October 4, 2009

On The Subject Of Return Reading

On The Subject Of Return Reading

The author and music writer David Gates penned an article this summer for

Newsweek on

the pleasures of re-reading. Gates seems to view re-reading as way to spend time in the company of memorable characters that have touched him in his lifelong give-and-take with literature. It further seems he experiences this pleasure through specifically lively usage of language. Gates appears to be enamored of Charles Dickens, in whose works the characters' names are frequently worth a second visit all by themselves. I found Gates' piece fascinating for the accrued force of his recollections and for the amount of conflict it sparks in him about what those books he reads indicates about his own life, its predilections and potential shortcomings.

I think comics has a harder time than prose with the question of what gets read over and over and why. The various comics industries' longtime devotion to impermanence may have fostered a suspicion of reading a few works a bunch of times as opposed to as many works as possible a single time or two. A comics reader remains in many ways measured by the breadth of her pull list rather than the devotion she might feel to a few great works, and nasty, dismissive words are common when discussing those whose interest in comics is limited to a specific genre, artist or kind of story. Further, comics are such a powerful expression of nostalgia and act as such highly effective totems of negotiating childhood issues and rough life periods that there's a tendency to want to equate re-reading with the kind of emotional wallow many of us have experienced diving back into a big stack of mental comfort food. I know that I can help find my way through a down period armed with a large stack of comics that feel and smell a certain way. At those times, the specific comic doesn't matter as much as it being

comics.

As I get older, however, I find I return to very specific comics to re-experience their inherent virtues, that I'm spending less time reading comics in general than I am trying to fully and effectively read and re-read the great comics or the comics that are important to me. Here are four that I find on my night table more than once a year, and some reasons why this may be so.

*****

Hicksville, Dylan Horrocks, serialized in Pickle 1992-1996, published in book form 1998, Tragedy Strikes Press/Black Eye Press/Drawn and Quarterly.

Hicksville, Dylan Horrocks, serialized in Pickle 1992-1996, published in book form 1998, Tragedy Strikes Press/Black Eye Press/Drawn and Quarterly.

It's not difficult to figure out why I might have been interested in

Hicksville during its serialization in Dylan Horrocks' great comic book

Pickle. One of its main characters and arguably the audience's viewpoint character is the comics critic Leonard Batts. In the mid-1990s I was one of maybe a half dozen people in the world who could argue that he had Batts' job or something very close to it (there are many more now). My job did not involve writing books about Jack Kirby or being sent around the world to track down the biographical details of a prominent cartoonist. It did mean I paid a lot of attention to comics and cartoonists without being one of their number, a feeling of being part of a special club but far outside of it that Horrocks nailed.

Hicksville went on to become a beloved graphic novel for many people enamored of cartooning, particularly those in the post-alternative generation who I think were looking for a narrative that spoke to their struggles with the art form that didn't express it as a push away from mainstream comics, a rebellion against content and practices about which they might not have felt strongly in the first place. I think its success is due in part to the fact that Horrocks manages to suggest something deeply mysterious and wonderful about the making of comics and a care in reading them that ropes in the horrible futility experienced by many of its best creators, then and now. Some people complain about its lighthouse metaphor being way too spot on, but I think there's a solicitousness that should be appreciated when it comes to Dylan's choices of metaphor and meaning. There's something to comics that the creation of a bold metaphor can have meaning to people who read the story even as the actual thing has meaning to the people in the world where they get to walk inside the thing. It's tough to love comics sometimes. Let them have a lighthouse.

Going back to

Hicksville always feels to me like getting to have a long conversation with Dylan about art and related issues. It's interesting how much that conversation changes even though the book has remained the same. More of

Hicksville is revealed to me each time out. In terms of its narrative, I'm usually struck by how measured Dylan's pacing and tone are, how little happens and how much heaven and earth move -- sort of literally -- on the relatively modest decisions about life and art embraced by the characters. In fact, the more I read it, the more I tend to see the characters over the ideas they represent. I don't wonder after comics as cartography as much as I might have 10 years ago, but I ponder Grace's garden quite a bit, the wisdom of returning home and the way that none of our personal lighthouses have much to do with comics and that's okay, too.

As The Kid Goes For Broke, Garry Trudeau, Holt Rinehart and Winston, 1977.

As The Kid Goes For Broke, Garry Trudeau, Holt Rinehart and Winston, 1977.

I have no desire to read

Doonesbury on a daily basis. Unless I'm reading a newspaper that carries it -- my local doesn't -- I never even see Garry Trudeau's still slowly unfurling document of Baby Boomer adulthood. When I do, I'm surprised by how relatively handsome it is, and how sympathetic his strips about the soldiers are, and how he's solved a lot of the problems that used to crop up when he dealt in abstractions of real-world figures rather than allowed his amazingly diverse cartoon cast to carry those moments. I recognize its quality, and suspect that making it still gives its cartoonist a charge and thrill. I'm happy to remind people that it's arguably

the great comics feature still running.

The

Doonesbury comics I frequently read are the 1970s book collections, the small white books from Holt that carried four panels per page in a box format and resembled in their proportions and modesty similar collections from any number of popular gag cartoonists of the time period. There's nostalgia involved, sure. Because

Doonesbury was comics, I read it far ahead of my interest in its subject matter. It seemed to me a very adult strip, in that it reflected the way I heard adults talk to one another when I was in the room being quiet or otherwise unobtrusive. As adulthood was a club that would barring a movie of the week outcome eventually have me as a member, and as a member of 1970s American culture I was certain at all times that I was not being given the best information possible, I paid an inordinate amount of attention to Doonesbury just trying to decipher what the hell all these people were up to.

The great congressional campaign storyline in

As The Kid Goes For Broke -- one of Trudeau's career highlights and one of the best comics of the 1970s in any format -- was the first time in any medium I'd seen people pursuing jobs that seemed personally fulfilling and fun. This was a great boon in imagining some sort of future for myself beyond becoming an important pawn in a world-shattering end of millennium contest between good and evil. There was a casual certainty to what was going on that seemed like it was loaded with insights, anyway. It held a truth that was not literal truth.

When I read the book these days I'm struck by how fantastic a character Joanie Caucus is, and how little she gets mention in examinations of the great comics characters. There's something that feels much more real and observed about Joanie Caucus than even those characters in

Doonesbury with easy-to-nail, real-life antecedents. It's so, so difficult to make an

admirable character that's still as funny as Trudeau makes her. I'm also reminded how hard

Doonesbury hit with audiences at the time. For one thing, I'm pretty certain that a criticism aimed at Trudeau in those days -- some years before Scott Adams came along -- was that he was a terrible artist and the strip would improved 10,000 percent if only he could find a decent craftsman to see his vision through. This seems absurd now, but it's fun to look at some of the oddball aspects of Trudeau's character design -- the big, wide, eyes that looked so ugly in people aping his style, for instance -- and some of the solutions (static imagery, voices off panel, dropping details) that he may have employed to avoid having to draw certain things in explicit fashion. I don't know if Trudeau's comfort drawing was part of the origin of the silent third panel he mastered and every single cartoonist has at least thought about using since, but that's a delightful craft element to track, as effective a use of silence as any Jack Benny employed.

The best-known sequence in the book is all silent panels, of course: Joanie and Rick Redfern in bed together introduced to us by a sweeping view through the neighborhood. It remains hilarious not for the skill displayed in that silent lead-in, but for the confidence Trudeau had in doing that part of the story that way in the first place. As the kid goes for broke... For most people this would something you'd consider only if you were to never do anything with the characters again, and you probably wouldn't go there anyway. (For a reverse gender example from that same period, consider the Mary Richards/Lou Grant kiss and giggle.) Trudeau never hesitated and never blinked. If that means there's an element of rooting for the characters that seeps in, let me ask you this. Was there ever a better character to root for?

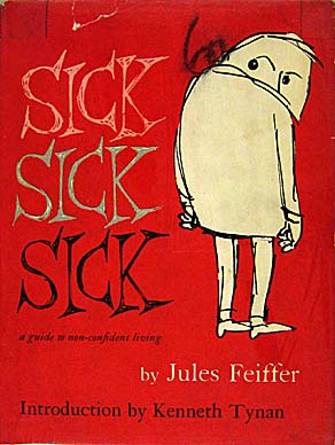

Sick Sick Sick, Jules Feiffer, serialized in the Village Voice starting in 1956 (the strip would later be renamed Feiffer) and first published in book form in 1958.

Sick Sick Sick, Jules Feiffer, serialized in the Village Voice starting in 1956 (the strip would later be renamed Feiffer) and first published in book form in 1958.

I think Jules Feiffer's

Sick Sick Sick is a perfect comic book. The one I re-read is a fourth or fifth edition, basically the one depicted above and the general volume most people I know think of when they think of this work in print form.

Sick Sick Sick has many excellent surface qualities; if you were a character on a sitcom, you'd pay it to go with you to a wedding. The book's great-looking, it's of a size that is pleasing to hold and read, it's of a length that flatters Feiffer's unique voice, the material inside remains poignant and its overall historical significance is undeniable. It is all by itself proof that comics for an adult, sophisticated readership can exist, that they can be done in a style far away from given commercial standards, and that they can yield major artistic returns. It did this decades before an years-long movement came to the same conclusions. It is singular and it is Ruthian.

It's also fun. Feiffer's cartooning is so lively here. Feiffer's running men and the way he draws slumped shoulders and his tiny women are all pantheon-worthy in terms of the art form's great visual depictions. The bitter disappointments of manhood in the post-War world and neuroses that drove so many novels were also rich territory for Feiffer, maybe richer because of the deep subtext afforded in giving these expressions a visual life and the modest act of Greenwich Village-style, insouciant rebellion that was taking on such subjects in cartoon form in the first place. This was another book I used to try and understand adults when I was a kid, although it'd be years and hundreds of readings later before I realized that many of the concerns upon which Feiffer seized were funny because they were beyond easy understanding.

Feiffer's had a wonderful career, in cartooning and as a writer, which is almost a minor miracle in itself given how trailblazers tend to be treated vis-a-vis the group that follows and dumbs things down. Reading this very great book as I like to do every month or so I'm still astonished by how little credit he's given for the towering accomplishment of creating work that was two or three decades away from fostering a sustained movement. If we valued the graphic novel as much for its capacity for psychological insight and ability to deal with sophisticated issues and propensity towards expressive artwork as much we do for the number of pages involved, Feiffer would rightfully be seen as one of the major cogs in its creation. As things stand, his work exists in its own little world, and this startling, ground-breaking phase to his career continues to call me for round after round of personal reckoning.

The Death Of Speedy Ortiz, Jaime Hernandez, serialized in Love and Rockets Vol. 1, reprinted in multiple collections since.

The Death Of Speedy Ortiz, Jaime Hernandez, serialized in Love and Rockets Vol. 1, reprinted in multiple collections since.

I had a significant crush on

The Death Of Speedy Ortiz the summer I was 20 years old, reading and re-reading the serialized story with a passion I had never brought to a single comic story before then. There are a number of Hernandez Brother works from that general time period that feel special to me for their content and for how completely each knocked me on my ass: "Tear It Up, Terry Downe," "For The Love Of Carmen" and "Frida" all spring to mind. But it's "Speedy Ortiz" to which I always return. It's such an irresistibly sentimental and sweetly romantic story on so many levels. It's full of nighttime adventures of the kinds that only young people can have, the promise of sex and violence, lovers kept from each other by fate, friends and family sticking up for friends and family. The story's ending is a Godzilla-sized choke-up moment of Speedy's goodbye and the final reveal as to his fate, followed by the next page's King Kong-level gut-punch of a moment from the characters' past where they're all heading different directions towards the same depressing result. I think people sometimes take it less seriously for its appealing qualities, as if there's something too easy or smoothed-over about this approach. I thought it was wonderful that summer I read it 10,000 times, and I remain convinced it's a special story every time I've picked it up since.

Although I'm a long way divorced from the mind-set shared by so many of the characters in

Death Of Speedy Ortiz, and most importantly have broken with the simple desire it invoked in me to want to live way Hernandez depicts these people living their lives, I like the comic more than ever for its power and luminous art work and what I see now as instances of narrative restraint. There are stunning panels in here -- Maggie and Speedy sharing a kiss at a barbecue, a moment of Maggie as she likely appears to Ray, Litos flailing his arms around as a sign of the youthful energy he can't leave behind -- that illustrate instances that aren't high moments of action but the way we assemble memories and ascribe meaning. A gifted and unappreciated writer, Hernandez further underlines the story's theme by shifting much of the action off-line and focusing on the reaction that the cast members have to those moments. Even a crucial instance he depicts within the story, a drive-by shooting, seems more important for the way in which both of the major characters involve react than for the physical consequences involved. When I read

Death Of Speedy now, I see a little bit more of how Jaime Hernandez uses single moments and narrative flow to comment on how we forge a past.

posted 8:00 am PST |

Permalink

Daily Blog Archives

November 2019

October 2019

September 2019

August 2019

July 2019

Full Archives