Home > Commentary and Features

Home > Commentary and Features So Why Were The X-Men Popular?

posted June 26, 2008

So Why Were The X-Men Popular?

posted June 26, 2008

Tucker Stone

Tucker Stone's live blogging of the

Uncanny X-Men Omnibus Vol. One a few weeks ago (

one,

two,

three,

four,

five,

six) is quite the achievement: smart where it needs to be, stupid where it can be, and funny throughout. I recommend it. It's a compelling view of some well-regarded comics that few people have taken the time to go back and explore.

A question I received from a couple of people who read Stone's exegesis was this: why were those comics popular in the first place? Trust me, they were. The initial burst of "All-New, All-Different"

X-Men comics has to be considered a supremely successful run by almost any standard, a groundbreaking effort that echoes in current superhero comics the way that some element of

Star Wars reveals itself in nearly every summer movie blockbuster. It's the dividing line between major eras at Marvel, and the first franchise-sustaining success of the post-Lee heavy involvement era (following two potent but ultimately more limited hits:

Conan and

Howard the Duck). Two successful mainstream comics writers,

Grant Morrison and

Joss Whedon, turned high-profile runs on the X-Men franchise into flat-out tributes to that original run of issues. Their influence can be seen throughout the sub-genre, and the book itself spun off into any number of re-launches, supplemental titles and mini-series. I talked about one aspect of what made those comics popular on one of Stone's comments threads. I thought I might repeat some of those points here, and add to them.

First of all, it should be remembered that the Len Wein/Chris Claremont/Dave Cockrum/John Byrne

X-Men, a core run that I place from

Giant-Size X-Men #1 (1975) to

X-Men #143 (1981), wasn't as far as I know a runaway sales success or industry pacesetter as it was an extremely well-liked superhero comic with a lot of influential, hardcore fans. It was the buzz superhero book of the late 1970s, the same way that

The Dark Knight Returns,

Watchmen,

JLA,

The Authority, and

Daredevil (under Miller, then Bendis) would play that same role at later points in time. Its best issues and storylines had an impact on the direction of superhero comics that

outpaced its actual sales numbers. Domination of the sales charts came later, on comics with this run of comics as its informative foundation.

Even within that original burst of issues,

X-Men did not become a comic of passionate interest to devoted comics readers -- at least those of my acquaintance -- until about issue #125 or so. By then the comic's content began to ramp up into a sustained action-adventure narrative. At the same time, the title's back issues began to receive attention. It was hard for kids to ignore that

X-Men #94, a comic they may have purchased just three or four years earlier, was selling for $15-$20. While the title picked up adherents throughout that foundational run, my memory is that it wasn't until the last year and a half's work by the Claremont/Byrne team that the title began to be widely recognized as something special.

Second, you have to remember the historical context in which these comics appeared. It felt to a lot of comics readers in the mid- to late-1970s that superheroes were so dominant as a genre that it was only right to see

the entire medium in terms of accomplishments within such stories. This was a combination of legitimately-won impressions as to where the market was headed and how superhero fans, now a generation deep into organized fandom and

Stan Lee's flattery, chose to view their genre of choice: worshipfully and myopically. This was a total lie on many levels, of course. There were plenty of non-superhero comics that continued to sell well and other comics that were of surpassing quality published during that time period. But if you were a superhero reader in the mid- to late-1970s, it felt like you were reading the one place where comics was going to live or die; other genres didn't matter the same way. Superhero comics dominated the imagination of hardcore readers. When those readers chose to muse on the future of the form, or its legitimacy as an art form, they thought in terms of superhero comics. As the best superhero comic going,

X-Men was viewed with much greater importance than it would be now.

Seen in a superhero-centric light,

X-Men was a strange little comic in a lot of ways, none more so than in how it was differently paced than the vast majority of its peers. It was the most laid-back action-adventure comic book, maybe ever. When your entire comics reading world was superheroes, any comic that threw its spotlight on the personal interaction of team members seemed like it was getting at the real sauce far more than, say, what

Jack Kirby was doing at that point with his aggressive, dynamic style. Fans used to say things out loud like, "I love those scenes where you just get to know the characters, where they just sit around and talk."

X-Men had more of those scenes than any other comic. They may have been rudimentary moments, characters brooding over some element of their personalities in a convenient, summary, almost declarative fashion. In the case of Nightcrawler taking a quiet moment in the woods to freak out a bit about a fallen teammate, they could be human (if emotionally florid) moments. In the case of Storm's tendency to walk around naked or near-naked, or Wolverine's declaration that he would "get" Jean Grey, these reveries could make for semi-disturbing moments. In the case of a hypnotized Colossus whipping out a pair of coveralls and a Russian cap and becoming a Soviet Superhero as a way of dealing with guilt over abandonment of his home country, they could be stupid moments. No matter how such moments were expressed, the deliberate pacing and attention to character set against a backdrop of more standard superhero storytelling distinguished the book from most of what had come before.

Third,

X-Men brought solid basics of execution to the table. (And yes, this probably should have come earlier.) We often forget in evaluating comics how important storytelling fundamentals can be -- part of this is that saying "they were really well-done comics" doesn't secure anyone a position generating concepts for movie studios, and part of it is lingering self-hatred when it comes to the medium itself.

X-Men worked. The new X-Men characters were well-designed (the Nightcrawler character in particular), the characters were easy to tell apart and just different enough that a kid could seize on their personalities fairly quickly, and they had weird adventures that in the first couple of years plugged into that era's pre-occupation with space opera. Both

Dave Cockrum and

John Byrne made appealing comics art, while

Chris Claremont was probably the most talented acolyte of the

Don McGregor Church of Excessive Exposition. It was nice for a lot of kids to have a brand-new bunch of well-done superheroes to fire the imagination in a pre-TPB era when figuring out the backstory for a lot of Marvel's characters seemed daunting. When

X-Men began to hit, you could buy about 20 comic books and have the whole saga to date. It was sturdy entertainment, and an appealing choice for one's hard-earned allowance money.

Fourth,

X-Men worked as sly commentary on the superhero genre. Unlike the more established superheroes of the Marvel Universe with their displayed competence and regular routines -- even Spider-Man at this point was dating a lot and working full-time in Manhattan -- the X-Men basically ran around the world willy-nilly getting their asses kicked and running away from fights. Heck, they nearly got their hats handed to them by

Moses Magnum. The dislocation that resulted gave the book a non-traditional feel that was more like an "every week a different setting" TV show. Because most fans had yet to project onto the X-Men characters their own feelings of self-worth, Cyclops and the gang could lose a lot of fights and eke out meager victories in a way that felt more "real" to readers without upsetting them. Within the story, it gave the team an appealing, scrappy quality that was one of the under-appreciated creative successes of the original run. They were like a college basketball team from the Mountain West going deep into the NCAA tournament. They'd play ball with anyone, and always enter the last minute with a chance to win.

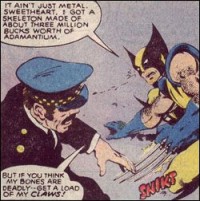

This brand of genre commentary was probably best realized in a scene at the end of #132 where Wolverine decides he's going to kill everyone. If you're near my age, I bet you even know the panel:

This qualifies as a gutsy statement instead of a routine one or even a macho one, and is therefore that much more appealing. When Wolverine uttered his promise, the entire team had just been jacked up by a not very inspired riff on one of John Steed and Emma Peel's old villains,

the Hellfire Club. Wolverine himself had been disposed of by

a super-powered Sebastian Cabot. Wolverine talking smack was a cool moment not because Canada's greatest export routinely ran around killing everyone and making them know that he's the best at what he does -- the way he might now -- but because at the time Wolverine wasn't a sure thing in the normal superhero context available to him from month to month in those pre-Mature Readers days. He cut open his fair share of robots, but he also got punched off of a planet and lost a fight to Sasquatch in two panels. Watching him make good on this promise seemed like it would be an exciting thing, not a sure thing.

This kind of subtle difference in the way the superhero formula was realized was important for readers that devoured comic book after comic book every single week. You felt less jerked around or pandered to in

X-Men than in those books where successful outcomes that flattered the superheroes involved seemed pre-ordained. Jack Kirby actually took overt steps towards this kind of genre correction with the

New Gods material, but the X-Men books seamlessly made reduced expectations part of the formula. Like

Steve Austin and

Muhammad Ali, the X-Men

lost their most famous battle, but became more popular for it.

Fifth, as hinted above, Wolverine killed people. Or at least you figured he had, and he might again soon. Wolverine's break-out status can't be underestimated as a part of the title's appeal. It was a rallying point between fans and an easy way to communicate your enthusiasm for the work. "You have to see this guy," I told a lot of people at summer camp, as I dispensed my

X-Men comics during Rest Hour. "This guy is cool; he's not like other superheroes." While I suppose some people reacted to the noble warrior elements or the more soap opera aspects of the character, or maybe just liked him as a pugnacious underdog who cocked off to the dreary tight-ass Cyclops, for most people Wolverine's proclivity towards excessive violence is what distinguished the character. At least it's what registered with my comics-reading pals. That violence was particularly powerful in the context of the time. Living in an era before cinematic video games and easy-to-rent John Woo movies, kids in the late '70s were fed a lot of sanitized reading and gutted entertainment material. For instance, the favorite Saturday morning cartoon of a lot of boys my age was a Tarzan adventure serial where the most violence you got to see was Tarzan jumping over a pit of some sort or running somewhere or maybe riding an elephant. But you watched. You hoped. And when Marvel made any sort of nod towards real-world violence as an option in its sanitized world, you flipped out it was so welcome.

It was particularly frustrating in comics because the new generation of fan-writers tended to emphasize an increased, supposed "realism" in these stories… except, in many cases, where violence was concerned. It made perfect sense that if you were a superhero, and you had giant metal claws, that you might run around gutting a few monsters and, eventually, human-folk. Kids of a certain age are all about their entertainment making sense and meeting those kinds of expectations, and kids that continued to read comics past a certain age wanted to be able to point at something more graphic and seemingly mature than Green Lantern making a giant catcher's mitt and scooping everyone up to take them to space jail.

The creators supported Wolverine with a necessary (there were only 20 or so pages a month and a lot of characters to get in) and smart approach to the character that depended on restraint. Unlike every popular superhero that came before him, Wolverine had been around for several issues without ever meriting a proper secret origin. The creators smartly declined to give him one. This made kids lean in to pay close attention to any clues as to the full extent of Wolverine's personality and background (he reads Japanese! his name is Logan!), and the origins they wrote in their heads were likely ten times more satisfying than what Marvel would eventually make explicit. I know mine was. There aren't a whole lot of four-color creations that live the "less is more" motto, but Wolverine was definitely one of them. Plus, you know, he killed people. Or could have. Any second now.

I think that's most of it. There are other strong points to those comics.

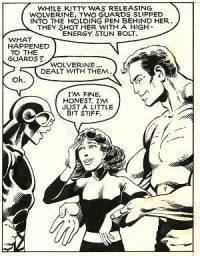

Kitty Pryde is a fun character, and another one that serves as overt commentary on the direction of superhero comics at the time. Also, she's an inch deep and a mile wide. You pretty much get everything that's valuable about her in two or three pages -- her fannish nature, her real-girl qualities in a world of spandex-wearing models, her secret girlfriend approachability for a lot of young males, her admirable intelligence, and her embodiment of an older formula that hadn't been exploited by the X-Men for a while, that of the frightened, exhilarated outsider/newcomer (Noah Wylie would play the Kitty Pryde role on the TV show

ER) -- which meant she made her impression almost right after being introduced. Claremont and Byrne each in their plot contributions seized on the effectiveness of emphasizing story moments even at the expense of a better-flowing narrative, a way of approaching superhero comics that Mark Waid and Grant Morrison would eventually nail and make the industry standard. I might not be able to tell you in exactly what adventure each moment took place, but I remember the first time when you realize Wolverine was popping the claws out of his arms, when that same character burst out of chains at some circus sideshow, when Professor X confronted Phoenix, when a big silhouette of

Jason Wyngarde/Mastermind appeared behind the character, Nightcrawler teleporting with another person for the first time, Storm trying to pick the locks when the X-Men were trapped like infants, and so on. One thing that's forgotten is that many of the stories were cut with an appealing silliness that looks better today than it did even back then, like

Arcade, The World's Least Cost-Efficient Assassin, or as Stone noticed, Magneto

dressing a robot in a maid outfit.

So

X-Men was solid comic book entertainment that distinguished itself against the comic books of the time in several savvy ways that caught the attention of longtime, hardcore fans, the same kind of fans that were almost certain to look past lot of the title's more obvious failings (its nonsensical plots, its over-flowery language, its creepy undertones) and a group of people that would likely foster the next generation of creators. It hit in the right way at the right time with the right people, and soon launched itself into the sales stratosphere and took a lot of books with it.

One thing I'm pretty sure

wasn'ta factor in the success of the late-'70s

X-Men was the series' supposed strength as a metaphor for race-oriented bigotry, which always struck me as strained if not outright dumb-assed. It just doesn't make any sense. On the level a superhero comic could embody inclusive values, those issues had been fought and won in popular culture for more than a decade before the

X-Men re-launched. Even something as watered down, formulaic and ineffectual as art as

The Jeffersons could be more to the point than

X-Men on race. Also, as many have pointed out, being of a certain race isn't the same thing as being allowed to shoot ray beams out of your eyes, and the differences are more important than the similarities. A sexual orientation metaphor works better than race, but only slightly, and even then I think that's something that was about eight to ten years away from finding routine expression in the comics. An internationalist point of view never quite coalesces into anything and seems to fade over time.

If there was a metaphorical undertone to these

X-Men comics, it was probably in fan self-identity. The New X-men were older and much more confident of their place in the world than the earlier team. So were the second generation of Marvel Comics readers. The original X-Men wanted to assimilate, while these X-Men wanted to be awesome and be appreciated for their awesomeness, and barring that left alone, much like older fans were less and less interested in anything other than the items of their preoccupation, and were suspicious of selling out, compromising, and giving in to a herd mentality. It's as that idea took hold with young people that the title's popularity grew, not the issues of bias, race and/or sex. Plus, you know: solid comic book.

*****

"Arcade, the World's Least Cost-Efficient Assassin" is swiped from Gil Roth

Addendum: The great Steven Grant writes in to say, "As far as I recall, from about the 'Hellfire Club' episodes of UNCANNY X-MEN on, it was Marvel's best-selling book, as a rule. The Claremont-Byrne run was incredibly popular, once it got going." I didn't think it ascended to Marvel's top book until a few years later, although it's worth noting the Hellfire Club sequence was the last year of the run we're talking about.