Home > CR Interviews

Home > CR Interviews A Short Interview With Frank Santoro

posted January 25, 2008

A Short Interview With Frank Santoro

posted January 25, 2008

*****

Frank Santoro's

Storeyville may be the book of 2007, which is doubly amazing when you realize that it may have been the book of 1995 as well. Back then it was a haphazardly seen but much discussed tabloid newspaper by a maker of splashy mini-comics about whom little was known; today it's an over-sized hardcover from the boutique publisher

Picturebox Inc. by an artist about whom we're still eager to find out more. The story of a drifter who longs to re-ingratiate himself with a treasured mentor that slips ever so quietly into becoming a story about someone who needs to be sought, what most people take away from

Storeyville is the evocative coloring and the deeply personal style of picture making and pacing which dominate throughout. Frank Santoro is used to walking in two worlds, coming back to comics from a place in the world of gallery art in part by reconnecting with the unburdened, unaffected art of the 1980s black and white crush. His comic book with Ben Jones,

Cold Heat, may not have sold enough to continue serial publication, but after startling readers all over its map it will once again have the chance to impress when a single volume collecting work printed and work yet to come is released sometime in 2008. I could have talked to him for hours. -- Tom Spurgeon

*****

TOM SPURGEON: You're in Pittsburgh now, right?

FRANK SANTORO: Now I'm in Pittsburgh.

SPURGEON: Is that an area of the country to which you have ties?

SANTORO: Yeah, I grew up around the corner from where I am now.

SPURGEON: How did you end up back in your home town?

SANTORO: It's a confluence of events where I was in New York working for this artists, this super big-time artist whose name is

Francesco Clemente. Then I quit. I stayed on while the new person came in, and then I wasn't focused on my job and I hired a goon who threw a painting out. It was under my supervision so I got canned. It was a horrible situation. I had this super cheap sublet forever, for like five years while my friend went to

LA. It was downtown, $200 a month, for a tiny little room. But it was perfect. That dried up. All these things...

Then my uncle in Pittsburgh was like, "I'll sell you my house for a dollar." "All right." He was sick of paying the taxes on it. So my girlfriend and I moved to Pittsburgh. We said fuck it, and took a break.

SPURGEON: How is Pittsburgh as a town for an artist?

SPURGEON: How is Pittsburgh as a town for an artist?

SANTORO: It's different than it used to be. I remember the old days. It was really hard to be an artist, getting spit on and beat up at school. For having dyed hair or being an art fag or whatever.

SPURGEON: I spent an afternoon in a shopping mall south of Pittsburgh and came away with the feeling that our nation will never be defeated in war, just for all the uniformly buzz-cut, muscular, slightly psychopathic-looking guys everywhere. Everyone looked like Shute from Vision Quest.

SANTORO: There's counties in Western Pennsylvania that are number one in terms of enlistment in the army, and also in the amount of deaths. Pittsburgh itself is different because it's this

Rust Belt Detroit-like thing in the city. It was Italians, Irish, Polish and Blacks. That's it. My dad's Italian and my Mom's Irish, and that was like a scandal. The Italians are the on opposite side of the tracks with the blacks. The Irish were on the other side. My godfather was black. He lived down the street. It wasn't like my uncle or somebody who was my godfather, it was a neighbor. He was awesome. It was a real degraded mill town city. The '70s in Pittsburgh were great because the mills were pumping and there was a lot of money in Pittsburgh. When Reagan came in, it was all over.

SPURGEON: Has Pittsburgh done that thing where they emphasize the arts to try and move out of a decline caused by loss of industry?

SPURGEON: Has Pittsburgh done that thing where they emphasize the arts to try and move out of a decline caused by loss of industry?

SANTORO: Kind of, but it always had this cultural center because of

Carnegie Mellon and stuff like that. So there was a lot of art stuff in Pittsburgh. That was my saving thing because I took these classes at

the Carnegie museum on Saturday mornings ever since I was a little kid. That just sort of grows into these sort of pre-college high school programs that kind of set you up for school. And then I went to an arts high school, where I had art every day from 12 o'clock on.

SPURGEON: I'll stop asking questions about Pittsburgh soon. [laughs] I guess I always loved the look of these tracts of row houses that you'd see up on the ridge. They looked like they'd been there since the 1870s -- not just been there, but had been punished every day.

SANTORO: That's my bread and butter, though. As an artist. There's this

Faulknerian... that famous advice he got from

Sherwood Anderson, that the postage stamp of the land where you're from is more valuable than anything else. It can sometimes be a crutch, but Pittsburgh is this really easy landscape in which to situate every narrative kind of thing I've ever done. It's easy.

SPURGEON: Storeyville

starts there.

SANTORO: Yeah.

SPURGEON: How does it feel to have that work back in printed form?

SANTORO: It feels great. I think it's aged actually kind of well. I don't think it could have come out even two years ago.

SPURGEON: How so?

SANTORO:

SANTORO: It took until 2000 for

Jimmy Corrigan to come out and turn people's heads a little bit about comics in a larger, broader sense. For me, it's like most comics are pretty narratively tame. And then you have straight-up art comics like

RAW or something. In terms of just turning a story inside out and doing something different with it, the same narrative "strategies" are still employed. For

Ninja to come out a year ago, and

BJ and Da Dogs the year before, it just feels like the audience is changing. They've understood

Chris Ware and

Seth and

Chester and

Clowes. The broader audience I'm talking about. Everybody on the inside has known about it for ten years, but I don't think it could have been reprinted and had a mass push until now.

SPURGEON: How involved were you in the book's production?

SANTORO: Pretty involved.

Circle and Square and

Dan designed it, and we were all sharing an office.

SPURGEON: I'm sorry you had to share an office with Dan. [laughter] That must have been a horrible thing.

SANTORO: That was fun. We tried to do the bullpen, actually. It was cool. It was this fantasy I'd had. It really helped a lot for a million reasons.

SPURGEON: Quite obviously, the new Storeyville

is an over-sized book, whereas it famously had its origins as a tabloid. That would probably be the way that most people would describe it -- the tabloid comic that Sirk fella did back in the '90s.

SANTORO: I wanted that. I definitely cultivated that. I could put it out as a tabloid again, but I already did that. I wanted to try something different, reach a different audience and a broader audience. Giving it away for free after we sold as many as we could at

Green Apple in San Francisco or these great movie theaters that were around. I literally met people who said, "I found that on the bus. It was great! I read it. It was awesome." To me that was really exciting. That was the mid-'90s when you were just dying for comics to be in bookstores. How can we get them out there? What can you do? It felt like a whole different approach. I couldn't afford a nice hardback volume or even an over-sized volume. I could just do newsprint.

SPURGEON: But now the game has changed.

SANTORO: [laughs] We're still not making any money on it!

SPURGEON: Or maybe the game hasn't changed so much.

SPURGEON: Or maybe the game hasn't changed so much.

SANTORO: I don't think it has. For me it's gone full circle, for a lot of different reasons. It was Chris Ware that suggested it. He suggested it somehow in passing, in a letter that I had exchanged with him. "Why don't you do a nice, handsome volume of

Storeyville with some of your old mini-comics in the back." I thought about it. I mentioned it to Dan, and I think I had already done

Chimera and

Incanto at that point. It just didn't seem like the right moment. Something changed. The more we talked about it. Once we secured -- secured sounds horrible [laughter]. Once Chris agreed to do the intro. That's the reality of the situation. Chris's name on something... I shouldn't even be saying this, but his friendship,

Storeyville wouldn't exist in this form without Chris's friendship.

SPURGEON: That introduction he gave you is pretty remarkable. How did you feel reading it?

SPURGEON: That introduction he gave you is pretty remarkable. How did you feel reading it?

SANTORO: It was an e-mail or something, and I remember printing it out and going for a walk and sitting by this dirty canal in Brooklyn. I was stunned. [laughs] Ten years on, Chris is in a different place now.

It's so hard to explain. It was huge just to get his phone call in '95. I came home and there was a message from him for me. That was huge. We were pen pals for a couple of years leading up to Storeyville and to read that intro ten years on is just... I don't know. It's tender and kind of pulls at my heart, actually. I appreciated it more from the personal standpoint as a friend more than I did an endorsement of a book or anything. He really got me. Of anybody, he got it. And that's a big deal, feeling your work is understood, and especially by somebody of that caliber. I mean, Chris knows comics. [laughs] That was a huge thing. I'm kind of speechless about it, but I'm beyond thankful. I'm humbled by it, and I know that sounds corny. It feels great.

SPURGEON: When you say that Chris "got" you, does that mean you feel your work has been misunderstood?

SPURGEON: When you say that Chris "got" you, does that mean you feel your work has been misunderstood?

SANTORO: Oh, for sure. I remember when I did

Storeyville, it was "You shouldn't do it like this, you should do it like

Rubber Blanket. Have you seen

Rubber Blanket? Check this out." Or "If you could just tighten up your drawings." Everybody had something to say as opposed to, "Hey, cool comic." It was raked across the coals. Even

John Porcellino, we were exchanging letters. He was like, "I just don't understand it. I don't like the ending. I don't get it. It just ends." I remember

James Kochalka wrote me a letter and said, "It's too many pages; there's so much you can cut out." [Spurgeon laughs] That's fine, but I didn't invite that kind of criticism. I just sent it to people. You're welcome to criticize it whatever you want, but it was people telling me what I should do.

SPURGEON: What do you think about the work invited so many prescriptive reactions?

SANTORO: There's a baroque craft [phase] that comics is in right now, it's like this mannerist style of painting. Like a painting done of The Goddess Diana in the hunt, some allegorical painting from the 18th century. If you know the symbols and the back story and the way it's drawn and the referenced this artist making to maybe to an earlier work that's of a similar vein, it means something to you. Otherwise it's just something in the Met. It's a landscape with Diana in it. That's what comics is, it's so much about being this coded symbolism in drawing and rendering and all the little marks and shading. You have to have the same style from the beginning of the book to the end of the book. This uniformity.

I never understood that. I never strove for that, really. Whatever the scene dictated, whether it was a painting or a drawing or anything, you always just tried to pull out the feeling and the meaning of the piece through the media. I saw comics as the same thing. You can have some pencil and some charcoal and some paint and some ink and some

Zip-a-tone and whatever and mix it up and match it up and see what you get. But people were like, "Why are your backgrounds in pencil? You didn't ink your backgrounds?" It was ridiculous the things that people were saying to me. There was this standard to be adhered to or something.

SPURGEON: Where does that come from? Is it just that it's a highly commercialized art form? Is it a creative culture thing where people feel you have to do A and B to find success?

SANTORO: That was the mistake I made after

Storeyville. I tried to tighten up. It's good work. Everybody was like "Hey,

Storeyville looks good. Let me know what you're doing next." It was encouraging. I did try. I didn't know what

Brian Chippendale was doing. If I had seen what Brian was doing in '95, I would have felt galvanized by it. SF was different. My peers in San Francisco were like

Steve Weissman;

Ed Brubaker was around, he was friends with Steve.

Mats Stromberg,

Dylan Williams,

Jeff LeVine. We were all doing really different stuff and everybody was encouraging of each other. I felt a little more outside. They're cartoonists. When

Adrian and Dan Clowes and

Richard Sala would get together, I remember

Ariel Bordeaux's birthday or something, and they're all drawing. They're all cartoonists, they can just draw and draw and draw in this particular way. I can't. I'm not saying that one's better or worse. I remember feeling jealous I couldn't draw like that. Just watching them crank stuff out on a jam drawing, it was pretty amazing.

I didn't feel like there was much I felt a kinship with. They were friends of mine, of course. We were all doing our things. Everybody was doing such different stuff. Everybody was doing such different stuff. Everyone sort of let each other alone, it was this period where you could sell stuff to

Comic Relief, and put out a cool mini and a couple of things, and maybe you'd get into

Drawn and Quarterly or something like that. What else was there really to do? I had friends that were working for

Marvel, my friend

Ricky Mays did work with

David Mack on

Kabuki. He was part of

Gaijin Studios in the early '90s. So I had friends who were doing a lot of professional stuff. I don't know if that was option for me.

I remember I had an interview with

Disney in the late '90s. I knew somebody that knew somebody and I got an interview. I could do the drawing but I didn't go through their animation school, so they told me to go back to school. I was going to try anything just to keep drawing. There was no money in comics. Not that there was no money in comics, but people were encouraging about the work, but there was nowhere to go. So you do your minis, you do your 'zine, and you do your thing. It was great. I miss it. All the distributors changed. I sold 1000

Storeyvilles without even trying. It was a whole different world.

Capital was still around.

Bud Plant... I could sell to three or four different distributors at least.

The tabloid I thought would work because I could get on these newsstands. But the newsstands told me they wouldn't carry a comic book. I was like, "It's a tabloid." They were like, "We don't care. We don't carry comic books." Even if I could have done another

Storeyville, I wouldn't have had the money.

It was fine. I started doing book fairs in California. People would be selling art, also. I was selling some small paintings and then some collages, and it was easier to sell a small painting here and there than it was to do comics. Which I think is a pretty common story. I had friends that worked in galleries in New York and I just moved to New York. I worked for a lot of really great galleries, and then got this great job with this artist who was one of my favorite artists when I was in school. That was five years of hardcore Art with a Capital A. I got to go to a million different places and meet a lot of interesting people. It was an eye-opener in terms of broadening my artistic vision of something. It was great, but it was a whole different world. That was a learning curve, too. There's definitely money in it. People would buy your work, but they weren't really interested in your work. They were hedging their bets. They thought, "Okay, maybe this kid will become famous down the line, so I'll buy his painting now for this much." Whereas in comics there was a more honest feedback and interest in your work. That was great.

I really owe it all to Dan [Nadel]. If I hadn't met Dan, I don't think I would have come back to comics.

SPURGEON: What about your interaction with Dan re-sparked your interest?

SPURGEON: What about your interaction with Dan re-sparked your interest?

SANTORO: We just became friends.

Bill Boichel of Copacetic Comics told me about

The Ganzfeld. He thought that Dan's in New York, and here's this interesting magazine that's sort of this intersection of art and comics. Maybe this was a good forum for me. So I took a look at it, and wrote Dan a letter. Dan knew my work. He knew

Storeyville, and that was great. We met up for beers and we started talking about

Kevin Nowlan comics and shit like that. It was pleasant. Dan became this really good friend. We would go to

Time Machine, this great comic book store in New York, and buy old

ACG comics. It was fun. Art's so serious sometimes, and comics are a release from that. That was the big thing.

So many different things happened in those short years. He got this grant. He published

BJ and Da Dogs. He went from doing

The Ganzfeld to doing all these different projects, which is awesome. There's finally a publisher more towards my sensibilities. Dan's got a really sharp eye. There was a pile of

Kim Deitch drawings at MoCCA, because you know Kim carries that briefcase around. I looked through that fucking briefcase, and I thought I got a really good one. And then I saw the one Dan pulled out. "Where did you get this? This is the best!"

SPURGEON: I hate people like that.

SANTORO: I passed it right by, and he nabbed it.

SPURGEON: Is there editorial back and forth when you work with Dan?

SANTORO: For sure. He's a great editor, too. Every artist has these weird temperaments, and Dan can be very even keel at those moments. He knows what to say without forcing it. It would be more like a coach and less like an editor, because he's able to coach all these different personalities through their process. Everyone from

Marc Bell to Ben to myself. We all struggle through shit at times. But in terms of Ben and I doing

Cold Heat, not so much. We might show him some layouts and he'll comment. It's not until things are shaping up and there's a transition that doesn't work or something.

SPURGEON: How did your partnership with Ben Jones on

SPURGEON: How did your partnership with Ben Jones on Cold Heat

come about?

SANTORO: I never met Ben until

SPX 2005, actually. I went to

MoCCA in 2003 just because I was in New York. I bought a dog spraypaint print from him. That was my favorite thing in the whole show, this print that he had made. I bought a

Low Tide off of him I think. I didn't really know his work, and I wasn't really familiar with

Fort Thunder at all. Through Dan I got to know it, but in 2003 I didn't know it. In 2005 I met Ben and

BJ and Da Dogs was just about to come out. I don't know. We both had ties in Pittsburgh, so we were talking about Pittsburgh. The real idea were these vague things that had been kicking around for both of us and then just united. I wish I could tell you. It was this vague, insane thing and the one day it's this girl ninja comic. [Spurgeon laughs] I wish there was this secret history it. I wish I knew. By the end of January 2006, we had the first issue laid out and ready to go.

SPURGEON: Is there anything about the way you two work worth noting?

SANTORO: I think a lot of people think about what he's drawing and what I'm drawing, and I'd like to keep that mysterious. But there's definitely tension between his layouts and my execution. That's the real tension. His pacing is just impeccable and the way he organizes a page is subtle and dead on. He gives me cushions to speed things up or slow things down and room to organize my own transitions, but for the most part he's shaping the script and talking about the script, and then he's doing these layouts and then I send my version back, and he sends those back. We go back and forth. A lot of the layouts is this tension between Ben's skeleton and my skin.

SPURGEON: Were you surprised by the reaction that the book got? There was an expected reaction where people freaked out and didn't know what to do with the art. There was one retailer who described it in absolute negative terms.

SANTORO: Brian Hibbs was the guy who told me I had to do

Storeyville like

Rubber Blanket. [Spurgeon laughs] I went into the story and I was like, "Will you sell

Storeyville?" And he was like, "Look, you can't do it like this, you gotta do it like

Rubber Blanket. This is what will sell." He's right. He's a smart guy. He's a retailer. But it was this "Don't do it like that, do it like this" again. When he said "This is the most unprofessional comic..." or whatever, I kind of relished that.

SPURGEON: Wizard

reviewed it positively, Diamond was carrying it for a while... there was an element of acceptance.

SANTORO: Sure. I think a couple of blogs came out for it. Jog wrote an early great review of it, and there was one in the

Journal. It's funny how people were defining it. We never set out to do an action-adventure thing. We didn't sit down and say, "Let's do an action-adventure take with an art comics spin." We didn't set out like that. It sounds so corny, but it was genuinely sincere. This is what we want to do. I'm surprised by the reaction where people are like, "I can't stand the way this is drawn. It's horrible. It's crude! You can't do this." Obviously these people have never seen any of the comics from the black and white explosion like

Shuriken or

Ninja High School. There's so many comics that are the most retarded comics of all time that are great for their own reasons.

I think with

Cold Heat we're trying to go through our influences. Everyone in alternative comics is trying to go around this behemoth of 20th Century comics and what 20th Century American comics are. We're going right for it. Right through the heart of it. Right to the other side. You get to use all of your influences, and all of these things that inform you, turn them inside out and just open the throttle and go. Without any hesitation. For me, that's what

Cold Heat is. It's supposed to be fun. I'm kind of quoting Dan. "Do we have to have this 'Can

Gary Panter Draw' argument again?" I'm not comparing myself to Gary, but so much of comics criticism comes from the person's ability to draw a particular style that acceptable to a certain element of the audience. It's not so conscious but when that reaction comes back it's funny. I'm having fun.

SPURGEON: Remind me of the status of the Cold Heat

collection.

SANTORO: It will come out this summer. 240 pages. The binding will be a bit like

the Yokoyama book.

SPURGEON: Does removing Cold Heat

from serialization affect your process at all?

SANTORO: We opened it up. There was a possibility of doing longer chapters because there were a few issues at the end that weren't scripted. We could change it, but we decided no, we'll just do it as originally planned. It's awesome: 24-page installments. I'm really bummed about this. [laughs] I've always wanted to be a regular comics artist. I'm super-bummed that for all these stupid factors it couldn't have happened.

SPURGEON: Is there anything other than the obvious, that it didn't click with an audience?

SPURGEON: Is there anything other than the obvious, that it didn't click with an audience?

SANTORO: I think it could have clicked with the marketplace, but you have to wait until issue #6 or #7 to know what the numbers are. We probably should have put out a graphic novel to begin with, but somewhere you have this secret hope that somehow it's going to catch on or something. Dan, God Bless him, he took it on the chin for four issues and then he was like, "Look, we can put out a really great graphic novel. I can keep doing this, but that just means the idea of a collection or anything extra will be impossible." He was like, "There's this much money left in the budget for this project." And I agreed. It didn't make sense to put it out as issues and people see it here and there and they're going to want a collection anyway and then we're not going to be able to collect it.

It's just hard. It's just a bummer. The market is so different than when I was growing up. I grew up basically in the black and white explosion, and I saw everybody doing comics, and everybody selling comics. You'd go to cons when you were a kid and everybody had some sword and sorcery character they were making a comic out of. You know? Not that that was what I wanted to do, but it was an exciting time in terms of you doing it yourself. I'm such a huge comics fan, I even talked to David Mazzucchelli. "How can I do it? Can I actually do it? What does it take?" He was giving me words of advice. I was excited about the prospect of doing it for a year. I have a completely different appreciation for

Guy Davis, Kevin Nowlan -- Nowlan's not usually a regular book guy, but all the guys who do regular comics. I think that's really more comics than Dan Clowes or Adrian Tomine and 36 pages every year and half. Comics to me is 24 pages a month, bang it out and get it done. That's comics. The other thing is graphic novels.

SPURGEON: Is it something about the quality of the art that comes through when you're doing it that quickly?

SANTORO: Cold Heat #4 was everybody's favorite so far, but that was the one on which I spent the least time. By issue #4 I got it done in 30 days, on schedule. You channel this whole different work ethic than when you're making

Storeyville. You know what I mean. I just read

Adrian [Tomine]'s book. It's awesome. It's airtight. It's perfect. But it's a graphic novel. It's not a comic book.

SPURGEON: I get you a little bit. There is something that's very affecting, a kind of fundamental sense of the medium when someone's working quickly. Even the junkier black and white stuff.

SANTORO: I have a lot of that stuff. I really cherish it. It's such a different animal. I wouldn't call it great art.

SPURGEON: There's a definite quality when a guy is trying to create this entire universe in 24 pages. If you reduce it, you could see those guys as Lords of their Universes, and what you have now is a bunch of folks trying out to do the next children's book adaptation at Scholastic.

SANTORO: My friend

Jim Rugg of Street Angel fame is, well, I wouldn't say struggling with that right now but he’s in a weird place and I fell for him. He has this audience that loves

Street Angel, but he's like, "I've met every

Street Angel fan." He's doing some inking jobs for DC and they pay, and I understand what he needs to do. He sees doing

Street Angel as a lot of labor and not enough to live off of. But if he does these inking jobs he doesn't have enough time to do

Street Angel on the side, so he's pitching these other projects. And I hope he can make that work. It seems really precarious.

On the other hand, there's my friend

Tom Scioli who does Godland who works a full time job and pencils

Godland. I couldn't do that. That's why I moved to Pittsburgh, to live cheaply while I finish my graphic novel. Nobody's getting rich off of this stuff. Tom is doing a comic book. The book comes out regularly. He's going for it in this particular vein. It's like a conceptual art statement that he's making. And Jim... I see what he's trying to accomplish, I really do. But I don't have those kinds of chops. He has a great hand and he can get jobs doing the jobs he wants to do beyond the characters he wants to do . I don't think I could be less idiosyncratic than I am. I would love to do

Cold Heat where it came out regularly and had an audience and had spin-offs, but it's not 1988 anymore. Did you know that for the first issue of

Yummy Fur, 10,000 copies were printed?

SPURGEON: You can argue a calcification of the market away from a loose, rambling system in the late 1980s where you could move a lot more copies than you can now, at least until that system was abused.

SANTORO: I've been around comics enough I've seen it come and go. I was always involved even when I wasn't making them. I'm interested in the form, but once the illustration jobs dried up -- my friend

Marc Weidenbaum at

Pulse was really great -- those were the things that got you through back then. But by the millennium people weren't using illustrations anymore, you're not in your 20s anymore, and there's mini-comics, but to me a lot of that was old hat. It wasn't anything exciting.

SPURGEON: You sound like a man who can see his own exit. A man who can see the end game.

SPURGEON: You sound like a man who can see his own exit. A man who can see the end game.

SANTORO: I don't know. Maybe. What does that mean?

SPURGEON: That you can see a day where you might not be doing comics to the extent you are right now.

SANTORO: Maybe. Not necessarily.

SPURGEON: [laughs] I could just be wrong, Frank.

SANTORO: It's just that I've been through it once before. I feel like I'm still pretty idealistic and hopeful, but I'm not naive anymore about the numbers. That's not what's keeping me away from a commitment to it. It's a pretty crazy life to be a cartoonist. It's hard. It's a whole different world. It's a whole different world. Every comic artist will say that. It's a lonely life.

*****

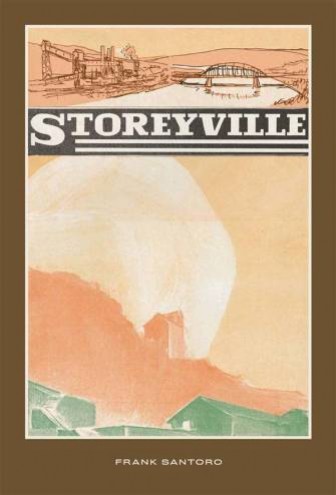

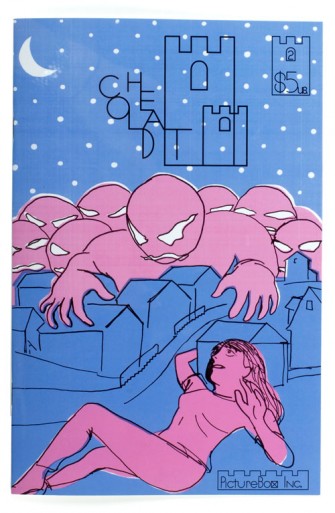

* cover to the new PictureBox Inc. edition of

Storeyville

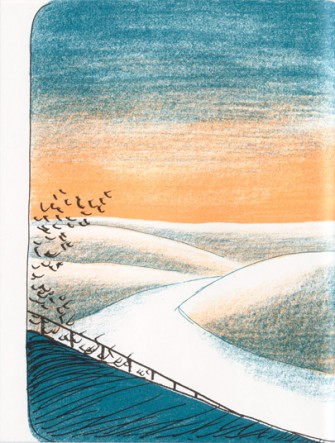

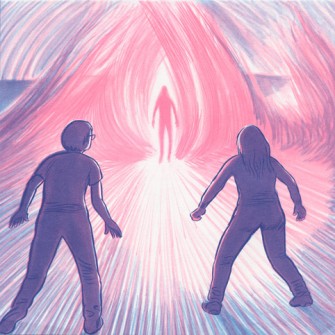

* interior image taken from

Storeyville

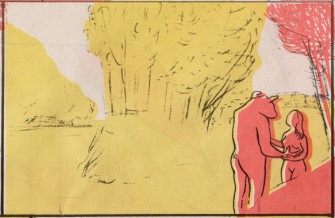

* 2005 collage and marker work by the artist

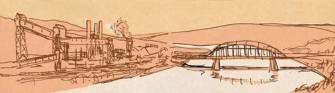

* interior image taken from

Storeyville

* an image each from

Incanto and Chimera

* cover to the original tabloid version of

Storeyville

* a strip of art from

Storeyville

*

Cold Heat print by Ben Jones and Santoro

*

Cold Heat #2 cover

* two interior images from

Cold Heat

*****

*

* Cold Heat #s 1-4, PictureBox Inc., $15.

*

* Storeyville, PictureBox Inc., hardcover, 48 pages, $24.99

*****

*****

*****

the CR Holiday interview series continues through Monday with two interviews scheduled for each day. Tuesday, January 8 marks a return to this blog's full array of regular features. We thank you for your patience.