Home > CR Interviews

Home > CR Interviews A Short Interview With Gerry Alanguilan

posted October 14, 2006

A Short Interview With Gerry Alanguilan

posted October 14, 2006

If you spend enough times learning about comics, one thing eventually becomes clear. The more knowledge you gain, the more knowledge, it seems, there is to gain. Filipino cartoonist

Gerry Alanguilan has a passion for the great comics tradition of the Philippines: its values are embodied in his work, its artists trip off his tongue, provide the working material for articles he writes, and their art makes its way to his Komikero.com site; its lost magazines and developing industries and invasions into other countries and young artists working together cross the fabric of his life; it's a complete world of comics unto itself, and Alanguilan is its most enthusiastic guide.

I could sit down with Alanguilan on any day of any year and throw questions at him about the shape and scale of the Filipino contribution to world comics until one or both of us fell asleep on the keyboard. Two reasons I thought it would be nice to sit down and do a short interview with him now: next week marks the

2nd Philippine Komiks Convention, which he managed to bring up first; and this Fall should see the publication of the second issues of his comic

Elmer.

Elmer is the kind of comic that North Americans used to see a lot of in the early 1980s: a story about life using a fantasy element -- in this case sentient chickens -- and executed with every bit of craft Alanguilan can muster. I'm not sure a story about a family of chickens is for everybody, which is one of the reasons I like it. When Alanguilan talks about putting together a comic book, there's a real passion a thousand universes removed from scoring a movie deal or using the current project as a stepping stone for the next or even playing the part of a market corrective. I've missed the frequency with which one used to encounter comics for comics' sake.

The following was done by e-mail, with some slight copy editing by me. Thanks to Gerry for a quick turnaround and supplying extra art.

Please visit

the Elmer site, the cartoonist's

personal site and

The Philippines Comics Art Museum. If you're a retailer and would like to carry copies of

Elmer, I'm sure he'd love to hear from you.

*****

TOM SPURGEON: What got this book from the idea stage to finally getting out in paper form? You've written about your passion for getting this out there, but I was wondering what aspect of it appeals to you specifically -- is it the story, the chance to write and draw something, the chance to explore a certain kind of illustrating...?

GERRY ALANGUILAN: The illustration aspect of it was secondary, to be honest. All I was really concerned about was to be able to draw this really well. I felt I missed a great opportunity with an earlier work,

Wasted, which was well received but was crippled by very bad art, at least in my opinion. I resolved not to have that problem this time around. Although I was taking much greater care with the art, it is the story that I really wanted to explore. But that idea took a long time coming.

Wasted had been finished for many years now, and had gone through many printings. People have been asking me what my next "serious" project will be. I had been doing these photocopied mini-comics things called

Crest Hut Butt Shop, which I believe was

reviewed at this site at some point. I've been doing all that of course, whenever I can get a break from my bread and butter inking job for

Marvel,

DC, and

Image. I had been pointing to

Crest Hut as something I actually take seriously, regardless of its subject matter and manner of execution. People would say, "No, really, what's your

next serious project?"

I have this great black blank book where I write down all my ideas as they come to me. Some of those ideas are crap, but some of them seem interesting enough to explore. But none of them jumped at me more than this idea of talking chickens. What if chickens were intelligent and could talk? What would they say to us? They'd be mighty pissed at us, I would imagine. We've been eating them all throughout history. That picture of a really pissed chicken freaking out at some mistreatment really sparked something in my head. It was an opportunity to tell a story that isn't really about chickens, but of humanity in general, and how we treat each other. Once that concept fully formed in my head, additional ideas have never stopped coming. It's like I opened a tap somewhere and all this is coming out so fast that I have to carry around my black book around all the time. I can never tell when a single stray idea would suddenly evolve into a full blown scene.

SPURGEON: Is there a reason why this is a full-blooded paper comic book rather than an on-line project? Had you thought about doing this on-line, given your considerable virtual presence?

ALANGUILAN:

ALANGUILAN: I'm a traditionalist at heart, who is struggling to survive in a suddenly digital world. I was already fully grown and conscious when we still wrote letters on paper almost exclusively. I still remember a world without cellphones, without home computers and the Internet. I used to write three letters on paper every single week and I really enjoyed it. I loved doing it.

Ever since I came online in 1997, that part of me literally died and I still grieve over it. But what can I do? This new virtual reality world is part of the future and I better get on it or get left behind. In many ways it's become true. If you are an aspiring artist who wants to work in comics, it's a serious disadvantage if you don't know how to use the computer.

After using computers and being online for almost 10 years, I feel I've finally found that balance between the traditional and the digital. The traditionalist in me would beat the crap out of me if I ever drew on the computer using a tablet, but it allows me to scan my work and color it in the computer. The real bottom line that the traditionalist in me is demanding that when I do my own comics, meaning those I write and draw myself, they will always be in print. Everything else can be digitized.

There is very little that can match the thrill of an actual comic book I created existing in the real world, something tangible right in my hands as I turn the pages. A huge part of the thrill comes from me being a lifelong fan and collector of comics. I had this huge stack of Marvels and DCs when I was a kid. I would read them whenever I had the chance, specially if it was raining and I couldn't go out. Those moments were magical. This kind of sentimentality wouldn't make sense to someone who didn't have a childhood like that of course, and it would be quite conceivable that some young kid today would find himself similarly waxing nostalgic about some cool and awesome webcomic he read online back in 2006.

In the spirit of not knocking it till I tried it, I did take tentative steps into the webcomic world many years ago. In fact, one of them is still online

here.

I got positive feedback from it, including one from

Scott McCloud no less. So that was quite a thrill.

It's a tantalizing new universe out there of really amazing webcomics. I've been browsing some of them and some of them are incredibly well done. But the experience of doing something online doesn't thrill me as much as doing something in print.

You know, if the whole print comics world comes crashing down and everybody came online, I'd most likely still be doing print comics. But I will still be online talking about it and making video blogs about it. That is probably why I chose to make use of the Internet a lot, and that is to bring attention to the work I do in print.

If one day using paper would become illegal for the sake of the environment, I'd most likely stop doing comics altogether. It's that important to me.

SPURGEON: The first issue of Elmer

sets the stage and kind of sketches out the world -- did anything change about the story once you finally began to produce pages? Has the story surprised you at all?

ALANGUILAN:

ALANGUILAN: I planned the series as four issues. The first issue would introduce the reader to the world and the characters. I got some feedback from the first issue saying how ridiculous they thought the idea was at first, but they thought it completely plausible after reading it. Some people even forgot they were reading about chickens. I think that's great because it sets them up to be more receptive to what happens next.

Issues #2 and #3 will both be double-sized and they will tell the story of how this world came to be. By the end of the third issue, we will be back to the time set in the first issue, where chickens are already part of the everyday fabric of society. Issue #4 will be a kind of epilogue to the entire thing.

That is pretty much the structure of the story, and I don't see myself deviating too much from it. Those are immovable parameters I have set for myself. I've had to do it so I can have a framework in which to work. I can't afford not to have it because I'm always afraid of getting carried away and lose sight of the story I really want to tell. It also helps me to be more disciplined and makes me capable of actually finishing the project.

Within those parameters however, anything can still happen. I had always planned a bloody scene in the second issue, but when I was writing it, I went to places I never expected.

SPURGEON: Why a chicken? Do you have direct hands-on experiences with the animal when you were a kid or anything like that? Is there anything about the role the chicken plays in your culture as opposed to that of the US that might inform your work or is a chicken a chicken everywhere?

ALANGUILAN: I live in the province here in the Philippines, which would be something like living "in the country" in the US. I'm always surrounded by chickens. I hear them crowing all the time. There's a large family of chickens who live nearby and everyday they would pass outside my window and I would watch them, trying to figure out their family structure. In fact, I pretty much based some of the major characters on these chickens. There's this alpha male that I've come to call "Elmer" and a hen with a fluffy cap on her head I've come to call "Helen."

I like observing chickens. I find their jerky movements and seemingly paranoid eyes amusing. I find that the indignant sounds that they make when they're surprised or disturbed to be hilarious. It's one of the sources of the characterization of my characters, specially Jake.

When I was younger I had this pet rooster I named Solano. Immaturity and not knowing better come with being young, and I've since realized that I really hadn't treated Solano as well as I should have. I always belittled his masculinity by surprising and disturbing him in the middle of a particularly manly crow. I always made fun of him by surprising him every so often just to be amused by his indignant clucking.

A few weeks before he died he actually ran up to me and attacked me, trying to poke my eye out. The incident really shook me and made me grow up a little bit. It's one of those things that you don't forget and informs your life into old age.

SPURGEON: I like the sibling interrelationships that you've worked out. What is it about sibling to sibling relationships that interests you enough to have included them as a big part of this work?

ALANGUILAN: It's one of the devices I used to flesh out this world. I wanted to describe to the reader what this world is like and I thought doing it while introducing the brothers and sister would work. I had major concerns about that scene because I thought it might bore people out of their skulls, seeing that it goes on for several pages with just chickens talking. And yet it's an important scene in that I establish the norms of morality that these chickens and the humans live by. In many ways, it sets up the reader for what would be happening in subsequent issues.

SPURGEON: Your chickens are very handsomely drawn.

ALANGUILAN:: Thank you!

SPURGEON: How much of a process of character development was there, and is it different to do that with animals?

ALANGUILAN: Figuring out the right way to approach drawing the chickens took some time. I had begun drawing the story early in 2005 or thereabouts. But there was something about the first page that seemed forced. I didn't feel comfortable about how I was doing things. Perhaps I was doing it too realistically. I let it lie for almost a year, concentrating almost exclusively on inking. I began drawing it again in late 2005. I've come to realize that drawing the chickens too realistically would rob them of an expressiveness I desperately wanted them to convey. A certain amount of cartooning was required, but not too much that would make them look goofy and unbelievable. I've had to make the eyes do things that they normally won't so I can give them the proper expressions I wanted them to have in any given scene.

I tried very hard to establish different characteristics for each chicken, not only in terms of behavior, but also in terms of the art.

May is clean and conservative and upholds traditional family values. She believes in the sanctity of marriage between a man and a woman (Never mind if one of them is a chicken, and the other is human.). She's very formal in her manner of speaking, but formal in a somewhat forced manner. I might have gone too far by not allowing her to have any contractions, but I wanted her to really sound different from the others in a strange and formal way.

Freddie/Francis is well groomed and a really nice guy. Here I wanted to show what a really good looking chicken is like in their world. He may well be considered as a "metrosexual" chicken. There is speculation that he may be gay, something that drives the traditional May up the wall.

I approached the other characters, specially Jake and Elmer, in a similar way.

SPURGEON: Is there anything we can metaphorically read into your use of animals in Elmer

in a metaphorical

sense? Animals in comics have been used in a variety of ways: as physical exaggerations, as paragons of difference or as embodiments of alienation. Is there a secondary meaning we can get out of your use of chickens?

ALANGUILAN:

ALANGUILAN: The primary intent was to completely flesh out the idea of chickens suddenly gaining intelligence and human consciousness through the experience of one family of chickens. In the reality of this story, the chickens truly are chickens and the humans are now forced to deal with that fact, and to deal with how they have treated chickens in the past. In so doing, I've created a new "minority." A new race that people would now have to contend with. I thought I would take a completely ridiculous premise and treat it as seriously as possible. It has the potential to be fantasy or science fiction, but I tried very hard to steer clear from any indications of such. I really wanted to come up with a straight drama.

Some humor can be derived from the fact that they're chickens, and in a way that works for me because I can possibly bring in issues that people would not have otherwise been receptive to had I decided to use real people instead.

Out of this evolved a secondary intent, and that is to use this new "minority" as a means to offer personal thoughts on race, hatred and prejudice. By using animals, and specifically chickens -- animals I find funnier than most -- I could soften the blows of some really hard issues.

SPURGEON: I'm interested in how you keep a certain tone to the work. Given that you're using some classic cartooning effects and not using others, are there any that you've wanted to use but then decided not to because they were too cartoony?

ALANGUILAN: I've taken quite a bit of effort not to make the art too realistic but I've also had to take equal effort not to make it look cartoony. If there's anything I can say to describe how I approached doing

Elmer, it would be to say that I've tried very hard to keep things "moderate." I have a tendency to go to extremes and exaggerate both ways.

My past work seem to bear this out. My

TIMAWA was an exercise in back breaking research and meticulous detail...

... while

Crest Hut Butt Shop was a drunken exercise in "Wala Lang."

"Wala Lang" is a common Filipino expression that means "I just felt like it because I have nothing else to do and/or I'm bored."

Crest Hut was something I did very quickly, written, drawn and lettered as I went along.

I wanted to find a balance between those two things. I tried to avoid realism too much because people would probably take it

too seriously, and besides it would take forever to finish drawing. I tried to completely avoid doing it too cartoony, accomplished quickly and haphazardly, because I wanted readers to take this somewhat seriously. In fact, those who know me through

Crest Hut thought it was just another one of those, but they quickly realized it wasn't. Those who were expecting something serious who were disappointed I decided to do chickens, quickly realized I wasn't kidding around.

SPURGEON: You use a lot of shifting perspectives in the first issue of Elmer

. Was that a particular challenge, to depict the world from a human being's point of view and also the point of view of these chickens? Those switches becomes sharper as the issue goes on.

ALANGUILAN: It was an intentional deception on my part to make the reader go on thinking that it was a human that was talking in the first few pages of the first issue. I thought it would make the eventual revelation much more disconcerting.

But I actually debated with myself about putting it in because I thought it was a gimmick. Tricking the reader into thinking one thing and revealing it not be the case is something used so often before that I felt it might cheapen the story I wanted to tell. I chipped away at a lot of things in

Elmer, mostly things that I thought would over sensationalize or over dramatize things. The first draft was vastly different from what eventually came out.

Issue #2 will have a lot of shifting perspectives from Jake, to Elmer, to Farmer Ben. It's very interesting to do these different perspectives because I get to tell the story through the eyes of different characters, and see how each point of view affects how the story is told. I'm a big fan of Japanese movies and [director

Akira] Kurosawa's

Rashomon is one of those I'm very fascinated with, along with

The Lower Depths (a personal favorite) and

Ikiru.

Frank Miller and

David Mazzucchelli's

Daredevil: Born Again is another thing I take great inspiration in. The shifting perspectives on that book are incredible. In one page alone I can count at least four different perspectives from four different people, and yet you don't lose track of the story being told.

The shifting perspectives allow me to approach the page differently in terms of storytelling and illustration. Enclosed is a page from #2 with perspectives from both Jake and Elmer. Jake is reading from Elmer's book. Jake has difficulty understanding it because he hasn't yet realized what it is, and so the reader doesn't yet realize what it is.

SPURGEON: I could ask you questions about your historical work with Filipino comics all day, but I'll try to stick to a few. Can you describe why a historical interest in comics is important to you, or how it became important?

SPURGEON: I could ask you questions about your historical work with Filipino comics all day, but I'll try to stick to a few. Can you describe why a historical interest in comics is important to you, or how it became important?

ALANGUILAN:

ALANGUILAN: I had known there were a lot of really good Filipino comics artists who worked in the Philippines and abroad for many decades. I found out about this when I picked up the one and only issue of

The Philippine Comics Review in 1980. I was treated to this amazing gallery of work by the likes of

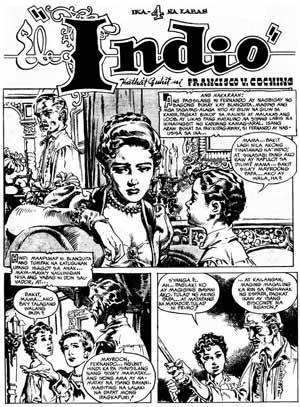

Francisco V. Coching,

Nestor Redondo, and

Alex Nino. It was that magazine that made me aware that the many artists I appreciated in the DC Comics I collected back in the mid 70's were actually Filipino, including my father in law,

Rudy Florese, whose work I was very impressed with on

Korak, Son of Tarzan.

That interest took a backseat when I rediscovered

Marvel Comics in the early '80s when I lost myself in things like the

X-men and

New Mutants. That interest made me think seriously about doing comics for a living and after many years, I eventually found myself working in it. I got to work on the

X-men and various other superhero titles as an inker for many years, retiring only in December 2005 to concentrate on my own work.

In addition to the many titles I inked for many Stateside comics, I was also active in the local Philippine comics scene, which in the early '90s was both depressing and invigorating. Depressing because the once great Philippine "Komiks" industry which was an indelible part of Philippine culture since the late 1920s when

Kenkoy by Tony Velasquez debuted, was slowly drawing to a close. Due to a variety of reasons beginning in the late '60s, Philippine comics slowly deteriorated, until at the very last late in 2005, the very last comic book from an industry that once published hundreds of different titles in a single month, was published.

The new breed of Philippine comics, which started to appear in the early '90s, owed very little in terms of content, style and format from those that came before. These were heavily influenced by Western and Japanese comics. Even then, I could recognize in my peers interesting individuality and originality.

That seems to have changed in recent years, when younger artists started to show me their work and I could see less originality and more literal parroting of foreign styles, specifically

manga. I voiced out my concerns many years ago and although I expected some argument, I wasn't prepared for the hostility that came with it.

In the course of my discussions with a lot of young artists, I reached back to reference the older Filipino artists whose work I knew about and shared it with them. Although they appreciated the work of these artists, most of them didn't know who they were. And it was a fact that really struck me.

In a way it was inevitable. Literally none of the thousands of comics published in the Philippines from the 1920s to the 1990s were ever reprinted or archived. There are no readily available books or magazines where one can read about them and see the art. There are no easily accessible public galleries or museums where one can see such art displayed.

For a country that have produced comics that appealed to the old and the young, where comics were never considered "just for kids," it's rather distressing to realize that comics were never considered "art." It never rose above the stigma of being considered as disposable entertainment for the masses. During its heyday, comics were widely read, but a few days later they ended up being used to wrap fish at the local market.

There was even a time that our Philippine National Library refused to give ISBNs and ISSNs to comic books because they believed comics had "no research value." Such is their contempt for comics that they would erroneously wield a universal publication ID system as means to deny or approve the legitimacy of a particular publication.

There is indignation in the local papers by columnists that a painter won the "Philippine National Artist" award, saying his award was meaningless because he won over "just a comic book artist".

For many years, thousands of original art were shredded by the publishers so they cannot be used again for other publications. Some artists have had to covertly steal their own art back to prevent them from being destroyed.

I was truly aghast upon learning many of these things, and it was then I resolved help in any way I can. I used up my savings to buy as many original art and vintage comic books as I can find, and then put them together for display in an online gallery.

The web site is only the start of the many projects I've resolved to pursue. The most immediate is the a restoration, collection and publication of

El Indio, Francisco V. Coching's classic 1952 comics-novel, representing again for the first time in many decades one of the best comics ever to be published in the Philippines. I've scheduled to release this early next year.

Another project is a

Philippine Comics Art coffee table book, which will collect some of the finest comic book art published in the Philippines, as well as a few pieces some of our best artists have done outside the country.

In the far future, I hope to muster enough funds to put together a real live museum to be located right here in San Pablo. I already have plans to build a mini-museum within the house I will be building for my family in the next few years.

All of this is being done to accomplish primarily two things: One is to reintroduce the work of our greatest illustrators to a younger generation of artists who are unaware of a great history and legacy in comics and desperately need a sense of personal identity as Filipinos.

Second, I hope to help uplift comics in the eyes of many Filipinos and to help convince them that comics is art, equally worthy of attention, exhibition, preservation and respect.

I consider this truly important because the body of work created by our artists in our "Golden Age," from the late '40s to the early '70s, is I believe one of the most remarkable and most unique in the world of comics. For a country so battered in the eyes of the international community, with a culture so malleable that it's greatly influenced with the arrival of every "next big thing," our Golden Age of comics is one of our shining moments. It's one of those things I can call truly ours and truly Filipino. It's something every Filipino citizen, artist or not, can take pride in.

SPURGEON: Is there a group of artists or an artist from the Philippines tradition that you feel closest to?

ALANGUILAN: There is a shortlist of artists whose work I find deeply inspiring.

1.

Francisco V. Coching

2.

Nestor Redondo

3.

Alex Nino

4.

Alfredo Alcala

5.

Rudy Florese

6.

Elpidio Torres

7.

Fred Carrillo

8.

Petronilo Z. Marcelo

9.

Fred Alcantara

10.

Larry Alcala

Collectively,they represent a whole spectrum of art styles from Coching's dyanmic figurework, to Redondo's graceful flowing brush strokes, to Nino's insane psychedelia, to Alfredo Alcala's intricate detail, and to Larry Alcala's funky cartooning.

SPURGEON: How many of your peers share your interest in history?

ALANGUILAN: Not too many, and some of them are writers more than artists. But thankfully, I like to believe I've had some effect on my peers as well as some of the younger artists who do acknowledge they were inspired the things they've seen on my site.

There are some, like

Lan Medina,

Roy Allan Martinez, and

Gilbert Monsanto, artists who are currently doing comics in the US, who were around long enough to have been able to work in the old industry and soak up the influences that have been handed down through the decades. You can still see a bit of the old Philippine style in their work.

SPURGEON: Unlike American histories, it seems like a lot of what you have on the Komikero.com site shows a comics publishing past that draws on larger traditions of magazine publishing and illustrating, not only specifically comics. Is that a difference between your comics tradition and the North American/European?

ALANGUILAN:

ALANGUILAN: Artists like Alfredo Alcala have openly admitted to have been very influenced by the likes of

Franklin Booth and

J.C. Leyendecker, and Alfredo, in turn, has influenced many other artists to seek inspiration in the great magazine illustrators and painters like

Frank Frazetta and

Norman Rockwell. At the same time, strong influence came by way of the great comic strip artists like

Hal Foster and

Alex Raymond. With the exception of Alex Nino, and a few others including

Ruben Yandoc (Rubeny) and

Jess Jodloman, the traditional Philippine style was classical and romantic, delineated by luscious and graceful brushwork.

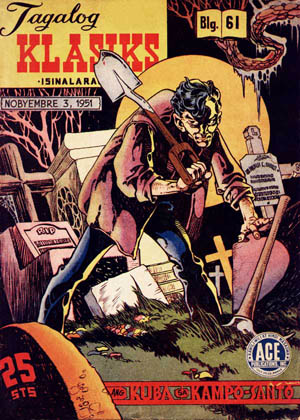

It's a style that the editors of the day probably didn't see fit to partner with superheroes, so a lot of those artists were assigned to do stories in the war, horror, western, and fantasy genres.

Even here in the Philippines, superheroes were few and far in between. Our most popular genres were romance, horror and humor, in an industry that offered comics of all kinds, from biography, fictional and non-fictional history, religion, travel, news and current events, agriculture, politics, myths and legends, poetry, crime and suspense, war, fantasy, and yes, even westerns.

After World War 2, people didn't have television and very little limited access to movie houses, specially to those living in the provinces. Comics then became the most popular form of entertainment and it was so because it appealed not just to children, but to the masses. The country is not a rich one, and most of our population hover below, in and around the poverty line. This was both fortunate and unfortunate. Fortunate because its mass popularity enabled comics to become an indelible part of Philippine pop culture. Unfortunate because the rich and elite, who pretty much decides what goes and what doesn't in the world of art, look down on comics as a cheap entertainment for the masses. It is a stigma that persists heavily to this day.

SPURGEON: Can you give me a snapshot on the comics "scene" where you are, any same-age peers you have and those younger particularly? What are they like? Where do they work? What kinds of comics are being done?

ALANGUILAN: As of this moment, the only remnant of the old industry is

Liwayway Magazine. Not even a comic book, it's a news, gossip, prose and poetry magazine with a comics section in it. It's only fitting that the magazine where the Philippine comics industry was born in 1929 to be still in publication today.

In the face of the falling industry in the early '90s, a lot of young artists, including myself, decided to create our own comics and publish them ourselves. By "publishing" it meant going to the photocopy place and have 100 copies made and have a sympathetic comics store carry them. Some had more money than others (or some had richer parents than ours) and they were able to afford to actually go and have 1000 copies printed at a real printing press.

The general output owes very little to the traditions of the old industry. These new comics were populated by mostly superheroes, with a few delving into fantasy and crime, with one or two doing very odd trippy flights of fancy. Very few attempted anthologies, opting instead for limited runs from one shots to four issues.

These comics were more expensive as the creators could not afford print runs that would assure an lower retail price. These are kids doing comics out of their own pockets after all.

This scene still holds true today, but some of us eventually established real publishing companies and some of the more popular and successful, like

Mango Comics,

Nautilus Comics, and

PSI Com publish comics on a more or less monthly basis. Much of their output is influenced by Japanese comics to varying degrees. Many other companies like Stephen Redondo's

Redondo KOMiX (Stephen is Nestor's nephew) and NEO Comics are very heavily influenced by Japanese comics as well. It's safe to say that manga has a very strong foothold in the culture of Philippine comics at the moment.

Some of us who have continued to self publish, eventually established our own personal legal and duly registered publishing companies. For my part, I thought it essential to do so because I've long decided that comics will be my career for all time so I better get off the underground and do this thing seriously.

Self publishers like

Arnold Arre and

Carlo Vergara have produced very popular and successful comic books that they have been taken on by established book publishers.

A Philippine convention for comics, called the

Komikon, is now in its 2nd year this October 21, and it's our opportunity to sell and promote our work and mingle with the other creators.

SPURGEON: There seems to be a social component to what you do, with meetings and get-togethers. How important has that aspect of meeting other artists been to you as a comics creator?

ALANGUILAN: Being a comics creator, I already live in isolation by default. Although I'm in touch with other people online, it's different when you have a gang of artists you can hang out with, share tips and techniques with, and just have a good time. I think living by oneself, even though I'm married, can have an adverse effect on your social skills, and I didn't want it to happen to me.

It's also great to see budding talents and help guide them do better work. It's also great because I myself learn a thing or two from other people. All in all it's been a very productive and enjoyable experience.

*****

*

cover to first issue of Elmer

*

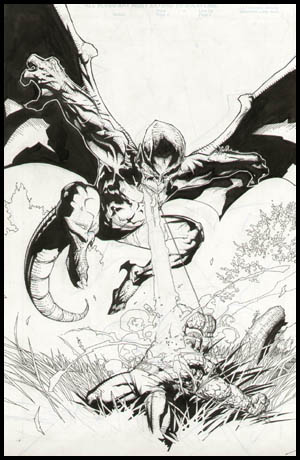

you might know Alanguilan as a popular inker for superhero comics like this one

*

panel from Elmer #2

*

the initial reveal from Elmer #1

*

a page of shifting perspectives from Elmer #2

*

a great Rudy Florese panel, from Alanguilan's site

*

a page from El Indio, from Alanguilan's site

*

an Alfredo Alcala cover, from Alanguilan's site

*

I like this panel from Elmer #2