Home > News Story and Obituary Archive

Home > News Story and Obituary Archive Obituary: Herb Gardner 1934-2003

posted October 30, 2003

Obituary: Herb Gardner 1934-2003

posted October 30, 2003

Herbert George (Herb) Gardner, the creator of

The Nebbishes cartoons and syndicated comic strip who went on to a long and distinguished career as a playwright, director and screenplay writer, died September 24 in his Manhattan home of complications due to lung disease. Although best known for his work on stage and screen, Gardner was at one time one of the nation's most promising and popular young cartoonists.

Gardner was born in Brooklyn on December 28, 1934. His father owned a tavern on the lower east side of Manhattan, on Canal Street, where Gardner spent many hours soaking up the atmosphere and listening to the men talk to one another. As a teenager he worked grunt jobs at the Cort Theater and National Theater, using his access to performances to watch repeated performances of plays that struck his interest. Gardner graduated from the High School for Performing Arts and attended the Carnegie Institute of Technology (now Carnegie Mellon University) and Antioch College.

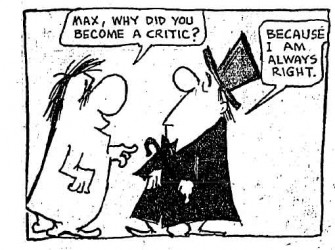

Taking a job with the Bliss Display Company to help defray the costs of school, Gardner later claimed to have used some spare time to make something for his own amusement: a decidedly non-cute doll that fell over. His employers were unimpressed, but Gardner began drawing a similar figure in his sketchbooks. In the mid-1950s, unable to find work in sculpture, Gardner found employment as a staff cartoonist at the New York Daily News. He was invited to draw cartoons for children on Shari Lewis's television show. These drawings were the prototypes for

The Nebbishes, which became a successful cartoon property and eventually a syndicated comic strip.

When most people remember

The Nebbishes, it's as a licensed property. "The Nebbishes were novelty items sold in stores long before they became syndicated," Gardner's longtime friend and fellow cartoonist and playwright Jules Feiffer told the Journal. "Back in the 1950s, they were really popular in New York, on things like napkins. Herb used to say there wasn't a surface in a home that couldn't be covered." The popularity of the Nebbishes was part of the growing influence of Jewish comedy in mainstream arenas in the 1950s. "Nebbish" is an adopted Yiddish word that at one time held a place in comedic vernacular now roughly reserved for "nerd," only lacking the latter word's suggestion of unpleasant or obsessive behavior. A Nebbish was usually endearingly out of place and always slightly helpless, an appealing figure that suggested alienation without embodying it. Gardner's cartoons help provided a bridge between Jewish stand-up comedians working the vaudeville circuit that called on such characters and a whole strain of mainstream American comedy from Jewish writers exemplified by the stand-up and early movies of Woody Allen. Gardner's most famous joke and oft-used template in merchandising was a portrait of two men slackly lounging in chairs, one saying to the other, "Next week we've GOT to get organized."

At the height of their popularity, The Nebbishes also enjoyed a short run as a syndicated newspaper strip, a stint that may have seemed longer than official records indicate due to the property's presence in the marketplace preceding its launch. That strip got its official start in the

Chicago Tribune and enjoyed its run in syndication beginning in 1959.

The Nebbishes was drawn in a loose but expressive gag-cartoon style, and appeared in somewhere between 60 and 75 papers. (Like all good historical sagas, there may even be a footnote: the strip was listed in

Editor and Publisher's annual round-up of available strips in 1982, a potential indicator of a brief yet unsuccessful revival attempt by someone with an interest in the property.)

The New York Times reported in its obituary for the artist and playwright that Gardner ended the strip in 1960.

Despite being told he was nuts for letting the profitable strip die, Gardner had his eye on other artistic outlets. He had written TV scripts for New York television starting in 1956. Simon and Schuster published his novel

A Piece of the Action in 1958. He also ached to write for the stage. Of his writing in general, he joked later that the increasing size of the strip's word balloons led him to believe that a change in careers might be necessary. Gardner enjoyed his first success on Broadway in 1962 with

A Thousand Clowns, the first of many plays that drew on the author's love for New Yorkers and their mix of melancholy and quirky charm.

A Thousand Clowns told the story of a children's television writer who quits his job for the sake of his sanity and battles for the adoption of his nephew. Critics heaped praise on its mix of wisecracks and pathos and the 27-year-old found himself the toast of the Great White Way. The Broadway run starred Jason Robards and the then-ubiquitous stage actress Sandy Dennis. After winning several theatrical awards, the play was made into a 1965 movie with Barbara Harris assuming the role of female lead. Gardner received an Academy Award nomination for best-adapted screenplay.

Flush with success and awards, cartooning had faded quickly and thoroughly from Gardner's professional life. Speaking of a man he described as a dear, close friend and as someone who shared the same influences and experiences, Feiffer explained to the

Journal that Gardner's passion for cartooning always seemed secondary to a host of other artistic interests. "Even before cartooning, writing was a big deal for Herb. He had won awards, and written a novel. Cartooning was the sideline that kind of took over when he found some quick success with it. He used

The Nebbishes to make a living. He began work on

A Thousand Clowns while he was doing

The Nebbishes.

The Nebbishes was in a sense his job. Once he opened the play, and the play was a big success, I think the other work disappeared."

There was plenty to take its place. Gardner efforts that made it onto Broadway due to the momentum caused by

A Thousand Clowns were

The Goodbye People in 1968, and

Thieves in 1974. Highly anticipated,

The Goodbye People marked Milton Berle's return to the New York stage after 25 years. He played Max, an older man prescribed bed rest who wishes instead to revive his hot dog stand on Coney Island in the dead of winter. Flush with success on both coasts, Gardner both wrote and directed the play. Playing only seven episodes before closing, it was one of the decade's more notorious flops. Thieves was a modest success after a tumultuous preview process in which the lead actress quit, and in 1977 became a movie with the stage show's stand-in savior Marlo Thomas reprising her role as the lead and Gardner providing the screenplay. In 1980, the musical

One Night Stand closed in previews; Gardner had provided the lyrics and book.

In 1984, Gardner made his film directorial debut with a movie version of

The Goodbye People, starring Judd Hirsch. This was fortunate casting, as Hirsch would become the primary interpreter of Gardner's later-period work, and the most successful actor in Gardner roles.

Gardner finally re-entered the first ranks of popular American Theater with the audience pleaser and box office juggernaut

I'm Not Rappaport, about two elderly men, one Jewish and one Black, who meet in Central Park. In its best-received version, the play starred Hirsch and Cleavon Little. Despite uneven critical notices, it won the Best Play Tony Award in 1986 and Hirsch won for Best Actor. The play ran for over two years. Walter Matthau and Ossie Davis would latter assume the roles in a film written and directed by Gardner.

Conversations with My Father debuted in 1992, and featured a more critically lauded script and another Tony Award-winning performance from Judd Hirsch.

Conversations was largely autobiographical.

In addition to adapting his own work for the movies, Gardner produced and wrote the screenplay for the 1971 Dustin Hoffman film

Who is Harry Kellerman and Why Is He Saying All Those Terrible Things About Me? The script was an adaptation of one of Gardner's own short stories. According to an appreciation written by Mark Evanier for his

News From Me on-line commentary site, Gardner was rumored to have been involved in several movies as an unofficial writer brought in to improve comedic moments; one film it was said he worked on is

All That Jazz. The director and subject of that film, Bob Fosse, made a cameo appearance in Gardner's

Thieves. This kind of organic working relationship over more than one project was familiar to Gardner. For instance, he was one of the friends in "Marlo Thomas and Friends" that provided stories for the cross-media children's production and '70s pop culture keystone

Free to Be You and Me. It appeared on TV three years before Thomas would star in Gardner's

Thieves film and at roughly the same time she stepped into the stage version.

In 2000, Gardner received the Lifetime Achievement Award from the Writer's Guild of America. His work remained of interest to producers. Gardner's highest profile plays enjoyed revival interest on Broadway in recent years yet met little success. A big budget version of

A Thousand Clowns starring Tom Selleck ran in 2001 and flopped despite the cavalcade of publicity the actor's appearance brought the production. Judd Hirsch reprised his role in

I'm Not Rappaport, this time opposite Ben Vereen, in 2002. This run also failed to meet expectations, but the interest in and anticipation for the production indicated a long and healthy life for the playwright's best works.

Herb Gardner's three most successful plays,

A Thousand Clowns,

I'm Not Rappaport, and

Conversations With My Father, continue to be performed in theaters around the world with no sign of stopping anytime soon.

Nebbishes items pop up on auction web sites just as consistently but with much less fanfare, clever totems from Gardner's road not taken and a very specific time in American comedy.

From his hard-won place as one of the most popular American playwrights of the last forty years, Gardner appeared to look back on his days as a cartoonist with genteel bemusement. "It still seems odd," he told

Newsday in 1996. "I never thought I'd be fad."

Herb Gardner is survived by a wife, Barbara Sproul, and two sons, Jake and Rafferty. A first marriage, to Rita Gardner, ended in divorce.

Originally published in The Comics Journal #258