X-Men stuff. When you woke up what was great in the dream... plus,

I wasn't any good.

HAMPTON: Yeah, yeah. I hear that. I wasn't, either. But still, they looked awfully good. You're making that connection. The thing about being old farts like us, and having grown up and sought out stuff in the '70s, is that because we didn't have access -- there wasn't an Internet, there weren't opportunities to be a click away from seeing everything ever made -- that had its benefits and it had its downsides. Having a lack of access meant that you went hunting. And I went hunting sometimes in old paperback bookshops, and I would find unknown Frazettas and I would find

Jeff Jones paperbacks I had never heard of before. Even at that small size they would blow my mind. So yeah, the era of Frazetta. Frazetta's influence is both broad and deep. And it's a profound influence. Whether you know it or not, you've been inundated. By heavy metal bands. By vans. By clothing. By design work, commercials, work in animation... it's all been influenced by him.

It's a great life. He had a great life, and he's going to be missed. He had a profound, profound effect on the culture.

SPURGEON: I was wondering if both of you could build on an aspect of what was just discussed, the notion of hunting for material -- maybe even in contrast to your formal educations. At the time you were both coming up, and both first doing art, and when you both started doing comics, there was very little in the way of an agreed-upon comics education to be had. You had to build your own sets of influences, and decide what meant something to you and what didn't. I'm thinking that you both had formal art education, but at least one of you if not both didn't finish that art training, and that your comics education might have been totally separate from that. Is that something you had to piece together on your own, an education in comics?

SPURGEON: I was wondering if both of you could build on an aspect of what was just discussed, the notion of hunting for material -- maybe even in contrast to your formal educations. At the time you were both coming up, and both first doing art, and when you both started doing comics, there was very little in the way of an agreed-upon comics education to be had. You had to build your own sets of influences, and decide what meant something to you and what didn't. I'm thinking that you both had formal art education, but at least one of you if not both didn't finish that art training, and that your comics education might have been totally separate from that. Is that something you had to piece together on your own, an education in comics?

SALE: Yes. I was just talking about going to school in New York. I went to

SVA for a year. But the real reason I went is because at the time

John Buscema was teaching a workshop. It was Buscema and

[John] Romita Sr. and

Marie Severin.

SPURGEON: Whoa.

SALE: And they each did a month. Once a week. We'd meet in

the Biltmore Hotel, the ballroom.

HAMPTON: Wow... sounds great.

SALE: There were about 50 of us. Buscema taught anatomy, which is something he was great at. Chainsmoked his way through the whole thing, I remember. [laughter] Romita taught inking and storytelling. Severin pretty much -- and in fact, she was the best teacher -- in terms of serious stuff was the least talented of those artists, but the best teacher by far. She taught covers. Anyway, I did learn some stuff, but not much. I felt very defeated, like it was full of rules that I would never get, and I couldn't feel my way through it. I was homesick and I was 21. I fled New York as soon as I could and went back to Seattle. And I didn't start working professionally until I was 30. By that time I had absorbed a lot of it, but I had done a lot of fantasy work in between. Not comics, but fantasy work. I was looking at all kinds of Frazetta and that sort of thing.

The idea of seeking things out: money to get things, old paperbacks were one thing, but I was talking to

[Joe] Quesada about this a few years ago. When I could start to afford to buy books -- and even then I would go to remaindered bins -- it changed all sorts of things. The internet, now, as you were saying, it really makes all kinds of things different. The last 15 year in the country and around the world -- but especially in this country -- there's been a re-appreciation of old illustration, advertising art, that isn't kitschy, that's really great work. And through my friendship with our mutual friend

Mark Chiarello, who's got a vast knowledge of all of this stuff, he really was an education in and of himself for me. "Have you seen this guy? Have you seen that guy?"

The Internet changed all of that because it's free.

HAMPTON: My education is essentially

my older brother, Bo. He's five years older than I am, and I'm glad to always offer that. He doesn't like me to say that. [laughter] He was really my greatest influence as a kid. I didn't go to school. He went to SVA for I think long enough to get a degree. He got his degree from there. He was mostly learning from

Will Eisner. He took Will Eisner's courses, and he apprenticed with Eisner. So I really kind of glommed onto what Bo was learning. So yeah, I've parasitized everybody I know for the longest time. I started with Bo. When I met

George Pratt and Mark Chiarello --

SALE: Were you in school with them?

HAMPTON: No. They were all at

Pratt. It's funny, we all met at the Thanksgiving convention in New York in the year 1981. This was the same year I met

Kent Williams,

Jay Muth, George Pratt,

Mike Mignola, Mark Chiarello,

Charles Vess I think was coming out that year, we all met at about exactly the same moment. It was sort of hilarious that so many of us went on to do stuff in comics. Jeff Jones was at that show as well. I would take the information they had. I could ask my simple questions. "How do you get this effect?" They'd tell me, and I'd say, "Great." They'd show me and then I could do it. That was my education.

I will still do that. I look at other people's work, I look at Tim's work, and I'll be influenced by that. It's all over the place. The comics education thing... I think that art,

per se, a lot of it you teach yourself. And honestly, if you were in a better place emotionally, even if that information wasn't that applicable to you, the inspiration you'd get from a Buscema and a Romita and a Marie Severin could have been enough.

SALE: Well, I was already inspired by them. It was different in person, and unfortunately not as inspiring in person. But their work captivated me the same way I bet it captivated everyone in this room. Buscema, especially: I was just so fascinated by what he would do. How easy it was for him, clearly. And when his brother inked him -- speaking of brothers...

HAMPTON: That's the greatest pairing, I think. It's amazing. Buscema inked by

Sal Buscema is still the best work. The

Silver Surfer work, I still think that's by far the greatest work.

SALE: His best work, yeah. They did a Captain America, too, did you know that?

HAMPTON: Really?

SALE: Yeah, just one.

HAMPTON: I'd love to see that.

SALE: It's... it's not much of a story. So it's nowhere near as powerful as the

Silver Surfer stuff. But yeah, they did one. Can't remember what it was.

SPURGEON: John Buscema might be a jumping off point to what may be an impossibly broad issue that I nonetheless hope you can speak to a little bit. Buscema had a wonderful way of drawing, where his single images were visually arresting. If you've ever seen his original art, he'd sometimes draw on the back --

SPURGEON: John Buscema might be a jumping off point to what may be an impossibly broad issue that I nonetheless hope you can speak to a little bit. Buscema had a wonderful way of drawing, where his single images were visually arresting. If you've ever seen his original art, he'd sometimes draw on the back --

HAMPTON: A

lot.

SPURGEON: -- these incredible single images. Unlike a lot of comics, and this would extend to painted comics of some varieties that have come since, Buscema's work really functioned as comics, they didn't work in a way that made the eye stop and rest. You could move through his stuff. He was very good with anatomy, and reasonably strong in terms of page design. I was wondering if both of you could speak to that tension in comics between those beautiful single images and the cartooning element that lies underneath a lot of it. To tell a story, to make it move. How long does that take to master. I could imagine that even being a lifelong task. You're both solid single-image makers, but both of you have done work that really reads well as comics.

HAMPTON: Of the two titles, I'd rather have "cartoonist," personally. The greatest single enjoyment I get from working in comics is the storytelling. Whenever I can I write my own material. I love telling stories, and trying to get better at that. I do think, though, that... it's funny, in the early 1980s when painted comics started to happen, and I was one of the first ones doing that, along with

Bill Sienkiewicz, Kent Williams, and some others, we were basically just jumping into the storytelling world without having enough background in it to do it effectively. But hey, it was new. A new experiment.

I still think that over time painted comics and digital comics and all the tonal ranges that can be created can have their place in comics. I've backed off of the feeling that a painted comic is necessarily... I can't get over those floating balloons. They're so flat, and they're so outside the painted work.

SALE: Yeah.

HAMPTON: It separates, and I don't like that. I've never liked that. I get upset. [laughs] I said to

Archie Goodwin, "Look I want to paint my ballons. I want to do them in color, and I want do them with texture. I want to have them integrated in some fashion." And he goes, "Yeah, and if the separations are at all off, then the reader can't read the words." And I was like, "Look, use the lettering as a way to keep the separations from getting messed up." [laughs] You know? The sepia lettering, if it's the least bit fuzzy, they know they have to fix it. He was like, "You're expecting too much from the printer." So it never really happened. I don't want to get too bogged down in that, but what I'm saying is that the painted work runs a risk of being very static and seeming like still images and postcards rather than a story. The most wonderful thing about comics to me is that when you start to read it, the visuals become like butter, and you're just grooving along, and you're not even aware of the pictures. You get it, but they're not stopping you. They just keep you flowing along. And if they do stop you, hopefully it's for a reason.

I have a formula for that. I think for every hour I spend on a panel, I'm getting the reader to look for one more second. If I spend six hours, almost a full day, doing some sort of establishing shot. Essentially I'm kind of wanting the reader to take it in for six seconds, which is a lot more than they would normally do. But I never want to interrupt the flow, and I never want to get in the way of the wonderful things that can happen in a comic book. Honestly? We've got a long way to go in terms of tonal work and painted work to make that maximally effective. I sometimes think that a painted comic is... if I want to paint the perfect comic book, it'll be a woman, sitting by a window, drinking a cup of tea, and thinking out loud, and maybe the phone rings and she talks on it. The End.

It can't be too active. Because as soon as it starts to become very active, the painted work tends to irritate me if it's too realistic. The more of an integration of line and painted work -- someone like

Lorenzo Mattotti, or

Teddy Kristiansen -- that's inspirational, because whatever they're trying to get at I believe it because there are those graphic elements of line. It says I am not divorced from the story. I am kinetic. I incorporate a great deal of line work into my painted work in order to deal with this problem. From my perspective, the painted angle, that's the struggle.

SALE: Teddy's work is more graphic. Teddy's work is definitely graphic. It's paint and line. It's both, as opposed to lustre. That is a kind of hybrid. What's this woman look like in the room drinking? I'm trying to conjure an image.

HAMPTON: She's an old woman. Yeah.

SALE: That's different than my image. [laughter]

HAMPTON: Did you woman have clothes?

SALE: She had clothes. Plenty of clothes. A big, fluid skirt.

HAMPTON: That's the thing. When it comes to a flowing skirt, when it comes to material with textures -- satin, rock, wood grain, -- atmospheres, fog, all the rest of it, you kind of can't beat paint for creating those things. The more that you approach the way we see the world, optically, which is to say tonal rather than line, the closer you get to that, the more the reader I think says to himself, "All right, I'm being presented with something. I'm not engaged in it,

per se. I'm not being asked to be involved with it. I'm basically being shown something." And to show them is exactly what comics

isn't supposed to do. You're supposed to engage them, get them to lose themselves in it. For that, let me point to

Bill Watterson and Calvin and Hobbes. He's done painted comics. They're in the front of the collections. They incorporate line, but they're also watercolor. To my mind, his are the most effective painted comics there are. You buy the reality that he establishes, however wonky the drawing. It's beautifully drawn, but it's not realistic. He makes you believe it. He sucks you into that whole world of his, and the painted work does not in any way impede your ability to buy into that which is happening in the moment.

SALE: Scott, do you know

Blacksad?

HAMPTON: Black Satin?

SALE: Blacksad.

HAMPTON: Black Sand.

SALE: S-a-d.

HAMPTON: The panther. Yes, I've seen that stuff.

SALE: That's painted, but it's definitely comics. I highly recommend it, not just to highly initiated crew over here but to everybody. It's going to be reproduced by Dark Horse sometime later this year. There are three volumes in print now. He's working on the fourth -- it's two Spanish guys.

Juanjo Guarnido and

Juan Diaz Canales. They both worked for Disney France as animators so there's an incredible liveliness to it, movement and power. It's anthropomorphic. I thought it was a panther, too, but I spoke to the artist and he said, "No, it's a house cat." Big thick neck. [Hampton laughs] Black.

It's a

Bogart movie, but with animals, on two feet and wearing clothes, things like that. And having sex. It's amazing. They're shooting each. But that's a great combination, because I completely agree with your point that when you have illustration without line, especially when it's

Alex Ross or somebody where you're supposed to be impressed. I get that feeling from Ross's work so much of "Look what I can do." The photo reference of it all. That's exactly the opposite of what you want it to be. In my opinion.

HAMPTON: I secretly agree, but it's bad form for me to say that. [laughter]

SALE: I can say it. I don't have a career. Back to talking about storytelling. A lot of it is instinctive for me. And I've oftened wondered why I could not begin to get it when I was at school, and how that somehow over the years became instinctive. I studied it, I do follow certain things. There's a gentleman in the audience here... I have a message board on my web site and one of the topics is a page a day of mine. He's a pain the ass but he's very thoughtful, and he looks very hard at things. He wonders about storytelling. He often points out things were I'm like, "I guess that's there, but didn't really plan that out."

I always thought of the old axiom that you should be able to follow a story without words: that the words added a tremendous amount, but on a basic level you could go panel to panel and have a sense of what the story was, what was happening. And what led to the next. So visually leading from one panel to the next, and you're reading left to right, the action goes left to right. That kind of thing. Establishing shots. You make sure that the most important thing is easy to find. Then you can add stuff. I'm working on a

Captain America series now with

Jeph Loeb and it's full of double-page bar scenes, where there's five different conversations going on. It's fun trying to coordinate all of that, and a challenge. How you make the eye move, and what you stick to. You have to pick out the most important thing, and then the rest of it is there if you want to slow down and look at it. But you're not holding up the story.

HAMPTON:

HAMPTON: It's this strange hybrid. That's why I asked you about reading the

Conans, Tim. You were a reader then. My thing is I was into the visuals and I didn't read them for a long, long time. As an adult I started reading comics but I was only looking at them for decades. So I didn't appreciate

Johnny Craig. He's one of my favorite people now. You may not have heard of him, but he's an old-timer from the '50s and '60s. I love his stuff. But I didn't then.

That's the thing. That's the thing. It's something about the visuals. The more the visuals are impressive and interesting and make me just want to look at them, the less I'm wanting to read the story in some sense.

SALE: Especially if your history was looking at the pictures and not reading the stories, right?

HAMPTON: The people that all got to me in the '60s... my first love in comics was probably

Jim Steranko. [laughs] He was an incredible experimenter in terms of style and graphics. It was eyepopping and just blew my mind. But none of them imputed to me the least instinct to read. I became a reader later. I value the reading of comics and the story of comics now more than I do the visuals. The thing about the

Chris Bachalos of the world... look, we're making a deal with the devil. We have comic books in the world because you're asking people that are mostly visual to become storytellers. And it's not instinctive. It's not intuitive, necessarily. And sometimes they do just get caught up in the design and the look of it. Honestly, I give them some room to do that because I know what it's like to feel like I'd rather focus on the visuals than the story. But I very much admire and want to become a much better person at making a story flow, the rhythm of it and the pacing.

There's nothing that will make you want to do that more than writing your own story and wanting to maximize it visually. It's different when you've got someone else's story, you can kind of be a little bit glib about it. "Well, that's that. I'm going to draw this cool stuff." Not so when you've written it yourself. Now you want it to communicate.

SPURGEON: Scott, you mentioned Lorenzo Mattotti earlier. Two of his painted works,

SPURGEON: Scott, you mentioned Lorenzo Mattotti earlier. Two of his painted works, Fires

and Murmur

are almost tone poems more than straight narrative. I wonder if you could both talk about tone and mood, either subliminal or overt in comics. The kind of comics where you may read it and have a reaction that's different than the surface reaction. Mike Mignola yesterday talked about reading Jim Woodring's comics where he would all of the sudden feel scared without knowing exactly why. Eisner and [Alex] Toth were both great with tone and mood. Certainly as accomplished as your work is... I wonder if you could talk about tone in terms of narrative.

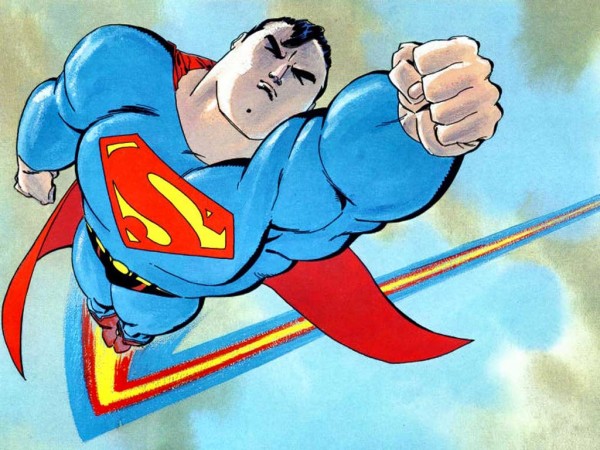

SALE: If I had to single out one thing, tone and mood is my main thing. I am known for using a lot of black, but I also did a Superman story where I wanted to do the opposite. I wanted the tone, the mood to be different. It's almost a coloring book. I put a lot of texture into the line, but there was almost no black. I wanted the color to be a big part of it. That was very scary. That was before I had a computer, so I didn't see any of the color. I drew this coloring book, and I had no idea what it would look like until it was printed. The good old days. [Hampton laughs] But I did it that way on purpose. The mood and everything was the reason. I keep myself amused by trying different techniques, trying to fit a different technique to the story I"m going to be telling. Superman being different than Batman I wanted to really open it up that way. My friendship with Mark was really blossoming, so we talked about

Rockwell in particular. His depiction of Americana I though was really

apropos of how I thought about Superman. The Kansas stuff -- really different than Gotham City and the angst.

I'd like to do a romance comics. How would I draw that? Draw it like a Toth.

Try to draw it like Toth.

HAMPTON: The different stories, I look at them and ask how I'm going to approach them. I struggle with that.

Stanley Kubrick said something wonderful, that the more you know the harder it gets. What he's saying is that when you have a limited number of things you can pull of your choices are few and you don't have to worry about them. But when you can draw fifty different feet, you have to choose. It's problematic at times. As I've gotten better and I've learned more and taken in more techniques, I sometimes find it difficult to decide how to approach a specific passage or story or whatever.

When it comes to tone, effects of mood and tone are things that draw me in. I love to try and create that, whether with black and white or with color. It's funny, and I don't know if it's really on topic but I want to mention it. You can tell a young artist from an older artist because the young artist will have an office scene of two guys in a office talking and it will last three pages. It will start with a simple side shot, and then the next thing you know it' a bird's eye view of the guy, and then a worm's eye view, and then he'll show it from outside and then he'll do a big eyeball. He's trying to juice this boring scene visually.

SALE: That sounds

great. [laughter] I want to read that!

HAMPTON: Exactly. The problem with that is that is' in defiance of the story. The thing about tone is that everything has it. You have to figure out what kind and then try to make it as both appropriate to the moment and then interesting as you can without shattering the thing and making it just visually fun without it being that kind of story.

SALE: It also helps if the writing is compelling.

HAMPTON: Exactly.

SALE: Not just compelling, but the writer also understands comics, so you build into a moment -- set-up, set-up, set-up, punchline; maybe not a joke, but a finish to it. That has to lead to something else unless it's the end of a scene. If it's two people arguing, two people deciding what to have for dinner, two people fighting crime deciding you have to go here and you have to go there, all that leads you as the person doing the pictures to how you're going to draw it. What's the room loook like, what are they wearing, what is the lighting. That's plenty. You don't have to do the eyeball.

HAMPTON: You say they're in a room, but I don't see any reason why they can't be walking around. If I can I will get them to walk around, and will take them into a park, and I will have some other things to see. This is a technique that they used in a television show

The West Wing.

SALE: Walk and talk.

HAMPTON: West Wing is a very static show, but they're constantly motoring through those hallways, aren't they? That's visually more interesting, and it gives you something to focus on, and you get the life of the place. You see what I'm saying.

SALE: The camera is moving, too. That in and of itself is...

HAMPTON: If there isn't a compelling reason to say in a bathroom, I'm leaving. [laughter] I will find a way to get to the roof. I want to see some ducks, and I want to see some birds. Then we'll go back to the bathroom. [laughter]

SALE: When you first said moving, I thought you meant moving in the room. You don't have to leave and go do stuff. If for instance they're talking and it leads to a moment, the punchline idea I was talking about, if one guy is walking around angsting about something, and the other guy is sitting there with his arm closed and he's talking. And the guy angsting is not speaking but listening intently, and the punchline is that he stops and turns and looks back. Over the shoulder, or you hit the lighting a certain way. That's a punchline. There's been action, movement that adds to what the words are, and draws attention to the scene without drawing attention to itself. Plus it's what people do. All that is storytelling as well.

HAMPTON: I agree.

SALE: I have a lot of fun with that.

AUDIENCE QUESTION: I actually did not know, Tim, that you were color blind. What I like about your stuff is how you use color. [laughter] I was wondering now that you've said that, that this has made you better with the black and white visually because of the color-blindness.

AUDIENCE QUESTION: I actually did not know, Tim, that you were color blind. What I like about your stuff is how you use color. [laughter] I was wondering now that you've said that, that this has made you better with the black and white visually because of the color-blindness.

SALE: Yeah, I'm sure it has. I've always been drawn to contrasts. Before Mignola or

Sin City or things like that, Toth was -- does everybody know Alex Toth? Longtime artist, did many different thigns in comoics. Many different styles of thigns. A real artists' artist. He increasingly said "Make it simple, make it siple, make it seimple -- wihtout making it simple. It was very complicated. His work in

Eerie was mindblowing to me; they were black and white, sometimes it was wash, sometimes heavy black and white. Johnny Craig did some work for them. Frazetta did some work.

Angelo Torres. There was a group of people that they --

Reed Crandall -- sort of a stable of artists, and Toth was an infrequent contributor. I think

[Steve] Ditko's best work --

SPURGEON: His wash work in that period is amazing-looking.

SALE: The Fly, things like that.

HAMPTON: "

Collector's Edition." "

Deep Ruby."

SALE: I highly recommend all of that stuff.

Dark Horse is doing a good job of putting all that out again. All that was really high contrast. The more high contrast it was, the more I was drawn to it. I didn't know at the time that I was color blind. But I'm sure that was a big part of it.

HAMPTON: What is your color blindness? Is it red-green?

SALE: It is not red-green. I was being interviewed in Barcelona at a con, and it turned out the guy was an optometrist. He knew exactly what I had, and that there were twenty different kinds. I didn't get him to write it down. The easiest way to put is I can't create with color. I can see blue, I can see red, I can see yellow and stuff. I can tell your shirt is a different color blue than the chair, but I wouldn't know how to make one or the other or what should go next to it, or that if you add a little magenta to this... that's what I can't do. With the advent of being sent jpegs, I've been blessed to work with people like

Greg Wright and

Dave Stewart, Chiarello, who are just fantastic colorists, and in the case of Mark and Dave amazing in their use of the computer. Bold and entirely appropriate to comics. I'm not a big fan of the lens-flarey stuff, or the smoothness. It's not like I see the world in black and white. I can look at Dave coloring

Darwyn Cooke in

New Frontier and say I've never seen anything like this before. I'd literally never seen anything like that before. How he got the computer to mimic other graphic things. Darwyn's great at that.

HAMPTON: I'm not color blind. [laughter]

[Mike] Kaluta has a color blindness.

SALE: Toth. Toth, actually.

HAMPTON: Yeah, Toth.

SALE: John Byrne.

HAMPTON: One of my very favorite artists was

Robert Fawcett and he, too, was color blind.

SALE: Was he really?

HAMPTON: He was. His wife made the color choices for him. He knew there were hues and gray and stuff, but that's all he could see. So she'd say, "I think you oughta go with pink for the dress this time." And he'd go, "Which one's pink?" "That one." All right.

SALE: I did not know that. [laughter]

*****

*

Scott Hampton

*

Tim Sale

*****

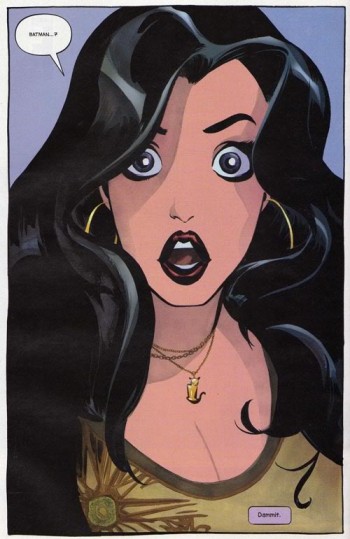

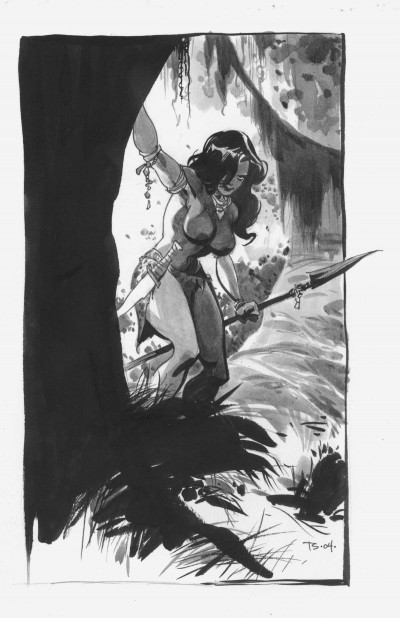

* art from the respective artists: Hampton, Sale, Hampton, Sale, Hampton, Hampton, Sale, Sale, Sale (last one below)

*****

*****

*****

posted 12:35 am PST |

Permalink

Daily Blog Archives

November 2019

October 2019

September 2019

August 2019

July 2019

Full Archives