Home > CR Interviews

Home > CR Interviews A Short Interview With T Edward Bak

posted November 10, 2007

A Short Interview With T Edward Bak

posted November 10, 2007

*****

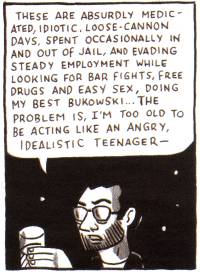

A lot of comics cross my desk. While I'm pleased by a great many of them, I'm surprised by very few. The biggest surprise in recent memory came just a couple of weeks ago in the form of T Edward Bak's Fall release from Bodega,

Service Industry. I missed out on both the serial version and the mini-comics version of this work, and I think my sole exposure to Bak's comics was his crude but energetic contribution to the Victorian horror anthology

Orchid. I was therefore unprepared for the visually engaging cartooning, smart writing and formal playfulness of the new, over-sized publication. I read it three times in a row. A mix of autobiography touching on the cartoonist's time working in restaurants, fantasy and polemic, Bak leaps back and forth between settings and storytelling modes with ease and grace. It's a solidly crafted and narratively compelling comic book, done in an idiosyncratic style that distinguishes it from other works of its type. I dream of a world of constant discoveries like this one. By the end of the book, I was thrilled to add to my list yet another cartoonist I plan on following for a good, long time.

I spoke to Bak at his home in Vermont, where he was getting ready to watch

Five Easy Pieces.

*****

TOM SPURGEON: Am I right in thinking you're some sort of artist-in-residence at CCS?

TOM SPURGEON: Am I right in thinking you're some sort of artist-in-residence at CCS?

T EDWARD BAK: Basically, I'm the fellow for the

Center for Cartoon Studies right now. It's kind of an artist-in-residency position. I was awarded the fellowship and came up for the 2007-2008 school year. They have a two-year program here.

I don't want to say it landed in my lap. I went after it. I was living in

Portland at the time. I had been living in

Georgia and moved back to Portland a couple of years back. I was out having breakfast with

Zack Soto and

James Sturm called me right before we sat down. That was March or April this year. I started talking with people here at the school, and they were telling me, "Come on up! The sooner the better, you can get settled and acclimated." I'm like, "That sounds great." So I get up here in June and there's nobody fucking here.

SPURGEON: [laughs]

BAK: They're all gone. I just got here and sat around and started to try to get acclimated -- but I still don't feel acclimated.

Rural Vermont, it's like 2500 people in

this community. Athens is like 50,000 people. This is so much smaller. It's New England, so there are all these little towns five to ten miles apart. It's not totally isolated. But there are no big cities around here at all.

SPURGEON: Did the fellowship come from the school itself?

BAK: Yeah, it's from the school.

SPURGEON: So what do you do as a fellow? Do you teach? Are you there as a resource?

BAK: I work on my own projects and I'm a resource if they want to use me. I don't think I've been very useful. [laughter] I think they're like, "He doesn't have anything to say; we're not going to consult him for anything." I'm accessible to the students if they need me. I've made one presentation so far, and I'm expected to make more. I might have a presentation next month;

Steve Bissette asked me to do something.

I'm working on a project with the students that's a rotating door comic strip, so each one will do a strip about something historical in the area.

Upper Vally Ephemera. I'll be the editor and pitch it around to newspapers. This is my idea; I want to get them involved, get them published, see how deadlines can be worked out and give them an idea of what it's like to do a weekly strip. I'm sure we can get a newspaper in the area to pick it up. I'm into doing small projects like that with the students.

SPURGEON: I know that dealing with students can be interesting for artists because you're facing younger people and playing a different role than you might be used to playing. That can be unsettling for some people.

BAK: I've never been in a position like this, I can tell you that. I've found it to be quite a challenge, because I don't feel like... I was actually just talking about this earlier. I felt pretty enthusiastic about being involved with the school in this aspect because I thought these students have to be really amped about new comics, new work, new artists, and thought this would be a good opportunity to see what they think, see what they're going to do, see what they're interested in doing. Some of them are interested in new stuff, but there's a really solid focus on history and on homework that's comics based, they're very involved in school work that I've kind of had to get into the position where I hang back. I need to be focused on my work and the project I'm working on with the students. They have enough to deal with it as it is; they don't need me as the fellow or whatever bothering them. I don't want to challenge the instructors and contradict anyone. Just trying to have my own space and my own work at this point.

SPURGEON: The first time I remember ever seeing your work was

SPURGEON: The first time I remember ever seeing your work was Orchid

. Were you a latecomer, or was I just not aware of you for a very long time?

BAK: I'm a latecomer. I had done a couple of small, self-published runs of things. I had done a comics/card project

[Firefly Waltz] that I was really excited about at the time which was handmade and was really different. A few people got that. That was the second time I lived in Portland and I was beginning to make friends with some cartoonists on the west coast. Around this time,

Dylan Williams and

Ben Catmull asked me to participate in the

Orchid project. I was really excited because it was the first real anthology I was going to have anything to do with. So I jumped at that. I hadn't really done anything like that before. That was 2002, I think.

The earliest thing I had done before that on my own was

FLUKE which I started in Georgia. I think the first one was 2002, and I think

Firefly Waltz was 2002 and

Orchid came out a little bit later. That's basically how I kind of got started doing my comics. I had always had an interest in it, but I don't think I was ready until '99 or 2000 to really get serious about it. I had been working on a lot of different ideas up until that point.

SPURGEON: How do you look back on the FLUKE experience? One thing that someone wrote about FLUKE is that it was more about celebrating that scene than about a showcase, that it was great just to find out who was in town and who was working on what. That's not exactly a big commercial aspiration. Seeing that was five years ago now, how do you look back on that time?

BAK: In Georgia I was isolated from the cartoonists who I felt more of a kinship with on the west coast and in

Montreal and

New York. I really wanted to do something different. I thought, this is Athens, Georgia, which has a reputation for its music scene. There's a lot of arts, too, and I thought it would be interesting to have everything together in one place, music and comics, have it all in one space, and encourage everyone who was doing comics in the area to come. I didn't even know about

SCAD at the time, I had no idea what I was doing. I had no idea to delegate authority. I had no idea what was going on.

On a whim I got a hold of

Jeff Mason and Chris

Staros. They were like, "Sure, we'll help you out." So they ended up being a couple of early sponsors with

Top Shelf and

Alternative. We had local businesses who chipped in here and there. We set it up in a bar. We did the comics thing with local people. One or two people came from way out of state. One guy came from Texas. The guy who does

Optical Sloth, Kevin [Bramer], he came down.

Sam Henderson and

Rich Tommaso came a couple of the years I was involved.

I had no idea what I was doing. I was homeless at the time. My girlfriend had just kicked me out. [laughter] I'd lost my job. I had nothing. I was losing my mind, and this was the only thing I had. It gave me some focus. One of the artists who worked for the local newspaper really liked my card thing and she offered to put it on the front cover of the newspaper. For me that was like, holy shit. It was some kind of validation. People responded to it. Later that year I began working on the

Service Industry comic strip.

SPURGEON: That kind of community building -- has that been good for you to have these relationships?

SPURGEON: That kind of community building -- has that been good for you to have these relationships?

BAK: Yeah. I think I was skeptical of SCAD artists in the beginning, and I didn't know how that was going to turn out.

Drew [Weing] and Eleanor [Davis] moved to Athens and started working with Robert Newsome and

Patrick Dean. I don't know if you've seen

the new FLUKE anthology, but it's fucking unbelievably beautiful. It's one of the nicest anthologies I've ever seen. That's five years after we did this hand-stapled Xeroxed thing. I haven't had anything to do with it over the past few years, but seeing that is like, "Wow." Seeing it at

SPX just blew me my mind. It looks so beautiful. They did such a great job. Drew and Eleanor are phenomenal cartoonists, too.

SPURGEON: They're horrible people, though. Jerks.

BAK: [laughs] Yeah, especially Eleanor. No, they are both genuine sweethearts.

SPURGEON: Can you tell me how

SPURGEON: Can you tell me how Service Industry

started in terms of the concept involved?

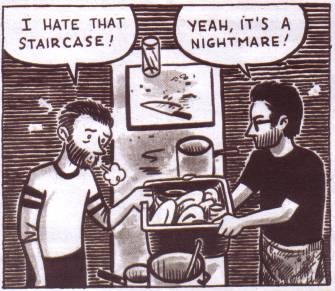

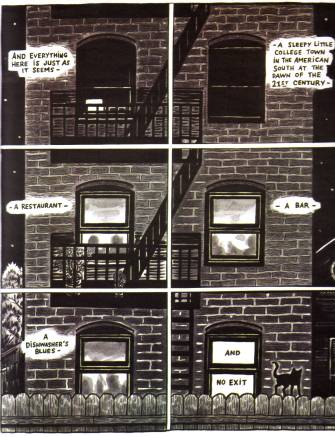

BAK: Originally, the idea came from how I had been working in food service and hospitality since high school, off and on, odd jobs. After FLUKE I finally did land a decent job working in a public library. I was also working nights in a restaurant in downtown Athens. I'd had this idea for many years, that it would be great to have something set in a restaurant, a day to day kind of thing. I wanted to do a strip about this and started working on this idea with this ensemble cast, all these great characters. All these interactions. But none of that actually worked out in the strip. I kept writing this autobiographical stuff over and over. I never had the chance to put these characters in there.

It ended up being a monologue with the occasional character popping in and saying something. Then for a while it had an anti-war angle because for the first time since high school I was fired up about what was going on. It was so mind-boggling. I started reacting to that stuff in the comic strip. I wanted to do something more autobiographical, more about me and my life. I started working on this story and wanted to examine some personal stuff. I had nothing to lose, so I could throw everything at it. It was very stressful. When it was finished I thought I was going to have a nervous breakdown, actually. But it turned out OK. It enabled me to clear some family cobwebs out, too.

SPURGEON: So the book that Bodega's done is that story, the more focused autobiographical run.

BAK: Yes.

SPURGEON: Now, it was Flagpole

that was running this originally.

BAK: Flagpole Magazine, yes.

SPURGEON: It's an over-sized book; how big were the pages that ran in Flagpole

?

BAK: Each page was one week of the strip.

SPURGEON: Good lord.

BAK: Yeah. [laughs] If you jumped in like week four or five you were never going to get it. And some people didn't!

Charles Burns had warned me, "Don't try to give them anything more than four or five weeks. You'll lose them." I'd seen it with

Big Baby; that was tough to follow. I was like, "I don't care! I'm going to throw everything into this." So I did.

The thing is, not all of it really ran in order. I'd get working on a week and I'd be too close to a deadline and have to crank something else out which didn't end up in the book. It would totally throw people off. I tried to keep some sense of continuity, but some weeks it didn't work. I was really excited when I first self-published it, because people could read what I'd originally intended. Some people did and they were like, "This is great." So I knew it was okay after that. That was how I'd wanted to build the story.

Flagpole gave me a great opportunity. I'd like to thank Larry Tenner and Pete McCommons, the production guy and the editor respectively, who encouraged me from the beginning.

SPURGEON: You use a really nice wash effect, and even some color. Was

SPURGEON: You use a really nice wash effect, and even some color. Was Flagpole

able to handle that?

BAK: Everything looked like a gray-tone wash. They didn't print anything in color. They put the color strips on-line, so you could look at it there. Some people followed it that way, too. There was nothing printed in color. We ran everything as drawings. Even the color stuff looked like black and white wash drawings.

SPURGEON: The wash was really attractive, I thought; were they printed on nice enough paper it turned out?

BAK: It turned out OK.

SPURGEON: Were you ever worried about the production aspects of doing a work in a weekly magazine instead of in a comics publication of some sort?

BAK: Not really, because I knew it would get collected and published. I was like, "In the paper it can run like this, but when people want to see it full size..." This new book is almost to size; the originals are just a little bit larger.

SPURGEON: I want to ask you about some of your formal choices. I don't see a lot of cartoonists doing this, but you run text through multiple panels, not quite indiscriminately, but in a way that your panels are no longer discrete units. You'll start a sentence in one panel and end it three panels later.

SPURGEON: I want to ask you about some of your formal choices. I don't see a lot of cartoonists doing this, but you run text through multiple panels, not quite indiscriminately, but in a way that your panels are no longer discrete units. You'll start a sentence in one panel and end it three panels later.

BAK: There wasn't enough room in that panel!

SPURGEON: [laughs]

BAK: I wanted to have the juxtaposition of that visual movement accompanying, for lack of a better word, a lyrical kind of flow. One holding the other's hand through the narrative. I was aware of how I was going to do it, but I let it happen pretty naturally. I felt pretty instinctive about it. It happened naturally, but I knew that's how I wanted it to go. When I had that form to follow, I let it flow out that way.

SPURGEON: You use a lot of different visual approaches page to page. One page is a suite of panels, others have continuous backgrounds. Did that also flow organically?

SPURGEON: You use a lot of different visual approaches page to page. One page is a suite of panels, others have continuous backgrounds. Did that also flow organically?

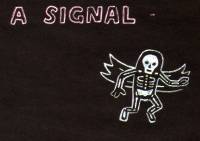

BAK: I wanted to do as much as I could but I wanted to maintain some consistency of the mood, and my own iconography, thematically the same ideas. One thing that was kind of a challenge is when I started working in the negative, the blacks, with kind of an inverted approach. I didn't turn that around, that was drawn on black paper with colored pens. I knew when I started doing that I was like, "I'm getting near the end," because the style was changing into something else. I wanted to see it all the way through, but when it was finished it was finished. I was like, "I have nothing more to say about this." I had fulfilled what I intended. But there are a lot of playful elements I'd like to return to, the submarine with the characters in there and the little ninja-bats and robots and stuff.

SPURGEON: On those black pages you're a lot more verbal. It has a "furiously written essay" feel to it more than a comics feel. That kind of text-heavy shift isn't something that most cartoonists are comfortable doing. Were you worried about loading up on the text part of it, or is that another thing you felt was needed?

SPURGEON: On those black pages you're a lot more verbal. It has a "furiously written essay" feel to it more than a comics feel. That kind of text-heavy shift isn't something that most cartoonists are comfortable doing. Were you worried about loading up on the text part of it, or is that another thing you felt was needed?

BAK: I felt it was all part of this narrative, and I knew there were symbols I could count on when I was on my soapbox. I knew I could throw them in there to get the idea across and it was something I wasn't going to rely on for the rest of the strip or the rest of the book, but the emphasis there was on the text, and I wanted to keep the visual symbolism very simple.

SPURGEON: One of your more striking icons is the skeletal angel. Where did that come from?

SPURGEON: One of your more striking icons is the skeletal angel. Where did that come from?

BAK: That originates in a movie called

The World According to Garp, based on

the John Irving novel. In the movie, Duncan, Garp's oldest son, runs around on Halloween in this costume, and the youngest son, Walt, who's dressed as a bear, is telling Garp how bears aren't afraid of anything except death, and then he dies later on. There's this foreshadowing with Duncan following Garp and Walt around and jumping out and scaring them both at some point.

I'm also referring to

[Jose Guadalupe] Posada, the Mexican printmaker from the late 19th Century, who used these types of skeletons and

calaveras in so much of his work. To me, that icon enabled me to have this visual representation of something that was culturally significant to me but also referred to these other ideas of the disguise of death, how life and death are aspects of the same thing. The figure of death moves through different aspects of the work. That was something I wanted to play around with. I'm probably too ambitiously philosophical.

SPURGEON: There's a real ruminative quality to your work in that you're continually processing things that have happened to you. In the black pages suite, there's this death motif, and the concerns of the strip seem more immediate than reflective because of it. In general, when you hold this work in your hands, do you look at what's been collected as a satisfying statement? Do you feel it was worth working through the issues involved?

BAK: I know that it is for me. Thematically, the work for me is about making sense of things on your own terms. That's basically what I had moved towards. When I was able to get that out, for me, there was kind of a catharsis to it. It made me feel... it lightened my load a bit. I felt this was something I was compelled to do, that I needed to do, that I needed to get it out there. I still do, I still want to see what else I have to say. It's a process, something I'm continuing to figure out.

SPURGEON: There's definitely a closed circle aspect to this book. This seems like something that you can both stand on and do new work as well as return to if you wanted later on. Speaking of which, what do you have planned? Are you ever going to do that project you talked about where you go to various cities and speak to people in the service industries?

BAK: Not right now, but I was going to go down to Georgia, there's an exhibition in Georgia, a comic exhibition I was recently invited me to. I won't be able to make it, but I'm going to do

a signing at Giant Robot in New York. Then I'm going to come back here and Randy Chang of Bodega and I are going to

Expozine in Montreal. I'm going to do some small signing events, including Giant Robot on the 20th. I may go back to Georgia later.

SPURGEON: Were you happy with the way the book turned out in terms of the production and printing?

SPURGEON: Were you happy with the way the book turned out in terms of the production and printing?

BAK: Yeah. There were some minor issues that came up. Randy and I were both stressed out about it at first. Then when I saw it, I was like, "We have nothing to worry about. This is fantastic." I think it looks swell. If it gets reprinted, we can fix a couple of colors. But otherwise, I think it turned out fine and Randy does, too.

SPURGEON: Other than the student strip, what's next comics-wise?

BAK: There's a

Drawn and Quarterly Showcase in the spring of 2008. I have a story in there. There's

Orchid 2 which is going to be maybe sometime next year. But my piece was finished two years ago, so now I kind of want to re-draw it.

SPURGEON: Eric Reynolds says he's been dying to get you into MOME. Will that happen?

BAK: Hopefully I can start on something by the end of this year. I do have a secret project that I'm working on, but I just had a sketchbook stolen from me with a lot of my ideas and stuff for that. I couldn't even draw for a week. I was like, "Holy shit." I kept calling the bus station and they were like, "Nobody's turned it in, sorry!" It's been over a week since I lost it and I know I've gotta let it go. It really blows. There's that. Before I left Portland I signed a contract with an agent who'll be pitching a graphic novel project to publishers early in 2008, so I'm working on that, too. It's an autobiographical examination of memory based on the story of

Orpheus and Eurydice, and like

Service Industry goes back and forth between different stories.

*****

* cover to the new book is at top

* all other art taken from

Service Industry interiors except for the

Orchid page, which is the fourth image counting down from the top

* as is usual, all copyrights to Mr. Bak or the appropriate copyright holder

* Mr. Bak would like to emphasize that we were kidding about Drew Weing and Eleanor Davis being jerks; they are indeed swell people

*****

Service Industry, T Edward Bak, Bodega, over-sized magazine format, 32 pages, October 2007, $9.95.

*****

******

******