Home > CR Interviews

Home > CR Interviews CR Sunday Interview: Matt Madden And Jessica Abel

posted June 30, 2012

CR Sunday Interview: Matt Madden And Jessica Abel

posted June 30, 2012

*****

I interviewed cartoonists and educators

Jessica Abel and

Matt Madden a few years ago for their first comics textbook

Drawing Words And Writing Pictures. I received an "incomplete," having recorded the piece in a way I couldn't retrieve its content. I'm grateful for this make-up opportunity on that book's sequel,

Mastering Comics. As we dicscuss below, the second book is a much more complicated beast than the first, engaging a variety of aims without much of a road map in terms of what a second book of this type might do. It's hard to imagine a more substantial, serious effort, and I think it should be obvious they've more than achieved one of their goals: to create a book that can be taken off the shelves and accessed for several years.

Mastering Comics is also a book from which people without any desire to do comics may learn, which I think is a remarkable feat. I can't imagine this particular assignment falling to a more capable pair. -- Tom Spurgeon

*****

TOM SPURGEON: Am I right in thinking that you guys were going to move at some point? Did I miss that?

TOM SPURGEON: Am I right in thinking that you guys were going to move at some point? Did I miss that?

JESSICA ABEL: You haven't missed it yet. In August, we're moving to France.

SPURGEON: Wow. Well, that's nice. [slight pause] I hope that's nice.

ABEL: That is nice. It's scary, but it's nice.

MATT MADDEN: We're doing the residency

at Angouleme at the Maison des Auteurs. That's this program they have... any authors that publish in France can apply.

Sarah Glidden is over there right now, and

Nathan Schreiber. Do you know him?

SPURGEON: I know Nathan a little bit -- more like I know of

Nathan. I knew Sarah was over there for some reason, but I wasn't sure what for.

MADDEN: This residency has been around for about 10 years or so but it feels like it's only recently been discovered by people in the U.S.

Ted Stearn is going to be there for a little while, overlapping with us.

ABEL: Another cartoonist,

Jeremy Sorese, introduced himself to me

in Chicago at the comics thing, but I had to run away so I didn't really talk to him. He'll be there most of the time we're there.

SPURGEON: Will you have duties you're expected to perform?

ABEL: We have to present our work at the end, I think. We'll probably do a couple of public talks. There's not very much in the way of requirements.

SPURGEON: This book is very, very impressive. I have all sorts of nerdy book questions. The first one obviously is what was the reaction to the first book that drove the conception or idea of doing a second one?

ABEL: That's a slight misunderstanding of how the second one came about. Originally the first book was going to be 30 chapters long. We realized somewhere in there that that was a really stupid idea. We proposed to First Second that we split it in half. They were like, "Great. That sounds fine."

MADDEN: A lot of it was a done deal before the first book was out.

ABEL: The conception was a done deal, the book wasn't done by a long shot. The idea of "here's what the second one will be," changed a little bit, but we pretty much knew what we wanted to cover in the two books from the beginning.

SPURGEON: One thing that's interesting to me about the two books is that the distinction is made between basic class and advanced class instead of, say, "craft" and "story," or all the other ways you might have been able to break it down. Whose idea was to break it down in that fashion?

MADDEN:. That's a really good point. We didn't initially talk about "here's the craft book and here's the story book," although that is one way we've talked about the difference between the two, certainly. We've struggled a bit with trying to figure out how to talk about this new book in a cohesive way. It kind of goes all over the place and covers a lot of different bases. It's advanced for us as writers. [laughs] Advanced book writing.

DW&WP is pretty straightforward. It's literally by the numbers. There are 15 chapters and we walk you through a lot of craft, the fundamentals of storytelling, the language of comics. It certainly has its tangents and divergences as well, but it's pretty straightforward.

Mastering Comics is no longer obviously a straightforward path. It's more meandering, and there are multiple streams: the idea of professional practice, and getting your work published and seen, along with how to do perspective, and how to do coloring in Photoshop and by hand, all the while talking about finding your voice and developing longer works.

ABEL: In the first book, we do talk about production. We try to always keep a focus on the idea that you're producing this with an eye towards reproducing this. Always. From the very beginning. Maybe not the first four or five chapters but as soon as you get into any kind of layout and inking, you're talking about making a book, right? That's already a focus. We know very well from teaching students who are in their first year of learning comics, that's as far as they're able to conceptually go. Making a minicomic at the end of doing a bunch of comics is tough the first time you do it. We want to say it's a great ending point for you; we wanted that first book to be achievable and dominatable. People can do it and learn it and really, truly master it -- unlike the second book, which is not about

finishing mastering it but

continuing mastering it. [laughter] But you can master those beginning skills.

When you've moved on, and you're doing some deeper thinking about comics: you've self-published in one form or another a few times, you've seen how it works, you figure out the difference between an original and a reproduction, you're able to conceptually broaden your idea of what you're doing to include all different kinds of production and career concerns as well as broader artistic matters.

SPURGEON: Is that what makes this more difficult, then, that you have more concerns, more to grab onto? I'm kind of after what makes this less straightforward -- is it just that there's more to cover?

SPURGEON: Is that what makes this more difficult, then, that you have more concerns, more to grab onto? I'm kind of after what makes this less straightforward -- is it just that there's more to cover?

ABEL: Fewer answers.

MADDEN: There are fewer straight answers. We talk about inking and using pens and brushes. In the first book, it's like, "Here's how you hold the pen. Make sure it's pointing this way. If you can't get the ink to flow, trying shaking a bit out on the paper and dipping into the blob. Draw straight lines. Draw diagonal lines." It's very clear stuff and you can say this is how you do it and this is right or wrong. This will work. This won't work. In the second book, we have more tool stuff -- like using q-tips and fingerprints for inking -- but we're also talking about how to use different inking styles to express mood or the subjectivity of characters in your work. We show a lot of examples from our work and other artists, like the way

Joann Sfar shifts registers from realistic to doodly on the same page or the way

Jaime [Hernandez] spots blacks. None of these represent the "correct" way to do something, they're just examples of things that work.

ABEL: I wanted to add one thing to what Matt is saying. As sort of a clue to this, look at the critique appendix in the first book and the second book. A critique appendix is designed for classroom use or for group use so you have some questions to guide you when you're doing critiques of your work. In the first book, they're very detailed. "Here's stuff to look for, here's stuff to talk about." The second book is more like "Well, you know what you're doing. Talk about it. Have fun." There's a little bit of detail in there -- there are a couple of specific critiques -- but mostly there aren't any because there's very little we can tell you to say. It's all open-ended.

SPURGEON: When the first book got out there and you got to see how people were using it, how much did that have an effect on how the book was written? Were you surprised at all at how people used it? I know that you suspected certain kinds of use, but what was the reality?

ABEL: I think the one thing that was surprising to me, anyway, was how much interest there was from people that aren't cartoonists, on the literary end of things.

SPURGEON: In terms of getting a grasp of what's involved?

ABEL: Pepole really enjoying the book, getting a lot of out of it, understanding how comics work. I don't think there are a lot people assigning as a textbook for non-drawing classes, though there are some. That doesn't happen that often. But a lot of teachers are reading it and getting ideas for what they can incorporate into the classroom. A lot more of that than we realized was out there. We've become aware of this whole community of educators that are trying to incorporate comics in all kinds of classroom uses. It's not our main interest, it's not specifically what we're doing, but it dovetails nicely with what we're doing. It's definitely something that affected our thinking a little bit.

MADDEN: Basically we didn't change much. We weren't really able to accommodate certain things. One teacher recommended that the second book have less writing in it [Spurgeon laughs] because he saw his undergraduate students weren't necessarily getting as much from the writing as from the examples. Stuff like that. The amount of time you're likely to spend on a given page. Point taken. On the one hand you're like, "What, are these kids too lazy to read." But brevity is always good in an instructional book.

ABEL: We are not people who can speak briefly. [laughs]

MADDEN: We tried. We cut a lot of stuff out of this book. Every chapter has multiple revisions and edits. I especially am looking for ways to make it shorter and cut stuff out. Everything in there has to be there, I feel it's solid stuff.

Another issue is, and this one I feel really bad about but there's no solution for it, but we get occasional complaints from older readers -- and I'll count myself among them -- that the font is kind of small. [laughs] It's ten-point, or something like that. That's just a matter of how much stuff we need to fit in there.

ABEL: The cost would go up if it were longer.

MADDEN: It was too late to re-conceive the whole thing.

ABEL: There's probably more stuff about writing comics. We had that in there, but we did a little bit more on that and focused on that a bit more because of what people were interested in. Partly because it was already conceived when we did the first book, it evolved in an organic way. It's definitely not the same book it would have been if we had done it in 2008 or whatever. It's mostly a reflection of itself rather than the world.

MADDEN: People responded really well to seeing different kinds of art in there, which was something we were already doing but was an encouragement to do more in the second book: a lot of art in there, and a lot of different kinds of artists.

SPURGEON: It's very airy, with a lot of white space.

SPURGEON: It's very airy, with a lot of white space.

MADDEN: That's

Danica Novgorodoff -- she's also a cartoonist. She's the designer. When we first started doing

Drawing Words, she was the in-house designer at

First Second.

ABEL: She became the designer on

Mastering Comics freelance.

SPURGEON: Is there a reason you wanted it easy to read that way, or attractive that way, as opposed to making it shorter?

ABEL: I guess you could have smaller margins or something. I don't know how much shorter it could really be. The airy design is something we really like a lot. It's fun to frustrate cartoonists who are like, "My art could have been in there!" Mostly it just makes it pleasant to look at.

MADDEN: More manageable, too.

ABEL: It's inviting in a way. A book like this is hefty stuff; it's not a light-summer read. If you make it beautiful to look at, it's more tempting to get into.

SPURGEON: Do you have an editor, or do you do all of that yourselves?

MADDEN: We do that for the most part ourselves. For both books we had a kind of freelance editor/academic advisor. One was a college friend of mine named

Bruce Cantley who does textbook editing and copywriting and then another woman,

Mika De Roo, who's worked in that field before. They were doing close line-readings of our stuff for clarity. Neither of them are comics people. We wanted to have some eyes outside of comics geekdom, that wouldn't let stuff we take for granted slip past. Their background in editing textbooks helped us with organization, ideas on headers and subheaders, things like that. Early on we had a lot of back and forth.

ABEL: They both had a lot to say about content in terms of making things clearer. They had stylistic difference in terms of what they cared about, but they were really helpful in terms of helping us speak to everybody.

SPURGEON: The thought of doing something like this seems terrifying to me. You can't fudge your way through any of this. Was there any section where one or both of you felt inadequate, where you felt you needed to do some homework to do a specific chapter?

SPURGEON: The thought of doing something like this seems terrifying to me. You can't fudge your way through any of this. Was there any section where one or both of you felt inadequate, where you felt you needed to do some homework to do a specific chapter?

MADDEN: Webcomics is a big... an area that neither one of us has a huge amount of experience with. We had to do research on that. We had an intern,

Matt Huynh, who did a lot of research on blogs and articles and finding out what information and books there are about webcomics.

ABEL: Beyond that, just talking about various digital publishing platforms, how do you talk about that stuff?

MADDEN: Particularly in that it's still developing -- talking about tablets and smart phones and stuff like that. In that case we tried to say as little specific as possible. New things are happening so quickly that it seemed like were setting ourselves up if we made a definitive statement.

ABEL: What evolved out of writing that was just talking about "platforms": that's the way one talks about this. It's not saying, "This platform is what you want to do, and this is how you do it." Rather, we wanted to create a set of questions and concerns that could guide a cartoonist through assessing whatever platforms exist when they're reading the book. It was tough to come up with the way to describe that.

SPURGEON: Now how much of this is talking to your network of friends, how much is seeking out specific people? The conclusion on platforms, how did you get there?

ABEL: We both got there ourselves. It sort of comes out of the writing. The research is mostly on-line. We might ask a question via e-mail of somebody.

MADDEN: In general, we're always in dialogue with our peers, particularly the cartoonists we teach with at

SVA:

Tom Hart,

Nick Bertozzi and

Jason Little are people with whom we talk about comics.

ABEL: They weren't reading our drafts or anything.

MADDEN: No, but Nick Bertozzi and Tom Hart and I have talked quite a bit about digital platforms, and that has found its way into the writing.

ABEL: There's also conceptual stuff that we go over here, like narrative structures and what is a comic and closure... we both think that the

McCloudian definition isn't complete. How far do you want to go into the theoretical end of things? That's really challenging. And we had to negotiate each one of those things on its own.

I do most of the first drafts about writing and the narrative arc -- I drafted that and Matt gets into it later. We've been criticized for teaching the traditional narrative arc. But we feel you need to learn this. I understand the criticism, but the person that said this said "Why aren't they teaching modernist writing?" I feel students need to know what something is before they break it. The narrative arc is such a straightforward thing in some senses. Students understand it intuitively, but need to learn how to apply it to their work, and that's a huge, ongoing job. So I don't want to ask them to do a ton more than that initially, though of course I hope they learn to see its limits. That's a tough one.

MADDEN: Given my own tastes for work that is experimental and formalist, I feel a shortcoming of both books is they don't push the envelope as much as they could as far as the outer limits of what comics can do. I think we've done our best to try and fit it in various places and talk about that there are different ways to approach making comics. Again, it's a difference between talking about something in a practical way as opposed to the open-ended "well, try it and you can see." What's good and problematic about the narrative arc structure in screenplays and creative writing is that it's a system that is very clear and it has a formal structure to it that is very solid, actually, and it works. You find it underlying the vast majority of storytelling whether it claims to be traditional or not. It's straightforward to explain and talk about. Once you get off that path it's amorphous -- that's maybe even a later book. We haven't really figured out a good way to talk about it.

ABEL: We can do it on a case by case basis in a class, but how do you teach making experimental work? You can give a series of exercises, but you can't give rules: that's the nature of it. We talk about constraints and show how that works.

MADDEN: I think we did a good job of putting a lot of creatively challenging activities in the book. We have a poetry comics assignment, a portrait comics assignment, these are non-linear ways of approaching comics.

Mastering Comics is meant to be a practical handbook and resource. I get a bit wary when I see descriptions of the book that are, "Oh, their new book on theory and practice." It's not really a theoretical book. I would not want to submit this to an academic journal for review. It would get ripped to shreds. That's not our goal. We're not trying to present some overarching theory of how comics work and what they are. It's meant more as a resource for people to make stuff with. That's a very different set of concerns than a theoretical framework.

ABEL: The overlap is where it becomes difficult for us. Because you do need some of that stuff to make it work.

MADDEN: As a practitioner, I think everyone needs to know what the narrative arc is and how it works. No matter what art or narrative art you're doing. Even non-narrative art. It's a structural element in a huge amount of Western narrative art.

ABEL: And Eastern, too.

MADDEN: And Eastern, too. I think that's a principle as a practitioner, no matter what your end goal is, whether you want to be a screenwriter or whether you want to do non-linear poetry comics. Coming at it from a theoretical standpoint, you might throw it out from the get-go. That's an imposed structure from outside, and the author's intent doesn't matter. You're coming from a totally different academic standpoint. Maybe in context there's no need for something like talking about the narrative arc. It's a very different approach to talking about the art form.

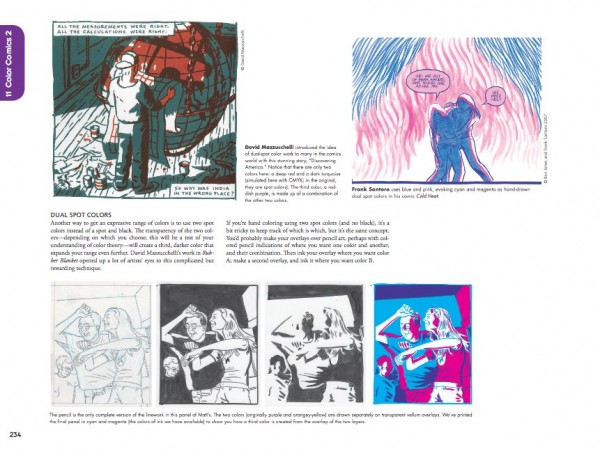

SPURGEON: How organic a process was it for you to collect and employ the samples you use? I'm looking at page 234, and there's a [David] Mazzucchelli and a [Frank] Santoro and bunch of panels from Matt. Do you have this at your fingertips?

SPURGEON: How organic a process was it for you to collect and employ the samples you use? I'm looking at page 234, and there's a [David] Mazzucchelli and a [Frank] Santoro and bunch of panels from Matt. Do you have this at your fingertips?

ABEL: It's very difficult, actually. It's very, very challenging. We do know a lot of the work. A lot of it is out of our bookshelves. But a lot of stuff isn't, and it took incredible effort -- mostly on the part of two interns,

Hilary Allison and

Li-Or Zaltzman with me -- taking trips to the library, scanning panels to try out, to see if this works or that works, to try and get a diversity that doesn't necessarily reflect our taste and our collection.

That particular page? Not that hard, right? That's an easy one [Spurgeon laughs] because if you're discussing Pantones you're going to put in "Discovering America."

MADDEN: The panels I did show the process, and Frank had done

Cold Heat pretty recently when we were working on it.

ABEL: Cold Heat we put in initially because I was under the impression that he was using Cyan and Magenta for it, but then Matt pointed out he was not. He was using Pantones that are sort of similar. It kind of undermines the reasons for using it. We used it anyway, because it was a nice panel. It's another nice panel. My hope was to print it in the original cyan and magenta and make it more of a transparent example, but that's not what ended up happening.

Look at the rest of the color comics section, and you get to stuff that was really difficult to pin down. Especially when you get to computer color. The hand-colored stuff, a lot of that's just out of our bookshelves. We just look through and think, "This is a good example."

MADDEN:

MADDEN: We have

a Mutts; I don't even know where we found that.

ABEL: Hilary found that in the library. Some of these are scanned from the books but in many cases they're originals from the artist. So tracking down Patrick McDonnell's studio, that was this incredible process.

On page 208, that

Dave Stewart panel, I was calling around and asking, "Who is a great semi-mainstream colorist we can use." So I asked other colorists, people at

Dark Horse and through that process I got in touch with Dave Stewart. He was recommended to me by other people, and he is really fantastic. Then I had to find something that showed what I wanted to show... it was really difficult.

SPURGEON: When the first book came out, that seemed like a heady time for comics art education. It seemed like there was a lot going on in New York publishing as well. Has the context changed for the arrival of this book?

ABEL: I think we're a lot more cautious now about what the outlook is. The recession hit just about when the book came out. The global panic was like three months later.

MADDEN: When were working on the first book and building up to it coming out, it was like, "Oh yeah, great times." We've never been jump-on-the-bandwagon, over-the-top optimists about stuff. I'm always aware that bubbles pop.

ABEL: And being an artist is being an artist. It's not easy.

MADDEN: Even in the best of times, being a creative person of any sort is an iffy proposition.

ABEL: But there were a lot more possibilities at that point.

MADDEN: Yeah. And stuff has scaled back a lot, so that has changed things. But on the other hand, I still maintain, and I don't think this is being overly rose-tinted glasses about it, that comics' status in culture, in North America, has reached an upper level that's it not going to come back from.

ABEL: Yeah.

MADDEN: That part is not a bubble that's going to deflate. People aren't going to stop reading comics that started reading them ten years ago when they saw Jimmy Corrigan at their local bookstore. There's an uptick in the size and variety of the audience that read comics and want to make comics...

ABEL: Look at this conference that was at University of Chicago just now, where 17 top cartoonists are on panels all day and all these academics are super-excited and it's a major, major event. It wouldn't have happened ten years ago. When I was talking to

Hillary Chute, she was saying that when she was hired four years ago the search committee said, "We've been interested in comics for over

ten years." [Spurgeon laughs] That's our time horizon. Comics are entering the academy like brand new, practically. It's happening all over the place. So it's an interesting and good time for comics education. Studio education is different, and we still don't know where that's going. But I think it is growing.

SPURGEON: What do you mean by "studio education"?

ABEL: Making them as opposed to reading them.

MADDEN: The study of comics sector of education is moving a lot faster than art schools or even community colleges are introducing comics-making classes in their art departments or creative writing departments. That's a larger goal of these two books, to provide ready-made textbooks and handbooks that teachers and students can use. So even a smaller college or art school where there's not a local famous cartoonist they can bring in to teach class, someone with a bit of gumption to give it a try, who appreciates comics even if they haven't made a bunch themselves, can use our books to teach class.

SPURGEON: Do you get any pushback from other cartoonists the way I've heard them grump sometimes, where they're like, "You can give them those two books, or you can lock them in a room with a pile of paper. They'll become a cartoonist or they won't." Comics has a long tradition of the opposite of these books -- the suck it up and learn it yourself school.

MADDEN: That's how we learned.

ABEL: That's exactly why we did these books. Because that sucked so much. It was so not fun not to know things and not know where to find out.

In terms of pushback, though...

MADDEN: Nobody's come up to us at a convention and said, "You guys are full of it. Why are you trying to teach people comics. You're giving away our secrets."

ABEL: When established cartoonists read it, there's usually something in there that's new for them. Not necessarily a lot, but ways of thinking they hadn't encountered before. It's like reading the mind of a different cartoonist. So mostly they like it for themselves, so we don't have a lot of problems with that. I'm sure there are people that are teaching a class and see the book and are all, "Hmm... I think I'm just going to use

Understanding Comics." They don't want to get on our bandwagon -- which I understand.

SPURGEON: Was there anything that was particularly gratifying to you to have out there?

SPURGEON: Was there anything that was particularly gratifying to you to have out there?

ABEL: All of it. [Spurgeon laughs] If I had had my book in 1991...

MADDEN: ... look out, world.

ABEL: Well, I don't know about that. But it would have saved me so much time and heartbreak. Maybe the thing that would have helped me the most in some ways was the time management and talking about the artist's life. I was so totally not functional that way. I worked very slowly, mostly due to constant procrastination, and didn't get anything done. I had no community, nobody doing it around me, so I was just doing it in a vacuum.

SPURGEON: How much of you guys using the book is rolling out the book? Are you doing seminars? Do you immediately assign the books?

MADDEN: Mastering Comics is too new. We're taking a sabbatical, so it may be a while before we teach a class where we would assign it. But

Drawing Words we started assigning in most of our classes, because it's designed to be that extra resource.

At SVA, I do an ink drawing class, where I'm teaching the stuff about nibs and brushes. We do a lot of comics assignments. I have a mixture of cartooning majors and illustration majors and people in other departments. So I'm like, "Buy

Drawing Words and Writing Pictures. If you don't know how to make a comic, if you don't know how to lay out a page, if you don't know what a narrative arc structure is, read that book. Look at the

Krazy Kat and

Popeye pages." I'll have them read stuff.

In terms of the material in there, with

Drawing Words and Writing Pictures probably 85 percent of it was stuff we had already classroom tested and done a lot. Since the book came out we've tried to make a point of doing activities we've dreamed up -- sometimes we've needed activities to practice a certain principle or technique and we just made one up on the spot without having a chance to really try it. Fortunately, the ones we've tried out have worked out very well.

In

Mastering Comics it's more like 50/50. There's a lot of stuff in there where there are activities and assignments where we don't really know and we haven't had time to test.

ABEL: We've been using chapters from

Mastering Comics for years in class. We've been bringing in stuff that's in progress -- like the stuff on perspective, we've been teaching that for years. Immediately after

Drawing Words and Writing Pictures came out, we were like, "Should we assign this? That's kind of weird." [Spurgeon laughs] But we needed it, so we assigned it. I didn't want to make handouts of all this crap. That was the alternative.

SPURGEON: Have the books been received differently in other markets?

ABEL: I don't think anyone has seen it.

MADDEN: At

MoCCA we met this

Caravan Of Comics, this whole troupe of Australian cartoonists. They came to our table; they were awesome. They said they had been teaching workshops, like in Melbourne, using

DW&WP -- I had no idea it had made it that far.

There haven't been any foreign language editions out yet. There's a slow-brewing Italian edition that actually changed publishers at one point. I'm not even sure of the status on that. There's a Brazilian edition theoretically out this year.

ABEL: I think there's a different attitude about comics education in Europe, too. Once we're there, we'll be able to see better. I was in Finland last winter for a comics education seminar. People mostly haven't heard of the book but they were like, "Wow, I need that." I had only brought ten copies and they flew. I sold out really quickly.

MADDEN: This was about making comics.

ABEL: As it turns out, they do that a lot in Finland. Comics-making. Now I know.

Drawing Words and Writing Pictures was popular once they knew about it, but I don't know that word has gotten out.

SPURGEON: Do you think this book is something that people can discover on their own, or do you think of the book as something people have been eased into?

MADDEN: Like the web site you mean?

SPURGEON: Yeah. Like how much do you feel that material is necessary, how much do you feel that you have to make the case for the book? Or do you feel it's just out there now?

ABEL: The first book doesn't need that much explaining. You're going to learn the skills of making comics. Period. It's not that difficult to explain. If you sit down with the first couple of chapters, you'll get it.

The second book, conceptually, for us even, we knew what was in it and we liked what was in it, but trying to put it together -- what's the elevator pitch for this? It's tough. It's tougher to pin it down. I don't know yet whether people are going to be able to get it on their own or not.

SPURGEON: I do think it's a book people can return to. It's not like this is a "that's the week I spent on that book" kind of book. I have to imagine this is something that's going to be a companion for a lot of people for a while.

SPURGEON: I do think it's a book people can return to. It's not like this is a "that's the week I spent on that book" kind of book. I have to imagine this is something that's going to be a companion for a lot of people for a while.

MADDEN: I think of it as being a desk reference. If you're working on something and you're like, "Oh, crap. I'm stuck on this perspective problem." Or how you scan stuff the right way.

ABEL: The technical stuff, even the more structural, conceptual stuff -- for me with the writing books I've read, if I get stuck I might read somebody's book about writing scenes. It can help me get rolling again. And I hope our book does that for people as well: a tool. You sit down and read the section about composing whole books and jump in to your project again, thinking, "This is how I can solve this problem in my own book."

SPURGEON: It works as a book. It's not something where you go, "I'd like that information, but I think I'll take a class." Or "I can scrounge this stuff on-line someplace." You've made a case through the book that this needs to be a book; that this is something useful to have in that form.

There's no question. I'm just talking now.

MADDEN: We have come to realize that there is another audience for these books, that there's enough stuff in there to enlighten even a casual reader that's just into comics or learning about comics. Certainly, hardcore fans can find interesting tidbits.

ABEL: New ways of looking at things.

MADDEN: It can enrich the way you read comics. There's this more practical point of view, a more nuts-and-bolts point of view that is really compelling to readers as much as artists. I know from workshops that people are always fascinated to learn about what nibs are and what kinds of lines they make. [Spurgeon laughs] And that's part of comics, it's part of the visual language: these weird, arcane tools that a lot of us still use to do this stuff.

ABEL: I think, too, that it's not just arcane knowledge for the reader. I think it informs reading. I would really like to see more people who aren't making comics reading these books, because I think they would get a context for their reading that they don't have now. To be able to look at

Jack Kirby's work, and say, "I understand something about the process of how this was put together. He didn't ink it. Somebody else inked it. So what does that mean about the visual language here."

MADDEN: My favorite observation about Kirby, and I think this is mentioned in

Mastering Comics, is that his drawing is so incredibly dynamic that you assume he must be the origin of all these crazy page layouts with diagonals, this sort of

Image Comics look at its most extreme. But if you go back and look at most Kirby you'll see that he uses a six-panel grid more often than not. It shows you how much of that energy he was able to pack into just the panel composition across a single page, a half-page spread, a full-page spread. I'm really fascinated by that: the power that he's able to draw within the grid system.

ABEL: That may be geeky, but I think that this is one of the problems with comics literature education now. Not a lot of the teachers are equipped to talk about what the images are doing. They can talk about plot and character and all this good stuff., but are they talking about how the image composition actually tells the story? And that's what this is: that's what this art form is. To ignore that, then all you're doing is basically cheating. You're getting your students to read by giving them something that's cool-looking, but you're not really talking about the work.

MADDEN: Anecdotally we hear that pretty often from undergrads who read

Maus,

Persepolis, or

Fun Home in a college class.

ABEL: They talk about the relationship between

Art [Spiegelman] and his dad.

MADDEN: They talk about the relationships, they talk about the actual writing, but they rarely get into the visual rhetoric and the way the comics language is used.

SPURGEON: Is that because we've borrowed the language from a discipline that's more developed. Or is it that it's just hard?

MADDEN: It's hard. There's a comics literacy you need to learn and practice. A lot of people that haven't grown up with that practice don't even realize they're missing something. As much as comics are accepted now in the academy and the general public, many people are reading the stories and thinking, "This is a heartbreaking tale of the Holocaust." There's so much more there when they look at not just the drawing, but the way composition is used, the way the page turns and spreads are used, the tension between the writing and the drawing. That's all stuff that has yet to be mined in our culture. That's culture catching up to comics, not the other way around.

ABEL: I think the faculty that are teaching this stuff at the college level often are literature faculty, and they don't have training in talking about the visuals. They may even be intimidated by it.

MADDEN: It's a challenge for comics in the humanities and in education in general. Comics is great because it's so multimodal and interdisciplinary, but that also makes it a real challenge for teaching. There are very few teachers that are able to straddle the many domains comics inhabits.

ABEL: There are some. There are some great teachers who really deal with all the aspects of comics. But students, too, aren't trained to talk about this stuff. They don't have the language.

SPURGEON: I wanted to end with Chapter 15, which I liked very much as an exercise in rhetoric. It was straightforward and to the point and it had all that stuff in it that people ask first that they probably shouldn't ask until way later on. It then ends with a happy image.

SPURGEON: I wanted to end with Chapter 15, which I liked very much as an exercise in rhetoric. It was straightforward and to the point and it had all that stuff in it that people ask first that they probably shouldn't ask until way later on. It then ends with a happy image.

There are appendices that follow this last chapter, but did you put any thought into how the book would end with this last chapter. The brevity of it puts it into perspective, even. I wondered if that was intentional.

MADDEN: Now that you're saying that, I'm noticing the chapter is framed by the beginning of our character Clay looking on in fear at a giant contract in front of him. Which is scary but also implies you might get a big book-publishing contract. But it ends in a very celebratory mode, but a very modest one: a self-organized mini comicon with a bunch of people on the floor on blankets. The message there is do it because you love it, not because you expect to make money.

ABEL: It doesn't matter if you get a giant contract, go ahead and do it anyway. This is something we can offer that comes out of our background in minicomics in the '90s when there was no money in this, when you did it with friends and formed relationships through this art form. You did it because it was worth doing. There's a super-American DIY spirit: you don't need government funding to do a mini-con.

MADDEN: The book is 300 pages and we have one column of one page called "Career Paths In Comics." [Spurgeon laughs]. "You could maybe have a career in comics. Here's some ideas, but concentrate on the rest of the book first."

SPURGEON: That's what struck me, because if you do a presentation on comics, those kinds of questions dominate. So placing that chapter where you did and how you did really underline how magnificently complicated the making and reading comics can be.

ABEL: We put in a little section on copyrights, just guidelines about how you might think about it. This is one of the things that people will ask on the first day of comics class. "How do I protect my thing with copyright?"

MADDEN: "I have my webcomic and I want to make sure it's copyright-protected. I have something on my

DeviantArt site I think someone is going to steal and make a movie out of it."

ABEL: There are other priorities.

*****

*

Mastering Comics: Drawing Words & Writing Pictures Continued, Jessica Abel and Matt Madden, First Second, softcover, 336 pages, 9781596436176, May 2012, $34.99.

*

Jessica Abel

*

Matt Madden

*****

* cover to the book

* Matt Madden sketches France

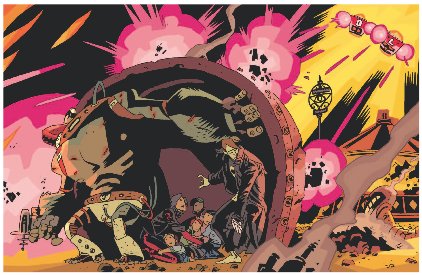

* a Blutch example from the book; there are no easy answers

* the airy design of the book on display

* digital

* page with color examples

* the Dave Stewart example discussed

* even without her book, Jessica Abel turned out all right; an illustration by the artist

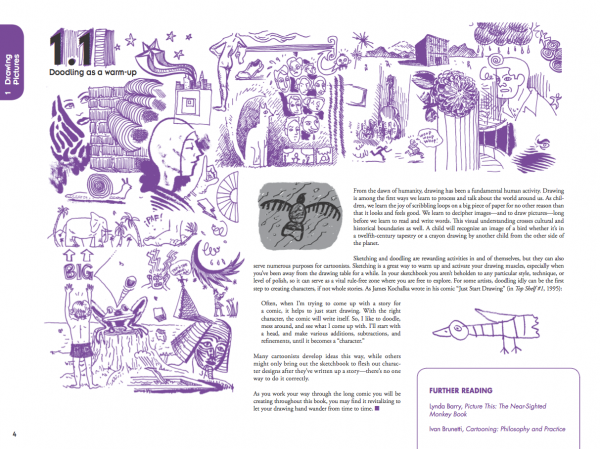

* I just sort of super like this "doodling as a warm-up" page

* facing a big contract isn't a totally bad thing

* loosely image from the book (below)

*****

*****

*****