Home > CR Reviews

Home > CR Reviews Cecil and Jordan in New York: Stories by Gabrielle Bell

posted April 20, 2009

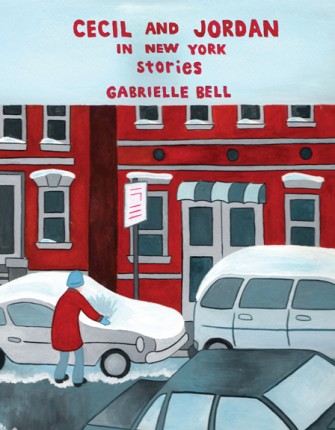

Cecil and Jordan in New York: Stories by Gabrielle Bell

posted April 20, 2009

Creator: Cecil and Jordan in New York: Stories by Gabrielle Bell

Publishing Information:

Creator: Cecil and Jordan in New York: Stories by Gabrielle Bell

Publishing Information: Drawn and Quarterly, hardcover, March 2009, 152 pages, $19.95

Ordering Numbers: 9781897299579 (ISBN13)

It's fun to take a step back now that we're a decade or so into comics more-concerted push into film as a feeder art form and take a summary look at the medium's current influence with cinema. Unsurprisingly, comics in film sort of looks like comics itself. For far too many people, comics in the movies means superhero comics in the movies. In that arena, Marvel seems to be pressing forward with DC following, with Batman being the sole exception. No on really knows what to do with Wonder Woman. There seems to be an unconscious effort by multiple actors to get fans on board with each and every company 's pressing need to make money, no matter how this might work out -- or not -- for individual creators. Scattered success stories elsewhere are largely ignored, even when they're artistically fruitful. The end result is that comics seems a long way from having the more complex relationship to the film industry that prose and theater enjoy: an open-ended relationship that involves mining characters and properties to a certain extent but also allows room for bringing potentially useful voices into the creative fold.

Of all the cartoonists and comics creators with an opportunity to make that sort of impression in television and film in the years ahead, one of the most compelling is Gabrielle Bell. Bell's four-page "Cecil and Jordan In New York" has been adapted by Bell and director Michel Gondry into Gondry's segment of the omnibus film

Tokyo!, which began a run in the art house circuit last month. A lot of press was done in support of the movie, Bell was involved, and the extent of her creative contribution sounds significant. She not only worked on the adaptation but, drawing on information made in various asides, looked at locations, assisted in casting and was a presence in the director's ear during filming. This is interesting in that Bell's strengths as a young cartoonist tend to be revealed in smaller, more immediate choices on the page. The specificity of detail in Bell's stories may help makes them universal. Their conceptual strength may help make them appealing. But it's the specificity of her creative choices on the page that helps make her formidable.

A new collection of Bell's comic work,

Cecil and Jordan in New York: Stories By Gabrielle Bell, also arrived this Spring. It contains the title story adapted for the short film and features more of her earliest short-story comics than it seems to the looser, autobiographical work by which she made her initial impression in comics circle. Included is a story that on reflection was almost certainly informed on some level by the beginnings of a relationship Bell enjoyed with Gondry. It may be the ambition and reach on display, but something about the collection feels more open and engaging than the stories did when they appeared individually, or in other efforts to bring Bell's work to a wider audience. Patterns begin to emerge.

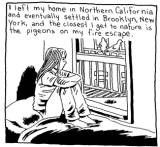

There are a variety of gradations in narrative tone throughout the collection. This matches several tweaks in visual approach, slight variations story to story, particularly when it comes to how the cartoonist employs shading but also in how the staging of her figures. As handsomely designed as just about anything D&Q does these days, this grouping of Bell's comics has been rightly lauded for their tone, their attention to emotional nuance and for the snapshot they provide of urban isolation leavened by moments of strangeness. My primary interest, however, is that they're executed in a resoundingly professional and even occasionally thrilling manner. A second look at the material provided by this new volume suggests a cartoonist whose specific artistic choices testify to a more restless creativity than communicated in paeans stressing age and outlook and shared experience. There's a genuine, idiosyncratic artistic sensibility at work that animates the material past the cartoonist's initial choices. Like the best comics, it's hard to boil the work down, difficult to summarize why it works. Bell does things that surprise the reader. Several such moments exist throughout this book, focusing and perhaps even diverting slightly the more concerted flow of the main narrative of which they're a part.

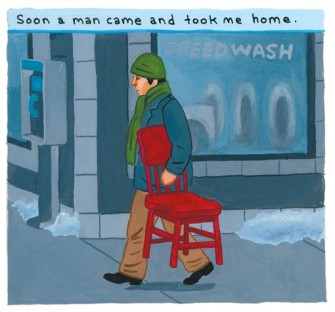

* in "Cecil and Jordan in New York," the story of a girl that becomes a chair is supported by a color palette that brightens as Cecil finds satisfaction in her new life as a chair. Colors further suggest relationships character to character, and who is an amenable partner for whom. This is crucial because of how late in the narrative the transformation takes place, which shifts the onus from the practical details of that occurrence and into their more general meaning in the course of Cecil's life.

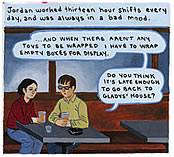

* in "I Feel Nothing," there's an impressive sequence where the protagonist thinks through the implications of a decision regarding a neighbor. This is shocking because it's a complete reversal of the narrative's focus to that point. Bell then underlines this shift by depicting the actual run of events that follow the protagonist's decision far past the point where many authors might have ended their story.

* the dance of physical proximity on a sofa that concludes "Year of the Arowana" is one of the showier set pieces in the collection, but on a second look it's a compelling blend of body language and post-dated narration that works against what you're seeing. The way Bell teases the last line into the situation means we end on uncertainty that challenges everything we've seen so far.

* in an adaptation of Kate Chopin's "The Story Of An Hour" called "One Afternoon," Bell digs into that story's most famous moment (the main character feels free when she learns of her husband's death) through a one-page sequence where the protagonist tosses and turns in a way that subtly suggests a change in physical perspective regarding ordinary circumstances that mirrors the emotional awakening. Played with less subtlety, the entire story might have been capsized. Then, as is the case with "I Feel Nothing," Bell repeats the effect in a more standard reverie on the page following in way that serves to heighten the effect of the key passage.

* in "Felix," the active plot progression is supported by several near-hypnotic -- and by some cartoonists' professed outlooks completely unnecessary -- sequences in which the title character moves from one place to another, gearing himself up for whatever encounter is about to take place, stepping outside of himself in a way that proximity to others seems to rarely allow. What other cartoonists might have skipped over altogether become a crucial window into understanding how he and his tutor relate to one another, and how he sees the world in a broader fashion.

* shifting perspectives dominate "My Affliction," including a few where we look right at the character and I think only one where we see the dreamlike story unfold from her perspective. The shifts underline the humor at the length and elaborate ridiculousness of the dream story, the emotional up and downs detailed and almost embarrassing incidental detail brought to bear.

* in "Summer Camp," one of the collection's more universally evocative stories, our lead briefly runs away to a summer camp after latching onto the positives of last summer's experience and comparing them to the misery of school. The fact that summer camp is still out there somewhere, and the thought it might offer some of the same comforts year-round that it does for a few days between grades, is something that has to have occurred to a lot of children. Bell's depiction of the dissolute-looking physical plant and the events that follow is practically festooned with sublime, minor-key touches. Two of the best are the oddly powerful and specific way Bell describes her character's semi-epiphany during the time she spent there, and the humorous glaring and grumbling in which she engages when the adults that locate her don't take her directly home.

In a popular culture dominated in many ways by film and from within a medium whose industry seems even more merrily dominated than most, it's exciting to watch someone who might have those opportunities that's fully engaged in the creative process, someone whose work with smaller moments is as important to the final result as something you could bring into a pitch meeting. Gabrielle Bell's comics don't

just offer an interesting character, or central idea, or even a unique texture (something about comics' contribution to film that's also underrated). Bell's best comics are well executed, too, sometimes oddly so, and nearly always her choices bring to the reader a stronger overall artistic experience. That's a rare gift, and it's one that as a comics reader I don't mind sharing with as many media as Bell would care to explore.