Home > CR Interviews

Home > CR Interviews An Interview With Renee French

posted April 15, 2006

An Interview With Renee French

posted April 15, 2006

By Tom Spurgeon

By Tom Spurgeon

Renee French

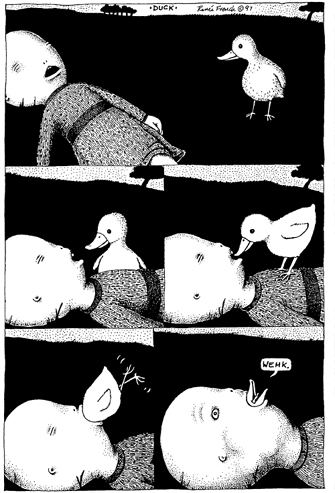

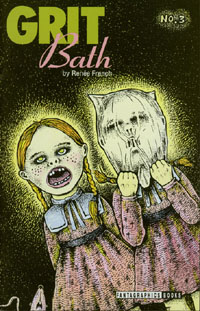

Renee French is one of my favorite people in comics. I first read her work through her solo title at Fantagraphics,

Grit Bath, in the mid-1990s.

Grit Bath remains one of the few comics to ever make me physically uncomfortable. In that title, French specialized in mixing icons of magnificent cuteness with stories of boredom and acting out, and completely horrifying moments of physical violation. Unlike many artists whose productivity collapsed after their comic book was canceled, French continued to produce at least some work year after year: some short stories at Dark Horse and Oni (the best work from this early productive phase of French's career can be found in

Marbles in Her Underpants), tons of work in multiple anthologies, some childrens' book/comics hybrids (

The Soap Lady) and some straight-out childrens' book work

under a related name. The latter two, I think, helped increase her thematic range, and certainly the visceral nature of her artwork is as effective in bringing out other extreme moments flashed through with great intensity by the younger mind and those that get caught up in their self-absorbed heat. Her latest comics work,

The Ticking, may be French's best book. It's certainly her loveliest.

I asked French a lot of questions about her process because 1) I had no idea how she worked and 2) French is very different from the perception one might have of her from her work. This interview was the result. It was conducted last year and initially ran in an issue of

The Comics Journal.

I Get Nervous

TOM SPURGEON: I've been looking at some interviews you've done. Everybody asks you bizarre questions.

RENEE FRENCH: It's true.

SPURGEON: I feel I should kick off with something like, "What is the last thing that wasn't food that you wanted to eat?"

FRENCH: "Do dogs have lips?"

SPURGEON: Is there some quality you have that makes people decide you're the person to go to for these things?

FRENCH: I guess people feel comfortable asking me the questions they always wanted -- no. I guess it's because of my work. I've always assumed it was because of my work, that somehow they feel they have to ask me weird questions.

SPURGEON: I was surprised by how many interviews you've done. Do you like that part of your profession? Do you like doing publicity?

FRENCH: No, I'm not good at it. I'm not very good at talking about my work or about me or anything. I get nervous. I don't like it much.

SPURGEON: So is it that you feel obligated? Because certainly there are artists who avoid all contact.

FRENCH: I just think it's a good idea. Since my work isn't mainstream, and since my audience tends to be really small, I just think it's a good idea to stay out there. I tend to fall off the face of the earth for a while when I'm working. I feel like I'm prolific because I'm working all the time, but I don't think I actually have a large output. The readers don't see a lot from me.

SPURGEON: Do you think there should be more work, or is there just a disconnect between how hard you work and what gets produced?

FRENCH: I think I heard Gary [Groth] say that once. [laughter] I think he put me on the list of -- oh, I don't want to get into it -- ok I think he put me on the list of female cartoonists who don't produce much. Maybe it was Kim [Thompson]. It was probably Gary.

SPURGEON: It seems to me like you've done a staggering amount of pages compared to some of your peers.

FRENCH: I really like doing anthologies. So what happens is I end up with a lot of short pieces and not a lot of long graphic novels or anything. I'm no

Craig Thompson. I like these little vignette pieces, so they're scattered all over the place. I don't feel like I need to do more work for myself, because I'm actually always working.

SPURGEON: You're just attracted to that form of expression -- those short stories, those bursts?

FRENCH: Yeah. Oh, yeah. I think I would go that way, naturally. Every once in a while I have a long story I want to tell, but it's mostly these little pieces, rather than...

The Ticking is 200 pages long. That was something that was sitting in my head for a long long time. Mostly I like little dreamy pieces better. I like reading those, too.

Maybe It's the Soap

SPURGEON: Do you like going to the studio every day?

Maybe It's the Soap

SPURGEON: Do you like going to the studio every day?

FRENCH: It's in my head -- I don't go anywhere. Sometimes I think I would like it if I had a studio somewhere else. Dave Cooper goes somewhere else and I think it really works for him. He can leave the house, and not think about home for a while. I'm just in the middle of everything. Right now there are guys in the backyard with a saw, working... it drives me crazy. At night I work in my studio and Rob works at the other end of the house in his office, and it's nice to be here. But man, I would like to get out of the house sometimes.

SPURGEON: I know you used to mull over your work during commutes or during downtime at work. It seems like a home studio doesn't allow you that dead space.

FRENCH: That's true. I get the most thinking done while I'm traveling. And we do a lot of traveling. The shower is still the best place for me. If I have a problem I'm working through, if I get in the shower, it's solved. I don't know why. Maybe it's the soap.

SPURGEON: What do you mean by "it's solved"? You see a solution for something on the page that's been bothering you?

FRENCH: Usually it's plot points. That's what gets me stuck. That's the stuff that's hard for me to work through. If I've got some character and it doesn't feel like he's doing what he should be doing, and I can't concentrate while I'm surrounded by the house, I get in the shower and I can figure it out.

SPURGEON: The reason I've started this off by asking you process questions is because looking at your work and reading you talk about it I can't tell how it gets done. I don't understand how you work from conception to publication. It seems like you have an idea you like, and then you ignore it, and then it comes to you while you're traveling, while you're commuting, or while you're in the shower.

FRENCH: Yeah.

SPURGEON: You work things out subconsciously by leaving them alone.

FRENCH: It's like astronomy. [laughter] If you're looking at some very faint object in the sky, in order to see it -- this is really corny -- in order to see it better it's best to look to the side. Right next to it. And then it comes in clear. It's something about the structure of the eye and how it works. It's really like that for me. I make notes in my notebook about, say, something that scares me. It will sit there a really long time, and then I'll have a dream or I'll be walking down the street and I'll see something that reminds me of it, and there will be a story that goes with it.

I don't think about how it happens, so it's really hard for me to pinpoint it.

SPURGEON: How much of a story do you have in mind when you start the actual physical process of drawing it, then?

FRENCH: Oh, a lot. I'm actually probably pretty tight compared to the guys in the '60s, R. Crumb and S. Clay Wilson and those guys. I don't know how they work, actually, so I should shut up about them. I write it down in words, and then I thumbnail it and then I might do tighter pencils and go from there.

Dialogue Really Bugs Me

SPURGEON: Am I to take it that when you do thumbnails, you're beating into shape something that's already essentially written? It's not a process of writing like it is for other cartoonists but a process of execution.

FRENCH: I don't know how other artists do it, but I'll go through a story in my head for months and months and then sit down and write it out longhand, and then change it a lot before I get to thumbnail stage. I think that's normal.

Things come visually first for me. Then the words come. Then the pictures come back again. I would always rather work silent. Dialogue really bugs me. I need it sometimes to tell a story, but it gets in the way; I don't like it in the panel. So in

The Ticking, there's no dialogue in the panel, the dialogue is below the box.

SPURGEON: You don't like the way dialogue looks?

FRENCH: It's like it doesn't belong. In film, unless you have subtitles you have the entire screen to work with. I feel like it mucks up the composition, unless it's part of the composition. It never ends for me.

SPURGEON: Do you think that's maybe it's because you came to comics later, this lack of natural comfort with certain effects?

FRENCH: Maybe... I didn't read them until college or after college. So yeah, maybe it would have been more deeply ingrained or something. Or I would have gotten it. I still don't really get it. I enjoy reading comics with dialogue [laughs], but I don't feel comfortable making them.

SPURGEON: It doesn't look odd to you when other people do it.

FRENCH: No, not at all.

SPURGEON: With a longer work, it seems like it would be more difficult to keep the entirety of a longer work in your head. Does it work itself out in beats, or as a series of shorter moments?

FRENCH: It's frustrating. I really like doing those little short vignettes, partly because I can keep the whole thing in my head at once. It's like a painting. But the longer stories, I start feeling a little crazy sometimes, because I want to keep the entire thing in my head and it's impossible. So I have sections, I section it off into small pieces I can think about. I still feel like I should be able to somehow turn it into A, B, C, D, E and see them all simultaneously as one big piece. That's why I could never make a movie. It would drive me insane.

Acres Of Cows

SPURGEON: Where in New Jersey did you grow up?

FRENCH: Central Jersey, I guess. Northern Central. Hunterdon County, which is sort of woods and winding roads and it's pretty. I know people don't believe that Jersey can be pretty, but it's pretty around there. [laughter] We didn't have neighbors when we first moved there. We had cows the next lot over. "Lot" isn't right, but acres and acres of cows were surrounding our property. It was about a mile to the next anything. It was country. But the City [New York] was close. It was about 45-50 minutes to the City. So it was kind of nice.

SPURGEON: Were you there your whole childhood?

FRENCH: I went to the same school from kindergarten to eighth grade in the same building. And high school in the same area.

SPURGEON: Can I ask what your parents did?

FRENCH: My dad worked for Ford Motor Company and my mom was a stay-at-home mom and then a secretary later on.

SPURGEON: You have at least one sibling.

FRENCH: I have a little sister six years younger than me, Suzy. My brother Danny is really close to my age. He's one year younger. I'm the oldest. We fought all the time, but we did everything together. He's 13 months younger. It was just the two of us when we were little. We had our own world. We had this huge backyard, so it just became our place with our scary characters that we made up, and the tree house and the rabbits.

SPURGEON: Kids that are by themselves seem to invest the house and their surrounds with story and personality. I assume that was true of you and Danny.

FRENCH: Yeah. Mr. Tree. [Spurgeon laughs] He's in the picture book I'm working on right now. The kid's book. We fed him rocks. He had a face [laughs], when I think back it was probably some kind of tumors growing on the tree that looked like a face. And then in the back, the tree was all eaten out, probably some parasite, it had a huge hole in the back. That was the stomach, and we put rocks in there. I think my dad would come in and get them out, but we thought Mr. Tree was digesting them. [laughter] I think it was my dad.

SPURGEON: Were you artistically inclined early on?

FRENCH: As long as I can remember. My mom sent me to oil painting lessons when I was five. So there was this lady that lived down the street. Mrs. Hinchman. She was a retired Swedish actress. And her beekeeper husband Mr. Hinchman. She taught oil painting. So I had private lessons with her. This is one of my favorite things about it: when I think about going to those lessons, I remember that she would give me turpentine in one cup and iced tea in the other cup, and they were the same cup. [laughter] One on one side and one on the other. They were these tumblers, these opaque tumblers. One had turpentine and one had iced tea. She would always say, "Don't drink your turps, dear." She would always say that. I would inevitably stick my paintbrush in the iced tea.

SPURGEON: Were you a good five-year-old oil painter?

FRENCH: Yeah, actually. When I look back on those things, I think, "Oh, man, I wish I could paint like that." I can't paint anymore. I'm too tight to paint now. I would really love to be able to oil paint, because I could loosen up a bit maybe. I'm really too neurotic about it. Everything has to be really tight in my drawings.

SPURGEON: I had an artist tell me that he wanted to paint later on. I asked him why he didn't paint now, and he said that all the other stuff had to go away.

FRENCH: Yeah, that's right. I know. I have this real desire to do it. But I just know I can't. I can feel it. I can tell. I have some of those paintings from when I was five, and they're really pretty good. The one that I have -- my parents have some others -- is of an Indian girl with a bright yellow band around her head.

SPURGEON: Were there other kids around? I just imagined a houseful of children in North Central Jersey making oil paintings.

FRENCH: Some of my lessons there were two other kids, one named Honey. Then my mother sent my brother along, but it didn't work out.

SPURGEON: Is your brother artistically inclined?

FRENCH: Yeah, he is. But he didn't have the right personality to sit there.

SPURGEON: It sounds like art was valued in the home.

FRENCH: My dad's an artist. He worked at Ford but he was and still is -- oh, way complicated. He's a sculptor and sort of does painting. [pause] He has an obsession with American Indians, so he would carve telephone poles into totem poles, and make a teepee in the back yard, and a headdress that went down to the ground. He had an amazing workshop upstairs with all of his stuff. He'd come home from work and disappear into that room. He was always working on something, which annoyed my mom, I think.

People Being Stabbed and Dying

SPURGEON: Is there a point in school you became "the art girl"?

People Being Stabbed and Dying

SPURGEON: Is there a point in school you became "the art girl"?

FRENCH: Yeah.

SPURGEON: Is there something different to the experience for girls that are good at art at an early age?

FRENCH: I hung out with the boys. In grammar school, I was sort of teacher's pet. And I made drawings all the time. When I was in high school, I hung out with boys. And I was always in the art room.

SPURGEON: Was it because that art was a boys' thing?

FRENCH: I never really knew girls that were into it. They'd take art and it was fun, and they would draw fun things, but the guys were more intense about it. I think that for the boys that I knew, it was their identity. That was attractive to me. I liked hanging out with them. They were really intense about it. It was a serious thing for them.

SPURGEON: Was there an age you decided what you wanted to do with your art?

FRENCH: When I was in high school, I was making really giant oil pastel drawings that were like people being stabbed and dying, holding a baby that was sort of blue. [laughs] That's when my Mom started really getting upset about my work, I think. She felt that she was doing something wrong, and that I was very unhappy.

SPURGEON: Were you unhappy?

FRENCH: No, I don't think so.

SPURGEON: Was there anything cathartic about your doing art?

FRENCH: I suppose all kids are really intrigued by death or are curious about it, but I really focused on it when I was 7, 8, 9. I focused on it but I didn't talk about it. It was an obsession. I always felt like I was right on the edge of dying. [laughs] I loved disaster movies, I would stay up late, get out of bed and come out to the living room and watch TV. I liked disaster movies and anything scary. Then I would go back to bed and be terrified. I always thought that somebody was going to break into the house and kill me. And so maybe because I didn't talk about it, when I made my drawings I made pictures of it instead.

SPURGEON: You had nightmares when you were a kid.

FRENCH: Yeah. Lots. All the time.

SPURGEON: Was it nuclear dread? You're the perfect age.

FRENCH: Yeah, I'm sure that's what it is. I'm sure that's what the root of it was. It was hanging over everyone. But I don't think I thought about it like that.

SPURGEON: The reason I ask is that otherwise, you weren't in a dangerous environment.

FRENCH: I was very safe. I think that's why my mom was surprised and worried that I was so obsessed with it, because we were in a safe neighborhood. There wasn't any crime, really. I just made it up.

SPURGEON: Did your mom's worries ever express themselves as being against your doing art?

FRENCH: No. I always had supportive people around me. My dad was absent a lot. So it was mostly my mom that was really supportive. My mom was not artistically inclined at all.

SPURGEON: Did you have good teachers?

FRENCH: I always did. The high school I went to was new, so they hired a lot of younger teachers, people right out of school. They really concentrated on their art department. We had a photography department and film classes. My teachers were great. I had positive experiences with most of them.

SPURGEON: Was it a practical knowledge or an express yourself kind of school?

FRENCH: It was both. One of my teachers, Ms. Sienkiewicz -- like Bill -- most of the kids in class couldn't stand her because she taught us composition. We had a whole term of sticking spots on a page. Most of the kids in class thought she was crazy. It wasn't important to them, but for me it was a huge thing. I really loved that class. She was so good.

SPURGEON: You were an hour from New York. Did that play a role in your development as an artist?

FRENCH: Not as much as I would have liked it to. I went there on field trips, but my parents didn't like the city and we didn't go in as a family very much. The books in my living room were my exposure. I loved Bosch, and I would sit and stare at his painting in the books that we had. We did have a lot of art books in the house, which was good, and a lot of medical and science books because my dad was into that stuff. So I spent a lot of time looking at that. Then I saw Balthus. I don't remember where that was, actually. That was sort of something big for me. Important. He's not painting landscapes, and his portraits aren't just portraits. There was something that clicked in my head that he just sort of said what he wanted on the canvas, and he didn't feel the pressure to tone it down. What I was drawing was always a little toned down, and I was getting this reaction from people that I was morbid, and what was wrong with me. What I wanted was to do my worst, and put what was really going on in my head on the paper. He seemed to be doing that.

SPURGEON: The influences were more about finding a context for your work or fellow travelers rather than people to mimic.

FRENCH: I didn't do the mimicry thing. When I was in college I met people who all they did was copy things and/or mimic someone's style. I remember being surprised by that. I hadn't been exposed to that through high school. I didn't know people did that.

Horse-Clopping Sounds

SPURGEON: Where did you go to school?

FRENCH: I went to university at this little liberal arts school, an old teacher's school called Kutztown University. I went there because one of my art teachers in high school went there and they had a great art program. A cool thing about this place is that it's a small school; it's really sort of conservative. It's surrounded by Pennsylvania Dutch country. When you first get there you're woken up by horse-clopping sounds. The horse-and-buggies around campus. It's a shock. You're in the middle of nowhere. But the art faculty is great. George Sorrels who made tiny drawings of ass cheeks and trees, gorgeous little trees, sex and landscape together in the same drawing, was sort of my mentor. His work was incredibly beautiful. My paintings always had some sex in them or something. So I was told to tone it down. Not by the faculty, who hung my work sometimes in the common areas of the art building, but by the dean of the art department. I was still told to tone it down in college.

SPURGEON: Was that disappointing?

FRENCH: Yeah! I thought that since I was going to college as an art major that it wouldn't happen. But of course I was in this really conservative atmosphere. So it made sense. If I'd gone somewhere else it probably wouldn't have been like that.

SPURGEON: How did your peers treat you?

FRENCH: I had a great friend, Erika, who I spent a lot of time with but most of the students there weren't doing anything I was interested in. You get really sick of hearing, "You're so weird." [pause] I'm sure you get that, Tom.

SPURGEON: Only because I look weird. But as you yourself have pointed out, you're very much not the cliche of someone who does your kind of work. You're presentable and personable. I could even imagine students getting behind your paintings.

SPURGEON: Only because I look weird. But as you yourself have pointed out, you're very much not the cliche of someone who does your kind of work. You're presentable and personable. I could even imagine students getting behind your paintings.

FRENCH: Oh, yeah. People liked it. They thought I was weird, but maybe not because of me, because of the work. Actually when I think about it, three-quarters of the class didn't like my work. It was bad, wrong or something. Because most of the people who went there were conservative, too. I remember most of the girls thought I was naughty or something.

One time in sculpture class out of foam rubber I made a bust of a woman with a beehive hairdo and huge breasts. The bust was cut off underneath her breasts. So she was sort of resting on these giant knockers. There were no arms. I put sequined pasties with tassels and then had a pedestal under it. [laughter] We brought our projects in and put them around. I cut sculpture class a lot because I wasn't really into it. I was into the two-dimensional stuff. I wasn't present a lot, so most of the people in the class didn't know me. So we put our projects up, and I remember this one girl walked away from it, because she was sure some guy did it and was being a pig.

SPURGEON: Were you taking advantage of the quality your art had to provoke?

FRENCH: I didn't feel like I was doing that at all. I was impatient with the reaction. They didn't get it. I just kind of felt like, "Get over it. What is the big deal?"

Quiet and Personal

SPURGEON: Now I assume by the time you were at school you had started to pursue photography.

FRENCH: [slight pause] What are you,

James Lipton?

SPURGEON: I am. I'm reading this off an index card.

FRENCH: [laughs]

SPURGEON: You've talked about photography a bit in some of your interviews, but very obliquely, in a way that suggests it's important to you.

FRENCH: It is, but it's very... private. Not private. Private's not right. It's sort of... a quiet and personal kind of thing that I don't show anybody. If somebody comes over to the house and is looking at Rob's photography, I'll show them a box of prints or something like that.

I started a long time ago. I did photography in school. I didn't feel that it went along with my drawings very much. But I suppose looking back that it did. It would make sense that it did. I did 35 millimeter when I was in school, because that was what he had the equipment for. When I got out I had sort of a series of photographic jobs. I worked for a medical photographer, I worked at a custom lab printing color photos for a criminal investigation photographer and the dental surgeon guy. Then I did actual hand re-touching of photographs. When I met my husband, rob, he was using a large format camera. 4 x 5, black and white. So I got into that, too.

It's hard to talk about it, because the work's not out there.

SPURGEON: When you talk about your artwork, you talk about piecing together some things that are inside of you, but with photography you talk about going out and finding the picture.

FRENCH: That's the bitch about photography. I find photography to be frustrating. [laughs] I really like it. It sort of releases me from the control that I have with the drawings. At the same time it demands this control, it releases me from the control, but it's frustrating to me I don't have that control. What? With the drawing I can make anything I want, and with photography it's got to be there. It's got to be something that exists. You can manipulate it, but only to a certain extent. So it's frustrating but challenging at the same time. But, it's not, "Oh, what a challenge." It's "Damn it, if I could only find what I want in this place."

I've been working with a pinhole camera for about a month. That's great because it takes away almost all of the control. You place the camera and you don't know what's in the frame exactly. You can't fidget around with it too much the way you can with a view camera. You have to wing it and I'm really enjoying that. Strangely, those are feeling more like my drawings than the large-format pictures.

SPURGEON: It seems a completely different way to approach your art.

FRENCH: It is. It's the opposite. I don't want to get into technical stuff, but the pinhole camera has an infinite depth of field. So the things in the foreground are in focus and the things in the background are in focus. But everything has a sort of softness to it. It sounds like a minor point, but when you see the pictures you can see it has a tone, a glow, it's not crisp, ... the mood feels like my drawings more, even though the technique is completely on the other end of the spectrum.

Sorry, that was boring.

This Neck Problem

SPURGEON: You become deeply immersed in your art while you're doing it.

FRENCH: It's so... it's so everything. It's really central when I'm working. [slight pause] That's not a sentence.

I liked drawing when I was a kid because it was fun and I could do it. Then, I don't know how old I was, I started drawing places. I wasn't looking to escape. I really did sort of draw a place so I could go there. To me it seems like everyone does that. You're creating these places so you can be in that place while you're drawing. Or painting. And I absolutely do that. I guess it's masturbation, really. But you're making a drawing and then you're in there. That's absolutely what it's about. Well, not completely. Part of it is about the final thing. The way I draw is so time consuming, and I get headaches from it, but the act of drawing is really comforting to me. Part of it is because I'm in that space. It's not necessarily in the place I'm drawing. It can be in the texture I'm drawing, or the feeling I'm drawing.

That probably sounds completely pretentious, but it's true.

SPURGEON: Now due to the nature of what you draw, are there consequences in terms of moods and feelings?

FRENCH: I'm in a bad mood a lot, actually. If I'm drawing something sad, I'm sad. For sure. But I don't see how you can separate yourself from that, really. When you're making something, drawing some sad situation, I can't see how you can be sitting there with a happy face on. I think that the creepy stuff, I really do end up feeling creeped out while I'm working on it. That just seems really obvious. How could you not?

SPURGEON: Yet you have these stories worked out in your head.

FRENCH: Yeah, but...

SPURGEON: Does the emotion come from a sense of revisiting it?

FRENCH: When it's in thumbnail form and the story's worked out, that's just the skeleton. When I'm drawing I'm fleshing it out so it becomes a real thing. When it's penciled, line drawings can have real volume to them, but I don't feel like my work has volume until it's colored in with all of the tones and everything.

SPURGEON: Does the intensity of the experience ever make it difficult to work on something?

FRENCH: It did with

The Ticking. Yeah. Normally it doesn't, because it's really where I want to be. Even though some of the stuff is intense and gross. I like being there. With

The Ticking, the story started making sense to me that it was something personal about me and my dad, so I would walk around the chair and not sit down for a while because I didn't want to go back into it.

SPURGEON: And you said earlier there are hangovers.

FRENCH: I get a headache because of the way I hold my body while I draw. I've worked on that for years and years trying to change it. I've drawn in the same position all of my life and developed this neck problem and stuff from drawing. [laughs]

SPURGEON: They've been training you since you were five. [laughter] You'd think you'd have the perfect form.

FRENCH: Yeah, you'd think.

SPURGEON: There is a physical cost to cartooning, even though people tend not to talk about it.

FRENCH: In the early '90s, Julie Doucet and I wrote back and forth a lot on paper. I remember getting a letter from her one time saying she had to stop, that she was late getting her book in, because her back was really hurting and that she was on bed rest for a little while. It sounded really serious. I can't remember what it was exactly that was wrong, but I remember she couldn't draw because of it. I hope I'm not getting the details of that wrong.

That scared me a little bit, because I always had this pain in my shoulder whenever I drew for a long time. I would draw for hours and hours and get up and have this pain in my shoulder from turning my head. When you're drawing, you're kind of in that moment, you're in this space where you forget what time it is and you don't realize how much time has gone by until something startles you and you look at the clock. So during that time, when I draw, I get really sort of kinked. I twist my neck around -- that makes it sound like I'm Linda Blair or something [laughter] -- but I sit in a really bad position. A couple of years ago because I was getting so many headaches I went to a physical therapist and he gave me a different way of sitting to draw. And it helped for a while, but now I'm developing bad habits again. I actually sit upright with a drawing board on my lap. I don't work at the table, because at a table I do that bad thing. I sit up in a chair with a drawing board and a pillow under my arm. And that's how I draw.

Hands are Hard

SPURGEON: Do you ever come up with something you let go of because it's not suited to you as an artist? Do you abandon ideas?

FRENCH: Yeah, I do. A lot. Four out of five.

SPURGEON: For what reason?

FRENCH: It seems like a good idea at the time, and then I don't care anymore. It's just not interesting anymore.

SPURGEON: Does what you come up with always match your artistic range?

FRENCH: Oh. I see. I was talking to

Chris Ware one time and he said, "I don't do stories with cars in them because I can't draw cars." He's full of it, but I guess that's true. But you know what? I don't think about that while I'm writing. Sometimes I'll put somebody's hands in their pockets because hands are hard. I hate drawing hands and yet I'm constantly drawing hands. [laughter] I have so many shots of hands doing things.

SPURGEON: You're so mean to yourself.

FRENCH: I suck at drawing hands. And then I have an idea where I'm POV person building a tiny ladder. So I have to draw the hands. All the hands are mine, of course. They're lame, but I do them.

SPURGEON: Are there other artists where you look at their stuff and think, "That's an interesting range of effect," and you become envious of them?

FRENCH: Yeah, a lot. [pause]

SPURGEON: You can name names.

FRENCH: [laughs]

SPURGEON: There's a difference between admiring an artist and coveting their skills.

FRENCH: Jeffrey Brown. Because I would really, really like to be able to capture something with a few lines and have the gesture be exactly right and have this sort of pure feeling about it like that. My stuff is so noodly; I wish I could be loose sometimes. And his stuff is loose and yet you get the sense of him. I love every panel of his stuff. I'm sort of in love with his work and the honesty of it. It's so straightforward. I don't feel like I can do that.

Anders Nilsen, also, is sort of like that. There's something very pure about the birds stuff that I wish I could do. I wish I could let go a little bit and do that kind of thing. When you read Anders' stuff you get this light feeling. And his writing is so good. And Peter Blegvad -- his range, I love the fact that he's not afraid to do everything. And Ivan [Brunetti], too, he's so good at everything. He's a genius.

I love Dave Cooper's work, but I feel closer to it. He's a better drawer than I am, but underneath there's something similar in the wiring of it. So I don't have that feeling -- except sometimes I wish I could draw flesh in clothing the way he draws it. But mostly I feel close to it.

I Love Animals Very Much

SPURGEON: Did you read much when you were a kid?

I Love Animals Very Much

SPURGEON: Did you read much when you were a kid?

FRENCH: One book I read over and over was

Of Mice and Men.

SPURGEON: There's a horrible feeling of inevitability in that book.

FRENCH: I think the thing that really got me, what interested me the most was the big retarded main character, Lenny. He's really strong and kills these animals without meaning to by loving them. He's petting the dog so hard he kills it. He has a mouse in his pocket that he carries around stroking it and he kills it because he's stroking it so hard. It's a really simple idea, but I read that over and over again because that rang true to me somehow. I'm not sure exactly why.

It might be because of that time I crushed the cat's head by accident when I was a kid.

SPURGEON: Someone wanted me to ask you: "Did she have pets growing up, and are they all right?"

FRENCH: I did have a lot of pets. I love animals very much. You can ask anybody who knows me well. I'm allergic to most of them, also. The cat story is, my cat, one of our cats, Bosley, had kittens. We named all the kittens. We were going to give them away, but we named them all. I was sitting on the couch, I don't know how old I was, probably drawing, not paying attention. I had socks on. The kittens were all over the place. This one kitten was under the couch and he had fallen asleep with his head under my heel. His name was Oscar. I was sort of sitting there and then I got up. When I got up, my heel came down on his head and I heard this crunching noise. I stepped on him. I felt like I was going to throw up and ran into my room and was crying. I was convinced I'd killed this thing. My mom brought it into me, and there was this stream of blood coming down from his nose. She said, "Look, he's okay." He was really retarded after that. He might have been retarded before that. To me he died. I killed him by accident. That was the only time I did anything like that. I was always bringing birds home and then infesting the house with lice. And I had a lot of bunnies.

There's the story of Bill the Bunny. I know I've told that story before. Bill the Bunny lived in a hutch my dad built. He got sick. One day I went out there, I was going "Bill, Bill." He fell to his side, and he had maggots eating his stomach. And he was still alive.

SPURGEON: [moans]

FRENCH: He died shortly after that. That was Bill. He was way cool.

Now I'm so sad.

SPURGEON: How did we get here?

FRENCH: It's your fault.

SPURGEON: We got there from Of Mice and Men

. Did writing ever hold any interest?

FRENCH: I'm not verbal. I'm not good with words, obviously. I'm much better with pictures. I talk a lot, but I'm not good with words. I don't feel comfortable writing prose because I'm not good and there are a lot of people around me who are. I have an inferiority complex.

I Think It Feels Jerky

SPURGEON: Was there something about your art you had to change to make it work for comics? What were your first experiments like?

FRENCH: They were awful. My first stories I worked with a writer. My then-husband who was a writer. I was drawing his stories and I did my own little stories on the side when I was at work. They were one-pagers. So I could feel they were one piece. "Cindy" -- I don't know if you know that one -- the one where she staple guns her eyes? That was just sort of one little idea I thought of in the ladies room stall. I kind of learned by doing little pieces, one little thing at a time. The stuff I did with Dan, the first ones were such a struggle to figure out. The main thing was I had to figure out this character where each time it had to be the same character. That's something I never had to do before. That was just so difficult. I could have simplified them and given them broad characteristics, but instead I was drawing realistic faces back then. That was a major thing. Pacing was another thing I thought impossible to figure out.

SPURGEON: Were you looking at other comics very closely?

FRENCH: If I had been smarter, maybe I would have done that. I never sat down with a comic book and said, "What is he doing here?" Instead I stumbled through my own stuff trying to make it work. The early stuff is really awkward timing-wise. I think it feels jerky. The pacing is really uneven and not right, I think.

SPURGEON: Is there a comic you can point to where you think you finally got it together, even roughly?

FRENCH: Corny's Fetish, maybe. I think that story worked as a story, and the pacing is consistent. In

The Ninth Gland the pacing was inconsistent.

SPURGEON: What was hanging you up with the pacing?

FRENCH: I was getting a little bit

David Mamet-y in the stuff I was doing. You know how he repeats dialogue over and over again? Sometimes it feels really slow. You get to a certain scene and it just slows down. You think, "Why didn't he have her say it once instead of twelve times." I couldn't tell when I'd said it. It's still really hard. When you're making the thing, you know what you're trying to say. It's hard to know what the reader will get. I think in a lot of my earlier stuff I was over-telling and not trusting the reader to get something. Or maybe I was trusting the reader too much and nobody knows what the hell it's about at all.

SPURGEON: For an artist who gets an effect from her art -- not pared down, not symbolic, but from the quality of the drawing -- I would imagine that learning to economize in other ways so that your work reads well would be very difficult.

FRENCH: It is very hard. I don't think I've got it. In the new one, I'm not sure if anyone is going to get anything. [laughs] I have this fear that people are going to read it and just say, "What?" Not understand what happened. I think there's enough there that the story is told. So it's not really that. It's less linear than a lot of stuff I've done but not as far away as the really dreamy ones.

SPURGEON: You mentioned once in passing that you wanted a bigger audience, and that you thought you could get this bigger audience through comics. That doesn't seem in line with the specifics of your artistic impulse, which is extremely personal.

FRENCH: I think I wanted to escape my situation at the time. I think it was more about getting out of my life, then. I was in a really bad place and I wanted to get out of there and having a wider audience sort of represented that to me. I felt that I would be communicating with people who weren't right around me. But, yeah, you're right, I don't think about the audience when I'm working. I know that I do to a certain extent, but I don't like to. And sometimes, some of the earlier stuff I actually felt guilty it went out there. Not now as much, and not when it first came out. But in the middle I felt guilty that people had to look at that stuff.

SPURGEON: It was too self-indulgent?

FRENCH: Why would anyone care about that stuff? I was in a bad place, it was personal, and I couldn't understand why anyone would see value in it.

SPURGEON: You still feel that way.

FRENCH: A little bit.

Your Heart is Dead

SPURGEON: You have a very specific style. Have you ever wanted to break off in some radical new direction? Does your approach encompass all you want to say with art?

FRENCH: Yeah. Well... no. There are other things I want to say. I'm not done. I think what you're saying is the range of things I want to say seems to be narrow.

SPURGEON: Can you do anything you want within your style? Has there ever been anything you wanted to do where you've said, "That's just not me."

FRENCH: I have had ideas tossed to me by other people where I've thought, "I'm not interested in that." Where I'm not interested in dealing with that issue. I don't think about my work in terms of issues. I don't know if anyone does. Maybe that's just queer to say. I don't think, "Here's a problem. Here's an issue. I'll write about this." I know that my work is more internal, and that's why a lot of times I think nobody would be interested in it.

I remember

Dean Haspiel talking about responding to other people's work one time at

SPX or

ICAF during a panel discussion. He was talking about some other cartoonist doing something and then he responded to that other cartoonist's work by making a comic. That to me was so Martian. I didn't understand why you would do that. I said something like, "I never thought about it like that." And he said, "That's because your heart is dead." [laughter] I can't remember what he said. It's in a transcript somewhere. "It's because you have a black heart." Or something like that.

SPURGEON: Have you figured it out since?

FRENCH: It just never occurs to me. It's not that I don't care what other people are doing. That's not what it is. I read other people's work and I enjoy it. It's sort of like why would I... I don't know!

SPURGEON: For many artists, they encounter a piece of art or a process that changes everything. You don't have anything like that. There's not that moment of radical change, that thing that caused you to see everything differently. So while most artists don't respond to every other artist they meet, there's usually one or two -- and you don't even have that.

FRENCH: I didn't think anybody did. Then I started reading interviews and talking to artists over the years. And it sounds like most people do. And I think, "What's wrong with me?" I also feel sort of selfish, like I'm inside my head and not paying attention enough. But I do look at artwork all the time. It's not like I don't look at it and idolize people's work, but I feel like I'm stealing. If I see somebody's work and I think, "Oh, man. That aspect of that person's work is amazing. It really moves me. Maybe I'll use some of that in my own work," that would feel like I was stealing. That's not what I'm saying, that's not my work, it's somebody else's.

SPURGEON: But you have talked about influences.

FRENCH: Sure.

SPURGEON: What is an influence for you, then? What does that word mean?

FRENCH: Well... like

David Lynch. Not to be too cliche or anything. David Lynch when I was in college. When I saw

Eraserhead I fell in love with it and thought, "You can say what you want." You don't have to follow some rule. You can say what you want the way you want it. Which seems obvious, but it wasn't to me at the time I saw that movie. It was a lot like seeing Balthus for the first time. With Lynch's stuff I always felt a deep comfort in seeing his work. It makes me feel that not only can you feel those things that he's feeling you can express them, and that's okay. I think before I saw his work I thought , if you have those kinds of feelings you should keep them to yourself. Even though I was drawing stuff that was disturbing my mom. In high school I still sort of felt like you wouldn't want to put it out there, really. For me, he's an influence because he showed that you can portray what you're feeling in work and it's okay, even if nobody's going to get it.

SPURGEON: So an influence is someone who is inspirational rather than someone whose technique you pick up on.

FRENCH: I think the thing with technique is that it feels like swiping from people. That scares me. I love Dave Cooper, and I'm always really aware, if I draw a line that seems sort of similar to his lines, I get afraid and pull back. I'm aware it might be a little bit like his lines. I'm incredibly aware of that stuff.

SPURGEON: Is it the lack of authenticity that bothers you, or being called out as a copier?

FRENCH: It's not about being called out. I don't want my work to be derivative, because I feel like what's the point of doing it if you're saying something somebody else has already said, or doing it in a way someone has already done it. It already exists; why should I do that? With Dave, I really relate to his work a lot, so I see a lot of danger there. I keep his books around almost so I don't do what he's doing. Just to make sure I'm not.

SPURGEON: Are there any others you relate to in that way?

FRENCH: No. [laughter] No, because I don't think I'm... no, I don't think so. There aren't any people I'm that close to.

SPURGEON: Because he's so close, that's the danger.

FRENCH: The story

The Ticking, I wrote it years ago. In the story there was this floating fair/circus that had freaks and animals and stuff. It would float from port to port. It was all written out in the script. Then a few months later, I guess at San Diego, I saw

Ted Stearn there. I bought his

Fuzz and Pluck, and there was a floating circus in his story. I was like, "Oh, fuck!" You know? [laughter]

I thought of the circus in bed one night; before I fell asleep I thought of a floating circus. It would be really cool with the lights reflecting off the water. I was psyched about this image. And there it was in

Fuzz and Pluck. I had to take it out of my book. Later I was on a panel with Ted and [David] Sandlin and Jonathan Rosen. I told Ted about it. He was like, "You could have used it. What's the big deal?" I had to take it out of the story. There's no way I could leave it in. It was already done. I was kind of glad that he'd done it far enough in advance that I saw it. That it didn't come out at the same time.

SPURGEON: How would you react if it had come out at the same time?

FRENCH: I'd be worried that he thought I'd copied it somehow. Not other people. I'd mostly be worried that Ted would feel that I'd found out that he had this thing and I'd used it. I would feel bad about that. He had this really cool idea and I took it and used it and didn't do it as well. And then I would also feel really crappy myself. Oh great, what's the point?

SPURGEON: Have you ever seen yourself in other cartoonists' work?

FRENCH: Yeah.

SPURGEON: How do you react to that?

FRENCH: I think it's cool on one level. I think it's really cool. I don't think it comes from looking at my work; I think these people just sort of think like me a little bit, I guess. I'm not going to remember his name... the guy who does

Chrome Fetus?

SPURGEON: Hans Rickheit?

FRENCH: His work, when I saw it for the first time I really responded to it. And then it really started feeling like my earlier work to me. Better drawn than my early work, but it felt like that stuff. Like the Kirsten Twins in particular. It's very possible he had never seen my stuff and it's just sort of like that because that's the way he is. I kind of like that. I think it's fun to see that.

SPURGEON: Do you ever turn down commercial work? Can you even do a lot of commercial work given your process?

FRENCH: I don't get a lot of offers, because I... well, I don't know why. [laughter]

Entertainment Weekly doesn't look at my work and say, "It'd be great to see a drawing of Tom Cruise by her."

SPURGEON: Let's say they did -- could you even do that?

FRENCH: If they would let me... see, if somebody comes to me, I assume they know my work and they would give me some leeway. I used to do illustrations for the op-ed and letters page in the

New York Times. That was really fun that. I loved that. I had to turn it around in a few hours and get it out. I was working with Peter Buchanan-Smith, and he was great. So yeah, sometimes. But I'm not really that into doing that kind of thing. I don't feel... nyeh. I think it's only fun because of the fast turnaround time. I can't stand turning something in and having somebody say, "Well, it's not exactly..." But nobody likes that.

You Devil Woman

SPURGEON:

SPURGEON: Grit Bath

. Do you look back on that experience positively?

FRENCH: Yes. I love

Gary Groth. He gave me the shot.

SPURGEON: Do you remember how that offer was made? They were doing a lot of comics at the time, this second wave of comics.

FRENCH: I did a piece in

Real Stuff with Denny Eichhorn. Denny wanted me to do this story; it was like 11 pages long. And Gary sent me a letter saying that he really liked the piece and he would like to see some of my work that I had written myself. I hadn't written that much myself except those few little pieces. So I sent him a Christmas card with a couple of samples in there so he could see the kind of things I was writing. Not long after that I got a phone call from him. He said, "Would you like to have your own one-shot," I think he said. "Put a bunch of stories together and we'll publish a one-shot." Then it turned into a three-issue thing. And then I was part of that group of people that were told that we weren't going to continue the series we would do graphic novels now.

The Ticking was a victim of whatever happened there.

SPURGEON: Was it enjoyable to have that kind of showcase, however briefly?

FRENCH: It was really exciting for me, because I could pretty much do whatever I wanted. I didn't have to worry about someone telling me, "No, that's too offensive." Or "That's not the kind of thing we're looking for." He gave me free rein pretty much. It was great. I loved doing it. The first issue had the fistophobia story in it. I got the most mail about that of anything, I think. That story was mainly why it was seized at the English and Canadian borders. The second and third issue, which I thought were pretty tame, people were still being shocked. I remember getting a box of my comics and I was working an office job. I remember the box coming to my work address. One of my friends there was like, "Let's open it." And my boss was standing around, "What is that? What do you have there?" Nothing! And started putting it under my desk. I kind of wanted to take it out and say this is my comic book and hand it around to people. But I was terrified my boss would read it. [Spurgeon laughs] I was terrified. I had these friends that were like, "Oh, come on." I would grab their shirts white-knuckled, "Listen to what I'm telling you. Do not show this to them."

SPURGEON: To be honest, I had to prop those comics on the dashboard of my car and read them from the back seat. [French laughs] And that was last week.

FRENCH: I never knew how anyone would react. I was single then, and I used to go next door and get food at this Japanese restaurant. There was this guy there, this Japanese guy and he was cute. We would talk whenever I'd go over there. My friend Vikki said loud enough for him to hear, "Renee does comics," and he said, "Oh, you do comics. I'd like to see them." I thought, "I don't know." I'm thinking, "He's Japanese, I've seen some of the Japanese pornography [laughter] maybe he's kind of open-minded." So what I did was I got the least offensive one, which was #3, at that point. Issue #3 had just come out and I looked through it and I remember thinking, "There's not much that's offensive in here." I brought it over the next day in a manila envelope and gave it to him.

I got this message from him on my voice mail at work, basically saying, "You evil woman, you devil woman. Why did you give this to me? You've cursed my family." [laughter] He was way offended. So, so offended. So after that I would warn people and I still do.

SPURGE